Evan Semón

Audio By Carbonatix

In the dead of winter, Lindsey Paison stood at the edge of Englewood’s Cushing Park, looking for a 61-year-old man named Anthony.

Almost a decade had passed since Anthony’s sisters, Teresa and Evie, had seen or talked to him. All they knew was that he’d boarded a Greyhound bus in Hockley, a town outside of Houston, and headed north to Denver, where he’d lived before. They didn’t know if he’d ever made it back to the Mile High City, but if they could find Anthony, they wanted to give him a plane ticket to return to Texas, where Evie lives.

They didn’t have a photo of their brother beyond one from the late ’90s. “It was really outdated,” Paison recalls. “You can imagine being out on the street; your physicalities are likely to change, just because you don’t have access to the kind of stuff that the rest of us do. For all I knew, he didn’t look anything like the picture.

“It was bleak. There was no information on Anthony.”

This was the private detective’s first case involving a missing person presumed to be living on the streets, homeless. It would not be her last.

Lindsey Paison works for free for families looking for loved ones on the streets.

Bennito Kelty

Paison has been surrounded by the law all her life. Her dad, Casey, is an attorney who mostly deals with business and real estate. Her mom spent her entire career as a paralegal. And by the time Paison started her P.I. firm in the fall of 2021, she was already deeply interested in missing persons cases.

“I’ve had an interest in missing persons since I was five,” she says. “So when I started doing private investigations, it was headed in that direction, anyway.”

Paison grew up mostly in the Bear Valley area of southwest Denver, but before she started elementary school, her family lived in Glenwood Springs. That’s where her interest in missing persons began: Her father was a friend of Paul Skiba, who went missing in 1999 along with his nine-year-old daughter, Sarah, and a co-worker named Lorenzo Chivers. The three were never found; it was suspected that they’d been murdered.

The Skibas lived in Thornton, where Paul owned a moving company that Casey had hired for the family’s relocation to Denver. Paison remembers that she’d played with Sarah, and they’d gone swimming in a pool in Glenwood Springs. Sarah was “a nice girl, and her dad was a good guy, too. It was a shame what happened to them. Lorenzo, who went missing with them, was a good guy, also.”

After that, Paison developed a “near obsession” with missing persons cases. “She was quite young at the time,” her father remembers. “I think she really seized on that and became really interested in missing persons. … Every young, young person has something that happens, and it makes an imprint on them.”

Paison began watching police procedurals and cop dramas, starting with Law & Order (which she still loves), then CSI: Miami (a guilty pleasure she’s embarrassed to admit), Criminal Minds (she’s seen every episode) and The Rookie (she wishes she’d started watching it sooner). Now, two and a half decades later, her favorite show is The Lincoln Lawyer – even though it’s a legal procedural.

Growing up at the dawn of the internet, she spent hours combing through police reports from across the country that she found online. “It was probably an unhealthy obsession for someone who was five or seven years old,” she admits. “I spent many afternoons at my mom’s office with access to a computer. I was looking for missing persons pages, report after report, page after page.”

Paison soon developed “really good street smarts,” her father remembers, along with “skills about how to read a room and people.”

After high school, Paison bounced between Metro State University of Denver, the University of Colorado Denver, Community College of Denver and Arapahoe Community College, looking for a place to study criminal justice. Ultimately, she decided not to pursue a degree; for a time, she thought she wanted to become a homicide detective, but “I was starting to see such a change in how the community was responding to law enforcement. I saw how law enforcement was changing toward the community,” she recalls. That was right after the death of Elijah McClain in Aurora in August 2019, and the murder of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police the following May.

“We weren’t headed in a direction – as far as law enforcement was concerned – that I was interested in participating in,” she adds. “I wanted to be a cop in an environment where we were encouraging community policing, where officers were knowing people in their communities and it was more of a helping situation. Policing began to take a turn toward military-style policing, and I didn’t want any part of that.”

But she was still interested in missing persons mysteries.

The Skiba case is still unsolved. Paison has a case file with all of the information she collected, and she and her dad occasionally theorize about what happened to their friends. Although there were some doubts cast on Paul Skiba’s on-again, off-again girlfriend, Paison doesn’t think she’s a likely culprit. Instead, she points to Paul Skiba’s reported connections to drugs and gangs.

“In order to pull off a triple homicide, including that of a nine-year-old, and then hiding those bodies to the degree that they’ve never been located, that requires multiple people,” Paison suggests. “And you’ve got to have some people who don’t have a conscience.”

Fliers can be the key to finding missing persons who are living on the streets.

