Evan Semón

Audio By Carbonatix

This story was originally published on April 4, 2024.

Despite the Colorado Rockies being off to their worst start to a season ever so far in 2025 – just barely beating out the record set last season – fans still pour into Coors Field for games.

After losing nearly 204 combined games in the 2023 and 2024 seasons, the club has struggled to bounce back on the field, but fans haven’t deserted the team yet. The Downtown Denver ballpark the Rockies call home stays filled with fans, even if they aren’t quite as excited as they were when it opened in 1995.

“It’s like getting your favorite toy for Christmas,” Pete Coors, whose Molson Coors company gives the field its name, said of Opening Day in 1995 in the When Colorado Went Major League documentary, which debuted last July.

That year, Major League Baseball started late, on April 26, because of the players’ strike, which had ended the previous season early. The first baseball games at Coors Field were exhibition games against the New York Yankees with replacement players rather than actual Rockies and Yankees.

But April 26, 1995, will always be remembered as the first Rockies Opening Day at Coors Field.

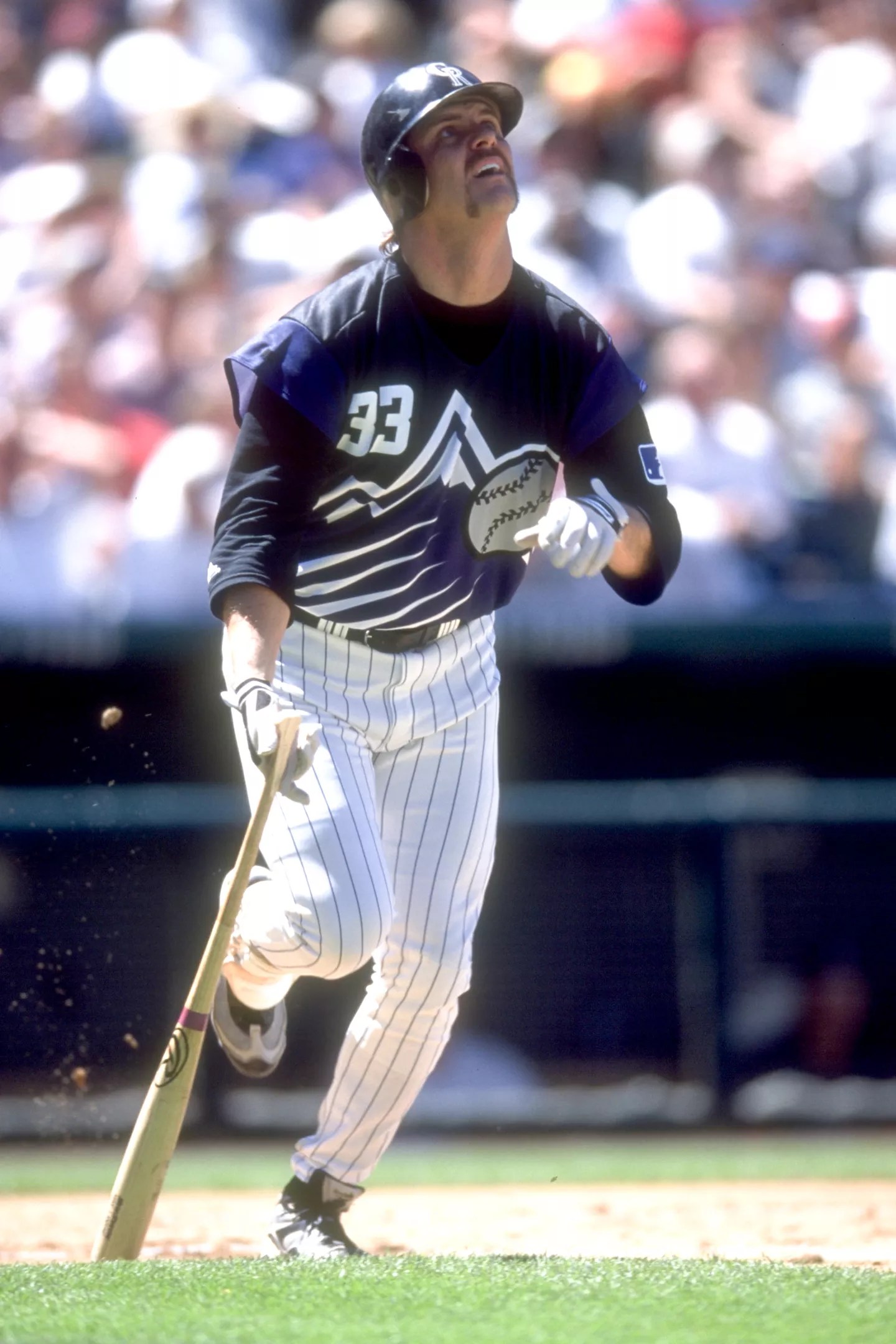

“That’s when Dante Bichette hit a home run in the bottom of the 14th inning to win against the Mets,” says retired Rockies team historian Paul Parker, who was part of the effort to get the team to Colorado in the 1990s.

