Feverpitched/iStock

Audio By Carbonatix

It’s Open Mic Night at Loonees Comedy Corner, a nightclub on the east side of Colorado Springs. Two dozen aspiring comedians are milling around the bar, waiting for the show to start. The atmosphere is casual and chatty; the sparse crowd consists mostly of the performers and their friends.

Richard Boccardi sits apart from the others at one end of the bar, nursing a beer and chatting up no one. A large man in his late forties, fit and heavily tattooed, Boccardi doesn’t seem nervous about his upcoming turn on stage. But there’s a coiled tension in his posture, a sense of detachment, like a kick returner sitting by himself in the locker room a few minutes before kickoff, alone with his thoughts.

As people start heading into the club, Boccardi nods at a couple of other veterans of open-mic nights. He confides that he’s working on new material. “I’m going to try something different tonight,” he says. “Something about prison. It might bomb.”

For someone with Boccardi’s background, standup comedy might seem like an odd pursuit. There’s nothing particularly funny about the fifteen years he spent behind bars, comprising approximately half of his adult life. Not too many yuks in the fact that nearly a decade of his prison time was spent in solitary confinement. Among other long-term effects, his experience of isolation has led to bouts of agoraphobia, days when it’s difficult for him to leave his house, even to step outside for a smoke.

But that’s precisely what has drawn him to performing. Boccardi has been in some harrowing situations over the years, from the prodigious drug use and other reckless behavior of his youth to mixing it up with hard-core gang members in prison. He held his mud while prison officials tried to convict him of a cell-house murder, despite substantial evidence of his innocence. He’s fought testicular cancer and depression so severe that it made him suicidal. He’s been diagnosed as bipolar, enduring years of failed treatment plans before finding the right medication to help manage his condition. Yet nothing in his battle-scarred existence compares to the exhilaration, the terror, the sheer thrill of getting on stage and trying to make a bunch of strangers laugh.

“I’ve done it maybe six times now,” Boccardi says. “I have so much stuff in my head that I want to use, but you have to shape it and work it. I’m trying to find a way to use what I went through in prison without freaking people out.”

“I’m a throwaway person. People see your past, and that’s all they see.”

What Boccardi went through in prison and on parole is instructive on several levels. After years of a declining incarceration rate, Colorado lawmakers are bracing for a projected 20 percent hike in the inmate population in coming years, with state prisons now at 99 percent capacity. The increase has been driven in part by growth across the state, but also by the high recidivism rate, which has hovered stubbornly around 50 percent for years despite increased emphasis on re-entry programs. Out of the 10,000 felons on parole in the state on any given day, half of them will be back in prison for a parole violation or a new crime within three years – an intransigent core of repeat offenders that has become a major factor in the state’s soaring prison budget.

For many years, Boccardi was one of those caught in the revolving door. He would be released from a high-security cell to the street, land in trouble, and be on his way back in no time. Part of that, he readily admits, was his own attitude, a convict mentality that amounted to self-sabotage. But part of it, he insists, had to do with the obstacles ex-offenders face when seeking jobs and housing, and the ways that the system seems designed to perpetuate failure.

“I’m a throwaway person,” Boccardi says. “People see your past, and that’s all they see. That matters a lot more to them than whatever changes you’ve made. But I try not to let that get to me. I get up every day and do what I need to do.”

Boccardi eventually stopped doing the things that were sending him back to prison. Although he still struggles at times with the stigma associated with having a prison record, he’s been out more than a decade now and doesn’t believe he will ever go back. His journey may have the makings of dark comedy, but it’s also a playbook of sorts for those trying to break the cycle of recidivism.

As he heads up on stage, Boccardi is still mulling over the new material. He has three minutes to win the crowd’s love, and it’s entirely possible that he will bomb. But it will be worth it, he figures, if he can get just a few good laughs.

After years of being stuck in the correction system’s revolving door, Richard Boccardi is looking to have the last laugh.

Anthony Camera

Even at an early age, Boccardi knew he was different from other kids. He was exceptionally hyperactive, defiant of authority, and frequently at odds with his parents, his teachers and his classmates.

“Some of it was acting out from the way other kids treated me,” he says now. “I remember kids telling me that their parents thought I was weird and didn’t want them to hang out with me. That’s hard to comprehend when you’re ten.”

