“My dad used to always walk by and say, ‘That’s the house I want,’” remembers Salvador Torres’s son,

David. “It was a beautiful house, the nicest on the block. He fell in love with it.”

The Torreses purchased their dream home for $47,000 in 1987. They decided to keep the first house as a rental; Salvador operated a vehicle repair business out of the back yard and didn’t want to relocate it to the new house. But when CDOT offered them a little over $20,000 for their first house, they agreed to the deal, happy to use the money to pay off the mortgage on the second house and own it outright. "It was a relatively smooth process,” says David, who helped his parents move forward with the agreement.

After the acquisition process was finalized, Salvador Torres applied for a permit to move his business up the block — but the permit was denied. The news was devastating; Salvador couldn’t understand why the government would take his home and then deny him the possibility of restarting his business. He had trouble recovering from the loss, and while Rose continued to work, Salvador was never able to find another secure job.

“We weren’t hurting, but we weren’t living lavishly,” says David, who lived with his parents until he moved out of the family home and to Thornton in 2010.

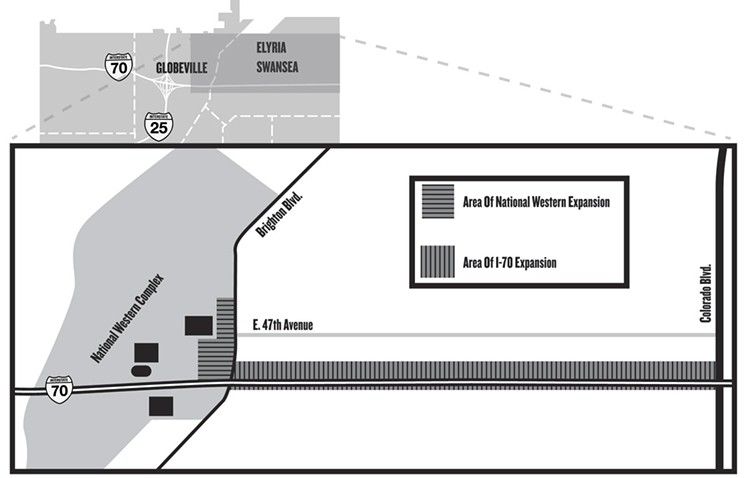

Then in 2013, the neighborhood started to buzz about more change in the area. Mayor Michael Hancock had created something called the North Denver Cornerstone Collaborative, a collection of six massive projects in neighborhoods throughout north Denver, including River North, Globeville, Swansea and Elyria, where the Torreses lived. Just blocks away, the city was planning to redevelop Brighton Boulevard, while a little farther east, nearly $1.2 billion would be pumped into Central 70, a project that would drop the old I-70 viaduct below grade and cap it with a four-acre park. And one part of the NDCC portfolio hit even closer to home: the plan to expand the National Western Complex into a 270-acre, public-private National Western Center, stretching from the South Platte River to Brighton Boulevard and more than doubling the facility’s size.

“They knew about the National Western Center; they lived right across the street from it,” says David. His parents also guessed what that enormous expansion might mean for their dream home. Then in October 2014, Salvador Torres died in his sleep of cardiovascular complications. “It was abrupt,” says David. “We always say my dad either knew and didn’t want to deal with it, or that it would’ve killed him anyway.”"My dad used to always walk by and say, 'That's the house I want.' It was a beautiful house."

tweet this

After his father’s death, David, who’d recently been laid off from his job as a ramp supervisor with SkyWest Airlines, decided to move back in with his mother. Two weeks after he returned to the house on Baldwin Court, Kelly Leid, then the executive director of the NDCC (and now the director of the National Western Center), and assistant Erika Reyes Martinez knocked on the Torreses’ door.

Denver has grown at a record-breaking pace over the past few years. Demand for housing has skyrocketed, and so have property values: The median percentage change for the City and County of Denver between 2015 and 2017 was 25.9 percent. The average citywide rent has also risen, from around $1,000 a month in 2011 to over $1,500 in June 2017.