Building Coors Field was essential to that effort, but it wasn’t an easy path to build the stadium. Twists and turns occurred often, such as Denver County voters opposing the tax that funded the ballpark, a last-second move toward eminent domain to acquire land for the stadium, and dinosaur bones being found during construction.

If You Build It, the MLB Will Come – Even If Denver Says No

Neil Macey grew up in Chicago and worked as an usher at Wrigley Field and Comiskey Park before he moved to Denver and began investing in commercial real estate downtown.

“I love baseball,” Macey says. “My son had just been born in 1985, so I just wanted him to grow up with baseball.”

He worked with others in Denver’s business and baseball communities and then-Mayor Federico Peña, who had campaigned on bringing MLB to Denver, to convince the league to consider Denver as an expansion city. But first they had to build a baseball-specific stadium.

The original idea had been for the baseball team to play at the old Mile High Stadium, but MLB wasn’t interested in putting a team in what had become a football-focused arena – even though it was built for the Denver Bears, which had then transformed into a Triple A baseball team called the Denver Zephyrs.

“We are not going to give an expansion team to Denver unless there’s a new stadium,” Macey remembers being told.

Denver was experiencing an economic depression that began in 1983 and lasted until 1992, however, so professional baseball proponents weren’t sure where they would find enough money for such a big project. But in 1988, 75 percent of Denver voters approved the city’s Scientific Cultural Facilities District, which put in place a one-tenth of 1 percent sales tax to fund nonprofit arts and culture organizations, like the Denver Zoo.

“I saw that and said to myself, ‘Well if 75 percent of voters approve of a tax for the DCPA and the zoo, we can get 51 percent of the people to approve the same kind of tax to build the baseball stadium so we can get Major League Baseball,'” Macey remembers.

After asking around at the State Capitol, Macey found an ally in Kathi Williams, who was a state representative at the time. Although Williams had never been to an MLB game, she had observed other teams threatening to move to Denver as leverage to negotiate better leases in their cities.

“We’d always think we were close to getting a baseball team, but ultimately what would happen is they would renegotiate the lease with their team in their city,” she says. “So this seemed like it was the only hope for getting a Major League Baseball team here.”

She says baseball created a family experience that connected generations and unified communities – all of which she thought Colorado could use. Plus, the Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce had released a study indicating an MLB team could bring $100 million in annual economic development to the region.

“It could rehabilitate a neighborhood,” Williams remembers thinking. “Sometimes that’s all it takes, is a construction project, an investment, to inspire redevelopment in an area. There were a lot of reasons that this would be such a good jump-start for our economy.”

She agreed to run a bill that would refer a ballot measure to voters for a one-tenth of 1 percent tax to construct a stadium for an MLB team, with a provision that the tax would only be collected if an MLB team was actually coming to Denver.

“At that time, the Republicans, we were in control of the legislature,” Williams says. “Tax, of course, is a really nasty word to Republicans, but the love of baseball overcame that particular T-word in their mind, so we were able to pass the bill.”

Governor Roy Romer approved the bill in 1989.

In addition to creating the ballot measure, the legislature had also created a Colorado Baseball Commission in charge of campaigning for the ballot measure and working with the MLB.

The commission had difficulty finding money to finance the campaign, but Denver entrepreneur Bill Daniels eventually gave them $100,000 in funding, and the commission succeeded.

Although voters in Denver and Adams County rejected the ballot measure, Boulder, Douglas, Arapahoe and Jefferson counties had such strong support that it passed with 54 percent of the vote on August 14, 1990. The Denver Metropolitan Major League Baseball Stadium District was then put in charge of designing the stadium and taking care of the physical building, as it still is today.

In December 1990, MLB announced that Denver was one of six finalists for the two expansion franchises it planned to add to the National League. (Miami, Buffalo, Orlando, Charlotte, Phoenix and Sacramento were the other finalists.) That’s when Parker got involved with the effort, volunteering to help sell season tickets to demonstrate support for the team to the MLB. People put down $50 deposits and would get the money back if no team came to fruition.

“That whole thing was way off the charts,” Parker remembers. “We outperformed any kind of expectation and, obviously, we and Miami were the two winners of the franchises. “

MLB approved a team in Colorado on July 5, 1991, which was then named the Rockies. Coors had already been signed to the stadium’s naming rights before the MLB even approved the team.

Many don’t know the story of how Dinger came to be.

Colorado Rockies

Choosing a Site for Coors Field

All six counties in the stadium tax district were allowed to submit potential sites for the stadium. But only Denver, where the tax (and, essentially, the team) were rejected, submitted sites. Along with the 20th and Blake streets site where Coors Field sits, locations where Ball Arena is now and an area just to the south of the current Mile High Stadium were proposed.

The LoDo spot won out partially because the land was cheapest, having been owned mainly by Union Pacific Railroad without much else in the area.