Boccardi was born in Germany in 1970, the youngest son of a U.S. Army helicopter pilot. The family moved to Colorado Springs when Rick was in the second grade. He was bullied at school, unfocused and so prone to trouble that his parents took him to see a psychiatrist. For several years, as he moved from suspension to expulsion to a fresh start at yet another school, his parents and his doctors believed that his behavior stemmed from an attention deficit disorder.

At fourteen, Boccardi was sent to a psychiatric center in Texas for several months. He returned determined not to be bullied anymore – and picked up his first felony after taking a gun, his grandmother’s derringer, to school. “I’m really ashamed I did that,” he says. “At that point I hadn’t been diagnosed and wasn’t on medication. But I did things that were impulsive and selfish, and that’s what this was. I pulled this gun on a kid on a city bus.”

The gun wasn’t loaded. Boccardi got kicked out of school again and placed on probation. At seventeen he was diagnosed as bipolar. He was put on various medications with powerful side effects.

“They were giving him lithium, some really heavy-duty drugs, just cramming it down him,” recalls Larry Roberts, an old high school buddy of Boccardi’s. “They were trying to keep him on an even keel, but that stuff was killing him. He would stop taking his meds, we would start partying, and things would get out of control.”

Boccardi says the lithium “shut me down” and caused an eruption of painful boils on his face. He preferred to self-medicate with alcohol, cocaine and meth – a recipe for disaster, he notes, particularly for someone given to manic episodes. He began to steal small amounts of cash or hockable items from his parents. He and Roberts would hang out at heavy-metal concerts, looking for excitement – and usually found it.

Boccardi turned 21 in prison; he spent much of the next decade in solitary confinement.

Courtesy of Richard Boccardi

“We were always in trouble for one thing or another,” recalls Roberts, who now lives in Pennsylvania. “It seemed like bad luck would follow us around. We would always be doing something stupid when the policeman was right behind us. But I never saw the bad side of Rick. I always saw the best friend, the protector. We considered ourselves brothers.”

Boccardi came close to graduating from a last-chance “alternative” high school – but a diploma wasn’t a priority for him then. He spent his eighteenth birthday in county jail after getting kicked out of a drug rehab program. “I was really lost in drugs and partying,” he says. “I didn’t care about anything. I was not a good person for many years. I wasn’t a good son.”

In 1988 Boccardi’s parents moved to Illinois, where his father, long retired from the military, had accepted a new job. Boccardi divided his time between Illinois and friends back in the Springs, picking up charges in both places. He was on probation for criminal mischief in Colorado – he’d thrown a rock through the window of a doughnut shop – when he got arrested for a fire in a motel room he’d rented for a party in Arlington Heights, Illinois. Boccardi says his chief accuser was the actual instigator of that fire, but he ended up taking the rap.

He also stole his father’s credit card, spent freely, cleaned out a bank account and smashed the family car – a rampage that compelled his parents to press charges this time. In 1991 Boccardi pleaded guilty to theft and was sentenced to five years in prison. He turned 21 in the Buena Vista Correctional Facility.

Over his first eighteen months in the Colorado Department of Corrections, Boccardi underwent a startling transformation. He went from being a scared kid to a ripped bodybuilder – 6’4″, 190 pounds, an intimidating presence in his own right. He hung out with skinheads and sported a swastika tattoo, thunderbolts and other ink that seemed intended to provoke. Boccardi says he was more interested in the Nordic religion of Asatru than racial politics, and he apparently had some African-American friends behind bars. But it also seems clear that he was quickly being sucked into affiliations that would lead nowhere good.

“As a kid, he was a little shy, a little insecure,” recalls Kevin Chillis, an ex-offender who first met the teenage Boccardi in county jail. Years later, Chillis, who is black, watched Boccardi being pressured by white gangs in the DOC. “They would come to the white kids and make them give up their paperwork and do whatever they had to do to make them join. Rick was like, ‘I’m not taking orders from anybody.’ But I knew the culture, and I knew people did the things they had to do.”

At Buena Vista, Boccardi got into a fight in the chow hall. Another dispute erupted with a cellmate he suspected of being a snitch. The conflicts led to his transfer to Limon, the most violent prison in the state system. He was there only a few months before he landed in the middle of a murder investigation.

On the morning of April 5, 1993, nineteen-year-old Robert Gardner III was found dead in his cell at Limon. He’d been strangled with an extension cord. The logical suspect was Gardner’s cellie, Tim Starkey, an avowed white separatist, who described Gardner as a “race mixer” and a thief. In statements to prison officials and a journalist, Starkey readily admitted to the deed.