Some of the biggest increases have come in surprising places, including historically poor neighborhoods like Valverde, Montbello, Westwood, West and East Colfax and Ruby Hill. But the most staggering changes are in Globeville and Elyria-Swansea. These mostly immigrant neighborhoods developed around the factories, smelters, stockyards and meatpacking plants that sprang up along the rail lines at the turn of the last century. In the 1960s, construction of the I-70 viaduct split the largely industrial neighborhoods in half. Then, adding insult to injury, Globeville and Elyria-Swansea languished as factories closed or relocated and employment dropped. White working-class residents moved out, and Globeville and what’s generally classified as Elyria-Swansea quickly became predominantly Latino. Today there are just over 10,000 residents between the two neighborhoods; 61.33 percent of Globeville’s residents and 82.89 percent in Elyria-Swansea are Latino, according to 2015 data from the Piton Foundation. Statistics from the City and County of Denver show that in Elyria-Swansea, 34 percent of the residents are foreign-born, as are 21.6 percent in Globeville.

While historically the housing stock in this area has been some of the cheapest in the city, that’s changed as a result of Denver’s upcoming development projects and market pressures from buyers pining for entry-level homes. Data from the Denver Assessor’s Office shows that Elyria-Swansea had the second-highest median property-value change — 54 percent — of any neighborhood in the entire city between 2015 and 2017. Globeville was not far behind, at 40.8 percent, and values are predicted to grow at least another 8 percent in the next year. In 2017, the neighborhoods saw 48 homes sell for $170,000 or more; in 2010, only one home sold in that range. And as property values increase, owners who lease homes transfer the burden of rising taxes onto renters. In Globeville, rent increased from an average of $923 per month in November 2010 to $1,604 in May 2017.

For years, Mayor Hancock has hailed Globeville and Elyria-Swansea as integral sections of the “Corridor of Opportunity,” which stretches from Union Station to Denver International Airport. “We are embarking on the greatest cascade of investments we’ll see in our lifetimes,” the mayor said at his State of the City speech last month. Budgets for the six NDCC projects total between $5 and $6 billion; the city’s 2017 General Obligation Bond proposal has also allocated just under $50 million for transportation and mobility projects in the neighborhoods.

Hancock and his supporters laud these initiatives as bringing much-needed infrastructure to historically neglected communities. A walkable Brighton Boulevard and other road repairs, expanded transportation services and stations linking the area to downtown Denver, better living options, and a National Western Center that the mayor claims will be “a dynamic year-round tourist destination and agribusiness incubator” have all been touted as remedies to decades of poverty, unemployment and a stunted economy.

As public investment has surged, so has private. At least fifty parcels of land have recently been purchased in Globeville, Elyria-Swansea and nearby RiNo for seven-figure prices. Even the industrial makeup is changing, as rezoning turns parcels into commercial or mixed-use properties. Some are now zoned for buildings as high as twenty stories, in a low-density neighborhood of primarily single-family, single-story homes."We are embarking on the greatest cascade of investments we'll see in our lifetimes."

tweet this

While their neighborhoods appear more desirable than ever, many community members feel alienated and uncertain about their futures. CDOT’s Central 70 project has met with fierce opposition, as activists band together to protest what critics call a “boondoggle” that poses health and environmental risks. The expansion is paired with a massive stormwater drainage reroute intended to protect the below-grade interstate from flooding, but which requires digging through a Superfund site in what’s been deemed “the nation’s most contaminated zip code.” Though the plan to lower the viaduct below-grade is meant to reunite the divided communities, many residents worry that the five-year disruption of construction will divide them even further.

If they can still live there at all, that is. Some of the organizations studying plans for the area are concerned that development in Globeville and Elyria-Swansea has greatly increased the risk of the displacement of an immigrant community that, despite a lack of resources, has grown deep roots. Although more than half of the residents in both neighborhoods are living below the poverty line, with low educational attainment rates and high rates of unemployment, about 50 percent are homeowners, and 70 percent of those have lived in the neighborhoods for ten years or longer. Although a civil-rights investigation was conducted after activists claimed that the Central 70 project disproportionately affected these marginalized communities of color, the response from the Federal Highway Administration claimed that the project had a “substantial legitimate interest” in easing traffic congestion, even if the largely Latino populations faced potential displacement.

While some residents worry about hanging on to their homes, others worry that the buildings will disappear altogether. The Central 70 and National Western Center projects collectively require the acquisition and demolition of 81 housing units and 49 commercial properties. So far the National Western Center has acquired about 76 percent of its parcels, while CDOT has already begun demolishing homes. But even if displaced residents are compensated adequately for their homes, they may find it impossible to locate a replacement anywhere near the neighborhood.

