Bennito L. Kelty

Audio By Carbonatix

Nonprofit organizations in Aurora that have responded to the influx of migrants during the past two years are concerned about a new city council resolution seeking to “investigate” their work with Denver.

On Monday, October 14, Aurora City Council voted 6-2 in favor of directing the city manager to “investigate whether or not the State of Colorado and the City and County of Denver have placed immigrants in Aurora,” and to “prepare a list of community organizations that have received funding specifically dedicated to aid immigrants,” according to the resolution.

“The people of Aurora have the right to know,” said the proposal’s sponsor, Danielle Jurinsky. “We’ve heard about the nonprofits that received all of this funding, American taxpayer dollars, to move these people here.”

Jurinsky has been riled up about immigration for months; she’s spread the claim that Venezuelan gangs took over apartments and even expanded on it at the Trump rally in Aurora on October 11. While the Aurora Police Department and Mayor Mike Coffman deny that gangs control any buildings, Jurinsky has proclaimed herself Aurora’s “loudest voice” in insisting that violent Venezuelan migrants are the city’s top issue.

The point of the resolution is to find out how migrants got to Aurora, Jurinsky told her colleagues, adding that residents deserve to know “how much money went towards it, what the state’s involvement was, what the City of Denver’s involvement was. People have the right to know exactly what happened in this city.” She didn’t suggest what the City of Aurora should do with its findings.

For his part, Coffman told the council, “We just need to retrace our steps.” In particular, he wants to find out how migrants ended up in the CBZ Management properties that are at the center of the gang rumors and “make sure it never happens again,” he said.

“We don’t know how many people were moved into the City of Aurora; we don’t know what benefits they received,” he added. “We do know that oftentimes they can’t apply for a work permit unless they’re here for 150 days, so we need to understand what was done.”

A Quality Inn in Aurora was converted into a migrant shelter by Denver in December.

Bennito L. Kelty

In a statement responding to Aurora’s resolution, a spokesperson for Mayor Mike Johnston defended Denver’s work with nonprofits to handle the influx of migrants.

“Denver took what many saw as a crisis and turned it into opportunity by partnering with nonprofits to help thousands of newcomers find stability, contribute to our economy, and have the opportunity to chase the American dream,” the statement reads. “We stand proudly with our immigrant community and with our nonprofit partners, whose dedication and life-saving work should be applauded, not demonized.”

In December 2022, the City of Denver declared an emergency as hundreds of migrants, mostly from Venezuela, started showing up by the busload from Texas; since then, the city has tallied the arrival of 43,000 migrants. The mayor’s office estimates that about half of them stayed in the metro area, but it doesn’t track where new arrivals end up.

“Had we turned our back, there is little doubt that many of the 43,000 people who arrived in Denver over the last two years would today be sleeping on the streets rather than in their own beds,” the mayor’s office says.

Many migrants, especially West Africans, went to Aurora and other surrounding areas. While Aurora doesn’t keep a count of migrants who come to the city, Mateos Alvarez, who runs the Dayton Day Labor Center, estimates that he and other Aurora nonprofits have helped several thousand, mostly by getting them food, clothing and work permits.

In Colorado, state and federally-funded human service organizations responding to a migrant crisis can only be set up at the county level. Unlike Denver, which is both a city and a county, Aurora spreads across Adams, Arapahoe and Douglas counties, and none of those counties have put continuous funding toward the influx of migrants, Alvarez says.

Without the same resources as Denver, Aurora relied on the Aurora Migrant Response Network, a band of about fifty nonprofits that includes groups like the Dayton Day Labor Center, the Village Exchange Center, Project Worthmore, Aurora Community Connection and Jesus on Colfax.

Nonprofits in the Migrant Response Network see the Aurora City Council resolution mostly as “a statement on the mood of council” and don’t worry about the council or other city officials doing anything to them, says Alvarez, who heads the group. But they are worried about what kind of attention they’ll attract because of the resolution.

“We’ll see how this plays out,” Alvarez adds. “There’s a lot of uncertainty, and do we worry? Of course we do, especially with all this national attention.”

Amanda Blaurock, the founder and executive director of the Village Exchange Center, says the resolution “puts a target on our backs for people who are upset with the placement of Venezuelans in the Denver metro area” by depicting what they do “as nefarious and bad, when really, we are just furthering a nonpartisan mission and goal.” She considers the resolution “a safety concern for the communities we work with,” she adds.

