Lakes at Centerra Facebook

Audio By Carbonatix

The Lakes at Centerra, a Loveland development that sits at the intersection of Interstate 25 and Highway 34, is Colorado’s only National Wildlife Federation-certified Community Wildlife Habitat, earning that official designation by educating people about habitat restoration, making homes and community spaces animal-friendly, and encouraging native species in landscaping. But soon it could have fracking underneath that landscaping.

The development is part of Centerra, a real estate project developed by McWhinney, a company owned by Chad and Troy McWhinney that will have nearly 800 homes when completed. Now some Centerra residents, who say they were drawn to buy homes in the development because of its connection to nature, proximity to Boyd Lake and lack of big-city noise, are worried that fracking would destroy the outdoors-focused community.

“I’m angry, I’m devastated; it’s sad,” says Vanessa Wagmer, who bought her home in 2020. “McWhinney built up every inch of the land with homebuilders, and now that there’s no room left to build, they’re magnifying their wealth.”

The proposed drilling deal is “unfortunate,” according to Dawit Kiflemariam, program coordinator with the National Wildlife Federation, who adds that “this project won’t affect the status of their Communities Wildlife Habitat Certification, but…will have a negative impact on the environmental health of the community long term if launched. We hope our programs can continue providing avenues for the community to restore habitat for pollinators and create wildlife-friendly spaces.”

In a January 19 Zoom meeting called by Troy McWhinney, he shared details of the fracking deal, which has been in the works for a decade. The current plan calls for 26 wells on two pads, one west of Interstate 25 and one east. Drilling, which could start by 2023, would take six months to a year; the wells would be active for 25 years.

“I very much respect the oil and gas industry, as they work very hard to produce the oil, gas and energy which is a natural resource product that I use, and most people around the world use, every day,” McWhinney said, adding that since he thinks it will take a long time to transition to fully renewable energy, he’ll support non-renewables until then.

He began his presentation by explaining that he grew up in a planned community in California developed by Chevron Oil, and showed pictures of oil wells in backyards there. McWhinney then noted that his high school mascot was the Oilers. The more he learned about fracking, he said, the less worried he got.

“He begins by saying where he grew up, and that immediately started frustrating me,” says Tamara Fairbanks, a Centerra resident since 2016 who also grew up in California. “He said he could see an oil well where he grew up. Pardon me, but what does that have to do with anything? Just because it was okay forty years ago doesn’t mean it’s okay now. It’s not okay.”

At the meeting, McWhinney said that original proposals for the Loveland development had more wells, but that over time, the plan was consolidated to two pads that will get access to the minerals underneath the entire community through horizontal drilling and fracking. McWhinney, who lives in Centerra, noted that his home will be one of the closest to the western oil pad.

“I’m not trying to show you what’s right or wrong,” he repeatedly emphasized. “I’m trying to show you what I’ve learned over the last fifteen years of what’s happening in northern Colorado.”

He also repeatedly stated that his goal is to reach as many people as possible. But when contacted by Westword, MRG, the McWhinney-owned entity in charge of the fracking project, did not make him available for an interview and sent a statement instead.

“We have been transparently working on our plans for responsible energy development for over ten years and we look forward to working with the City of Loveland and the State of Colorado to meet their strict standards,” the statement says. “Like our new and longtime community members, we also value, and will do our part, to maintain the quality of life in Loveland.”

According to an MRG spokesperson, no official plans have been submitted, and no details beyond those shared at the town hall are available. The company isn’t comfortable discussing the issue with media, the spokesperson added, because Colorado Rising, a nonprofit that works to protect Colorado from the impacts of oil and gas development, is helping citizens organize against the proposal.

Troy and Chad McWhinney own the mineral rights under Centerra.

Colorado Rising

Mary George, who moved to Loveland around two years ago, first heard about the fracking plan on NextDoor earlier this year, then attended the Zoom meeting. Rather than alleviating her worries, it reinforced them, she says. She became even more concerned when she learned that Loveland City Council wouldn’t hire a panel of experts to assess the impact fracking could have on the area.

During a February 1 meeting, Loveland Mayor Jacki Marsh and Councilwoman Andrea Samson said that they wanted further investigation of the Centerra proposal, but the remaining seven councilmembers disagreed. “We’re sitting here beating around the bush when the Colorado Oil and Gas [Conservation] Commission has already done immense amounts of homework and they have the expertise in the area,” says Dana Foley, who was elected to the council in 2021.

Foley says he’s learned a lot about the oil and gas industry through various jobs in which he managed safety and compliance, such as safety manager for CTAP, which provides tubulars and casing for oil wells throughout Colorado. He’s seen the industry evolve to become much safer over the years, and that includes fracking, he adds.

