Getty Images/Westword Photo Illustration

Audio By Carbonatix

Jared Stoots knew it was a little nuts to be spending another afternoon sitting in his car, an unassuming SUV parked near the northeast corner of 26th and Larimer streets, covertly watching the foot traffic near a row of townhomes about 100 yards away.

“Oh! Oh!” Stoots exclaimed, spotting a lone figure meandering down the sidewalk. “Is that him? Is that him?” Usually these solo stakeouts didn’t amount to anything, just more hours spent staring at a front door that never opened. But even from a distance, Stoots knew this was his guy. “I mean, I’ve known him forever,” Stoots recalled later. “I recognize his walk. I recognize his mannerisms, everything.”

A 39-year-old real estate broker, Stoots has an affable, laid-back temperament that’s perfect for winning clients and making friends, but not so well-suited for this kind of DIY detective work. Hands shaking with excitement, he nearly dropped his phone trying to pull up the Denver Police Department‘s non-emergency number. When a dispatcher answered, Stoots explained that he had eyeballs on a man with an active felony arrest warrant and needed an officer sent right away to apprehend the individual.

The name? “Jason Lobins,” Stoots replied. “I see him right now, walking north down the street.” He provided more information while pulling the car forward to keep sight of the tall, broad-shouldered man headed toward Joe’s Liquors.

Then the dispatcher asked the inevitable question. Was Stoots with law enforcement? “No,” he answered. “I’m the victim.”

“Please hold.” Eventually, the dispatcher returned and declared, unconvincingly, that an officer was on the way. In the meantime, Lobins had strolled down the street, case of beer in hand, and right back through the door of the three-story townhome where he’d lived and worked since the years when he was Stoots’s trusted wealth manager, financial broker and friend.

A military veteran and advocate, Lobins was a regular in the restaurants and bars of RiNo. For the past decade in Denver, the 46-year-old had operated as an independent real estate developer and proprietor of Lobins Wealth Management LLC, through which he oversaw various investment funds on behalf of clients.

Stoots was among several friends and business associates who’d entrusted their savings to Lobins – only to see them disappear.

For almost three years, Stoots had been trying to compel authorities to hold Lobins accountable. “I’ve called the police so many times,” he said. “Originally, they were telling me to keep my distance, but nothing was getting done. So I was like, ‘Well, if you guys aren’t doing anything, I’m gonna start getting out there.'”

Jared Stoots looking up Larimer Street at the townhouse where Jason Lobins lives.

Evan Semón

I’d known Stoots many years ago, as an extremely talented sponsored skateboarder in the local scene. But I’d barely spoken with him for about a decade when he called me out of the blue. “This is probably going to sound a little crazy,” he cautioned. His story certainly sounded complicated, but a trip to the Denver courthouse to look up legal cases made things clearer, with more details coming from documentation from state agencies, as well as emails, text messages and copies of agreements provided by victims.

In early 2021, state securities investigators found that Lobins had not been operating his business legitimately. Stoots then won a subsequent lawsuit against Lobins Wealth Management, with a Denver District Court judge awarding him a whopping $518,168 for his losses and damages in May 2021. Evidence showing Lobins mishandling and spending investor money had prompted the Denver District Attorney’s Office to file criminal charges against him for multiple felonies in January 2022, when a warrant was issued for his arrest.

Even so, when Stoots reached out to me, more than a year had passed since that warrant had been issued, and Lobins was still on the loose. It’s not like he was in hiding, either. For twelve months, Stoots had been repeatedly telling investigators that Lobins was living and working out of the same house on Larimer Street where he’d always been. Could a businessperson in Denver completely ignore accumulating court cases and a felony arrest warrant for over a year and just continue to live his best life? That’s what seemed a little crazy.

But through multiple interviews and public documents, a story emerges of a man involved in some truly innovative feats of gaslighting, storytelling and fabrication. At various points, Lobins claimed that he was undergoing cancer treatment, manufactured a fake IRS “money laundering” investigation, and manipulated his own friends in order to maintain the ruse.

And it all started where it ended, on Larimer Street.

Jason Lobins posted a photo with Jared Stoots on his Facebook page, when they were still friendly.

Jason Lobins Facebook

In 2013, Stoots was pushing his daughter on an infant bicycle along Larimer when he saw a man standing outside a townhome with a cigarette and coffee. They struck up a conversation, and Stoots learned that Jason Lobins was a real estate developer who had just moved to Denver from Austin.

