Evan Semón

Audio By Carbonatix

“You have my word,” Mayor Michael Hancock said during his State of the City speech in July. “We are going to continue to deploy every tool available, with a goal of lifting thousands of people out of homelessness over the next two years, including those who are living on our streets in the most unsafe and unhealthy conditions.”

Over the next two years, because that’s how much time the term-limited Hancock then had left in the mayor’s office, where he had already spent eight years. To bridge the gap between the current administration and the next one, Hancock’s Department of Housing Stability (HOST) just enacted a Five-Year Strategic Plan to tackle the issues of homelessness and housing in the city.

But is it too little, too late?

While many service providers suggest that Hancock made numerous missteps on homelessness, they believe the city’s current trajectory is positive. It just took too long to get to this point, they say, adding that Denver would have been much better positioned had Hancock acted more efficiently – and earlier.

And Hancock himself admits: “Major and large, and small- and medium-sized cities – everybody’s still trying to figure this out, but obviously a lot of knowledge that we’ve been able to gain over the years I wish we had in 2011, when I walked in. We would have been able to preserve a lot of the resources and direct them more appropriately, and set up better systems almost immediately.”

But the story of how the City of Denver has handled homelessness didn’t start with Hancock…and it won’t end with him, either.

An abandoned campsite in 2012, the year Denver passed the camping ban.

Sam Levin

From Invisible to Everywhere

“Contemporary homelessness really exploded in this country in the early 1980s, and that is when federal housing programs were decimated. Ronald Reagan really slashed federal housing programs enormously, and they’ve never recovered from that,” says Maria Foscarinis, founder of the National Homelessness Law Center and an adjunct faculty member at Columbia Law School.

“This is largely an issue that has grown to this point in my lifetime,” says Britta Fisher, Denver’s chief housing officer and the executive director of the Department of Housing Stability. “The level that we’re seeing now, I think we can look toward federal policy decisions [such as]…the deinstitutionalization of mental health, of then not having robust community investments to really care for people who were no longer in those institutions and have persistent needs.”

Homelessness wasn’t really on Denver’s radar in the early ’80s, when Federico Peña became mayor in July 1983. But that changed quickly as the effects of the federal changes rippled through cities. A January 1984 Washington Post article highlighted how mayors across the country were struggling with the issue of homelessness, and reported: “Denver Mayor Federico Peña said that, despite low unemployment and a mild climate, his city has been unable to cope with the mentally ill and thousands of homeless job-seekers from other regions.”

The Peña administration started tackling the issues, and its work led to the formation of the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless. “The organization grew out of a convening by Mayor Federico Peña in 1984 and was incorporated then,” recalls John Parvensky, the organization’s longtime CEO and president. “I joined in 1985, when the organization had a staff of six and a $100,000 budget.”

Under the administration of Mayor Wellington Webb, who took office in 1991, the city continued addressing the issue of homelessness. “The city at that time was still learning more about the issue because many of the homeless became homeless after the federal government deinstitutionalized mental health,” says Webb. “Our initial response was for the city to purchase two buildings.”

The city leased one of those buildings to the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless and then set up another with about fifteen units for youth experiencing homelessness, Webb recalls.

“Contemporary homelessness really exploded in this country in the early 1980s, and that is when federal housing programs were decimated.”

Service providers who’ve been working in Denver for decades didn’t see the city putting a significant amount of money toward solving homelessness, however.

“The Webb administration, we often said, they just didn’t use the word ‘homelessness,'” says Lindi Sinton, vice president of program operations for Volunteers of America Colorado, who’s been with the organization for over four decades.

But Denver woke up during the 2003 mayor’s race.

“We had a candidates’ forum at the St. Francis Center for that election,” recalls Tom Luehrs, executive director of that organization, which helps those experiencing homelessness. “I think there were eight people running for mayor. So we’re talking back in 2003. We asked the candidates all the same questions, and the question was, ‘What are we going to do about people experiencing homelessness?’ And it stuck with me that at the time, a pretty unknown entity, Hickenlooper, said, ‘This is an issue that we can do something about.’ So I think that was significant, because I think he had thought about the issue ahead of time.”

