Catie Cheshire

Audio By Carbonatix

Candles and flowers still cover the pavement outside Sol Tribe Tattoo & Piercing at 56 Broadway, and the smell of palo santo and sage continues to waft through the air. Every now and then, more mourners stop by. They are here to honor the shop’s proprietor, artist/activist Alicia Cardenas, as well as its jewelry manager, Alyssa Gunn-Maldonado. Both lost their lives in a crime spree that left six dead, including the killer, and two injured.

On December 27, 2021, former tattoo shop owner Lyndon McLeod made good on his fantasy of murdering several people – some of whom he knew from the tattoo industry, others with connections yet to be revealed. His victims included Cardenas and Gunn-Maldonado, as well as Danny Scofield, a tattoo artist who was at Lucky 13 Tattoo in Lakewood; Sarah Steck, an artist who worked at the Hyatt House in Belmar; and Michael Swinyard, who was killed at his Cheesman Park apartment. James “Jimmy” Maldonado, a piercing artist who was married to Alyssa and was at Sol Tribe that day, and Ashley Ferris, the Lakewood police agent who fatally shot McLeod, were both injured.

This wasn’t the first tragedy to stamp an indelible mark on Denver’s tattoo scene. But the members of this stalwart and tight-knit community are determined not to let violence define an industry that has worked for generations to reach the point where it is now: an amicable, neutral environment where clients can get art that is healing, creative or simply fun from tattoo artists of any race or gender identity.

Tattoo artists have a strong appreciation for their industry’s deep roots, and its history in Denver is particularly rich, filled with urban myths and legendary figures who transformed the art form: gangsters, bikers and outlaws who demanded a fierce sense of loyalty fifty years ago. But that began changing in the ’90s, as the city’s population boomed and new tattoo shops opened with artists who wanted to make custom pieces rather than the more prevalent flash art.

Cardenas was in the lead of this new generation, creating more inclusive environments that stood apart from the biker gang and drug-dealing affiliations with which the industry had been branded for decades. Sol Tribe was a place of ritual and healing that honored tattooing’s origins in Cardenas’s Indigenous heritage. “We’ve come a long way in thirty years,” she said last month, in what may have been her last interview before she was murdered.

Kim Schaefer at Denver City Tattoo Club.

Courtesy of Denver City Tattoo Club

Denver City Tattoo Club could be a museum of Denver’s tattoo history. Nikolas Pew, who opened the shop at 3451 Larimer Street in 2017, has covered the walls with flash by legendary artists from this city and beyond. Pew got his start in tattooing at a young age; family friends Greg and Peggy Skibo, the owners of shops in Cheyenne, Greeley and Fort Collins, showed him the ropes decades ago.

“There is history on these walls,” Pew says. “There are certain artists who are from Denver or spent time in Denver who are special to me. I wanted to make sure to find a home for those pieces, because they’re relevant to what I’m trying to do with this studio.”

The walls feature flash from many gape-worthy artists: Rex Ross, Mickie Kott, Edward Lee, Peter Tat-2 and David Gibson, whom Ross taught. “Gibson is considered one of the all-time greats, a legend,” Pew says. “Rex was Dave Gibson’s mentor. A lot of people don’t know that he started tattooing in Denver. He became a very well-known and respected tattooist; he was a really good sign painter, too, and he lettered the windows at Peter’s shop.”

Flash, particularly that of the caliber on Pew’s walls, became popular again as tattoo artists and clients began exploring the industry’s history and roots. Pew compares it to music: Even as new genres emerge, people always seem to acknowledge and have an admiration for the classics.

But no one appreciates the past more than Pew. “Red Gibbons is one of the earliest tattooers to have a shop in Denver, back in the ’30s,” he says. “He tattooed out of an arcade on Curtis Street, and he was the husband of the most famous tattooed woman of that time, Artoria Gibbons.” He also recalls R.J. Rosini, who tattooed in Denver in the ’70s and ’80s with his partner “Sneakin’ Deacon,” whom Pew describes as “a biker poet and tattooer, kind of a Kerouac of the tattoo world; he made several books.”