“He woke up, and I started putting an electric cord around his neck,” Starkey told a Westword reporter. “We battled it out for a little bit, and eventually he got exhausted and gave up.”

“We battled it out for a little bit, and eventually he got exhausted and gave up.”

Starkey took a plea deal in the case. But even though he claimed to have acted alone, prison investigators also grilled Boccardi about Gardner’s murder. Boccardi and Starkey had been cellmates and friends at Buena Vista. Boccardi had reportedly had an altercation with Gardner just days before his death. And there was a confidential informant – a cell-house snitch – who claimed to have seen Boccardi enter Gardner’s cell that morning carrying an extension cord.

Boccardi denied any involvement. He lived on a different tier than Starkey, and to get into the cell and strangle Gardner would have required him to defeat a series of locks and avoid detection by staff – not impossible, but not likely, either. (“Their theory was that he died at five o’clock in the morning, before the doors even opened,” Boccardi notes. “I somehow beat the lock on my door and go to Tim’s house on the second tier, and then go back upstairs, and nobody sees or hears me at all.”) He had witnesses who placed him elsewhere at the presumed time of the crime. And, unlike Starkey, he had no cuts or marks on his body that indicated he’d been in a ferocious struggle with the victim.

Hair, blood and prints taken from Boccardi failed to incriminate him. The case against him was so tenuous that the Lincoln County District Attorney’s Office declined to prosecute. But that didn’t stop prison officials from filing charges against him under the Code of Penal Discipline – an administrative procedure with much looser standards of evidence than those of a court of law. In a disciplinary hearing held at Limon, Boccardi wasn’t allowed to call any witnesses on his behalf. He was found guilty of violating the prison code by murdering someone.

As a result of that finding, prison officials could punish Boccardi for a crime that, according to the courts, was committed solely by someone else. He was sent into solitary confinement at the Centennial prison. A few months later, when the DOC opened its new state-of-the-art supermax prison, the Colorado State Penitentiary, Boccardi became one of its first occupants.

He was in lockdown 23 hours a day. The only times he was out of the cell was when he was escorted in shackles to the shower or the exercise room, a closet-sized space with a pull-up bar and a delicate current of air piped in from the outside.

He spent the last three years of his sentence locked down, and many years to come.

With the aid of his service dog, Thirteen, Richard Boccardi has found ways to cope with the emotional legacy of lockdown.

Anthony Camera

For much of its history, what constituted solitary confinement in America varied greatly from prison to prison. Going to the hole could mean moving to a smaller cell with a mattress on the floor, or to a dark, airless room with a hole in the bare concrete and a bucket of water to flush with. It could be a sweatbox or an icebox. In some instances, the cells were so close together and communication between them so easy that it could hardly be considered isolation at all; in others, silence was strictly enforced. In extreme cases, such as the “dungeon” below D Block at Alcatraz, it could be a place where men were stripped and shackled to the wall.

Regardless of the particulars, all these arrangements had a common purpose: They were intended as a form of short-term punishment. Little thought was given to hygiene, medical conditions, mental stimulation or other needs beyond basic sustenance – because nobody was going to be there very long. The punishment was for a day, a few days, perhaps a few weeks at the most. In the classic 1967 prison movie Cool Hand Luke, regarded at the time of its release as an unabashed wallow in sadism and brutality, convicts in need of an attitude adjustment spend a night in the “hot box.” One night. Anything more than that would be cruel and unusual.

The country’s approach to solitary confinement began to change in the last quarter of the twentieth century, as the prison population doubled between 1974 and 1982, from 200,000 to 400,000, and doubled again over the next decade. Many of the new arrivals consisted of nonviolent drug offenders, but the surge also coincided with a rise in prison gang activities, a sharp increase in mentally ill prisoners, and a spike in assaults on staff. By the mid-1980s, several state prison systems were exploring ways to transform their disciplinary units into places where they could stash their most troublesome inmates indefinitely – for months, possibly years. The movement eventually led to the opening in 1989 of California’s Pelican Bay State Prison, one of the first of the modern supermaxes, and the Colorado State Penitentiary four years later.

“I found comfort and solace locked in a cell, crazy as that sounds.”