Stoots had been working at El Diablo when the restaurant shut down unexpectedly, leaving him unemployed. He was living in an income-restricted apartment on Larimer that he shared with a roommate. It was so small that his daughter, for whom he had recently won shared custody, slept in a crib at the foot of his bed. Stoots knew that he had to make a lifestyle change, and was about to take the exam to get his real estate license.

Asked what he did for a living, Lobins replied that he was “retired.” The implication was that he was wealthy.

At first glance, Lobins looked like a prototypical Denver bohemian with a ZZ Top-length beard and an outdoorsy style. But his semi-formal speech and mannerisms, owing to his years in the military, set him apart amid the urban creative-class circles.

Lobins had grown up in the Phoenix area; shortly after he graduated from college, 9/11 hit and he enlisted in the military. He served as an Army Ranger in several deployments in Afghanistan and Iraq. He left the military in his mid-thirties, but being a veteran continued to be a core part of his identity.

He’d just started the support group Help Out Not Hand Outs after hearing about a veteran who was almost homeless; the organization’s mission was to provide non-financial support and aid, and act as a liaison for military veterans in need. In 2013, the group received $22,500 in donations, and Lobins claimed that 97 cents of every dollar donated went straight to helping Colorado veterans. (The nonprofit was eventually dissolved in 2015.) Lobins also served on the boards of other nonprofits, helped set up veterans’ resource centers, and was involved in mentoring veterans who found themselves wrapped up in the Douglas County judicial system. Stoots was impressed.

After Stoots got his real estate license, he began showing Lobins residential properties that he could potentially buy and flip, or maybe pop the top and remodel. Eventually, Stoots brokered the purchase of two homes for Lobins, who paid with cash each time. Their friendship grew to an almost brother-like closeness. Lobins and Stoots would talk with each other almost every day, sometimes multiple times a day. Lobins had a daughter with his then-girlfriend; fatherhood was another commonality they bonded over. They lived so close to each other that it was easy to grab coffee or lunch.

As the years passed, Stoots’s career flourished, and he earned several awards from the real estate brokerage where he worked for total units sold. Lobins offered to bring him in on certain investments.

In 2019, Lobins told Stoots that he had gotten his SEC licensing and had been granted approval to start a “wealth management fund” exclusively for his friends and family members. Other investors were putting hundreds of thousands of dollars into Lobins Wealth Management, he said, while offering Stoots an opportunity to get in on the deal. Stoots agreed to make an initial $25,000 investment and signed a Limited Partnership Private Equity Fund Agreement with Lobins, which projected a 28 percent annual return.

With the real estate market booming, Stoots was incredibly busy. After he collected seven real estate brokerage commission checks worth approximately $81,000, his accountant advised him to establish a business entity with a bank account for tax purposes before the checks expired. In the meantime, Lobins offered to hold the money in the Lobins Group LLC, and they signed a promissory note that Lobins would repay Stoots within ten days. But when Stoots called about getting the money, Lobins initially said a wire transfer had failed because of a bank error. Later, he claimed that the U.S. Treasury had frozen his bank accounts because of a money-laundering accusation related to the third-party checks.

“I’m like, ‘Nobody’s called me from my bank, nothing,'” Stoots recalls telling Lobins. “‘This doesn’t really add up. Like, what’s going on?'”

But Stoots still thought that Lobins was worth millions of dollars, and says he felt bad bothering his friend about the situation. After all, Lobins asserted that his lawyers and assistants were going after these banks, and that they were “gonna unfreeze my money.” In a subsequent text message, though, Lobins wrote that the “banking is still fucked up…I’ll hit you up and fill you in on the workaround for sending you $81k this week. I got a plan B and C working right now.”

Stoots remembers thinking: “This guy’s got so much to lose, he’s worth so much money, how could this not be legit? Why would I doubt this?”

Jared Stoots haunted Larimer for a sighting of Jason Lobins.

Evan Semón

Stoots was still sitting in his car on Larimer Street, waiting for the freaking cops to come. Hours had passed. He’d called police dispatch for an ETA. He’d phoned the point of contact he’d been given at the DPD, who was assigned to the case. Eventually, he got a call back from an officer.

“They basically said, ‘Yeah, we’re not going to come,'” Stoots recalled. “I mean, I don’t know why they won’t just knock on his door, but he’s like, ‘Well, you both know what’s gonna happen. He’s gonna see us in uniform. He’s not gonna answer.’ I’m like, ‘Well, can’t we get clever?’ I mean, obviously, it’s not a priority.”