Omnipresent in those early days were other outlaw types, including notorious Denver tattooer Edward Lee. “His flash was very ‘hot’ for how young he was; his style was very much influenced by Frank Speaker and Mickie Kott; they kind of took him under their wing,” Pew says. “His art had a punk rock/biker element to it – really cool ’80s-style stuff. He ended up going to prison for a very long time for murdering somebody. I think the tattoo community embraced him because he was an outlaw; he got into tattooing at a very young age, and he could draw.”

Mickie Kott was one of the female artists who got her start in Denver. “She teamed up with legends Greg Skibo, Frank Speaker and Edward Lee to form Metro Tattoo around 1990,” Pew says. “That shop was firebombed by a jealous competitor. After that, she reopened as Tattooing by Mickie.”

The most infamous tattooer of all is depicted in a prominent photo in the studio, grinning between three topless women posing on a leopard-print blanket. “That’s Peter Tat-2,” says Denver City Tattoo Club’s Kim Schaefer. “And that woman there is me.”

Peter “Tat-2” Poulos worked to change the tattoo industry’s reputation not just here, but in Long Island and Phoenix. Schaefer works at DCTC because it reminds her of Poulos’s shop at 1118 Broadway, where she first cut her teeth in the business 45 years ago. “The reason I came back here is because Nik knows the past,” she says. “Peter would have loved this place. I learned how to tattoo off these very sheets.”

Schaefer had been studying to become an educator at Western State College when she first walked into the Broadway shop in the late ’70s, and Poulos marked her with her first tattoo: a butterfly. He later asked her to work for him. Poulos’s crew – known as the Peter Tat-2 Association – was very exclusive, and you could tell who’d been welcomed into it by the snake tattooed on their left hand. His partner, Larry Romano, was known as the muscle of the operation.