CSP’s physical design and mode of operation were widely studied and imitated. It was the beginning of a vast experiment in long-term isolation that many corrections officials now regard as counterproductive, and that the last two Colorado prison chiefs have sought to abolish.

As one of the youngest tenants of the new supermax, Boccardi had less experience with life in the hole than many of his neighbors. But he knew enough to start concocting rituals and routines to fend off the nothingness surrounding him. He developed an elaborate exercise regimen. When he wasn’t working out, he was pacing his cell, sometimes for hours at a stretch. And he gradually retreated into a world he created in his head.

He would turn off the television, cover the lights, and sit in the dark. He imagined that he was out of prison and that he’d just won the lottery. He thought about all the things he would buy, the places he’d go, the adventures he’d have. It was like a movie with endless twists and alternate endings.

“I lost my mind for many years,” he says. “I found comfort and solace locked in a cell, crazy as that sounds. You can fantasize your life that way. You get addicted to it.”

No CSP inmates were allowed outside the building unless they were being transported to court or a hospital. The lucky ones had a patch of sky to observe from their narrow window, but in some of the cells the view consisted of a wall of the complex, rising stories above. “They say you’re only allowed to be in one of those [cells] for six months, but I probably spent two years in there,” Boccardi says. “It’s like living in a cave, man. And sometimes you’re happy to get it. Then you don’t have to look out your window. You don’t have freedom in your view out there.”

Despite his best efforts to keep it at bay, the bitter reality of CSP had ways of sneaking into his house. In its early years the prison’s Special Operations Response Team conducted numerous cell extractions – a procedure that begins with a defiant inmate refusing to cuff up or respond to other commands, and inevitably ends with heavily padded SORT members pouring into the cell, armed with stun shields, tasers and pepper spray, to “extract” the non-compliant prisoner. Some prisoners welcomed the combat as a break from the tedium of administrative segregation, even though they were heavily outnumbered and the likelihood of injury was high.

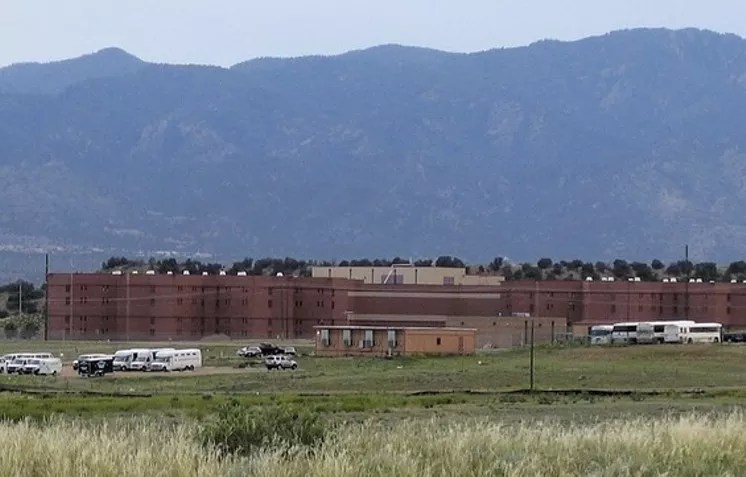

Opened in 1993, the Colorado State Penitentiary was one of the first of a new wave of state supermax prisons.

Rte50.com

Boccardi never went through a cell extraction, but the process took its toll on non-combatants, too. Once discharged, the pepper spray seeped through the ventilation system to other cells, leaving prisoners gasping on the floor and burying their heads in wet towels. It was difficult at such times, Boccardi says, to continue to pretend that you were somewhere else.

The boredom and antagonism of CSP also made it a crucible of what prison officials like to call “security threat groups.” A white gang called the Aryan Syndicate was formed there; Boccardi knew its founding fathers and says it made its followers feel important, since the only way to get into the group was to be in CSP. “This was part of me trying to make myself better than anyone else because of the ideology I carried,” he says. “It was being part of something, creating something. When you’re locked in, you try to create some control in your life.”

Boccardi was released from CSP to the street in 1995, ill-prepared for life on the outside. He was bristling with resentment, quick to take offense at any perceived act of disrespect. He was also smoking crack and drinking. “I built this mentality in prison, this expectation of the way life should be,” he says. “It was all based on bullshit.”

On Mother’s Day, he got into an argument with a bartender at a dive in Colorado Springs and was ordered to leave. He demanded a refund for the five-dollar pitcher of beer he’d just bought and was refused. He returned to the bar with a golf club and a carpenter’s hatchet. He sunk the hatchet into the bar and ended up facing charges for menacing and “public order” crimes, enough to send him back to prison for another three years.