He’d heard the same story at least a dozen times over the past twelve frustrating months, all while pictures popped up on Lobins’s Instagram feed of him at a Broncos game on January 8 and partying at the National Western Stock Show on January 26.

Stoots was confronting the hard reality that these kinds of cases do not always receive top billing among local law enforcement. Unless the scofflaw is high-profile or there’s some kind of special focus on the case, authorities will often not take action to get the warrant needed to arrest someone inside their home. On any given day, police are dealing with shootings, carjackings, assaults, overdoses, robbery; white-collar crime doesn’t often rise on the priority list. When wealthy and connected people are victims of financial fraud or involved in other disputes, they have the resources to deploy an army of attorneys, private investigators and accountants who understand the complexities of the legal system and eventually pressure the perp to come to justice.

But Stoots was just some guy. To him, trying to navigate the bureaucracy and encountering the inaction of officials was bewildering. It’s not like Lobins had run off to Mexico or was hiding out somewhere. Heck, he was even in the house where he ran his fraudulent business!

By now it was fully dark, and the evening crowds were headed to restaurants and bars – the kinds of places Stoots had sometimes gone with Lobins. All those intimate moments they’d shared as close friends, in life and in business. Was it all an act? All those instances that, in retrospect, were red flags and should have warned Stoots to pull out and save himself. Was Stoots a fool to have ever trusted him?

Sitting in his car, Stoots went back over the period when everything started to fray and go to hell.

In early 2020, Lobins was still sending out his investment newsletter covering topics such as S&P ratings and how Federal Reserve interest rate changes might affect stocks.

That summer, the pandemic and ensuing lockdowns pushed Stoots to look for a way to move out of his cramped apartment.

As he brokered dozens of deals that summer for clients getting their dream homes, Stoots won the bid for his own. The unique, mid-century-style three-bedroom home in the Applewood neighborhood of Wheat Ridge had a large back porch and a backyard with a pond and a fountain. His daughter would finally have a place to play. At $475,000, it was an amazing deal, and he began making arrangements to transfer money for the down payment.

“My daughter and I are going to finally have a house, and we were so excited,” he recalled. Even Lobins got excited when Stoots showed him the pictures. “He said things to me like, ‘Dude, it’s a great house. You’ve come from nothing to this. Congratulations.’ Like, heartful stuff,” Stoots said.

For months, Stoots had been telling Lobins that he was going to need to withdraw money from the funds he’d invested with him to use for a down payment. The updated agreements and other signed documents clearly laid out the details and terms for allowable client withdrawals; the quarterly reports that Lobins had been sending to Stoots showed not only that his money was safe, but that the investment fund overall was going gangbusters. “The reports looked legitimate,” said Stoots. “He was showing me how much money everybody else was making, that he was making.”

Lobins had even sent a screenshot of a Merrill Lynch “One-Time Non-Retirement Distribution Form” to Stoots showing that the Lobins Group LLC was trying to get a distribution of $72,934.18.

Then he got an urgent call from Lobins, asking him to meet him at his house on Larimer. As he sat down in Lobins’s living room, Stoots was surprised by how awful his friend looked, face drawn and serious, with blotches of a rash across his neck and arms. “I was like, ‘You’re freaking me out, dude,'” Stoots recalled. “‘What’s going on? Is everything good?'”

Lobins told him he’d been diagnosed with leukemia and the prognosis wasn’t good. Stoots was shocked. They both cried. It was so overwhelming that Stoots decided it was an inconsiderate moment to be pushing the money issue.

As Stoots progressed on the house purchase, completing inspections and the appraisal, he made arrangements to take his friend to chemotherapy appointments. But each time, Lobins would cancel at the last minute. It was very, very strange. As the deadline approached to make the down payment and close on the house, Stoots became extremely nervous.

Lobins emailed a computer screenshot of an investment account’s statements along with supposed receipts showing the wire transactions, but the money never arrived.

In a text message, Stoots wrote: “Is there a wire receipt or hasn’t been sent yet? I’m not trying to add to everything you’re going through. But my earnest money goes hard on the 4th and if I don’t have the down payment by then, I will need to terminate the contract on the house.”