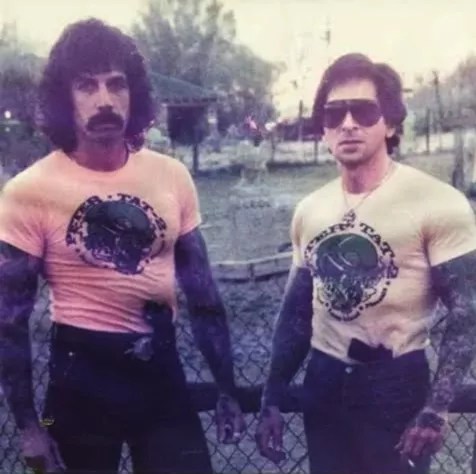

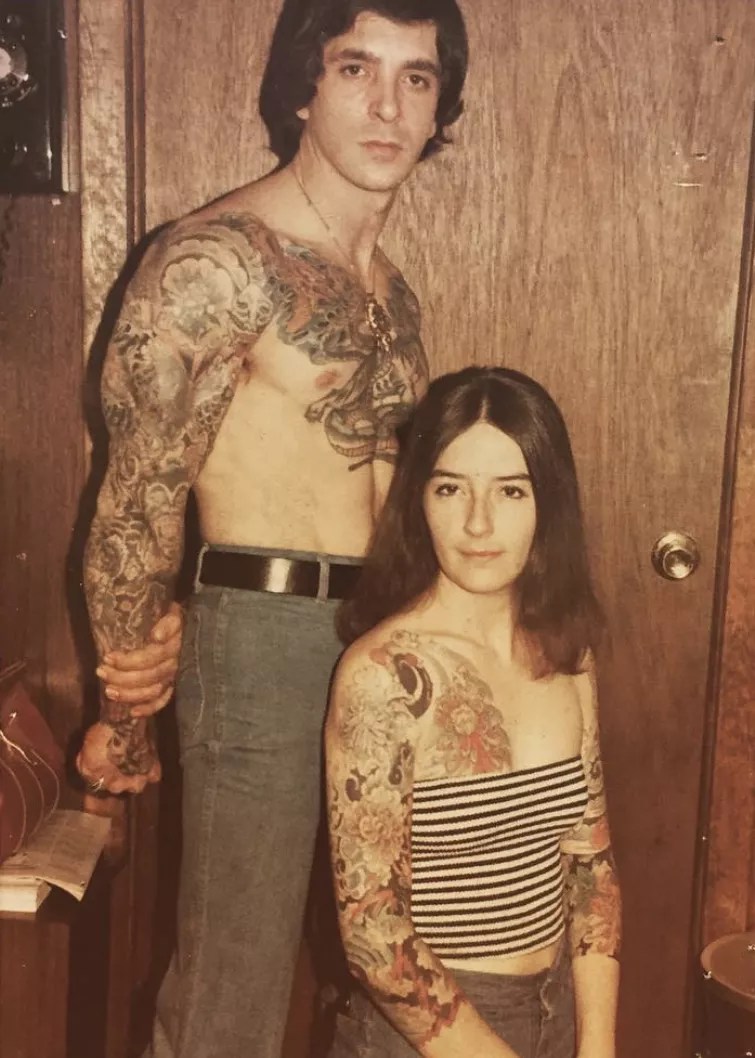

Larry Romano and Peter Poulos were titans of the tattoo industry.

Courtesy of Ryane Rose

“Peter came to Denver from New York and was trying to change the image of tattooing so it wasn’t just convicts. I think that’s why he hired girls, mostly, to work. And we had to be really good girls, too,” Schaefer recalls. “We couldn’t be drunk and running around – there was a certain thing he wanted to portray. … Peter didn’t let us have boyfriends, really. He didn’t want any scumbags. He was really picky about shit.”

At 66, Schaefer is still an undeniable beauty. Her expressive brown eyes are underscored by heavy, tattooed eyeliner; she has a rose tattooed under her right eye and cascades of thick silver hair. She was one of many women Poulos hired at a time when women weren’t often seen as part of the industry. “I haven’t done an interview since the ’80s,” she admits.

“There’s been a lot of talent in Denver over the years,” Pew says. “Everyone kind of wanted to be friends with Peter. He was very influential; he worked hard to become a really good tattooist – one of the best. That is Kim’s lineage. There have been a lot of fantastic women tattooers who have called Denver home, and I think that’s really special – not that it’s totally unique to us, but it is something that is prevalent here.”

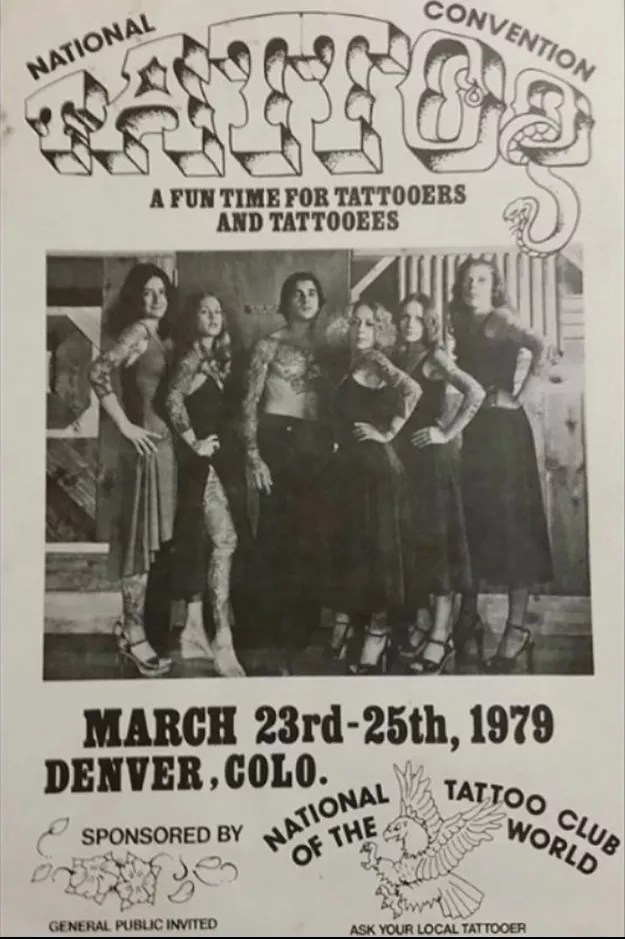

Inspired by nationwide tattoo groups in Scotland and Japan, Poulos and his wife, Dyane, were influential in founding the National Tattoo Association (then called the National Tattoo Club) with other leaders of the industry, including Eddie Funk – known as “Crazy Philadelphia Eddie” – who served as the group’s president. Poulos and his wife hosted the first convention in 1979 at the now-defunct Cosmopolitan Hotel in Denver. Although tattooer Dave Yurkew had held earlier conventions, the Pouloses and others decided to reboot the industry with their own.

