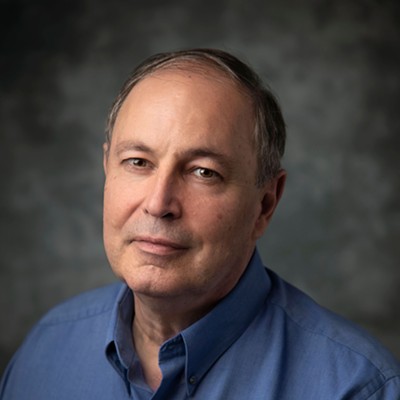

Sitting in his law office 36 floors above downtown Denver, Ken Salazar uncorks a speech he's aired frequently in the past few months. The Taylor Ranch, he says, is "a monument to the history of the Southwest and the coming together of two cultures." There is "an economic and cultural and historical impetus" for resolution of the conflict.

"I have no regrets about having gotten involved in this," he says. "I always prided myself on being a problem-solver, and we already have accomplished a lot."

Formerly the governor's chief legal advisor and one of the most prominent Hispanics in state politics, Salazar has followed events in San Luis closely for years. He was a vocal critic of the undercover poaching investigation--which, he says, he didn't learn about until the day of the raid.

Since then, Salazar has been involved in various state efforts to assist economic development in the valley, including failed discussions between Zach Taylor and state and federal officials over a proposed purchase of la sierra by the U.S. Forest Service in 1990 and 1991. He was the logical point man for any state initiative on the ranch and drafted the executive order last fall creating the Sangre de Cristo Land Grant Commission, naming himself as chairman.

On paper, the commission was an impressive fusion of federal, state and community interests. Its 22 members included three state legislators, Division of Wildlife and national and state park officials, as well as ten "locals," including the mayor of San Luis, a county commissioner, Father Pat and representatives of various economic-development and citizens' groups.

The blue-ribbon character of the panel seemed to ensure that its recommendations would carry substantial weight. Yet the commission's report was hardly off the presses before some members were seeking to distance themselves from it. Even if the commission's work hadn't stalled when Taylor balked at the state's offer, there were plenty of other stumbling blocks ahead.

The first problem had to do with the composition of the group itself. Salazar defends the commission as "broadly representative" of valley interests. But he says he was unaware, until a reporter pointed it out to him, that he had appointed three sets of brothers-in-law to the panel.

Costilla County politics can be a byzantine arrangement of blood and marital ties among a few powerful families: The county administrator (who serves on the state commission) is married to a county commissioner's niece and is the brother-in-law of the head of the Vega Board (another member of the commission), whose cousin happens to be a member of the Colorado Wildlife Commission (ditto), who is the brother-in-law of the head of the Costilla County Citizens for Better Government (ditto)--and that's only a partial accounting.

While most of the locals on the commission are herederos, few are actively involved in the lawsuit, and critics felt the panel should have included more people who depend on farming and ranching for their livelihood. "Main Street developers and politicians were making decisions for people up in the hills," says Glenda Maes, a Land Rights Council boardmember who monitored the commission's meetings.

Other concerns emerged as the locals struggled to reach an accord with park and wildlife officials on what Salazar calls the "structure of governance" for the ranch. The commission report, hammered out in just ninety days, is understandably vague as to how many acres would be set aside for a state park, or how much timber, pasture and elk would be reserved for local use. But such details are at the heart of whether the land could be jointly managed.

Bruce McCloskey, deputy director of the Colorado Division of Wildlife, says the commission achieved a "comfort level" on key issues of wildlife management. But Jim Durr, a Fort Collins attorney who is writing a book about the poaching raid, believes that any partnership between the state and local subsistence hunters--many of whom don't see poaching as a big deal, as long as the meat goes to feed the family--would be a rough ride.

"The report says, we're going to respect your values, but it's the Division of Wildlife who will really be the manager of the resource," Durr says. "Just see who has the power a few years from now, who's deciding the level of use."