Lobins replied: “$72,934 was withdrawn on Friday. I don’t see any wire receipt or a confirmation. I’ll get on the horn with Merrill Lynch first thing in the morning. The Denver branch opens at 9:30.”

“Okay, awesome. Thanks, man. Kind of freaking out,” Stoots said.

But the money never came, and instead, Lobins sent a cascading litany of ostensible problems, including the suggestion that the IRS was investigating Stoots for “Schedule C” issues and that he was in big trouble with the agency. But when Stoots called the IRS, he confirmed that there were no such issues.

He lost the house.

Jason Lobins was evading Jared Stoots in person and on social media.

Courtesy of Jared Stoots

“Well, I’m either going to pay you back or I’m going to jail for the rest of my life.”

Lobins’s ex-girlfriend remembers him saying that more than a dozen times from 2019 to 2022, in reference to nearly $200,000 that she had placed in his care. (Since she is the victim in a domestic-violence assault case involving Lobins, I’m withholding her real name and calling her Katie.)

Katie had met Lobins in California around 2017 through a friend who was an old Army buddy of his. Her initial perception of Lobins was of a physically large man, charismatic, with an earnest demeanor. “He’s very articulate in the way he speaks. He seems to have a great understanding of how to speak and adapt in social situations with other people and speak to them on their level,” she says.

At first they were just friends. “He will talk about things that make him seem vulnerable.” Katie says. “He sort of acted as a confidant for me during that time.” But then they started dating, and soon they were living together in a rented apartment in Marina del Rey. Lobins would split his time between there and Denver.

In 2018, Katie suddenly had a lot of extra money come in, and she was trying to figure out how to invest it. Lobins said he was getting back into that business and that a lawyer friend had “these deals falling into his lap”; they could really capitalize on them, as they were “very simple investments that have very quick return.”

Lobins brought up a real estate development with an initial investment of just $30,000; he said she would get an additional $6,000 back within the month. And she did. “So, of course, that was like the baby step into it that made me feel comfortable. Then the following requests were for, like, larger and larger amounts of money,” she recalls. “Basically, that was like that was the bait.”

Throughout the next year, Lobins suggested other investments. Currently a residential real estate agent, Katie had a background in commercial real estate at the time; Lobins showed her all the documents and discussed the various filings. “He could answer sort of every question I had,” she says.

Then he wanted her to invest in his wealth fund. “He basically pitched it as like, he’s been so smart with money, and all he wants to do is make his friends and family money, it was personal, and I’m doing it for my kids,” Katie recalls, adding that he showed her charts of how the growth would happen and all the other investors putting in cash.

In early 2020, Lobins left California to come back to Denver to close a real estate transaction in which Katie had invested $100,000. “He said he was going home to do that, to close that, and boom, I was gonna get my money,” she says. But first, Lobins asked for $22,215 for “unrealized tax gains” related to her initial investment. She sent him the money.

Then the country locked down because of the pandemic. Katie talked daily with Lobins. He told her he couldn’t wire money back to her because his accounts had been frozen as a result of Stoots’s difficulties with the IRS. As Katie kept asking Lobins about initiating withdrawals, he dropped the news that he had cancer. As the months passed, their conversations “started to get super weird and shady,” she recalls, but she stopped talking about money because she wanted to be supportive while Lobins underwent treatment.

One day Katie texted, “Hey love! Did you go to the banks today to sort things out?”

“Great timing. I’m here now,” Lobins texted back. “Getting you reset and dealing with a Jared issue from Merrill Lynch.”

But it never did get sorted out. The vague reasons and excuses “just kept on going, going and going like that,” she says. “I was like, something’s wrong. But basically, I just went into full denial. Because he left and never came back. He has a lot of my money. Says he has cancer, but won’t let me see him. And I felt stupid, like, okay, what is happening right now?”

Katie had met Stoots on her previous visits to Denver, but she’d never talked to him about her financial dealings. Finally, they had a phone conversation in late October 2020. Katie recalls: “He was like, ‘Hey does Jay owe you a bunch of money?'”