A flier for the 1979 National Tattoo Convention.

Denver Tattoo

“Because of the people who were involved, all the greats and big-time artists, all the old-school guys, all the new guys – anybody who was anybody came,” Pew recalls. “Peter and his wife really had that influence, even though he was a newer-generation tattooer at that time. He had the pull to call on these guys, and people knew who he was. He was able to get everyone involved. That was a real turning point in tattooing, and it just happened to be in Denver.”

But the power of the Pouloses was not an accident. “Dyane and Peter were together from an early age; they grew up in Brooklyn, and in my opinion, she was a big part of his success,” Pew says. “They had humble beginnings, and her business sense, vision and no-bullshit attitude, along with Peter’s talent, shaped the PTA into what it ultimately became. She was pretty, petite and could be sweet as pie, but if you crossed her, you would suffer for it. She had the type of personality that demanded respect; she had no remorse for anyone who betrayed the association. She taught the other girls at the shops how to carry themselves with class, integrity and, if need be, how to go into battle with a full heart to destroy anyone that got in their way.”

Dusty Ullerich also witnessed the early days. His father, Paul Ullerich, was a Denver tattoo artist who’d been taken under Poulos’s wing and became part of the National Tattoo Association. “In 1978, my dad didn’t want to upset Peter and get into any tattoo war with him, because that would be a losing cause,” he recalls. “Since they were already buddies, he asked Peter if he could take over an existing shop instead of opening a competitor shop. That’s when he started the Emporium of Design.”

Ullerich was six. “I rode there in the bus after school every chance I got, and the next thing you know, I was earning my allowance money building needles and mixing ink,” he says. “I actually built needles for a lot of other tattoo shops in town.”

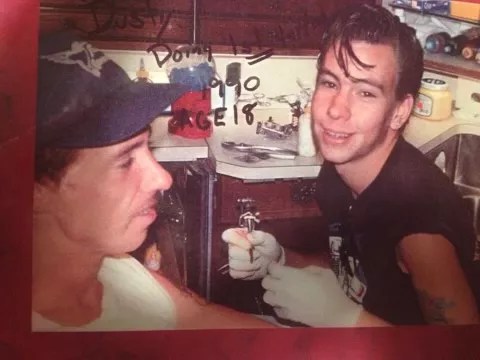

Dusty Ullerich’s first day on the job, New Year’s Eve 1989.

Courtesy of Dusty Ullerich

The National Tattoo Association is still around, but it no longer holds conventions – largely because tattoo conventions are happening weekly all around the country, Pew says.

Schaefer’s business cards read “Tat-2 Kim, formerly of Peter Tat-2 Studio.” She says there aren’t many tattooers like her anymore: people who trace flash and don’t draw their own, but to whom tattooing is part of their nature. And she talks about some dark times with a sunny outlook.

“Peter was kind of a controlling person,” she says. “He had some heavies working for him, but they were all friends of his, and he was just trying to give them a chance. People who didn’t have anything. He’d teach them how to tattoo. It was working out pretty good until he started getting into some crazy shit. … He left one weekend and he never came back.

“He got shot and killed on May 26, 1983. He was 36,” she says. “It was five days before my 28th birthday. It was awful.”