Bennito Kelty

Finally, Paison decided to follow her longtime interest and open a private investigations firm, Dark Knight Investigations. She chose the name because she wanted something that “portrayed strength, security and sounded kind of tough,” she says, even though her father thought the Batman connection might make it sound “too comic-y.”

Colorado had just ended licensing requirements for private investigators, and while Paison says she “was shocked and disappointed” by that move, it made it easier to set up a business.

By late 2021, she was working as an investigator for law firms, serving legal documents. Even today, her primary jobs involve tracking down witnesses for legal cases or people who skip out on debt payments and doing background checks on people, companies and real estate, as well as criminal and civil case research – “the basic legal stuff you would expect a private investigator to be involved in,” she says.

But she was still obsessed with missing persons cases, and only a few months after opening her business, she started volunteering with We Help the Missing, a national organization founded in 2014 by a Utah investigator who connects families looking for missing loved ones with volunteer private investigators in different parts of the country.

We Help the Missing had never looked for a homeless person before, and when Teresa and Evie filled out their intake form, Paison was the private investigator signed up to help. Anthony’s case landed in her lap on New Year’s Eve 2021.

At the time, she “didn’t even know if he was going to be in the state of Colorado,” she remembers. “He might have had the intention to come here, but he could have been here for a year, for all I know, and ended up in Oregon.”

She started by looking through databases with Anthony’s full name (his sisters asked that it not be used in this story) and birth date. Over the past thirty years, he’d bounced from Colorado to Texas and back to Colorado, likely to escape the hot weather. His sisters confirmed that most of the addresses Paison had found were old, but there was one listing for a mobile home in Mineral Point, Wisconsin.

Paison called the Iowa County Sheriff’s Office in Wisconsin to run Anthony’s name. “I didn’t know – maybe he was still there, he’s just in jail and that’s why he’s not in touch with anyone,” she says. After the sheriff’s department said that Anthony wasn’t a guest of the county, she reached out to the owner of the mobile home park. She had no luck there, but she did locate a former roommate of Anthony’s. Although he hadn’t seen him in years, he filled her in on a few details, including that Anthony suffers from mental illness and likes to drink, but hadn’t been using drugs.

Oh, and one more thing: Anthony liked to frequent Charlie Brown’s, a piano bar at 980 Grant Street in Denver.

“I thought, what the heck?” Paison remembers. She headed over to Charlie Brown’s and asked patrons there if they’d seen an older white guy, about six feet tall, going by the name of Anthony.

“People said, ‘Well, how the hell are we supposed to help you if you don’t even know who you’re looking for?'” she recalls. “I was just hoping that someone there would know a guy named Anthony, but unfortunately, nobody did.” She followed another lead to a trailer park in the Westminster area, but that was a dead end, too.

“People said, ‘Well, how the hell are we supposed to help you if you don’t even know who you’re looking for?'”

So Paison went back to basics and started looking on the Denver County Court website to see if Anthony had been issued any tickets or arrest warrants, “just to see if I could get simple tips on addresses to get a clue on where he was often.” When nothing came up, she decided to call the Denver Police Department.

Paison had already urged Anthony’s sisters to file a missing persons report, but Evie said that when she’d contacted the DPD, she was told that the department couldn’t look for him because he was transient, which “means they didn’t really consider him missing.”

“They had been giving her a hard time already,” Paison notes.

“Officers should not refuse to take a report based on a person’s housing status,” a DPD spokesperson tells Westword. “If there is a person who has been denied a report of a missing person, they should try to re-report and, if denied, ask to speak with a supervisor.”

When Paison called the DPD, she learned that Anthony had been hit by a car around East Third Avenue and Santa Fe Drive the year before. According to the police report, he was all right – and at least that showed he’d recently been in the area. “I was starting to feel better,” she remembers.

She kept talking to the DPD and was able to annoy a detective into a compromise. The detective told her her that if she kept his name a secret, he’ll tell her where Anthony might be.

Turns out that Anthony had been cited just a few weeks earlier for overnight camping at a park in Englewood. “Might be worth a shot,” the detective told her. “That seems to be an area that he hangs out in.”

Paison, who works from her home in south Denver, knew that place. After hanging up the phone, she jumped in her car and drove the seven minutes to Cushing Park, where it was ice-cold in mid-January.

“There were some very unsavory characters down in the park,” she admits. The first guy she approached offered her crack. “Oh, God, I don’t think we want to do that,” she thought to herself.