Courtesy of Jared Stoots

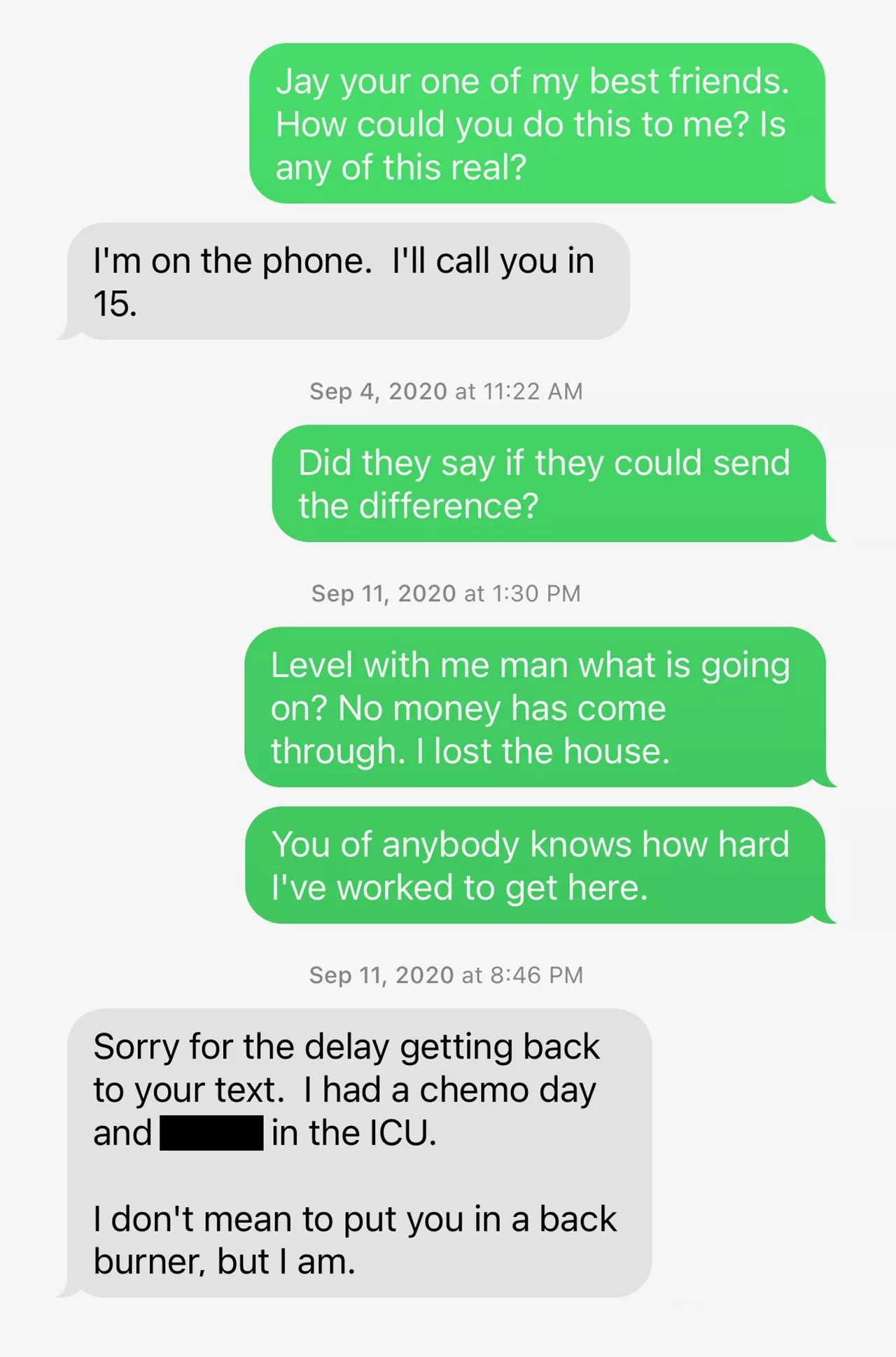

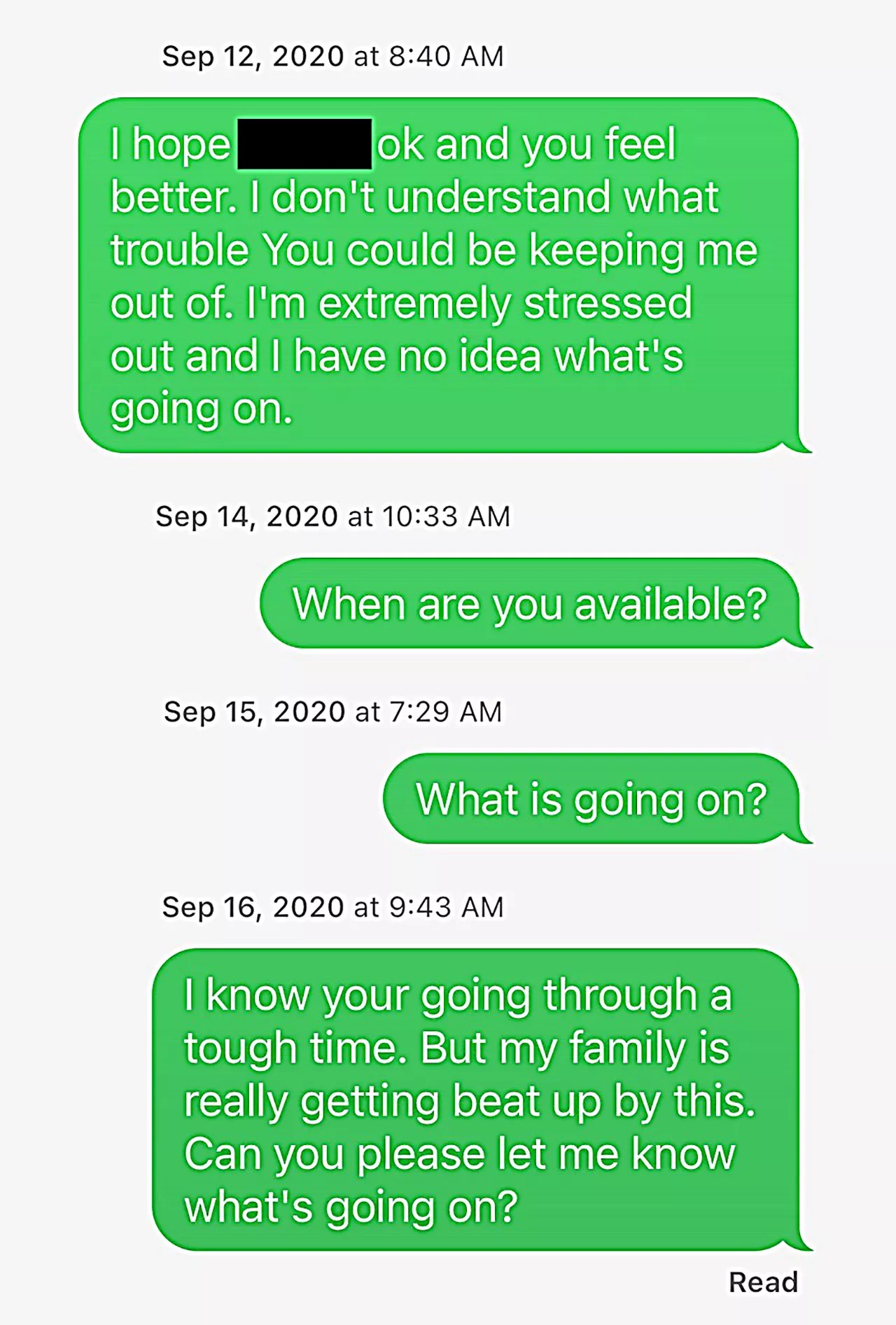

Still staking out his man, Stoots sat in his car parked on Larimer and read out the last text exchange he’d had with Lobins.

Stoots: “I don’t know if you’re mad at me or what’s going on man but I’m really concerned I’m gonna lose the house. My bank is saying ACH transfers only take 1-2 business days. And they would see if it attempted to come through. Can you please check on it?

Stoots: “Jay, you’re one of my best friends. How can you do this to me? Is any of this real?”

Lobins: “I’m on the phone. I’ll call you in 15.”

Stoots: “Level with me, man. What is going on? No money has come through. I lost the house. You of anybody knows how hard I’ve worked to get here.”

Lobins: “Sorry for the delay getting back to your text. I had a chemo day. … I don’t mean to put you in a back burner but I am. We have a lot to discuss. I’m working on a plan to get you all of your money back from the cashed checks to the investments gotta jump through a few hula hoops to keep you out of trouble. Let’s link up Monday.”

Stoots: “I hope you feel better. I don’t understand what trouble you could be keeping me out of. I’m extremely stressed out and I have no idea what’s going on.”

No response.

Stoots: “I know you’re going through a tough time. But my family is really getting beat up by this. Can you please let me know what’s going on?”

From that moment on, Lobins stopped responding to Stoots. Knocks on his door went unanswered.