Others say that locals' notions of recreation on the mountain and the state park model aren't compatible, either. "There would always be friction," says Mondragon-Valdez. "The park service has certain hours, they don't allow beer, you can't party all night. We used to go up there with our entire family, have a big bonfire, stay as late as we want--you think we're going to go into a state park and do that?"

Mondragon-Valdez, who runs an alternative energy consulting firm with her husband, Arnold, would like to see the mountain reserved for low-impact local use. She speaks with horror of the kind of "gentrification" and "amenity tourism" a state park might attract, from trailer hookups to burger palaces, mountain bike shops and real estate speculators.

It's a common theme in San Luis: State ownership would mean yuppie tourists eager to gawk at the quaint locals. "I graduated in 1956 from junior high school in Taos, and Taos then was just like here," says Gene Martinez. "Now if you go to Taos, all the Indians are in a little pueblo, a little zoo. They've been introduced to alcoholism, to drugs, to AIDS, and they're losing their traditional ways.

"The exchange isn't a fair one. I'm not keen on seeing a big bus over here with a bunch of tourists looking at me like I'm a monkey or something."

Significantly, local antigrowth factions weren't the only ones objecting to state involvement. Shortly after the report was released, newspapers across Colorado were peppered with letters of protest from sportsman's groups, asking why their tax dollars and hunting fees should help finance the purchase of the ranch when locals were going to enjoy "special rights" of access denied to the rest of the state.

Salazar's response is simple: Under the state's proposal, the people of southern Costilla County would kick in a certain amount of money--at one point the figure $4,000,000 surfaced--to purchase their "historic use rights," in the form of an easement. Funds would be raised through the nonprofit La Sierra Foundation.

"They weren't going to be given anything," Salazar insists. "The `special rights' deal was a red herring. A lot of people simply didn't want this project to go forward."

But the notion of an easement didn't sit well with the Land Rights Council contingent, which was still fighting in court for the historic use rights. "Why should we buy back something that is ours?" demands Gloria Maestas.

Mondragon-Valdez agrees. "Why should we buy anything now," she asks, "when we may be able to win in court and put ourselves in a better bargaining position?"

Mondragon-Valdez's view wasn't shared by most of the locals on the commission, who had already rallied around the concept of La Sierra Foundation. Even if the Land Rights Council wins its lawsuit, they point out, they still won't have title to the land--so it makes sense to pursue the easement and perhaps eventually purchase the ranch from the state, bringing it under exclusive local control.

"The Land Rights Council says, `The rights are already ours.' Be that as it may, still, the courts have ruled otherwise," says Maclovio Martinez. "I don't think the result [of the current lawsuit] is going to be any different than it was in the 1960s."

Martinez, who heads the Costilla County Conservancy District in addition to being county assessor, presented an ambitious proposal for the foundation at the first state commission meeting and pressed for La Sierra to have a leading role in acquiring and managing the ranch. He was politely rebuffed for being "premature" in his scheme.

"They said that we were going much too fast, that we were going harebrained, on our own," he says, shaking his head. "My reply to that was, `Yeah--you're standing still, so I'm going too fast.'"

Martinez said he "bowed down" to the commission process. But when the state's negotiations with Taylor foundered, La Sierra sprang into action. The group, which lists as its board of directors six of the ten local members of the commission--the same "Main Street" interests the Land Rights Council finds so nettlesome--has produced lengthy position papers denouncing the state's plan as "unrealistic." They've also distributed 40,000 copies of a fundraising newspaper, soliciting donations to help buy the Taylor Ranch, with plans for mailing 500,000 more pleas to conservationists across the country.

Martinez says the group is receiving donations at the rate of several thousand dollars a week and so far has raised more than $25,000. Since the group is not yet incorporated and is awaiting tax-exempt status, the money is being channeled through the Conservancy District, which also provided start-up funds. The two organizations are deeply intertwined, Martinez acknowledges, since the primary mission of both is to "protect the watershed" in the county from large-scale development such as logging and mining.