David Torres by his parents’ dream home, in the path of the National Western Center expansion.

Marvin Anani

“It was a euphemism,” says David. “They didn’t say that they were going to take the house.” But he and his mother knew exactly what this visit meant: After nearly twenty years, they were about to lose another home to the government.

“We wanted to make sure people had a chance to see the master plan and ask questions, and we wanted them to be able to do that face to face,” Martinez, who heads communications for the Mayor’s Office of the National Western Center, says of visits like the one made to the Torreses. “In good faith,” she adds, the National Western Center team decided to adopt the guidelines of the Uniform Act, a federal law that stipulates certain procedures be followed during right-of-way acquisition processes, despite the fact that Denver is using no federal funds on this venture. Among other things, the act stipulates that owners be able to hire their own appraisers and have their fees paid by the government; the city also agreed to pay the cost of relocation for homeowners and, for renters, to pay any difference in rent for a year.

While Martinez acknowledges that the city has faced challenges, she says that invoking eminent domain — the constitutional power of the government to take private property for public use — is always a last resort. Only when homeowners are either completely unresponsive or don’t like their settlement package does the city file an eminent-domain claim in court, she explains. Of the eight cases where the city has found this necessary so far, she notes, all have involved the acquisition of commercial businesses. “We’ve taken this seriously and tried to be transparent,” Martinez says, adding that the city does everything it can to meet residents in the middle.

But the Torreses say they didn’t feel the city was accommodating or transparent. After Leid and Martinez’s visit, they didn’t hear anything about a potential acquisition until a few months later, when they received a letter officially informing them that the city wanted to buy their property. The master plan had been approved in March 2015, and their home had been bumped up to phase one. But even after that news, the Torreses were left in limbo for another year. Every once in a while, the city would call to say that someone would be stopping by to look into various aspects of the house. One person checked for outstanding environmental hazards; a few were appraisers. Reports stemming from these visits were supposed to be shared with the Torreses, but they say that never happened. David called the city periodically, but rarely got any information. “We knew it would happen, just not when,” he says. Finally in August 2016, the city sent them an offer.

“There were typos in the documents,” David recalls. But there were other things that concerned them more. The relocation housing benefit they were offered was $255,000 — but if they wanted to receive an extra $84,999, the Torreses would need to purchase a home worth no less than $470,000. “Basically, in order to get a total of $340,000, we would have needed to go $130,000 in debt,” says David, who hired a lawyer.

The lawyer came in handy, because David found communicating with H.C. Peck Associates, Inc., the national right-of-way acquisition and relocation firm that was handling the process for the city, increasingly difficult. “They would give roundabout or indirect answers to any question we had,” he remembers. They were also very hard to reach, despite the fact that whenever he missed a call from the firm, he says, he was quickly reprimanded for being uncommunicative and unwilling to reach a deal.

The city began offering the Torreses different relocation options, but David and his mother felt they weren’t comparable to their home. The house on Baldwin Court was 2,000 square feet above grade; the city kept proposing houses around 800 square feet above grade, with more space in the basement. “Cost-wise, above-grade square feet are ten times more expensive than below-grade,” explains David, so by finding houses with large basements and small first floors, the city would be able to save money.

On top of that, the city wasn’t providing any options in Denver proper; most of the houses were in Lakewood or Adams County. Rose Torres had been living on the same block in Elyria for forty years; David had two brothers and a sister living in Swansea, as well as many other close friends there that he considered family. The Baldwin Court house was a half-mile from the Nestlé Purina factory, where he’d found a job, and every day his mother drove her grandkids to school at University Prep, just over a mile away. Moving as far away as Adams County or Lakewood would disrupt their lives.

But in the Denver market, and especially in neighborhoods close to Elyria-Swansea, there were hardly any comparable homes listed, and those that were had much higher price tags than what the city was offering. “Between January and April of 2017, my realtor had never seen the inventory so low,” David recalls. If he and his mother wanted to live anywhere close to their old home, they’d need a better compensation package."They made it more stressful and painful than I ever could have imagined."

tweet this

Steve Kinney, the local realtor providing David with aid and advice, finally persuaded the city to compensate the Torreses $440,000 for their home. “That’s a lot of money,” David admits. But prices were rising all over town, and David still couldn’t find a comparable house nearby. Finally, one became available just to the south in the Whittier neighborhood, on 31st Avenue and Gaylord Street. It was listed at $579,000. David submitted it to the city, but the option was quickly rejected. He expected the house to vanish from the market just as soon as it had appeared, but was surprised to see the listing linger for a few months, giving him a little more time to fight.