By now, officials with the Colorado Division of Securities had been looking into Lobins Wealth Management, prompted by a complaint submitted by Stoots. Investigators attempted to reach Lobins through multiple emails, letters and voicemails but got no response. It turned out that Lobins was never registered with the SEC as an investment advisor, nor were he or his company approved to function as “securities brokers,” as required by law. In late 2020, state agents filed subpoenas to allow investigators access to his accounts.

According to an affidavit filed in Denver District Court, an investigative audit of Lobins Wealth Management financials showed that Lobins had deposited around $270,000 of the funds into his personal bank accounts.

“The outflow analysis shows Mr. Lobins used the vast majority, at least 98%, of the funds solicited from Mr. Stoots, [Katie] and one other investor for his personal benefit,” states the affidavit. “Mr. Lobins’ use of these funds include transfers to his personal trading accounts at Merrill Lynch, TD Ameritrade, and Robinhood, transfers to his personal checking account at Bank of America, rent payment obligations, payment of personal credit cards, payments to other investors, and payments to the mother of his child.”

Investigators also looked into the account statements and screenshots sent by Lobins to Stoots that purported to show his investments were sound and stable. They looked up the number of one Merrill Lynch investment account and “learned the account was not owned by Lobins.”

Meanwhile, records indicate that Lobins Wealth Management was granted a $20,833 PPE loan as part of the pandemic relief program, with Lobins listing his business as “Offices of Real Estate Agents and Brokers.”

Stoots hired an attorney and filed a lawsuit against Lobins in Denver District Court on December 28, 2020, alleging breach of contract, breach of fiduciary duty, deceit based on fraud, and civil theft related to the investments and a promissory note. Stoots was represented by Lindsey Brown, an attorney with Milgrom & Daskam. According to Brown, Lobins was served with the complaint, which had a summary of all the facts as well as the charges, “so he was aware of what was going on.”

After Lobins failed to respond to any of the pleadings, in May 2021 a judge issued a default judgment in favor of Stoots for $518,168, which covered the principal he’d lost, plus interest and damages.

While the eye-popping award was a victory, it was a hollow one. Typically, victims are able to recoup compensation by requiring the defendant to fill out financial questionnaires and filing writs to garnish wages or other assets. “But we weren’t able to serve [Lobins] those documents because he’s avoiding service, in my opinion,” Brown says. Attempts to look into some of Lobins’s known bank accounts “turned up empty, so we haven’t yet been able to collect.”

The strategy of simply not showing up – the most basic form of avoidance – seemed to be working just fine for Lobins.

“I don’t know that this was his whole plan the whole time,” Stoots says. “I think about that often. Part of me thinks he thought he was actually gonna be able to return everybody a profit, but just wasn’t being transparent on how, and he didn’t really have an exit strategy or escape plan.”

And another part of him was just in shock. “In the beginning, it felt like I failed my daughter,” Stoots says. “I couldn’t even tell my dad. I’d just be like, ‘Dude, you’re an idiot. You’re an idiot.’ And I was just beating myself up every day.”

Living on Larimer Street, he’d walk past Lobins’s home every day, look in the windows and try to make sense of what happened. “I went to therapy for a long time,” he says. “It was a huge point of contention in the relationship I was in with my girlfriend at the time. Just ’cause, you know, I probably wasn’t my best self.”

In early 2022, it seemed like progress was finally being made when the Denver District Attorney’s Office filed criminal charges against Lobins for two counts of securities fraud and two counts of theft over $100,000; a warrant was filed for his arrest. With four felony charges, Lobins could be facing years in prison if convicted.

But first, he had to be arrested.

Stoots had finally saved up enough money to buy a home, this time in Westminster, but he still found himself making pilgrimages down to Larimer to see if he could catch Lobins walking about. To see if he could get the cops to respond.

The cops finally caught up with Jason Lobins here.

Kristin Pazulski

On February 22, 2023, during an evening snowstorm that made Denver’s roads hard to navigate, a team of six Denver police officers entered the Walnut Room. Everyone in the crowded venue, located just one bloc k off Larimer, took notice. This included Lobins and a group of his friends, many of whom happen to be lawyers, who were hanging out around the virtual golf game. Lobins noticed that the cops were wearing tactical gear, as if ready to apprehend a dangerous fugitive.

Earlier that day, Katie had gotten an unexpected phone call from Lobins; they hadn’t talked in a long time. After Lobins casually mentioned that he was heading over to the Walnut Room to celebrate his birthday, Katie passed the intel to Stoots. He rushed down to RiNo and recruited a friend to scope out the bar: Lobins was there.