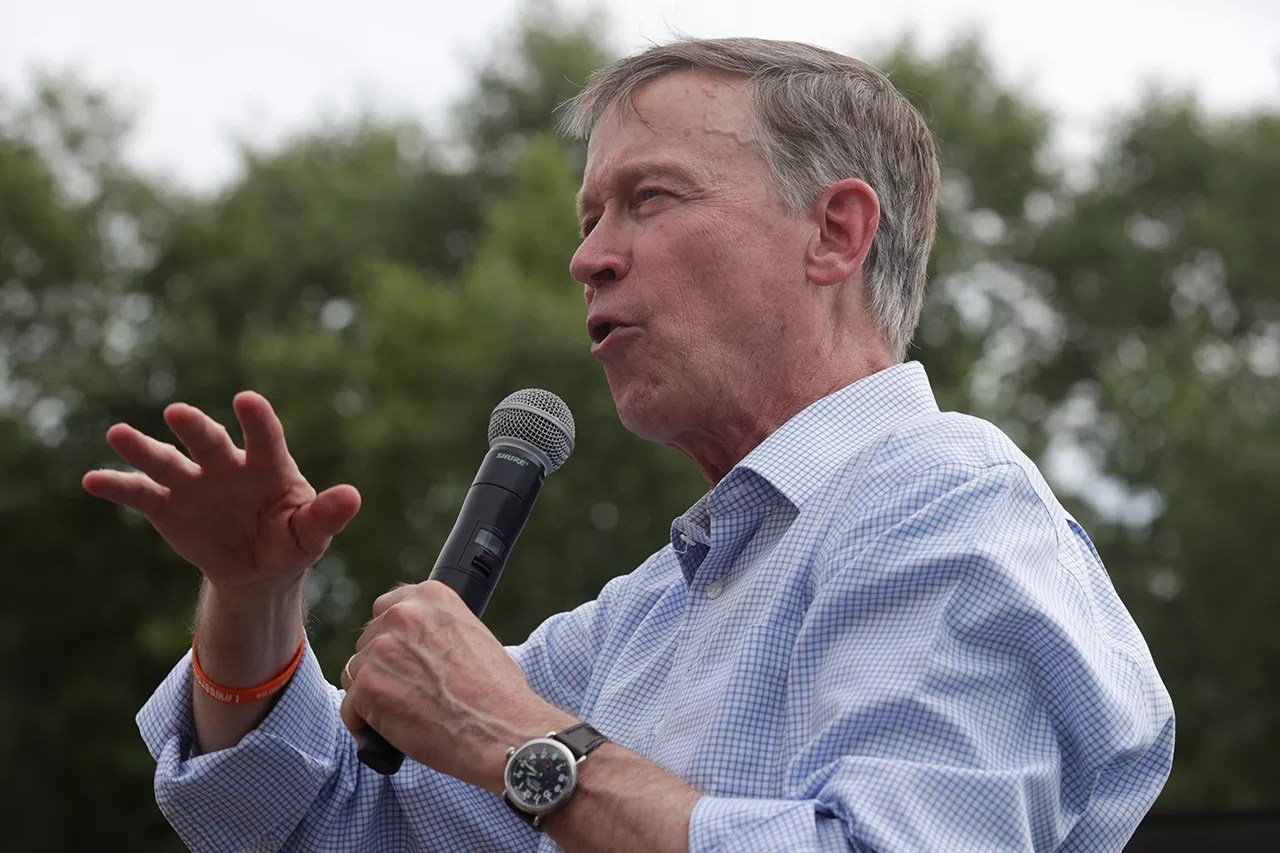

John Hickenlooper, who went on to win the 2003 mayoral race, says that he became interested in homelessness back in 1988, when he and some business partners were working to open the Wynkoop Brewing Company in a run-down part of LoDo. “Our rent was one dollar per square foot per year, which was almost free,” he recalls.

“There were these two guys that we called ‘bums’ – that’s not politically correct – they were down on their luck, they would sleep in our vestibule,” remembers Hickenlooper, who says that the Wynkoop partners wound up hiring the two men to help renovate the building. “It seemed like there needed to be a solution. These guys wanted to work. We genuinely liked them.”

In 2004, Mayor Hickenlooper’s administration convened the Commission to End Homelessness, a coalition of service providers, business community members, elected officials and individuals experiencing homelessness that was tasked with advising the city on the issue and creating solutions.

The administration really “embraced the word ‘homelessness’ as something people could connect with,” Hickenlooper recalls.

“I hired a woman named Roxane White to be my head of Human Services, which is a big city agency. Back then it had 1,300 employees,” Hickenlooper notes. Before taking that position, White had headed Urban Peak, a small service provider for youth experiencing homelessness. She continues to work with the city on homelessness issues as a consultant today. (White declined an interview request, saying it would be inappropriate given her ongoing work for Denver.)