“It basically puts blame on nonprofits for providing services and programs to community members that have done nothing wrong, and we all did it legally,” she says. “By doing this, it makes all of us look like we’ve done something that’s inappropriate.”

The nonprofits were unfairly roped into Aurora’s gripe with Denver, she adds: “Nonprofits have no place in that resolution. I would have preferred that they kept it between the municipalities, which is where the political positioning is.”

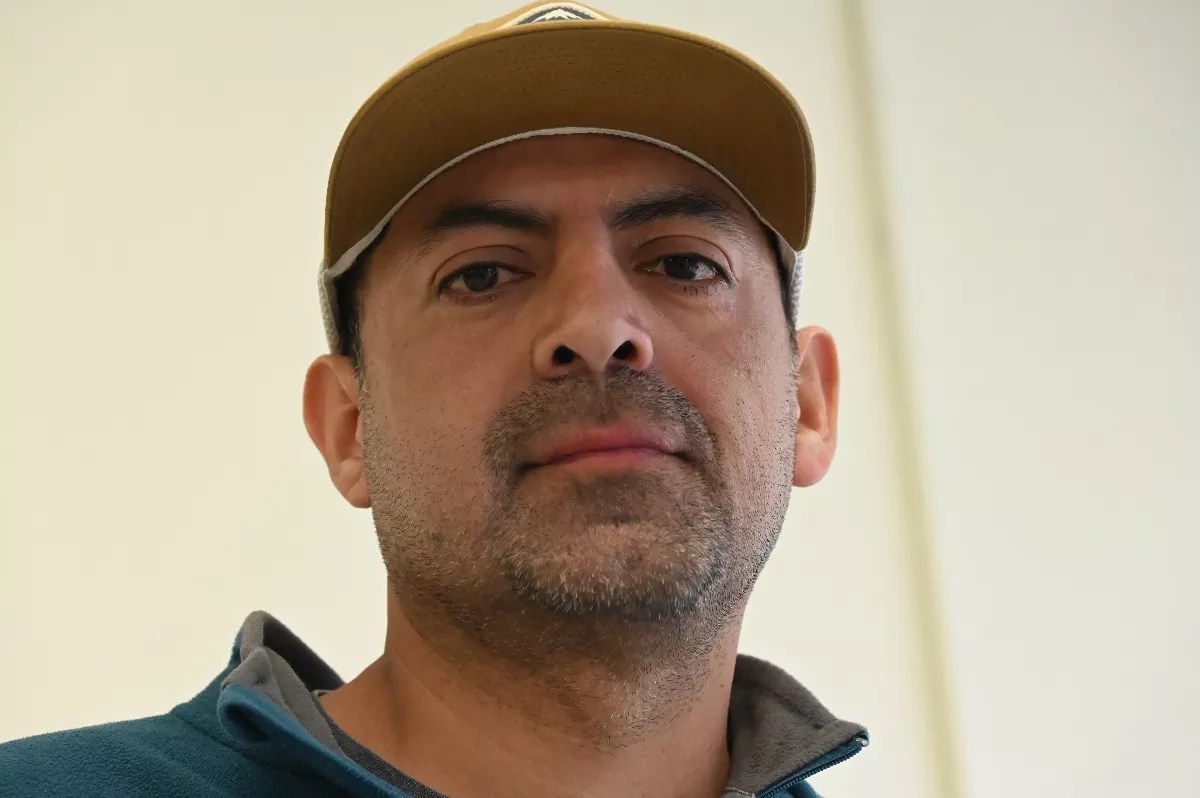

Amanda Blaurock, executive director of the Village Exchange Center, believes her nonprofit and others like it don’t need to be brought into Aurora’s fight with Denver.

Bennito L. Kelty

Chris Gattegno, who runs Aurora Community Connection, agrees that the resolution is political. “It’s not an accident that Jurinsky, who spoke at the rally, is behind the council resolution,” he says.

“This is a step taken by a mostly conservative city council toward appeasing Trump and playing into the Republican Party’s rhetorical argument about migrants,” he adds. “They are feeling the pressure from Aurora being so much in the news lately, as well as the narrative about gangs overtaking the city – even though they all know it’s completely exaggerated to the point of being untrue.”