Then, behind the crack dealer, she noticed “a gentleman sitting on a park bench,” she says. “He was the only white man in the area, and I at least knew I was looking for a white guy. There was no thought in my mind that I was going to get lucky and this is him.” Still, she thought she’d ask him if he knew anything.

“I walked up and said, ‘Do you know a guy named Anthony who hangs out here?’ And he says, ‘I’m Anthony.'”

Stunned, she said his last name, and he confirmed, “Yeah, that’s me.”

Even though the photo she had was old, she knew she was looking at the right guy. After she got over the shock of realizing she’d found him, Paison explained to Anthony that she was a private investigator hired by his sisters “who are really worried about you. … You’ve been missing to them for all these years.”

Anthony was surprised by that, she recalls. He said he had been on the street since he’d gotten back to Denver from Wisconsin but had been beaten up several times and robbed of his belongings, which included the piece of paper with his sisters’ phone numbers. “That was the reason he was never able to contact them,” she says. “He just didn’t know how.”

Paison told him that in the time he’d been gone, his mother had passed away, as had another sister. “He was sad to hear” about their deaths, she says, “but he was more shocked than anything that people had been looking for him.”

They talked for another ten or fifteen minutes, and Anthony “had a lot of out-there stories that he wanted to tell me about,” Paison says, attributing them to his mental illness.

Before she left, she gave Anthony his sisters’ phone numbers. He promised he would call them, and he followed through. But he turned down the plane ticket back to Texas, where he could live with Evie. Instead, he decided to stay on the streets.

Lindsey Paison making the rounds in downtown Denver.

Bennito Kelty

After reconnecting Anthony with his family, Paison thought about all the other people in Denver who might need the same service, to be connected with missing loved ones living on the streets.

“It was his case that prompted me to take a look at what is happening in Denver with this rising homeless population,” Paison says. “I started thinking, his family can’t be the only family that’s going through this panic and this not knowing. There are people out here in Colorado who are experiencing homelessness for a multitude of reasons. I thought, ‘What can I do to help?'”

On February 23, 2022, she published a Facebook post offering her services as a licensed private investigator who could help find missing loved ones now believed to be homeless, and she offered to do it for free. She called it the Get Home Safely program.

“When most people hear about a missing person, they think of Elizabeth Smart,” she wrote at the start of her post. “What they don’t know, or often overlook, is there’s a huge amount of people who are in fact missing in plain sight but in equal amounts of danger.”

Paison didn’t think the post would get much traction, but the next day “I started getting phone calls from people literally across the country who have lost relatives who are on the streets in Colorado,” she says. “All of them are family members that contacted me. I’ve had grandparents, mothers, fathers, sisters, children of missing people who are experiencing homelessness out here. I was not expecting when I started the program for it to take off the way it did.”

Get Home Safely’s first client was a woman from Washington state who asked Paison to find her son, Timothy, who’d last been seen in Aurora almost a year earlier.

Timothy’s mother said she had tried to call the Aurora Police Department “probably nine times in the last three days before she called me,” Paison says.

When she contacted the APD to take a report, “they flat-out told me, ‘We’re not taking one. He’s not missing; he’s just homeless,'” Timothy’s mother says she was told.

She cited the Colorado statute that requires law enforcement to take a missing person report if presented with credible information. “It doesn’t matter, we’re not taking it,” she recalls.

“No wonder this mom is calling me in tears,” Paison says.

Paison emailed then-Aurora Police Chief Vanessa Wilson directly, who responded almost immediately, “horrified that her officers had been such jerks,” Paison says.

Within five hours of receiving Wilson’s response, the APD had taken a missing persons report from Paison and Timothy’s mother. By the next morning, Paison had found him by herself.

Timothy was sitting by an empty creek at Sixth Avenue and Sable Boulevard, about a mile north of Aurora’s city center. He was surrounded by tents, and the area was filled with trash.

Timothy’s case “is a good example of law enforcement apathy when it comes to these cases,” says Paison. “Law enforcement thinks if someone is homeless, they can’t be missing. But obviously, the people that are coming to me, they’re missing to someone.”

Asked by Westword about the APD’s policy on missing persons reports, spokesperson Sydney Edwards says: “If someone believes their friend or loved one who is unhoused is missing and is endangered or possibly involved in a crime, they should reach out to the Aurora Police Department and file a report.”

But as Paison has learned, a big part of her work is confronting law enforcement with a forcefulness that worried families might be reluctant to use.

“It can be heartbreaking to hear from families looking for loved ones on the street.”