In 2005, the Hickenlooper administration finalized Denver’s Ten Year Plan to End Homelessness. It was an answer to a challenge put forth by the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, which asked mayors to develop strategies to end homelessness in their cities within ten years. Hickenlooper also created Denver’s Road Home, a team housed within the Department of Human Services that would focus on homelessness.

As mayor, John Hickenlooper focused on homelessness; as senator, he’s continuing the fight.

Getty Images

But Denver’s Road Home never actually brought Denver home on the issue.

“That wasn’t the way it was really supposed to be,” says Brad Meuli, CEO of the Denver Rescue Mission, referring to the ten-year tagline. “It was a ten-year plan to address the issues of homelessness. It wasn’t ever going to completely solve it. I think there was a lot of media hype. We weren’t the only ones in the country doing it. Everybody was putting together their own plan to end homelessness.”

Or as Hickenlooper puts it now, the plan was “aspirational.”

“Even if you don’t achieve it, the point is to get the whole community trying to achieve it, trying to address it,” he says.

And at the same time, Denver’s Road Home did spark successful public-private partnerships.

“A lot of private money was put into Denver’s Road Home to defray the cost,” recalls Councilwoman Debbie Ortega, who, having served on Denver City Council from 1987 to 2003, went to work for Denver’s Road Home before returning to council as an at-large representative. “The focus was to initially get people into the shelter system and then get them connected to housing resources.”

“People have forgotten since then, but the major-league sports teams – the Broncos, Rockies, Avalanche, the Nuggets – together they gave $2 million in cash. Nowadays, the teams rarely give cash,” Hickenlooper says. “We made it part of everyone’s civic duty that they should chip in.”

White hired Jamie Van Leeuwen, who had also worked at Urban Peak, to head Denver’s Road Home.

“We had a very collaborative approach,” Van Leeuwen says of how Denver’s Road Home coordinated with the Commission to End Homelessness. “We really tried to create a seat at the table for everyone.”

“The ten-year plan was very ambitious for us at the time, and Denver’s Road Home commission helped to advise it and move it along.”

But while Hickenlooper is widely credited by service providers for successfully uniting them with city officials and creating powerful alliances with the business community, his administration didn’t dedicate a lot of money to the issue. Over the ten years that the plan was in place, the city spent $72.3 million in public and private dollars on Denver’s Road Home.

“The ten-year plan was very ambitious for us at the time, and Denver’s Road Home commission helped to advise it and move it along, but the financial resources weren’t there to the degree they are today,” says Sinton. “The knowledge, the data – a lot of the things were not in place in order to carry it out and track it.”

Hickenlooper acknowledges as much. “We had so much success fundraising in that initial two- or three-year period,” he says. “We didn’t put as much time as we probably should have into long-term funding. Many people get excited for something like this in the short term, but don’t buy in in the long term.”

The plan did make progress on some of the important issues it set out to fix, including chronic homelessness. A 2010 Denver Post article noted that the number of “chronically homeless in the city and county of Denver dropped to 343 in 2009 from 942 in 2005.”

“That’s almost two-thirds that we did in basically five years. That’s not insignificant,” Hickenlooper says.

But the city’s plan also hit a major bump midway through that ten years.

“It ran into an unprecedented recession with massive unemployment. Homelessness is 100 percent correlated with unemployment rates,” says Councilwoman Robin Kniech.

An official visit to an unofficial encampment in 2020, pre-sweep.

Michael Emery Hecker

Street Sweeping

As Denver battled back from the recession, Hickenlooper ran for governor in 2010 and moved up to the Colorado Capitol in January 2011. Michael Hancock, who’d been serving on Denver City Council, won the 2011 mayor’s race; he took office that July.

“When Mayor Hancock was first elected, my sense was that he thought that addressing homelessness was Mayor Hickenlooper’s thing,” says Parvensky. “Initially that wasn’t a high priority, and he was kind of content to let things, to let the processes that were set in place, continue.”

“I have the utmost respect for John Parvensky, but I would say that is not an accurate recounting. Homelessness has always been a high priority for Mayor Hancock, from day one,” responds Evan Dreyer, Hancock’s deputy chief of staff who has been with the administration since 2011.

Early on, Hancock tapped Bennie Milliner, an Air Force veteran, for executive director of Denver’s Road Home. “One of the jobs I had was to transition that budget from predominantly private funding to government funding,” Milliner says.

But Milliner and members of the Commission on Homelessness began to disagree on how the money should be spent.