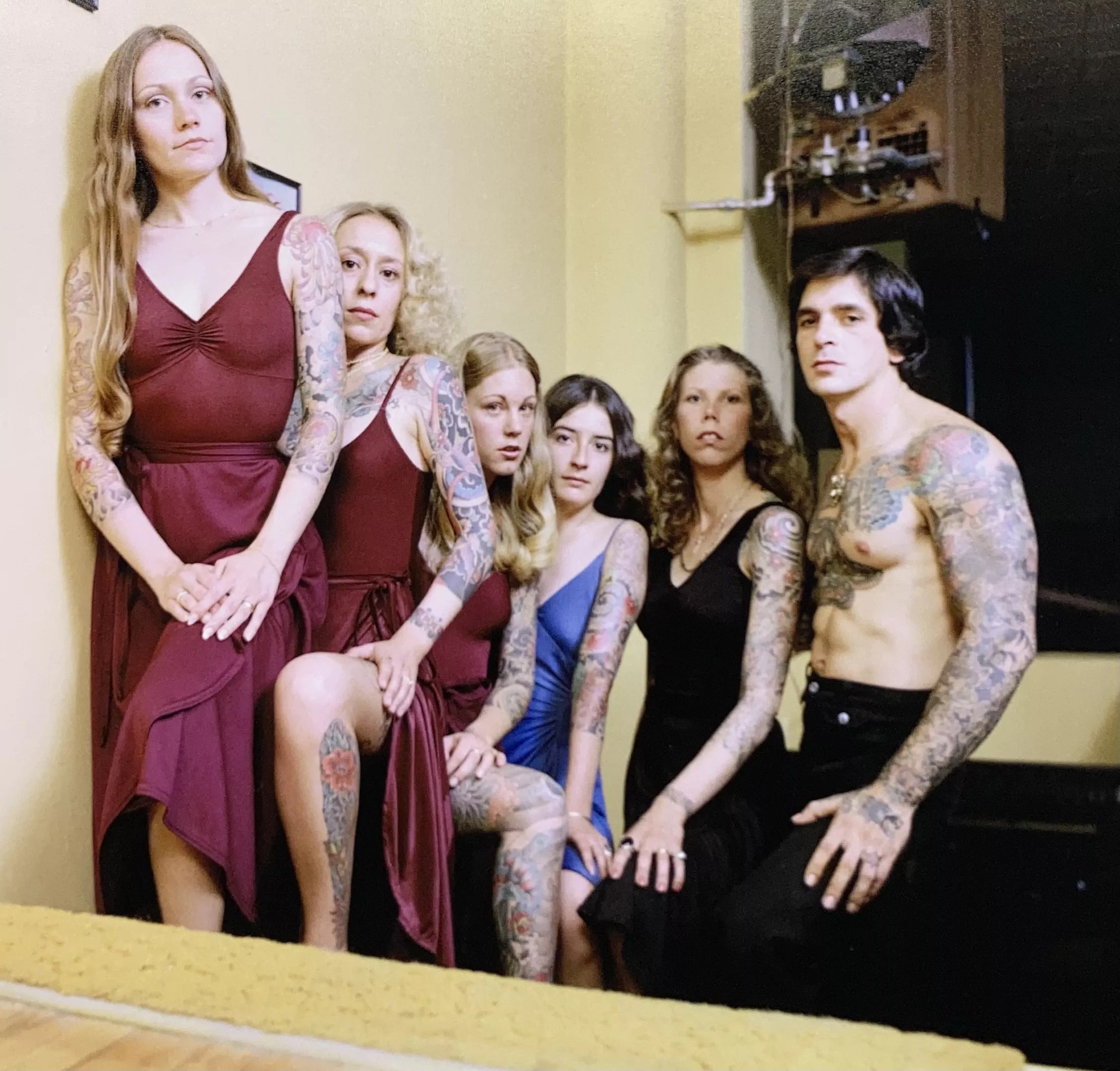

Peter Poulos with friends and employees Theresa Hannong (from left), Dyane, Barbara Chapman, Kim Schaefer and Peggy Skibo.

Courtesy of Denver City Tattoo Club

The killing of Poulos hit Denver’s tattoo community hard, and it inspired many urban myths: that he was blindfolded and taken out to the desert in Arizona, where he was executed over a drug deal gone wrong; that he was taken out by a greedy associate.

Pew brings out a 1983 cover story from Westword sister paper Phoenix New Times. It has an interview with the killer.

Peter Poulos and Kim Schaefer in the early days.

Denver City Tattoo Club Instagram

The first of the brittle pages, yellowed and curled at the tips, shows a woman screaming the words “Weirdos!” and “These guys make me puke!” Inside is a dark story detailing how Poulos, his wife and two others had gone to Phoenix to collect $4,600 from a man named Jeffery Sam Dawson, an amateur tattoo artist who had taken two ounces of cocaine from Poulos. “Dawson was an entry-level tattooer, a thug with ties to the outlaw-biker scene,” Pew says. “Peter tried to teach him to tattoo, but he had no talent for anything but finding trouble.”