Finally, the city agreed to compensate the Torreses $499,000, which they could use to buy the house on Gaylord. After living mortgage-free for twenty years, Rose and David Torres had to take out a loan to bridge the gap in their compensation package and the new home’s price. They finally moved into the house this June, three years after they’d first heard the city might be taking their house.

“I don’t wish this process on anyone,” says David. “I’m glad my dad didn’t have to deal with it — it would’ve killed him. They made it more stressful and painful than I ever could have imagined.”

The Central 70 project that will replace viaducts is just one of the changes in this part of north Denver.

Westword

“The People’s Survey: A Story of Displacement” had collected startling statistics from some 500 people living in Globeville and Elyria-Swansea, in the shadow of projects like Central 70 and the National Western Center. As the report’s opening statement notes, “While Denver’s economy thrives, our families and our neighbors carry much of the burden of Denver’s upcoming economic redevelopment. We urge you to consider the disproportionate hardship that our families are facing, and we compel you to bear witness to the damages that Denver’s housing crisis are inflicting on the families of Globeville, Elyria-Swansea.... While Denver’s housing crisis is most exaggerated in GES, the crisis comes as an afterthought of billions of dollars of public and private investment.”

Even before the GES Coalition conducted its survey, considerable data existed regarding the vulnerability of Globeville and Elyria-Swansea residents. Information from the Piton Foundation shows that over a quarter of families in both neighborhoods live in poverty, and around three-quarters make less than the median Denver income of $60,000 a year. But the GES Coalition survey went further, going beyond just numbers to find out how residents felt about potentially being displaced. Not only are many of them poor, but a large portion of homeowners in the area are older and either unemployed or retired, and around a third of those between ages 54 and 60 spend more than half of their income on housing. For these residents, finding comparable housing in the Denver market would be almost impossible. Of the residents who rent, just over half have no lease at all, which puts them at greater risk of being evicted on short notice. Many of the rental units were also occupied by families: The survey found that half the units were home to three or more adults, and 56 percent had two or more children living there.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the survey also found that 80 percent of the residents in the area want to stay in their homes. But the respondents who were homeowners listed a wide range of factors that made their living situation uncertain: The most common was market pressures to sell, followed by I-70 construction. Of the 20 percent who voiced an interest in moving, very few said they had hopes of turning a profit. About two-thirds had already received offers — one resident at the gathering recounting receiving calls, fliers and knocks on the door daily asking him to sell — and about a quarter simply wanted to move for fear of being displaced by further development.

The goal of the survey, according to the GES Coalition, was not just to get real information, but also to provide a voice to the countless residents who are feeling increasingly insignificant in the face of all the major undertakings around them.

Until her son was diagnosed with lupus, Raymunda Carreón was a homeowner. She and her husband had moved their family to Swansea in 1999, and in 2000 took out a sub-prime loan to help pay for a home. But in 2005, their son’s diagnosis made it impossible for him to work, and without his financial contribution, the family’s loan ballooned out of affordability. They were also buried in medical bills: Lupus causes the body’s immune system to attack its own tissues, and in the case of Carreón’s son, the inflammation affected his kidneys. He needed dialysis treatment once a week and was on eight different medications that Carreón and her husband had to pay for out of pocket.

The family lost their home to foreclosure and moved into a tiny duplex in the neighborhood. Their son, who’d been living with his girlfriend, moved back in with his parents after learning that he didn’t qualify for a kidney transplant. “He told me, ‘If this is the case and this is how it is going to continue, I don’t understand what I am looking forward to. I feel like I just shouldn’t live anymore,’” Carreón remembers.

The duplex was cramped — Carreón was living there with her husband, children and grandchildren — and in disrepair, but the $600-a-month rent was affordable, and Carreón had a positive relationship with her landlord. Once, she says, a tile fell from the ceiling and nearly hit her in the head; when the landlord was told, she came and fixed the roof immediately.