“With the title of executive director, I felt like budget issues were a part of being the executive director. I wasn’t appointed by the commission or given my initial tasking from the commission. That was as a representative of the mayor, so that meant of the city,” recalls Milliner. “We tried to involve them in decisions about where the money should be spent, but that was probably a point of friction in that they didn’t have the final say in the dollars.”

“I think that a lot of what happened with homelessness was due to these larger economic forces.”

“I think that a lot of what happened with homelessness was due to these larger economic forces,” notes Kniech, “but I do feel that we were less prepared to respond because the city did not properly utilize the commission and because homelessness was kind of buried within Human Services.”

Milliner also caught flak from service providers because of his perceived lack of experience in the field. “I like Bennie, but it was like dropping somebody into a place that they’ve never been before. You’ve got to do a lot of catch-up,” says Luehrs.

But Milliner counters this critique. The mayor approached him to make use of his “experience dealing with problems and challenges and formulating a strategy to get to it,” he says. “He was relying on my 23 years of experience in the Air Force as a senior NCO to be able to try to diagnose what I saw as issues that needed to be addressed and hopefully solved, and so that was the approach we took.”

While the Hancock administration and commission were clashing, the mayor made a move that greatly complicated relationships with those working in the area of homelessness. Working with then-Councilman Albus Brooks, in mid-2012 Hancock started pushing an unauthorized camping ordinance. Also known as the camping ban, it would make it illegal for individuals to shelter themselves using a tent or sleeping bag outdoors without permission from a property owner. And for most public land in Denver, the property owner is the city.

“The mayor was pretty adamant that the camping ban was necessary, and he defended it and advocated for it as a way of essentially forcing people into shelter and service,” Parvensky says. “He’s never wavered from his belief that only through the threat of enforcement would people then access housing and services. We’ve refuted that notion many times.”

“It’s very resource-intensive. It’s expensive. We don’t deny that. And there are opportunity costs,” Hancock acknowledges. “Obviously, we’d rather spend those resources on housing, but we are also dealing with individuals who, for the most part, are service-resistant and have some compounding behavioral health challenges. We’re not trying to criminalize them. We’re simply trying to help people.”

Denver City Council ended up passing the camping ban by a 9-4 vote. Both Ortega and Kniech voted against it.

“Ironically, we have more people living out on the streets than at the time it passed. What we’re doing right now is basically moving people from one location to another,” says Ortega, referring to the sweeps of homeless encampments that have become more common.