Poulos entered the house while his wife and friends remained outside. Dawson, who’d noticed that his house had been broken into earlier, was ready with a double-barrel shotgun. Poulos came through the taped-shut window, saw Dawson and told him, “Well, you better shoot.”

Dawson, who said that he thought Poulos’s intentions ranged “anywhere from breaking my arms and legs to killing me,” proceeded to shoot Poulos in the hand and, as Poulos continued moving toward him, shot him fatally in the chest. As Poulos’s cohorts hopped in their car and took off, Dawson yelled to his neighbors to call the police: “I’ve just shot someone for trespassing.”

Dawson, who was protected by Arizona’s “Make My Day” law, went into hiding; he was afraid Poulos’s loyal “Tat-2 Mafia” would hunt him down. “You could feel the heat when you were around him,” Dawson told the reporter. “If you talked to him, he could be the nicest guy in the world. Then he could change from night to day and do it on a dime.”

Schaefer says that she knew Dawson before the killing, but never heard from him afterward. Romano immediately took over the Peter Tat-2 Association businesses.

Schaefer left the shop after Romano took over. “He was scary; he was fucking crazy,” she emphasizes. “I wasn’t sticking around. … But I was looking over my shoulders forever, because you weren’t supposed to leave the company. There was an ownership thing back in the day; it was Tat-2 Mafia. But I can’t talk about a lot of that. I know too much shit from the past.”

In fact, Schaefer left Denver and quit tattooing for a while before opening a shop in Durango in the ’90s and then in Buena Vista. She returned to Denver to work with Pew when he opened his shop in 2017. “After Peter died, everybody started going crazy again with firebombing and other bullshit and trying to take power, from the ’80s to the ’90s,” Schaefer recalls.

Violent competitors weren’t the only problem during this era. As the AIDs epidemic swept across the U.S., tattooing became embroiled in a catastrophic health crisis. The National Tattoo Association worked with health departments to create sanitation protocols, which were adopted nationwide as the business became more professional than ever before.

Sol Tribe owner Alicia Cardenas.

Jake Cox

Alicia Cardenas grew up in Denver and started tattooing at a young age. Early on, she became involved in the industry’s emphasis on safety and health regulations. She was an instructor for the National Safety Council for twenty years, teaching classes about bloodborne pathogens, and served on the board of directors for the Association of Professional Piercers.

But she was looking at other changes, too. She wanted to make the industry both more inclusive and more creative. After working at multiple shops where she couldn’t find the artistic atmosphere she sought, she opened her own shop, Twisted Sol, in 1996.

“In the late ’90s, we decided that we were gonna do shops with no flash on the walls – we were going to take it into this new, artsy realm,” Cardenas recalled. “We were just going to do only our own art and draw things for people instead of making them choose things off the wall. And with that, we also wanted to bring more of a marriage of body piercing and tattooing together. … It was in the late ’90s that we rebirthed shops that had more to them, more stories – I would say the modern primitives, the tribal aspect that we were more culturally respectful. We were talking about doing things for other reasons than being a rebel or being sexual. We explored all the subcultures of people we could have as clients. It was no longer about if you weren’t cool enough or tattooed enough. You wouldn’t walk into the shop and be scared away; you were welcomed in.”

Sol Tribe offers piercing and tattooing.

Jake Cox

John Slaughter, who founded Tribe Tattoo in the Art District on Santa Fe 21 years ago, was another artist who emerged in the ’90s with a desire to change the tattoo environment, though he certainly respects its history. His shop has a different feel from DCTC’s vintage vibe. Oldies play over the speakers, muted TVs show various programs, and artists perch on velvet cushioned seats while they design new work. Slaughter smudges the space every day with sage.

“I got my first tattoo in my best friend’s basement when I was thirteen,” he recalls with a laugh. “I got an ankh, and it somewhat resembles one, but I got in the car and my mom was like, ‘You’re an idiot.'”

The friend who tattooed him that day ended up working for the Tat-2 Association. “They pretty much revolutionized tattooing,” Slaughter attests. “Peter actually started mixing colors, changing up the entire game of tattooing. Instead of just red, yellow, green, blue, he started mixing and doing shading and bringing tattooing into life.