But last year her landlord moved to Nebraska, and around the same time, the Carreóns’ yearly lease expired. The duplex was purchased by a mysterious LLC and placed in the hands of a property management company. Carreón applied for a yearly lease with the company, but was denied and instead given a month-to-month agreement. Then one day a man came to Carreón’s door; he told her that the rent was increasing from $600 to $1,000 a month but assured her that the jacked-up price would cover repairs to the house. Carreón assumed he was the owner and agreed to the rent increase; none of it was put down in writing. Weeks passed, but Carreón and her family didn’t see any repairs. Finally, she and Robin Reichhardt, a community organizer for the GES Coalition, went to talk to the property management firm.

“They said they weren’t going to fix it,” Carreón recalls. In fact, they learned that the man she had talked with was not the owner, but an agent at the property management company who denied ever acting as the owner. Disheartened, Carreón left with the secretary’s contact information, hoping that improved communication would stave off additional problems. After a while, the secretary told her that the other side of the duplex was going to be remodeled; when this was completed, Carreón and her family would be allowed to temporarily move into the renovated side, so that their side could be fixed up as well. Again, the plan was confirmed only by word of mouth. And again, when the renovations were finished and Carreón asked if she could move in, she was given a different answer. This time, she was told she could move in only if she paid the new renter’s fee of $1,600 a month.

Carreón’s living situation is still unresolved. In July, her rent was increased another $150. On a month-to-month lease, she faces the prospect of being evicted at any time, with only a seven-day grace period. She and her family have tried applying for a loan to buy a home, but they only qualify for $200,000, which isn’t enough to buy a place in the community. “It is impossible to find anywhere to go,” she says. “If we can’t stay month-to-month, we have nowhere to go.”

Carreón’s own health has started to deteriorate. “My doctor says the solution is to stop stressing, but it’s difficult because we’re unsure of our future,” she explains. So far, the best outlet she’s found is working with the GES Coalition. “I’m hopeful for solutions,” she says, “but I’m not putting it all in their hands.”

Her last hope is that someone “with higher powers” — not God, but a politician — will stand up for what is right and come forward with a solution for the people of Swansea.

Carreón’s situation is not unique. Today, 17 percent of the homes in Globeville and Elyria-Swansea are owned by clandestine companies, which usually register with the Colorado Secretary of State’s Office just days before making a purchase. Colorado disclosure laws don’t require LLCs to list all of their active members, so the name of one registered agent is often the only information in a public file. In Carreon’s neighborhood, speculation abounds as to who is really behind these companies, and many believe the LLCs are shells for larger industries or developers.

Candi Cdebaca, a neighborhood activist and member of the GES Coalition, says the “onslaught of development” and sudden attention on a community that’s long been ignored aren’t evidence of a desire to rectify years of neglect, but ways to capitalize on economic growth. “If they wanted to help our communities, they should have started long ago, when people needed basic things like sidewalks, curbs, bus stations, bridges,” she says.

Albus Brooks, Denver City Council president and the representative for District 9, which includes Globeville and Elyria-Swansea, recognizes that the massive changes in the neighborhoods will affect the residents. “Any time you improve a community, it increases the value of that community,” he notes. But Brooks also points to several city initiatives created to counter displacement and help residents reap the benefits of development in their communities.

In May 2016, the Denver Office of Economic Development released a report analyzing ways to mitigate displacement caused by gentrification, and Mayor Hancock subsequently set aside $8 million of the city budget for affordable housing; he also announced plans to dedicate $15 million to the same cause over the next ten years. Earlier this year, Hancock reinstated an affordable-housing fee for developers to encourage the inclusion of affordable units in new developments. Then, in collaboration with the city, the Urban Land Conservancy purchased a six-acre parcel of land at 48th Avenue and Race Street in Elyria-Swansea, with plans for a 560-condo complex that will sell over half of its units at rates affordable to those making less than 80 percent of Denver’s median income. Never before had the city done anything “so forthright” to counter displacement with affordable housing, Brooks says. And in the fall, he adds, he hopes to propose an ordinance that would create greater tenants’ rights in the city.

