Bennito L. Kelty

Audio By Carbonatix

During his visit to Aurora on October 11, former president Donald Trump promised to start Operation Aurora, a mass deportation project, on his first day back in office, and in the two weeks since he was re-elected, Trump has doubled down on that vow.

“We will send elite squads of ICE, Border Patrol and federal law enforcement officers to hunt down, arrest and deport every last illegal alien gang member until there is not a single one left in this country,” Trump said at the rally at the Gaylord Rockies Resort. “And if they come back into our country, they will be told it is an automatic ten-year sentence in jail with no possibility of parole.”

On November 18, Trump posted on his Truth Social platform that he’ll use an emergency declaration to bring in military support to carry out Operation Aurora’s mass deportations. And he’s appointing the staff to back that up: Stephen Miller, who spoke in Aurora, has been nominated for deputy chief of policy, and former ICE agent Tom Homan will be “Border Czar.”

As they look for clarity regarding their situation, migrants in the area have turned to the Aurora Migrant Response Network, the group that’s been leading the local response to the influx of migrants during the past two years. Despite the uncertainty, the MRN says it’s seeing a surprising level of calm among migrants, but notes that many are definitely anxious about what Trump’s Operation Aurora will do.

Mateos Alvarez, head of the MRN, says that immigrants in Aurora are “nervous” about Trump’s promises of mass deportations, particularly if they’re recent arrivals in this country.

“For those who have been here a while…this is another election cycle, and they are hopeful that they can stay focused on finding work, raising their families and being productive citizens,” Alvarez says. “At the same time, for many who are waiting for hearings and that type of thing, they’re thinking, ‘If I get deported, my life is in danger.’ It’s an interesting contrast.”

Chris Gattegno, executive director of Aurora Community Connection, a member of the MRN that offers educational and health-care resources to immigrants, says that he’s scheduled immigration attorneys to “have open sessions with the community where they can ask their questions and hopefully get answers that give them clarity, which is sorely lacking.”

Aurora’s immigrant community is “imagining that even with a green card they’ll get deported,” adds Gattegno. “People think that they’re going to be put on the plane within one day. There’s just so many iterations of how people feel right now.”

Alvarez agrees that immigrants seem to be “bracing themselves emotionally, but they rely on entities like the Migrant Response Network for information or guidance.”