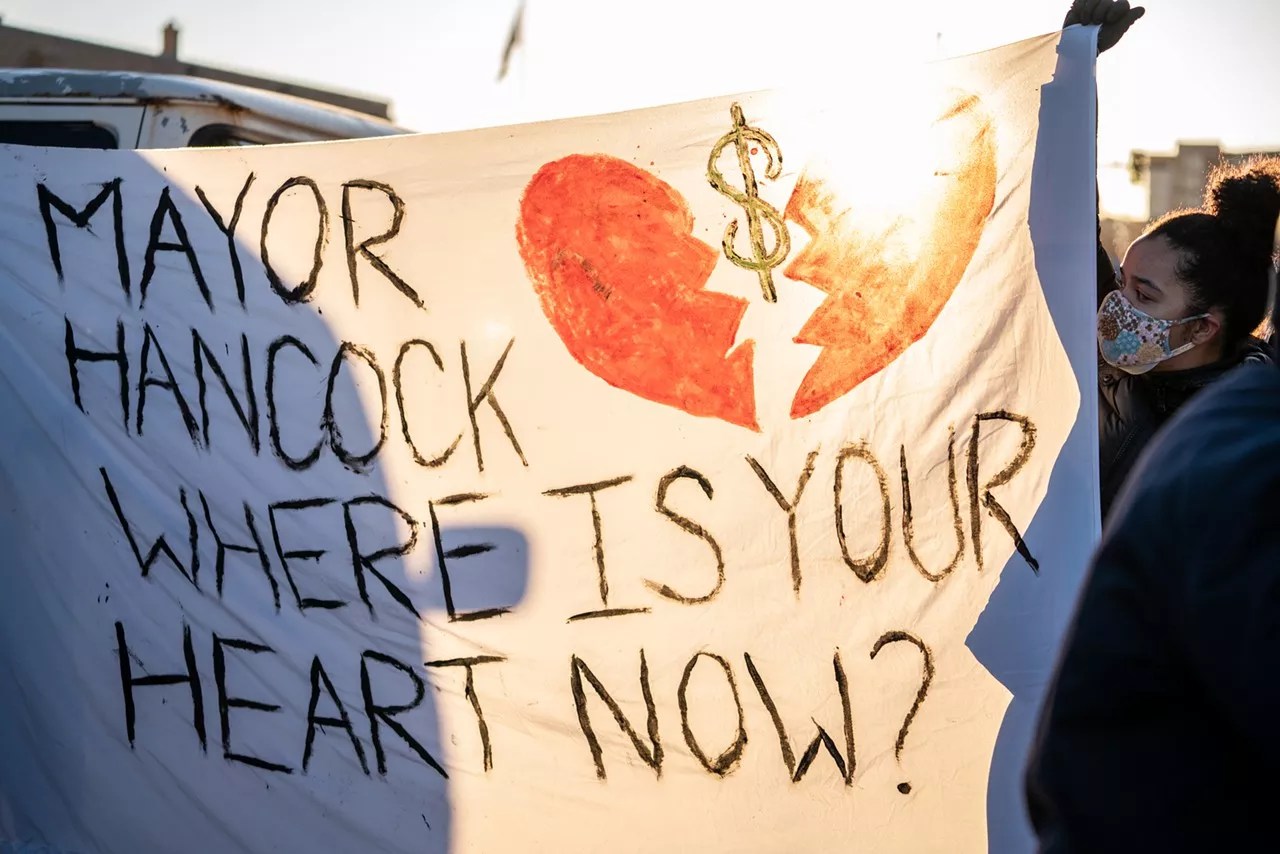

The mayor’s support of the camping ban remains the focus of protests.

Michael Emery Hecker

With the passage of the camping ban, Denver Homeless Out Loud, an advocacy group, emerged as a major force.

“I go to a sweep, and when people get moved to another location, when they get to that location, the police show up and tell them to move again and again and again,” says Ana Cornelius, an organizer with Denver Homeless Out Loud, whose members don’t mince words and hold the Hancock administration’s feet to the fire. “In my conversations out and about in the community, there is one thing we can agree on, and that is that Hancock is not doing a good job and Hancock is not taking care of the people.”

“There was always an intent of humanity when we were talking about [the ordinance],” responds Milliner, who notes that he was not involved in crafting the ban. “It got twisted by the really vocal advocates outside of the commission, particularly Denver Homeless Out Loud, and some of the providers. They never were comfortable with the unauthorized camping ordinance, and I understood that. I understood that. But there was also this sense that we could not allow homeless encampments to take over the city…although, as Denver Homeless Out Loud used to point out, if everybody came in for shelter, we could not provide shelter for them. That was a true statement. But that doesn’t mean that we couldn’t work toward it. And that’s what we see now, is the fruition of that. It’s taken time and money and resources.”

The advocacy work of Denver Homeless Out Loud in bringing together people experiencing homelessness to testify on key policy issues is unique in the landscape of municipal politics, according to Foscarinis.

“People who are homeless [in Denver] have really organized and led efforts to draw attention to the sweeps and draw attention to harmful policies and built a pretty broad coalition,” says Foscarinis. “To me, it’s always seemed a little bit surprising why Denver and why this mayor have not been more supportive.”

“The mayor was pretty adamant that the camping ban was necessary, and he defended it and advocated for it as a way of essentially forcing people into shelter and service.”

The camping ban and other laws that the city uses to justify encampment sweeps have been the subject of numerous legal challenges, including cases that resulted in a federal court order and a federal court settlement that set restrictions on when and how the City of Denver can conduct sweeps.

Andy McNulty, a lawyer with Killmer, Lane & Newman, LLP, filed the most recent lawsuit related to the city’s sweeps on behalf of Denver Homeless Out Loud. McNulty and DHOL were able to secure a preliminary injunction in federal court, requiring seven days’ advance notice before any sweep. “I think it’s clear that the Hancock administration’s legacy on homelessness is the camping ban and the homeless sweeps. Those are the two biggest, most expensive things that he’s done related to homelessness,” says McNulty, who notes that the city has spent a significant amount of money on homelessness in other areas, too.

“A lot of that money was poured into shelters, which was ineffective. I can’t say all of that money was wasted. I think a lot of people have been helped by the Hancock administration. But an equal, if not more, amount of people have been hurt by the Hancock administration’s policies,” McNulty says.

Under Hancock, the city began looking at another front in the battle against homelessness: the lack of affordable housing. In 2013, Hancock earmarked the first general-fund money for affordable housing.