CDOT has also made an effort to address the ramifications of the Central 70 project, allocating $2 million of the project’s overall budget for affordable-housing solutions in Globeville and Elyria-Swansea. On top of that, it’s dedicating nearly $20 million to improvements in air quality and noise control at Swansea Elementary School (which is kitty-corner to the interstate expansion) and 300 nearby homes. “We’ve taken steps never done in Colorado, nor by most DOTs in the nation,” says Rebecca White, a CDOT spokeswoman. Last month, CDOT held a ribbon-cutting ceremony for a career-training and resource center linked with the Central 70 expansion project. Built through several public-private partnerships, the initiative is intended to provide participants with job training and hard skills; it specifically requires hiring 20 percent of the Central 70 expansion team from communities most affected by the project.

But for Cdebaca and other members of the GES Coalition, these initiatives are too little, too late. Even Brooks, who says the city has been acting “aggressively” to counter displacement, admits that “policy is for the next generation. It rarely affects individuals today.”

Given that, Cdebaca wonders why protective measures weren’t taken far earlier in a planning process that has been in the works for over a decade. If it was a priority, “affordable housing should have been put into place prior to displacing residents,” she says. And while a six-acre development of affordable homes is exceptional, it also won’t be completed for years. “The National Western and I-70 projects should have been coupled with policies to protect current residents from the start,” she adds; in fact, Cdebaca believes that most of the city’s and CDOT’s recent measures only came about because of pressure from neighborhood activists.

Cdebaca points to a 2015 study commissioned by the OED and conducted by Community Strategies Institute that found that in order to successfully counteract the effects of demolishing 56 homes as part of the Central 70 expansion, CDOT should invest $14.5 million back into Elyria-Swansea; instead, CDOT invested $2 million. That amount was adequate to “trigger affordable housing units and leverage additional funds,” according to CDOT’s White, but Cdebaca and others wonder why the $14.5 million recommendation was ignored.

The GES Coalition is pinning some hope on the possibility of creating a community land trust in Globeville and Elyria-Swansea, partnering with Colorado Community Land Trust and Grounded Solutions, a national organization that provides local support for housing solutions. At the July press conference, members of the coalition announced plans to pursue a land trust, saying that if public capital isn’t invested now, residents may have no way to avoid being displaced. A land trust would involve negotiating with some sort of governing body to purchase land in the neighborhood and then lease it to residents at an affordable, stable price. The city has met with GES members to consider pooling resources, Brooks says, and while Denver officials are open to the concept, it’s tricky. “There are governing issues,” he explains, as well as challenges over “how the money is raised and guaranteed, and who holds it.” And then there’s the challenge of assembling the land itself, with available property now in such short supply in the area."The people trying to cash out don't care about the future of the community or who is left behind."

tweet this

All around north Denver, it’s impossible to miss the signs of change. In RiNo, at the start of the NDCC, the once-warehouse-filled industrial neighborhood has become an area of microbreweries, business incubators and multi-story apartment buildings. Cole and Whittier have seen extreme property-value surges, and parts of Five Points are unrecognizable. The eye candy of development — trendy stores, repaired roads and refurbished buildings, all signs of booming economics and opportunity — mask the fact that large populations of low-income people have seemingly vanished, pushed into other neighborhoods.

“The people trying to cash out don’t care about the future of the community or who is left behind when they leave,” says Cdebaca.

“I always say this is ‘Denver’s last frontier,’” says Drew Dutcher, president of the Elyria-Swansea Neighborhood Association and a member of the GES Coalition. Once it’s gone, he wonders, “Where else is left?”

In today’s real estate market, the fact that the Torres family was able to find a house relatively close to where they’d lived for generations seems nothing short of miraculous. But David Torres’s years-long battle had nothing to do with miracles: He was armed with willpower and resources, and those are in short supply in Globeville and Elyria-Swansea these days. “I think people are afraid to fight,” he says.

But David had strong motivation: his mother. “I was just trying to get my mom an easier transition,” he explains. “She was on that block for over forty years.” He didn’t suffer the way she did when she realized her dream home would be demolished; if she hadn’t needed a place to go, David admits, he might have fallen in line with other displaced Globeville and Elyria-Swansea residents, resigning himself to leaving the city altogether.

When he was doing a final walk-through of his old home this summer, David found men from H.C. Peck already there. “They were boarding up my parents’ dream home while I was walking through it for the last time,” says David. “It was very inconsiderate.” David asked the men if he could have a few minutes alone.

At that, he remembers, one man placed his hand on David’s shoulder, looked him in the eye, and said, “Get over it. Move on. Start your new chapter.”