The 22-block LoDo historic district had been established nearby in 1988 to preserve the historic buildings there after 20 percent of them had been destroyed in the 1960s and 70s. The stadium, which broke ground in October 1992, also helped bring new life to the area.

In total, it cost $250 million to build Coors Field, “which doesn’t sound like much these days,” Parker jokes. “It sounds like the price of a utility infielder now.”

During construction, excavators found bones that turned out to belong to a triceratops skeleton, leading to the creation of the Rockies’ purple dinosaur mascot, Dinger. The actual triceratops found at Coors Field isn’t in displayable condition, but a sample of its bones is held at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science.

Unlike most ballparks, Coors Field wasn’t built from the home plate out. That’s because the plot of land where the design team wanted to put home plate was one of only three lots on the property not owned by Union Pacific.

“During the legislative process, my Senate sponsor took eminent domain out of the bill, and what eminent domain is is the right to condemn property,” Williams explains.

Without that right, they couldn’t make the other landowners sell their land for the stadium. However, the legislature went back and added eminent domain to the law in 1993 when it realized the other property owners didn’t want to sell – all while construction in the outfield was ongoing – and then built around to home plate.

Coors Field Becomes a Denver Attraction

The Rockies played their first two seasons in 1993 and 1994 at Mile High Stadium, so fans were already all in on the team by the time Coors Field opened.

It was immediately popular, selling out 203 games straight from June 15, 1995, to September 6, 1997, when the second game of a doubleheader failed to draw a full stadium. That popularity meant the bonds for the stadium were paid off in just eight years despite economist projections of at least twenty.

In 2006, the tax switched over to fund a new Broncos stadium.

The team had a downturn on the field within a few years, unfortunately, which meant fewer people came to games. But Coors Field remained popular, and the Rockies found new ways to attract fans, including eliminating a section of seats in right-center field and replacing them with the now-famous Rooftop deck.

The Turn Ahead the Clock jerseys could be the best uniforms ever sported by the Rockies.

Courtesy of the Colorado Rockies

That decreased the seated capacity by 3,500 and created a standing-room-only area that caters more to social experiences rather than watching baseball. According to Parker, it’s the most significant change made to the stadium since it was built, though the team has kept up with other regular maintenance to keep the field modern.

Coors Field is now the third-oldest stadium in the National League after Dodger Stadium and Wrigley Field, but its popularity hasn’t dimmed with age – or from the lack of on-field excellence. During a 103-loss season in 2023, the average attendance at Coors Field was still 32,197, according to Baseball Reference. That’s seventh in the National League and 14th in MLB.

“They haven’t done much of a job in terms of putting successful and winning baseball on the field, but they’ve done a wonderful job in maintaining a really nice stadium, and for a long, long time,” Parker says.

He admits the team doesn’t have much incentive to change the on-field product if people keep coming, though he does believe the Monfort family, the team’s controlling owner, wants to win, but they just “do not know how.” When the Rockies lost their first game of the 2024 season 16-1 to the Diamondbacks, Parker’s baseball friends blew up his phone lamenting the team.

“In the third inning of game one of the season and it’s ten to one, Arizona, my friend texts, ‘Will this season never end?'” Parker shares. “So it’s come to that.”

Why Still Go to Games When the Rockies Are Bad?

As Macey points out, baseball has always been about more than just what happens in the game. It’s about chatting to others in the stands or walking around the park to catch views of the excellent Colorado sunsets.

“You’ve got some time you could interact with people, interact with your family,” he says. “It’s a totally different experience than the other sports.”

Additionally, Parker says, the Rockies have always worked to make coming to Coors Field an experience with a pleasant atmosphere and plenty of baseball nostalgia.

“You’re not around too many belligerent drunks, and it’s a place you can take a family and not have to get a second mortgage,” he adds.

The legislation for the stadium required some seats to remain affordable no matter what, so the Rockpile – known for its cheap seats, stiff backs and sunburns – is here to stay.

Plus, the thin air in the Mile High City really makes balls fly, so there’s always the chance of a record-breaking home run. The average Coors Field home run traveled 421 feet in 2023. Nolan Jones of the Rockies hit the third-longest home run of 2023, good for 483 feet at Coors Field, and four of last year’s top-ten longest dingers were hit at Coors Field.

Williams and Macey raised funds and hired local filmmakers Kyle Dyer and Julie Andrews to produce When Colorado Went Major League and released it for free, because they want more people to know how the stadium and team came to be.

“It was the community, and community spirit, that made Major League Baseball happen here in Colorado,” Williams says. “Coors Field is something that, regardless of what the Rockies win-loss record is, is a great asset that belongs to the community.”

Williams and Macey attend every home opener together each season. They love seeing the excitement of the crowd and the overflowing bars near the stadium, and the pair always walks around the ballpark a few times before the first pitch to enjoy the atmosphere.

“I remember getting one call where a person said, ‘You’re going to build a white elephant,'” Williams recalls. “If this passes, nobody’s going to go to a baseball game. This is a football town. All you’re going to do is build something that is going to become a ruin. That, certainly, thank God, hasn’t proven to be true.”