And two years after enacting the camping ban, Hancock unveiled what would become one of his administration’s most successful approaches: At the Clinton Global Initiative in June 2014, Hancock announced that his administration would establish a Social Impact Bond program that would use private money to provide supportive, permanent housing for hundreds of chronically homeless individuals. If the project led to positive results, the City of Denver promised to repay the organizations that came up with the initial funding.

That announcement was Hancock’s first positive “imprint” on homelessness, according to Parvensky. The Colorado Coalition for the Homeless and the Mental Health Center of Denver ran the program from 2016 through 2020, and it was a “remarkable success,” according to Sarah Gillespie, associate vice president of metropolitan housing and communities policy at the Urban Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank that focuses on economic and social policy research. “What we think this shows is that if you’re offering supportive housing from a housing-first approach, the vast majority of people are going to take it up and stay.”

Private donations of over $8.6 million resulted in CCH and MHCD housing 365 individuals. Many lived in buildings owned by the two organizations, while others used vouchers to stay in units under other landlords.

“Of all the people that the service providers reached out to, 79 percent ended up moving into housing,” Gillespie notes. “That kind of dispels the false narrative around homelessness being a choice.”

“Even though we and the Mental Health Center did the work, the people who funded it were these investors, and the city made the commitment to reimburse them. Without the mayor’s support of that, it wouldn’t have happened. I give him credit for that, and it will be a legacy for them,” says Parvensky.

Hancock refers to the Social Impact Bond as one of the “real crowning jewels” of his administration’s work on homelessness. “I’m very proud of that effort,” he says.

In fall 2016, working in partnership with Kniech, Hancock also helped establish a dedicated affordable-housing fund, which was estimated to raise $150 million over a decade. “The housing fund does invest in two things: bricks-and-mortar supportive housing for people experiencing homelessness, and investing city dollars in supportive services,” explains Kniech.

Mayor Michael Hancock has recently upped the city’s spending on homelessness.

Brandon Marshall

From HOPE to HOST

But as the Social Impact Bond program was playing out, the Hancock administration struggled to determine what type of government entity could best address homelessness.

“Denver’s Road Home was always structured as a program within Denver Human Services for as long as I’ve worked in it. That was one of the structural challenges; it wasn’t a stand-alone agency protected in the city charter,” says Chris Conner, who served as head of Denver’s Road Home for a time and is now the director of homelessness systems strategies at HOST.

Although Denver was seemingly operating under a housing-first mantra, housing programs were mostly handled by the Office of Economic Development, while the service plans were spearheaded by Denver’s Road Home. And that agency didn’t have the authority or the funding necessary to truly do the job, suggest some service providers.

“I wouldn’t say there were two islands,” Conner says. “There were two different places in the city where a lot of that energy lived a bit more autonomously. What that requires is a lot more rowing of boats in between those islands.”

In 2017, Hancock announced that Erik Soliván, who had worked for the Philadelphia Housing Authority, would become the head of HOPE, the new Office of Housing and Opportunities for People Everywhere. That same year, Hancock disbanded the commission that had been advising the city on homelessness and moved Milliner to a job focusing on community engagement for the Denver Sheriff Department. Denver’s Road Home remained intact, working alongside HOPE.

The hopeful HOPE experiment didn’t last long. In February 2018, Soliván resigned.

“The structure was just everywhere, and there wasn’t in any way a clear chain of command to push an agenda forward. HOPE was just a political office designed to send a message, that was it,” says Soliván, who now works as chief development officer and chief of staff at the Tulsa Housing Authority. “This was intended to be window dressing. That’s why I said, ‘I’m done. That’s not what I came here to do.'”

According to Alan Salazar, Hancock’s chief of staff, “The mayor’s goal was to create a coordinating entity” with HOPE. It “was successful in some ways,” but “it became clear to us early on that we need to have a stand-alone agency,” he says.

“I just don’t think it’s fair to say that it’s window dressing or a political stunt. A lot of effort was put into the program. I just don’t think Soliván developed the relationships or coordinating skills to work in Denver,” Salazar adds.

In mid-2018, the city hired Fisher to be its first chief housing officer. Fisher, who had previously worked for Metro Caring, reported directly to the head of the Office of Economic Development.

“It’s like being in a kayak on the river. You can really put your paddle in, make moves and be nimble,” Fisher says of her work in the nonprofit world. “Now, this was the chance to be on the barge and really think about bigger moves and how we can move farther faster, and with bigger impact.”