Going to organizations that help the homeless can also be a dead end for families, because those groups want to keep information confidential. “It can be heartbreaking to hear from families looking for loved ones on the streets, but without consent from a client, we can’t share anything or confirm if we know the person,” says Cathy Alderman, spokesperson for the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless, one of the largest nonprofit housing agencies and service providers for the homeless in the state.

“We get inquiries about specific people frequently, and we also get missing persons fliers sent our way,” she adds. “We share them with front-line staff, and if we know or find the person, all we can do is pass along the contact information for whoever is looking for them.”

CCH’s policy is meant to protect people from “an abusive partner or a trafficker, or someone estranged for other serious reasons,” but clients might also shy away from coming forward because of “severe mental illness,” Alderman says. “Sometimes it’s simple shame and a desire for privacy that makes people experiencing homelessness not want to be found by family in their current situation.”

According to the Colorado Bureau of Investigation, which held a missing persons event on Saturday, August 5, out of 1,282 active missing persons cases in Colorado, nearly 600 involve people who have been missing in this state for at least a year. And that number only includes the people who have been successfully reported as missing.

There are no estimates for how many of those who are missing might be homeless. According to the most recent Point in Time count, 9,065 people were experiencing homelessness in the metro area one night in January 2023 – a 32 percent rise over the count in 2022.

By the time Lindsey Paison got the call, Sue Sanders had committed suicide.

Sue Sanders

Eighteen months after starting Get Home Safely, Paison has taken on close to two dozen cases ranging from Pueblo to Colorado Springs to Commerce City, but most have been in metro Denver. People have called her from Washington, Tennessee, Virginia, Texas, Missouri and Florida to look for loved ones on the streets of Colorado. While her work has been largely successful, her definition of success has changed over that time.

“If you’re measuring it on how many people have I saved and sent back home, the answer would be two, out of close to 24 that I’ve located,” she says. “But in all of the ones that I’ve been able to contact, if you measure success in at least giving my clients that peace of mind that their son or their mother or their sister is out there and they’re okay but they don’t wish to have contact with their family or they want to stay out on the streets, you know that. … They’re adults, that’s their decision, but it at least gives my clients that peace of mind.”

Only once has Paison learned that a loved one she was hired to find had already died.

After trying to pull herself out of homelessness for five years, Sue Sanders had finally given up when she was forced out of the motel where she was staying because it violated a Greenwood Village ordinance. By the time two of her friends reached out to Paison, Sanders had already taken her own life; her body was found in her car in a Centennial parking lot.

With time, Paison says, her job has “started feeling a lot less like a trying to find a needle in a haystack.”

When hunting for missing people, her primary strategy is to go from encampment to encampment, asking people if they’ve seen the person she’s looking for. She usually hands out a flier with a photo.

“The homeless community, they’re usually very helpful and very cooperative if they can be,” she says. “I’ve always been amazed how receptive people in the homeless community are.”

She often hangs other fliers around downtown, at light-rail stations and places that provide services to the homeless. A handful of cases have been solved when people recognize the person in the flier – or they are that person. A transit security guard once saw one of her fliers and “pointed me in the right direction,” she recalls.

At a P.I. conference, Paison told a group of friends about Get Home Safely, and they laughed. “They all looked at me like I’m out of my mind,” she says. “They laughed and told me that I can’t take these cases for free.”

But she does.