Stoots called the cops. And this time, they actually showed up. He could hardly believe it.

Even more surprised was Lobins. He was thrown to the ground by the cops, handcuffed and hauled away to Denver County Jail, where he was booked on four felony counts.

After a few days waiting in lockup, Lobins was able to see a judge and gain release on bond.

For more than a month, I’d been sending emails and leaving messages, asking Lobins for an interview; I’d never gotten a response. But then he called.

The conversation began with Lobins saying that he had “no comment.” His attorney had explicitly instructed him to not speak to any reporter, he said.

“I’m actually going against counsel advice,” he continued, his voice distraught. “I’m six-foot-two, 210 pounds – very big beard, full-size man, used to be an Army Ranger – and, yeah, I’m crying.”

He was “mortified” and “heartbroken” by his arrest and the circumstances that precipitated it: “While I’m being accused of being a piece of shit, I’m not,” he said.

That was the start of an hour-long conversation in which Lobins frequently interrupted himself with apologies for being overcome with emotion and admonishments to himself for talking. “Oh, God, my lawyer’s going to fucking hate me for doing this,” he admitted.

But he kept talking. “I lost my best friend on this,” he said at one point. “Oh, God, I have to shut up.” A pause.

He kept talking.

What was his explanation for the missing wealth fund money? His lack of proper licensing? The shifting explanations for not returning investments?

Using the words “misunderstanding” and “other circumstances,” Lobins asserted that evidence would be “coming out in court” that he couldn’t share right now.

“I will say this. I did not solicit anybody,” he added. “I was asked. Both the victims asked me to deploy their finances. It was not me soliciting. I was not goddamn Bernie Madoff, man. Like, I’m not.”

He said he feared the possibility that people might think of him as a scammer; that flew in the face of how he wanted the world to see him. In the military, one of his jobs was as a sniper. “And people always think it’s cool, like you shoot somebody in the face,” he noted. “Like, nope. Actually, most of the time we’re doing overwatch, protecting. Protecting ground troops. I still live that way.”

It was in the military that Lobins first got into investing on behalf of other people, he said. He recalled being in a tent in Afghanistan and helping fellow soldiers use sites like ShareBuilder to invest small amounts: “You put up $20 a month in the S&P 500, let wealth build, dollar/cost average. Like, I’ve always tried to make other people better.”

He still had an urge to serve people and protect them. That’s how he characterized his investment funds, as a way to aid people like Stoots by helping them earn more and provide security. But he was no longer doing investment fund work for people, because all of his accounts had been frozen and he was cut off from his bank accounts and credit cards.

Why hadn’t he responded to legal actions? He pleaded ignorance.

“I didn’t know somebody tried to sue me. I didn’t know there was a lawsuit. I just found out that I owe $500,000 now,” he said of the civil lawsuit Stoots vs. Lobins filed in Denver District Court in December 2020. “Nothing came by mail, by phone.” Asked about the record showing that he was officially served, he then acknowledged, “Actually, I did get served. Yes. And then I was waiting for a court date. Which never came.”

He claimed that he was similarly oblivious to the investigation by the Colorado Division of Securities. He knew that a complaint had been filed, but “I was told it was dismissed,” he said. In fact, investigators had concluded the case warranted referral to the Denver DA’s office in November 2021.

Even the fact that there was an arrest warrant in his name was a huge surprise, he said: “They could have mailed it. They could have handed it to me. I would have turned myself in had I known about it. No, no, sir. I had no idea. I got blindsided.”

But there was one bright spot. “It turns out I didn’t have cancer,” he said. That was just the result of a big “confusion” over treatment for a condition he described as an undiagnosed “autoimmune issue.”

Lobins has a court date on March 16, when he is scheduled to be formally charged. “Which is big. That’s huge,” he said. Katie and Stoots wonder if he will show up. They wonder why the judge let Lobins out at all when he could be locked up for a long time.

“That’s 48 years in prison,” Lobins acknowledged. “So, yeah, that’s not where I’m trying to end up. And if I do? Well, sure. Maybe I made mistakes. Maybe I fucked up. You know, we’ll see if we get that far. Either things get dismissed, or a jury tries my fate.

“And after that, like, yeah, man, I’ll be able to talk about what happens when your friends turn against you.”