In April 2019, a month before the last mayoral election, Hancock announced that his administration would be forming a new department: the Department of Housing Stability, or HOST, which would focus on housing and homelessness and also have a full departmental budget. After Hancock won the election in a runoff, HOST went live in October 2019 with Fisher as its head, and Denver’s Road Home and HOPE were essentially folded into the department.

“When I was hired, I saw that the city had learned that it was hard to have leadership over an area where there wasn’t authority and budget combined to that,” Fisher recalls. “I think some of those lessons learned really set me up for success as I came into the city.”

“That certainly provided some energy, some new leadership,” says Parvensky.

“I would say Britta Fisher now is a good, strong leader who knows the issues,” adds Luehrs.

“When I talk to other CEOs, there is not another city that has as coordinated an effort to try to address the issues of homelessness as Denver.”

The timing of HOST’s formation could not have been more serendipitous.

When the COVID pandemic hit in March 2020, the city had to be nimble in order to respond to increased homelessness and housing needs. Shelter strategies had to shift, since social distancing and disease-spread prevention were now requirements.

The city and local service providers moved many of Denver’s shelters to round-the-clock facilities. “When we took office in 2011, our shelters only operated six months a year. Today they operate twelve months a year and many 24/7,” says Dreyer.

The city supported the establishment of auxiliary shelters at the Denver Coliseum and the National Western Center in order to allow for social distancing. The city and service providers also began renting motel rooms for people experiencing homelessness who were vulnerable to becoming seriously ill or dying from COVID. And the city started to pour money into homelessness and housing, thanks in large part to hundreds of millions of dollars that Denver received through emergency COVID federal relief money.

In November 2020 – after turning down a proposal to overturn the camping ban just eighteen months earlier – Denver voters also approved a sales tax increase that will earmark tens of millions of dollars a year to a homelessness resolution fund.

“When I talk to other CEOs, there is not another city that has as coordinated an effort to try to address the issues of homelessness as Denver,” says Meuli. “Frankly, I’m awed that there’s this collaborative effort to try to address the issues of homelessness.”

The safe-camping site in Park Hill just packed up; the city has three more.

Evan Semón

The Numbers Game

The pandemic also led Hancock to consider alternatives to traditional shelters that he had long rejected.

For years, service providers and other advocates had suggested that the city allow the establishment of safe-camping sites where people experiencing homelessness could live in tents with access to bathrooms, showers and other services. Those who might not feel comfortable in the shelter system would be safer in such a site than in an unsanctioned encampment.

In the early months of the pandemic, a group of service providers, including Cole Chandler, executive director of the Colorado Village Collaborative, proposed setting up safe-camping sites in Denver as a harm reduction tool. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had been advising municipalities not to sweep encampments if individual housing was not available, so as not to further the spread of COVID. But the city was still conducting sweeps.

It took until July 2020 for the mayor, who was at first opposed to the idea, to agree to allow the establishment of safe-camping sites, which Chandler and other service providers call “safe outdoor spaces.” In December 2020, Denver opened its first two safe outdoor spaces at churches in the greater Capitol Hill area. While those two closed after six months, others replaced them – and service providers just opened Denver’s sixth safe-camping site (joining two others that are currently open), the first on city-owned property.

“Obviously, I wish they would’ve come around a lot sooner,” says Chandler, who has been working on homelessness issues in Denver since 2014. “I think the way that democracy works is that what people want to see, we have to make that real. We have to advocate for that kind of thing. I don’t think that there was a real strong coalition of people all calling for this thing together prior to 2020. You certainly had some advocacy groups calling for it, and obviously we wish that politicians would just listen to the expert voices, but democracy is a process of building support and building coalitions. I think the conversation shifted in 2020 – specifically, some neighborhoods and businesses getting behind the idea in a really different way.”

Hancock has now fully embraced the safe-camping site model, and his administration has earmarked $4 million for safe-camping sites in 2022. “As long as we have people who are on the streets unwilling to go indoors, we have got to have alternatives for them,” the mayor says. “And I think this is as good as I’ve seen around the country.”

“At the end of the day, I don’t think good leadership is having all the answers,” Chandler says of Hancock’s evolution. “Good leadership is being willing to grow and change and evolve. I think you’ve seen that on display with safe outdoor spaces in particular as a case study.”

“At the end of the day, I don’t think good leadership is having all the answers.Good leadership is being willing to grow and change and evolve.”