“When I look at Troy McWhinney, I look at it like this: Everyone says, ‘Oh, he’s a businessman,'” Foley explains. “You’re right, he’s a businessman – so let’s look at it from a businessman’s perspective: Would you ever dump raw sewage in your car before you try to sell it? No. As a developer and as an owner, the last thing you’d want to do is create a negative exposure to your property, so there’s a financial benefit to do it the right way and make sure that it’s safe.”

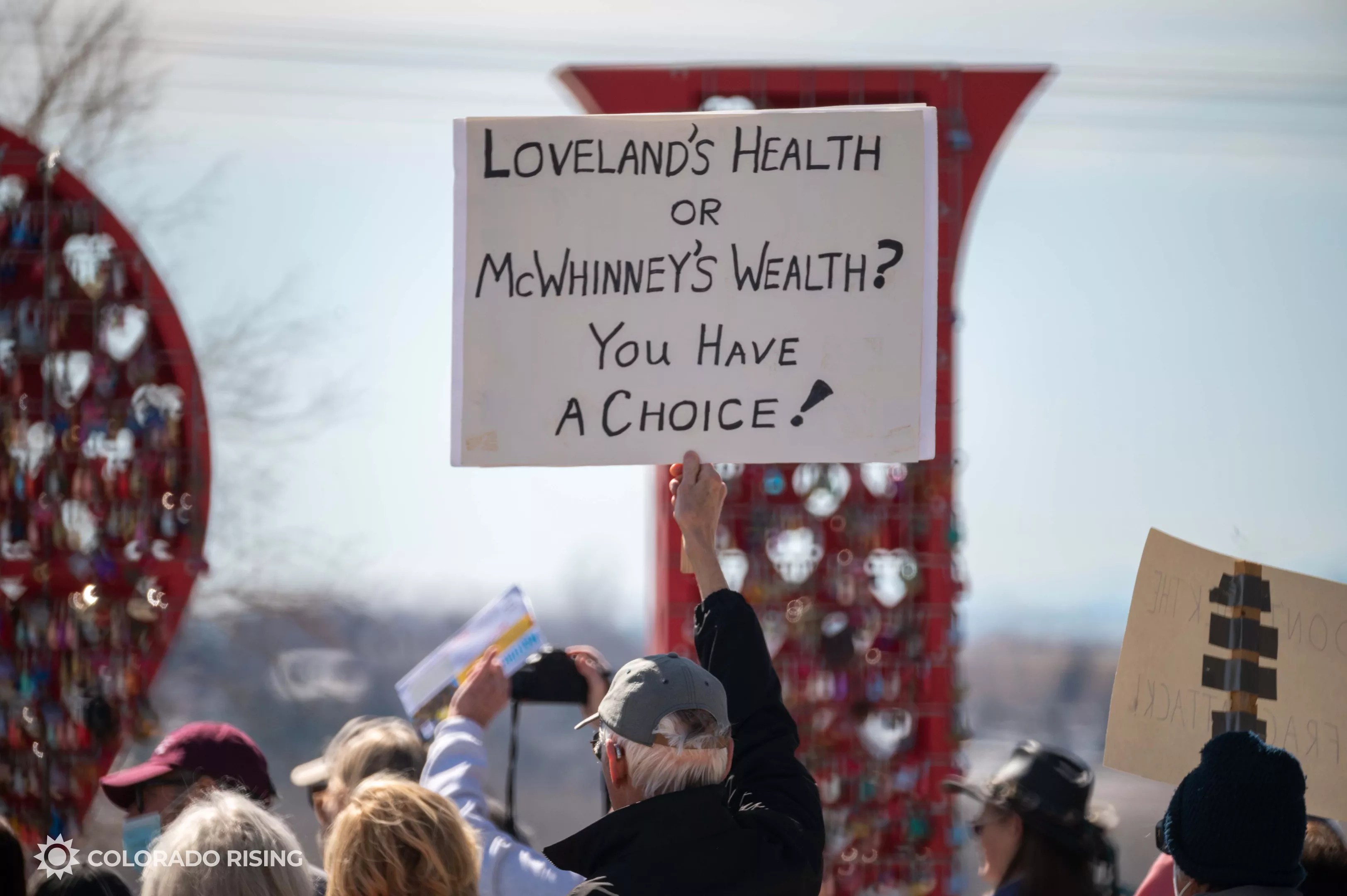

Some Loveland residents hope to stop the fracking plan.

Colorado Rising

But some residents wonder whether the proposed plan is a safe way to drill for oil, and they shared their concerns at a March 12 rally partially organized by Colorado Rising.

“Just getting a chance to connect with the community and knowing that I’m not alone, I’m not the only one who feels this way, gives me some hope that we could stop this,” says Wagmer.

George is particularly worried about the amount of water that fracking uses, which ranges from 1.5 million to 16 million gallons of water per well, according to the United States Geological Survey. “We don’t get that water back,” George says. “My concern for that stems from the fact that we’re currently in a drought. You want to use our water to frack…and cash out on our city? We need water to survive.”