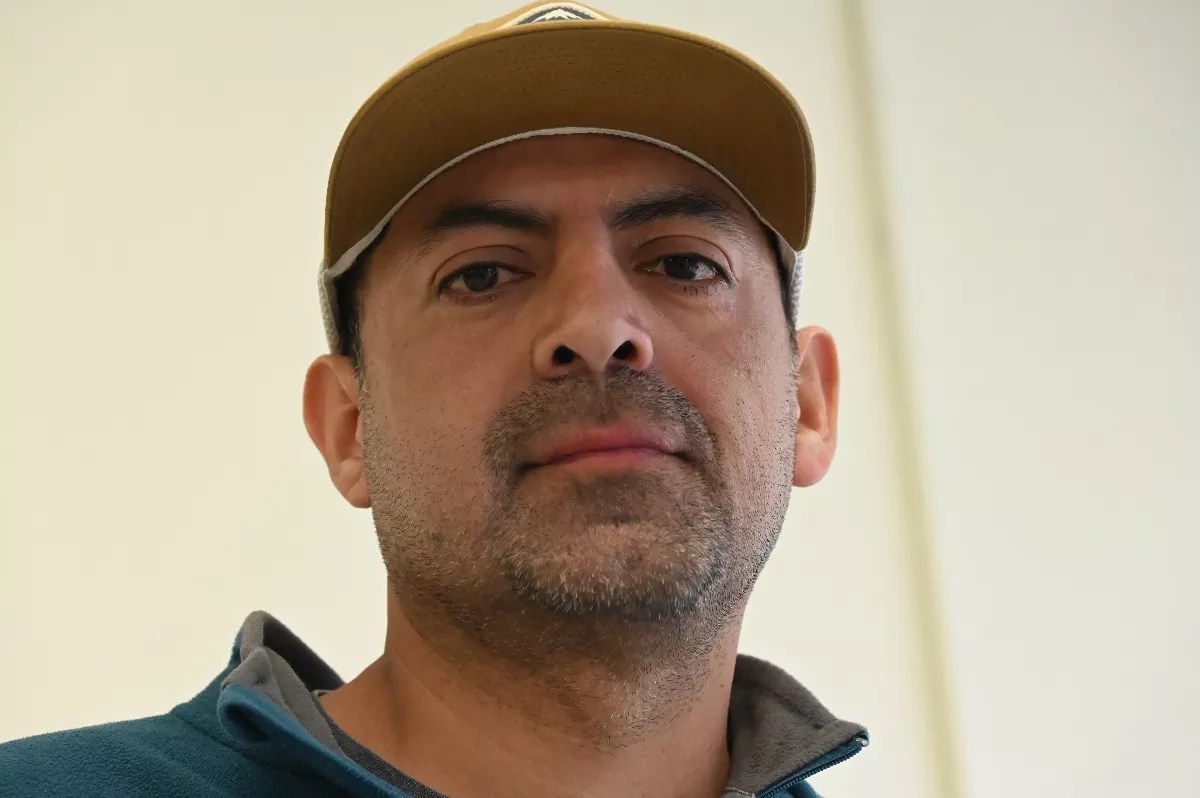

Mateos Alvarez leads both the Denver Day Labor Center and the Aurora Migrant Response Network.

Bennito L. Kelty

Colorado’s third-largest and most diverse city caught Trump’s attention after national headlines reported a takeover of Aurora apartments by the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua. The Aurora Police Department and Mayor Mike Coffman have disputed that account, saying it was invented to cover up neglect by out-of-state slumlords.

About 43,000 migrants have come to Denver during the past two years, mostly from Venezuela; about half of them are still believed to be somewhere in the metro area, according to the Denver mayor’s office. As many of those migrants made their way to jurisdictions neighboring Denver, nonprofits joined together in the Aurora Migrant Response Network. About fifty nonprofits now belong to the MRN, and all of them have been working with migrants, refugees and undocumented immigrants in Denver and Aurora for years.

Right now the group is trying to think of Operation Aurora “in a pragmatic and practical way,” says Alvarez, who also runs the Dayton Day Labor Center. Its members are focused “on figuring what’s real from rumor, and prepare for that and not get caught up in the emotional drama or what could happen,” he adds.

“We’re really trying to be as focused as we can to address what’s before us that’s real,” Alvarez says. “Right now, it’s almost like a slogan: What does Operation Aurora actually mean? And from what I understand, broadly it means they’re going to deport people.”

MRN doesn’t yet know what form Operation Aurora and the mass deportations will take. “What’s legal? How can he do that? And at what levels?” Alvarez asks.

Gattegno is drafting a letter to members of the migrant community, telling them that ACC is “here for them to give them information, to give them facts.” He says he’ll stress to them that “you need to carry your papers with you. You need to literally have a copy of your passport or your green card. Hope for the best, prepare for the worst – and in this case, the worst is being detained erroneously.”

For members of the MRN, questions also loom about funding. The City of Aurora passed a resolution in October to investigate which nonprofits had received money to move migrants into the city, which the MRN felt painted a target on its back. Gattegno believes the Trump administration will do something similar at the federal level, and he’s expecting to lose funding.

Chris Gattegno, the executive director of Aurora Community Connection, says he’s telling migrants in Aurora to carry around what documentation they have.

Bennito L. Kelty

“The effect of the Trump administration may not be immediate, at least when it comes to funding,” he says. “But I do believe that come 2026 or even late 2025, the support from the federal level is going to dry out.”

Without federal funding, nonprofits supporting migrants will look to private foundations, “and frankly, this year was already a hard year for most nonprofits because there was so much competition and so little funding available,” Gattegno says. “It’s only going to get worse.”

Alvarez opened the Dayton Day Labor Center in 2016, at the start of the first Trump administration. During the next four years, he says finding work for immigrant day laborers was easy, which he credits to the lingering success of former president Barack Obama.

“There was more work than there were workers back then,” he adds. “And then COVID hit. The economy changed. COVID made it tough. That’s when things changed and never went back to being like it was.”

In October 2022, Alvarez pulled up to the Dayton Day Labor Center one morning and saw “both sides of the street full of new faces and new migrants.” That’s when the influx of migrants started for him – two months before Denver declared a state of emergency in December 2022.

“Now there’s way too many workers and not enough work,” Alvarez says. “We’re struggling on that end, and that’s what we’re trying to address and change.”