In those days, if you didn’t “earn your way” out of solitary by good behavior, you were placed back in solitary on your next offense. Boccardi went back to CSP and his fantasies. Over the next ten years, he kept making the journey from lockdown to the street to lockdown again. He would be hauled back for a parole violation or for fighting, and sometimes both – a fresh assault in custody after he was already facing parole revocation. Part of the problem was that he still hadn’t found a way to control his manic episodes; at times his behavior was a mystery even to himself. At the Ordway prison he got into a fight hours before he was supposed to be paroled. It was as if he had no interest in the outside world anymore.

“I found out why guys go back to prison. It’s called loneliness.”

Yet the world he’d fashioned inside proved to be more fragile than he expected. Some of the dudes he’d looked up to, his Aryan Syndicate brothers, ended up dying horrible deaths, strung out on heroin or succumbing to cirrhosis or other complications of hepatitis C. In their place were young hotheads trying to make a name for themselves and nursing their own violent fantasies. For close to three years of his time in CSP, Boccardi lived next to a troublemaker named Evan Ebel, who went straight from ad-seg to the street in 2013 and murdered two people – including DOC executive director Tom Clements, a reformer who was working to end the system’s reliance on solitary confinement.

“He was an angry fucking kid,” Boccardi remembers.

Yet Ebel scarcely stood out in the freak show that was CSP. Boccardi could sense the years of isolation taking his humanity away, making it difficult for him to feel anything. “People I knew were killing themselves with heroin because they couldn’t take it anymore,” he says. “I saw men break. I saw men eat their own shit in CSP. I couldn’t see myself dying in that place.”

Finally getting wise to himself, he started walking away from confrontations rather than escalating them. Out of ad-seg and awaiting parole, he saw something on the yard at Limon, an apparent gang recruitment effort, that filled him with disgust.

“The thing that got me the most was watching this 50-year-old man put his arm around a 22-year-old kid,” he recalls. “I mean, that kid’s getting ready to do parole; he shouldn’t be in Limon to begin with. But they create an environment like that, with people who have nothing to lose getting next to people who are getting out in three or four years. This guy is 22. Don’t bring him down.”

The scene reminded him of how quickly in his first prison stretch he’d been cast among the wolves at Limon. That kid was him.

He decided to change his life. When he got out in 2008, he worked with his psychiatrist and found a more effective medication for his bipolar condition. (“It allows my brain to slow down at night and helps me deal with stress a lot better,” he says.) He disavowed his gang ties and had his offensive tattoos inked over. He jettisoned old connections and what he calls the “skinhead Nazi thing.” He successfully navigated parole.

“The best thing that happened to me is I changed my friends,” he says. “I don’t want to be around that prison mentality anymore. What these guys don’t understand is, if you’re in prison, you’re not going to Valhalla. You’re not a hammer. You’re a slave to the government.”

Released from prison last year, Jeff Johnson filled out 34 job applications but got no offers.

Alan Prendergast

Drawing on many years of experience – 23 years in prison on robbery and assault charges, seven years back on the street as a law-abiding citizen – Kevin Chillis has had ample time to reflect on the re-entry problem.

“I found out why guys go back to prison,” he says. “It’s called loneliness. You might be with your whole family, but there’s a loneliness when you leave prison and come to society that only other people who’ve been in prison can feel. They exist in it. It’s more comfortable to go back to prison, because prison has become normal and the streets have become abnormal.”

When Boccardi got out a decade ago, in the middle of a recession, he struggled to make ends meet. The jobs he could find, usually washing dishes or doing prep work for restaurants, were often short-lived. The Internet had taken over the world in his absence, and bosses and co-workers seemed to treat him differently as soon as they Googled his name. The first thing that popped up was the 1994 Westword article about Gardner’s murder. He rarely had a chance to explain that he was not that dumb kid with the swazzie tattoo anymore before he was shown the door.

Many times he never even got as far as a Google search; if his admission on the employment application that he had a felony record didn’t torpedo his chances, the background check would.

The local economy has rebounded with a vengeance, but barriers to employment remain a problem for many ex-offenders. Jeff Johnson, released from the DOC last November after 24 years, says he filled out 34 job applications in his first two months on the street. He didn’t receive a single response. “People see you’ve got a conviction, and that’s all she wrote,” he says.