Gattegno suggests that Aurora is picking a fight with Denver to save face.

“Blaming Denver for the increased number of migrants is a convenient way to shift the blame,” he says. “Which is a constant tactic in Trump’s playbook, instead of working collaboratively with the City of Denver to tackle this huge crisis.”

The Migrant Response Network had some input on an Aurora City Council resolution in March that committed the city to not funding any support for migrants and reaffirmed its “non-sanctuary” city status. But Alvarez says its input wasn’t requested this time.

According to a joint statement from Denver-based nonprofits Papagayo and ViVe Wellness and the Aurora-based Village Exchange Center, “The recent council resolution presents a risk of diverting attention away from critical community issues and could potentially undermine the valuable work our organizations perform in public service.”

The nonprofits defended the immigrants they help in the statement, saying that their arrival “enriches the social and cultural fabric of the community,” and that the organizations are committed to “upholding the dignity of those we serve.”

Venezuelan migrant Moises Didenot, who lives in the Edge of Lowry, a CBZ property at 1218 Dallas Street, says he and his neighbors found their apartments through Papagayo. Another resident at the Edge, Jefferson Medina, says he was placed there with the help of a church, Ministerios Fuente de Vida Internacional. Neither Papagayo nor Fuente de Vida responded to requests for comment.

Several residents at the Edge and some people who’d lived at 1568 Nome Street, the CBZ property shut down by Aurora in August by the city, told Westword that they had been in their units for more than two years – pre-dating the most recent influx of migrants and long before their landlord started blaming problems on Venezuelan gangs.

When migrants started coming in large numbers this past winter, Denver rented entire hotels and motels to shelter them. One, the Quality Inn at 1011 South Abilene Street, was in Aurora. The City of Denver has been working with Papagayo and ViVe Wellness to place about 800 migrants in apartment buildings with six months’ rent through the Denver Asylum Seekers Program.

Chris Gattegno, the executive director of Aurora Community Connections, tells West African migrants the importance of learning English in the United States. He believes Aurora’s latest resolution to “investigate” nonprofits like his is a political stunt.

Bennito L. Kelty

Aurora City Council wants City Manager Jason Batchelor to request records from Denver and the State of Colorado to determine how much money was spent to put migrants in Aurora, how many migrants were “placed” in Aurora and which nonprofits helped, the resolution notes.

According to new Aurora City Attorney Peter Shulte, who was sworn in at the beginning of the council meeting, the resolution is “not focused on the nonprofits, they’re focused on whether, for lack of a better term, our neighboring jurisdictions have been good neighbors. The information we get via this [Colorado Open Records Act] request could show nothing happened.”

At the Trump rally, Jurinsky vowed that “the days of Denver running Colorado are over.” Even though Shulte said the goal of the resolution is to keep Denver accountable, other councilmembers worry that it will pit angry residents against Aurora’s nonprofits as well.

Council rep Alison Coombs voted against the resolution because “we’re making people unsafe with the rhetoric we’re using,” she said, adding, “We’re scapegoating migrants and migration for an issue that we’ve had that’s been ongoing,” which is code violations at apartments.

The other vote opposing the resolution came from Crystal Murillo, who said she worried the resolution would lead to “a list of organizations that are now associated with immigrants and that in the future this body is going to deny funding.”

“I don’t believe we should be funding nonprofits fundamentally,” Jurinsky responded.

Councilman Steve Sundberg, who voted in favor of the resolution, said that Denver “placed people in Aurora, and they did it in an irresponsible manner” because it “walked away from them. There was no case management.”

But he gave kudos to some Aurora nonprofits, saying, “There’s a lot of nonprofits out there that are doing a fantastic job, coming together and solving a lot of our problems.” As an example of a “great” nonprofit, Sundberg named Village Exchange Center because it “does follow up and has case management.”

“I appreciate Councilman Sundberg’s support and acknowledging the good work we do,” says Blaurock, who notes that case management takes funding.

Alvarez questions whether Aurora can still brag about its diversity and large immigrant population if city leaders are going to keep passing resolutions like this one and the one approved in March. “Aurora is very flashy about [being] ‘a World in a City,'” he says of the city’s slogan. “Are we?

“On the flip side, we have these two resolutions…and it’s a contradiction that, as a city, we’re going to have to figure out.”