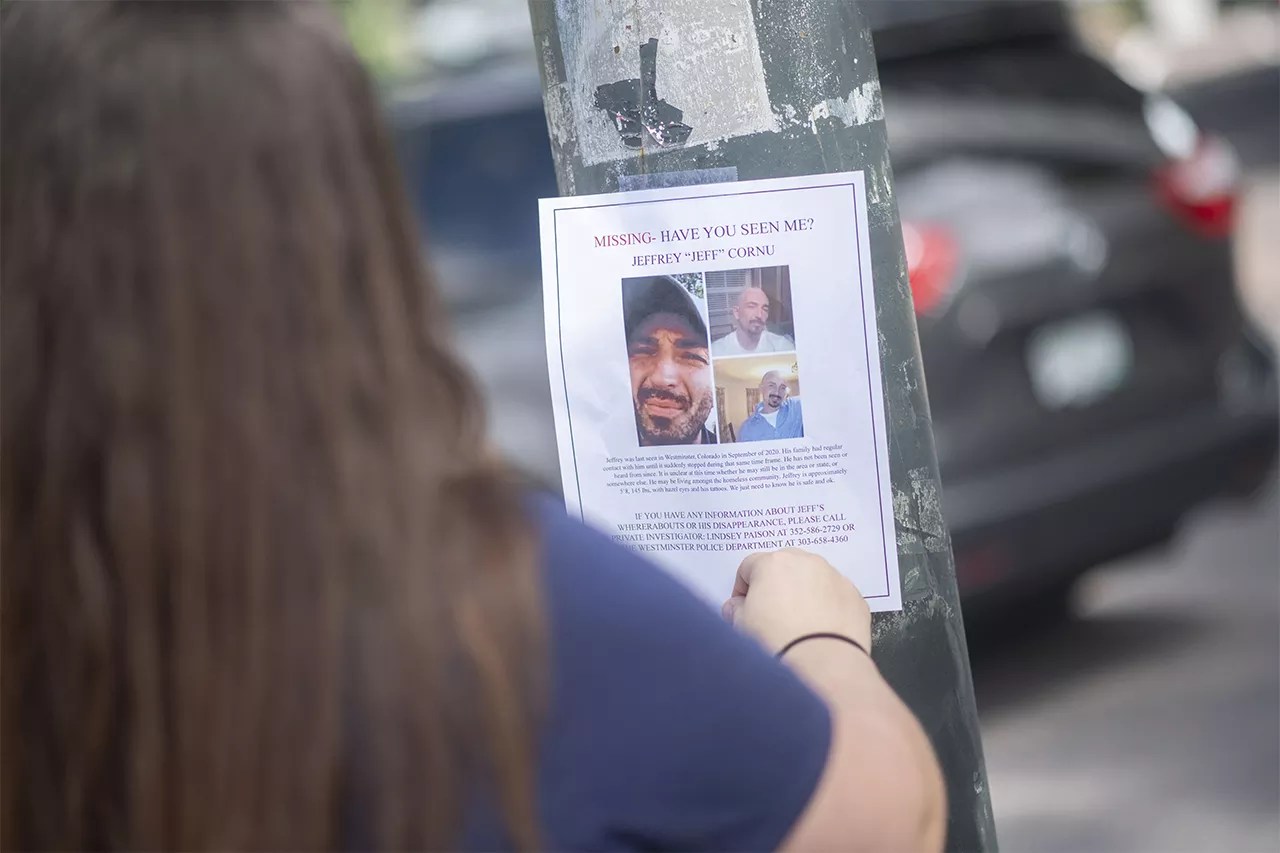

One of Paison’s current searches is for Jeff Cornu, a 38-year-old Westminster man whose family lost track of him when he started living on the streets in 2020.

On a warm July morning, Paison weaved through encampments at Park Avenue West and Stout Street, handing out fliers with Cornu’s picture and information. “He was last seen on Sept. 12, 2020, White Male, 5’8” and 140 pounds, Black, shaved hair,” the flier reads.

“Circumstances: Possibly with the Homeless Population. Does not have his needed medications,” it adds at the bottom.

People were sitting on lawn chairs or on the ground near the tents that lined the streets. Paison greeted each one the same way. “Hey, how are you? Does this guy look familiar in this area at all?” she said, handing them a flier. “He’s not in trouble; he’s just missing.”

Paison was dressed down, in a dark-blue T-shirt, black pants and black boots, because “I’m trying not to give off cop vibes,” she explains. “If they think you’re a cop, they’ll just shake their head. They don’t want anything to do with you, because they’re worried they might get in trouble.”

She dropped off extra fliers, but knows it’s unlikely they’ll get passed around, much less acted on. “After you’ve done it for so long, usually you can kind of tell whether or not the tip is legitimate,” she says.

One of the people who said they recognized Cornu was a woman in a long white wig who barely looked at his picture. Another said he looked familiar, and asked how long he’d been missing.

“Several years,” Paison said.

“Several years?”

“Several years,” she repeated. “But he was homeless when he went missing, so it’s hard to say. Don’t forget to call me if you see him.”

Homeless encampments have popped up in Aurora and other suburbs.

Bennito Kelty

For months after she found Anthony, Paison would cruise by the park where she’d spotted him, keeping an eye out for him. Finally, six months after she’d located him, she saw him sitting on the ground at Cushing Park. “He was in ten times worse shape than the last time I saw him,” she recalls.

She gave him another copy of her card and told him that his sisters were still worried about him.

The next morning, Paison ran into Anthony again, now sitting outside of a cafe that gives out breakfast in the Englewood area. He handed her his phone and asked if she could fix it so that he could connect to wi-fi and call his sisters. She tried, then gave him $5 to buy some water and told him to be sure to keep in touch with Evie and Teresa. “They’re very worried,” she said.

She hasn’t seen him since.