Johnson was originally sentenced to life without parole at the age of seventeen for a fatal stabbing in an Aurora parking garage. Like Boccardi, he spent several of his early years in the DOC in solitary confinement. But his co-defendant eventually admitted that Johnson was more of a shocked spectator than a participant in the crime, and a U.S. Supreme Court decision banning mandatory life sentences for juveniles forced Colorado to resentence and release him. In prison he was active in programs that help inmates prepare for release, and he wants to establish more of them on the outside.

A few weeks ago, Johnson was at the State Capitol, testifying in support of a “ban the box” bill that would remove the question about criminal convictions from initial employment applications; employers would still be free to ask about any criminal record at a later stage of the process. Colorado state agencies already prohibit questions about a criminal record until the applicant has become a finalist for the position, and two-thirds of the country’s state legislatures had already passed similar laws.

The Colorado Legislature approved the proposal earlier this month; it awaits Governor Jared Polis’s signature.

Carol Peeples, executive director of Remerg, says

Anthony Camera

Johnson recently found a position in a nonprofit’s career development program, which pays him a stipend while he sharpens the skills he has to offer an employer. He believes banning the box would have made a difference in his job search. “If I could have got some face time, I guarantee you I would have gotten a chance with one of them,” he says. “I could have shown them what I could do, prove myself to them.”

“‘Ban the box’ can help someone get their foot in the door,” says Carol Peeples, the executive director of Remerg, a Denver nonprofit that seeks to connect ex-offenders with community resources. “We’re reaching that tipping point where so many people have a criminal history that it just makes sense.”

Employment is, of course, just part of the challenge for offenders trying to acclimate themselves to life on the outside. There’s been an explosion in recent years of public and private efforts, many of them listed on the Remerg website, to assist parolees struggling to find housing, transportation, food and clothing, health care, “life skills” and other needs. The DOC has launched a re-entry mentoring program that matches volunteers with offenders about to be released. On a larger scale, since Clements’s murder the department has instituted dramatic changes to aid the re-entry process, including moving prisoners with mental illness into “residential treatment programs” rather than ad-seg – which no longer officially exists.

Many of the re-entry programs and services weren’t available when Boccardi got out a decade ago. It took him a while to figure out how to deal with the PTSD symptoms he was experiencing after close to ten years in solitary, including agoraphobia, anxiety and a tendency to lash out when startled. The medication helped. So did pacing his apartment, in much the same way he used to pace his cell.

“That’s the most definite change I’ve seen in Rick,” says Brian Palmer, who met Boccardi shortly after his release and became a close friend. “When he first got out, he was a lot more aggressive and kept to himself. He didn’t have a sense of boundaries and space. But he’s really learned to calm himself. He’s a much different person now, more level-headed.”

Boccardi acknowledges he still has moments of depression and anger, especially when he’s out of work. But he also has a service dog named Thirteen (after the amendment that abolished slavery) and his gallows humor, the essence of his standup performances.

“Rick’s sense of humor is reflective of the stuff he’s been through,” Palmer observes. “It’s not for everybody, but I think a lot of his stuff is hilarious.”

On stage at Loonees, Boccardi stumbles over the new material, a bit about prison guards and cavity searches. The punchline doesn’t bomb; it simply skulks away. Boccardi grimaces and quickly shifts gears.

“I’m a cancer survivor,” he announces. “Any cancer survivors in the audience?”

He gets a round of applause for his five years of remission, takes heart and plunges forward, to a growing chorus of laughter:

“I don’t know if you know what it’s like to be told you have testicular cancer. It’s like being kicked in the balls… You start thinking about positive things you can do with one testicle. Cross my legs on the bus and save room. I don’t have that extra weight down there, so it’s like my dick got a facelift… I’m six-feet-four with ‘Freedom’ tattooed across my neck, and you’ve got a 50-50 chance of kicking me in the balls… There’s nothing like losing your testicle, having your manhood challenged and going through chemo – “

Just as he’s gaining momentum, the stage lights start flashing, signaling that he’s out of time. Boccardi grins, thanks the crowd and steps down.

On the drive home he replays his performance in his mind, thinking about how to shape it and work it, what bits to eliminate. “You really don’t know what works until you try it out,” he says. “When you get them laughing, that’s the greatest feeling in the world. There’s nothing like it – that connection.”