At the same time, La Sierra's position papers state that commercialization of the ranch--including a hunting operation on the scale of Taylor's current game ranching (which reportedly generates income of around $300,000 a year), grazing, hiking and fishing, possibly even some logging--"may be unavoidable" to generate short-term revenue to finance the purchase. The foundation's proposed by-laws also suggest that anyone who resides in southern Costilla County could qualify as a "land grant member."

Such language alarms the Land Rights Council, which initially supported La Sierra but has since demanded that the group stop brandishing the LRC name in its fundraising appeals.

"This land has a limited capacity," says Mondragon-Valdez. "If we open it to everybody and their dog who owns land here--and a lot of them now have a speculator's mentality--it'll be a catastrophe."

Although she was initially enlisted as part of La Sierra's local "working group," Mondragon-Valdez has emerged as the foundation's most vehement opponent. This spring she squashed a $50,000 grant application La Sierra made to the Catholic Church's Campaign for Human Development, protesting that her name was used without her knowledge after she'd resigned from La Sierra's board; ironically, she was the only boardmember listed who met the CHD's eligibility criteria, which requires that a majority of the project's directors have incomes below the poverty level.

She has also wrangled with La Sierra consultant Devon Pena, a Colorado College sociology professor who recently received a $140,000 government grant to study the development of Hispanic farms in the area. At conferences and in letters to grant underwriters, Mondragon-Valdez has denounced Pena as an "interloper" and an "academic speculator" who has misrepresented the degree of support for his research and for La Sierra. In an article published last fall, Pena claimed that La Sierra "has raised close to $6 million from national private foundations toward the purchase of the Taylor Ranch."

Pena denies any misrepresentation, insisting that the Ford Foundation and other groups have "pledged to help us," although no money has changed hands yet. (LRC sources say Ford Foundation executives have met with them, too, and have vowed to steer clear of the conflict between the two groups.) He ascribes his differences with Mondragon-Valdez to a misplaced sense of professional rivalry--Mondragon-Valdez is working on a doctorate on land-grant issues--rather than any possible competition between La Sierra and the LRC for funding and political support.

"Maria is opposed to any outsider coming and stealing the glory from her," he says. "She's a very angry young woman who's burning her own bridges."

Pena describes himself and other La Sierra backers as "pragmatists" willing to trade some degree of commercial use for acquisition and protection of the watershed. He talks about launching a "Sustainable Development Institute" and other low-impact forms of development on the ranch.

"I'm not going to romanticize people," he says. "Not everyone in that community has a strong land ethic, and there are people who would overgraze and destroy the land. We need to generate operating revenue to hire a couple of rangers."

While LRC members characterize themselves as the voice of the area's small farmers and ranchers, battling La Sierra's "oligarchy" of powerful politicians and developers, Pena stresses the common interests of the two. "Everyone agrees on protecting the mountain," he says. "Everyone agrees that the heirs should have, if not exclusive, then special use rights...The biggest point of difference is, do you only allow access to people who are heirs, or everybody? And who is an heir?"

Mondragon-Valdez concedes that the LRC hasn't yet fully defined who should have access to the mountain. Some believe the rights properly belong only to herederos who lost access in 1960 and their descendants; others say it should include heirs who have moved away from the valley because of economic hardship or all descendants of settlers who arrived earlier than, say, 1870. Gene Martinez figures there may be as many as 5,000 heirs--more than the current population of Costilla County--though many probably would not make use of their rights.

The debate may be moot, pending resolution of the lawsuit, but the squabble over who has the rights to la sierra has left some of the commission's original backers groaning with frustration.

"When you see how unrealistic some of the locals are, you ask why you're doing all this," sighs one participant. "When the deal didn't happen, they all went back to the rattle, just yelling at each other and saying the state was going to screw us."

But commission bigwigs aren't the only ones feeling frustrated. Salazar's proposal that the locals settle their differences with a referendum drew a sharp letter from Zachary Taylor, who finds it strange that the state and locals could have such an involved argument over land none of them owns at the moment.