Residents have questions about air quality, too. George walks her elderly dogs every day, and Fairbanks has asthma. Both say that air quality is already an issue in the area, and they don’t want any project that could make things worse. In addition, neighbors are worried about potential cracks in their foundations and how these could impact their home values, Fairbanks says. They also are wary of the noise and light pollution that could come with construction.

During the Zoom presentation, McWhinney said that environmental concerns would be addressed during the permitting process that will begin this year. Both the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission and the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment will have to approve permits for the project, adhering to standards largely established by the Environmental Protection Agency.

His experience with the industry helps Foley feel comfortable with the situation, and he hopes residents will do their research. “On city council, it’s not that I don’t hear their concerns; it’s that I understand, sometimes, a little bit of information that they may or may not have gotten,” he says.

George lives just south of the Lakes at Centerra, close to Troy McWhinney; one of the proposed oil pad sites is near her home. As a graduate student studying environmental engineering, she’s gotten lots of information about fracking and discussed it in her classes, but never really conceptualized it until now – and it hasn’t been a pleasant reality check, she says.

Foley supports the project, in part because he’s concerned about what Loveland could lose financially if the proposal doesn’t go forward. He notes that in nearby Wellington, there are many oil pads just over the border in Weld County, which has more relaxed oil and gas regulations, that use horizontal drilling to access minerals underground in Larimer County.

As a result, though minerals are extracted from Larimer County, Weld County gets the tax money from the operation. McWhinney could take the same approach, he suggests, moving his oil pads slightly more east and circumventing Loveland’s stricter regulations. Although this isn’t something McWhinney has ever said he would do, Foley says that he would prefer that the project oversight – and tax dollars – stay in Loveland.

“The folks in Loveland would not have gained a thing other than they still have the increased risk of the traffic and the noise and the light,” he says, “whereas, if we keep them in the city, we can review…those plans and we get a say in that. So do we get a seat at the table, or do we not get a seat at the table?”

Foley acknowledges that the operation would likely cause some extra emissions, but says he believes that the incentive of a good business image and Loveland’s strict regulations would minimize that risk. “People that are concerned about the health effects, there is a greater health crisis in their pantry than there is in the environment,” Foley says, adding that his wife is a nutritionist and often tells him about health problems caused by sugary drinks and products.

George is planning to have a child after she finishes earning her master’s degree. She’s read studies about babies with low birth weights born to women who live near fracking sites. “Why should my potentially healthy baby be impacted by someone who wants to use my city to make money?” she asks.

On the other end of the spectrum are retirees or those close to retiring, such as Fairbanks.

When she bought a new townhouse at the Lakes at Centerra last year, she hoped it would be her retirement home. She’d considered leaving Colorado because the dry climate and altitude aren’t good for her asthma, but decided to stay because she thought the wildlife focus of the development, and the nearby trails provided by the High Plains Environmental Center, would keep her healthy and improve her lung capacity.

Now she wonders if it will be a healthy place to retire after all.

Wagmer had moved her aging mother into her home, fitting the building with larger doors, a ramp and other features to make it accessible. Her mom is immunocompromised, amplifying Wagmer’s worries about the risks of air pollution or groundwater contamination. “If I had known that there were plans, or potential plans, to frack underneath my house, there’s no way I would have bought this house,” she says. Fracking and mineral rights never came up in her home-buying process, she adds, and no one went over the paperwork with her.

“I admit it,” Wagmer says. “I signed it without reading it fully, but I feel there’s more responsibility on the builder’s side. How could I know to ask about that?”

Fairbanks didn’t look at the fine print about mineral rights, because she bought a condo and wouldn’t own land. But she’s upset that Centerra brags about its ecological focus. “It’s just really advertised as an environmentally sustainable community,” she says. “There was no disclosure whatsoever, so when this came out…I feel betrayed.”

George hopes COGCC will intervene. Though the wells will comply with the 2,000-foot setback requirement, instituted by COGCC in 2020 after the Colorado Legislature changed the organization’s mission to emphasize protecting public safety and the environment in 2019, she still thinks they’re too close to homes, schools and hospitals to make sense.

“The best thing that people need to realize is that public safety is a priority of city council, as well as the developers, and if someone is not doing something right, we need to make sure that there’s measures in place to hold people accountable for that,” Foley says. “It doesn’t matter what field you’re in – nothing is without risk.”

But while Foley doesn’t think McWhinney will do anything wrong, Wagmer isn’t willing to take that chance. Even legal fracking isn’t safe enough for her, and she’s preparing to sell her house if the plan goes through.

Fairbanks will, too.

“I was so excited when I found this place. I found it just before Christmas,” Fairbanks says. “Now I’m just disappointed and angry.”