Using significant federal funding, the City of Denver has allotted $270 million to efforts to create affordable housing and fight homelessness in the 2022 city budget. In one year, that’s close to four times as much as the City of Denver spent on Denver’s Road Home in a decade.

And HOST has been expanding, growing from sixteen to eighty employees. “That is really great to see the energy come together,” says Fisher.

In January 2020, a Point in Time count – conducted annually by the Metro Denver Homeless Initiative – found 4,171 people experiencing homelessness on a single night in the City and County of Denver. Of that total, 3,175 were in sheltered settings, while 996 were in unsheltered settings. The count did not capture people who’d lost housing and were living temporarily with friends and family.

Around 29 percent of the people counted were chronically homeless. Over 36 percent had mental health issues, while about 31 percent had substance-abuse issues.

The 2021 Point in Time survey did not include an unsheltered count because of the pandemic. The sheltered count, however, had increased from 3,175 in 2020 to 3,752 in 2021. And service providers and city officials agree that the overall homelessness numbers were likely higher than in 2020 as a result of economic hardships created by the pandemic.

According to HOST communications director Derek Woodbury, the city currently has more than 2,500 beds across its network of congregate/non-congregate shelters and hotel rooms for people experiencing homelessness.

The number of shelter beds have grown, and so has the size of the private organizations that work with the city. The Colorado Coalition for the Homeless currently has a staff of 750 and a budget of $100 million.

People experiencing homelessness are everywhere in Denver, but given the different reasons they land on the streets, there’s not a single solution. Safe-camping sites will help bring some into safer settings. And then more affordable housing and permanent supportive housing will help others move into long-term settings. Meanwhile, those who are struggling with mental health issues and substance-abuse issues may be helped by newer programs like the Support Team Assisted Response (STAR) truck, which is staffed by a paramedic and a mental health clinician who respond to crisis situations that don’t merit a law enforcement response.

While the city continues to grapple with the uncertainties of the pandemic and the growing number of those experiencing homelessness, it now has a guide for its efforts. In November, Denver City Council approved HOST’s Five-Year Strategic Plan, which seeks to cut unsheltered homelessness in half and end veteran homelessness altogether by late 2026. The plan calls for creating 7,000 affordable homes; raising the total percentage of housing in Denver that is income-restricted from 7 to 8 percent; preserving 950 income-restricted rentals; and increasing the number of people who leave emergency shelter for permanent housing from 30 to 40 percent, and the number of families moving into housing from 25 to 50 percent.

“The Five-Year Strategic Plan and the Department of Housing Stability will act as bridges to the next administration. I think the homeless resolution fund, as a dedicated voter-approved funding stream, would be another bridge,” says Dreyer. “I think there are bridges that are in place.”

Kniech, who has spent much of her political career working on issues related to housing and homelessness, wonders if Denver residents realize that positive moves are being made. “Eleven years into my journey of public service, I still cannot find an effective way for people to see successes in this realm,” she says. “It’s invisible. Only our failures are visible.”

In Denver, the use of the camping ban is highly visible. So is unsheltered homelessness, on sidewalks and vacant spots all over the city.

Meanwhile, the Hancock administration’s productive moves on homelessness, including helping house 11,000 people experiencing homelessness over the past ten years, go largely unheralded. But Kniech points to the affordable-housing fund, the shift to safe-camping sites and the formation of HOST as major successes.

“We are better poised than we’ve ever been before with the infrastructure that we need in place in terms of a city department with the focus, with the resources, several dedicated funding streams, plus federal dollars,” she says. “I think we as a city continue to need to get more efficient at deploying dollars. I think we have a number of models that work. Our challenge is scale.”

We Can Do Better

That’s the challenge across the country.

“Every community in America is failing on homelessness,” Kniech adds. “That can’t be a coincidence that they’re all making the same bad decisions. It’s a national, structurally driven problem, and only national, structurally driven solutions are going to solve it.”

If President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better agenda is signed into law, the money in that package will help chip away at homelessness and housing instability nationwide.

Fisher is feeling optimistic about that. “I absolutely think the scale of the need that we are seeing right now requires federal partnership. I’m very hopeful about Build Back Better plans,” she says.

And Hickenlooper, who’s seen the challenges on both the local and national levels, is now working in the Senate to pass that bill.

“Build Back Better will have money for affordable-housing tax credits,” he notes. “It’ll have other money for housing agencies. I think it’s also going to have resources in there for vouchers. Obviously, the more we can get in that bill to create new housing, the better off for Denver and Colorado. … I’m on the side of create more housing and figure out all the different ways of doing that.”