"I suggest that any proposed solution directly involve the owners of the property," Taylor wrote, adding that Salazar's persistent references to "historic use rights" may constitute a slander of title. "It is our position (and the position of the federal court) that there are no historic use rights on Taylor Ranch."

Salazar's referendum proposal also served to further alienate his critics in the valley. For one thing, it appeared on the letterhead of Parcel, Mauro, Hultin & Spaanstra, the Denver law firm he joined after leaving the Department of Natural Resources; the firm represents Battle Mountain Gold, operators of a cyanide-leach gold mine outside San Luis that county officials and activists have been fighting for years.

Salazar denies that any conflict of interest exists, since he doesn't work on issues involving Battle Mountain or with any other clients he may have encountered as a state regulator. But his referendum proposal, backed by the La Sierra faction, fell flat with the Land Rights Council.

"I don't think he has any business coming here and suggesting what should go on in our county elections," says Glenda Maes. Even if La Sierra won a vote of confidence, she adds, it could hardly be binding on the lawsuit plaintiffs.

Maria Mondragon-Valdez notes that five current and former county officials have been indicted on charges of election fraud. "How can we trust a vote when a grand jury is looking at voter fraud in this county?" she asks.

"The commission, just like the La Sierra Foundation, it's just a small group of people," she says. "And they're hiding behind this myth, the myth of consensus, that `this is what the community wants.' We're saying, hey, our goal is to litigate. We don't have time to run around doing what Ken Salazar wants. Who is Ken Salazar?"

Ron Sandoval describes himself as an "economic refugee" of Costilla County. One of eleven brothers and three sisters, he grew up on a thirty-acre ranch a few miles outside San Luis and became active in the Land Rights Council in the late 1970s but eventually had to leave the county to find work elsewhere.

Sandoval, who now works in legal services in Phoenix, has researched land-grant issues in Spain and Mexico. He doesn't believe the controversy over la sierra will be resolved through state ownership or a foundation buyout. The real issue is that the "spiritual relationship" the herederos have had with the land is being lost, he says, and people will need "training" before they're ready to use the mountain again.

"The fact is, some local people have had access to that land and they've abused it," he says. "I don't think it can sustain people by itself, but it's there to help people survive, not for them to exploit it or destroy it."

One of Sandoval's brothers was caught in the poaching raid five years ago. His father, a former county sheriff, defends poaching as a "way of life" in the valley, but Ron is troubled by the fact that so many people could be enticed to shoot elk and even eagles for a few dollars offered by a federal undercover agent.

"If they had that spiritual understanding, they wouldn't have been killing those animals for money," he says. He contends that the true culture of the county is mestizo, drawing on Native American as well as Hispanic traditions of land use--"and we need to learn how to respect the land all over again."

Ever upbeat, Ken Salazar believes the locals may get their chance. "Taylor needs to decide whether or not he wants to deal with the state or the local community, and at what price," he says. "I have some ideas, some options that might work that I'm going to try to talk to him about."

Tom Macy, western director of the Conservation Fund, the nonprofit agency that's been spearheading negotiations with Taylor on behalf of the state, says the door to a deal is still open. "It slipped away for now, but it will come back," he says, "because Mr. Taylor has a marketability problem."

Preserving 77,000 acres of semiwilderness--marred by some previous efforts at development but virtually untouched at higher elevations--would be a coup for Salazar and the Conservation Fund. Still, the "real story," Macy insists, is the quest to reunite the locals with the mountain.

"When you see that big mountain looming over that little town and how the mountain supports the town--they need to be put back together," he says.

But the view keeps changing, depending on who's leading the tour. Locals tell the story of how, just last year, the valley was visited by a timber czar from Oregon who was pondering a purchase of the Taylor Ranch. He came upon one of Taylor's neighbors and complimented him on his modest but splendid-looking piece of property.

"Yeah," the neighbor said, "it's a little piece of hell."

Then he looked up at the mountain and grinned.

"And whoever buys that ranch," he said, "is going to have a big piece of hell."

end of part 2