“But Larry was mafia. When he knew you opened a shop, they would come and demand a percentage, or they would blow up your shop, or they would hammer your hands and you would never tattoo again,” Slaughter adds.

When he met Romano, “I was a little scared,” he admits. “But we hung out and got along really well.” In fact, Romano offered Slaughter a job at any of the Tat-2 Association shops in Phoenix, New York or Denver.

“I was like, ‘Dude, I like you, but I would never work for you,'” Slaughter says. “And he respected people like that.”

Slaughter says that he knew people whose hands were hammered and whose shops were bombed. “It happened all the time,” he recalls. “That’s why there were only a couple of shops back in the day. Everyone was scared of Larry; you didn’t mess around with him. He would find you in a dark alley, and that would be it. He owned you. And that was scary.

“Back then, that was the tattoo world,” Slaughter continues. “If you wanted to be a part of it, you had to get marked, and he owned you. Back in the day, it was flesh and blood to be a part of this.”

Slaughter and Cardenas were among the artists working to change that. “It’s not like back in the day, where you didn’t mess around with tattoo shops or you’d get your ass kicked,” Slaughter explains. Now the clientele has shifted to everyone from doctors to priests to celebrities: Slaughter says he has tattooed most of the Denver Nuggets players.

There’s been a shift not just in who gets tatted, but in who does the tattooing. “I don’t think anyone would even consider getting a tattoo from a gay person back in the day without that person being beat up or something. It was such a highly male-dominated, crazy world back then,” Slaughter says. “Now it’s more about the art, the people expressing themselves outwardly instead of just being a tough-guy thing.”

John Slaughter is still in the business.

Courtesy of John Slaughter

Slaughter sees tattooing as a spiritual practice, and he encourages his employees to take the same view. He’s a Sundancer and has been praying with the Lakota Indians for over three decades; he honors the Indigenous roots of tattooing, referencing how historically, shamans were the only ones considered spiritual enough to mark someone for life.

“Not anyone can go and mark someone forever, and that’s what I tell people who come to me,” he says. “You have to be that sacred person and walk on that road with the person you’re tattooing in that good state of mind. And that’s a hard thing, because we’re all human, too.”

Slaughter and Cardenas had been friends for years. “I knew her since she was a kid,” he says. “If you don’t know Alicia or at least know of her, then you’re not a part of this community. … I remember Alicia telling me when I opened my shop: ‘Good for you. There’s enough to go around.'”

That in itself was a signal of a new era for tattoo shop owners, he says.

“She didn’t say anything negative about me opening,” he remembers. “There’s enough to go around, there’s a lot of people around here. But you have to be respectful of your community or you’ll get rocks thrown at your window. A lot of these kids, they don’t want to put the time into it. … If you want to be a part of this, there’s some old-school stuff and logic that has to stay and won’t go away.”

That doesn’t mean it can’t be improved, however. In December, Cardenas spoke of the importance of respect in the industry, including giving existing shops a heads-up before moving your own shop in down the street. “Those types of things are really lost in this coming age,” she said. “Part of integrity is about knowing where you fall in it all and having a good understanding of who all is around you.”

Cardenas was also working to “rewrite the apprenticeship model” so that more people of color would be included in the business. Too many apprentices were treated terribly and went unpaid for years, she said, making it difficult to enter the industry if you were in difficult economic circumstances, the sort that people of color statistically endure.

“I have been building my tattoo shop vision since day one about making a space that was more inclusive and more friendly to different walks of life, the queer community – taking it out of the biker, prisoner sort of realm and getting it into a space where anyone who wanted to could walk in and get a good tattoo and feel comfortable,” she said.

“And that’s really what it’s about,” she continued. “Taking it out of this history of bad behavior that’s undeniable when you have a whole industry born off of people who come out of prison or who have embraced this alternative lifestyle – there’s gonna be drugs and misogyny and abuse. But the part where it’s been reborn, where people who are nonbinary have a voice – that’s been going on for a while, that’s been manifesting and switching and evolving for at least the last 25 years.”

Still, she noted, full inclusivity also allowed more traditional, macho parlors – what she called “good ol’ boy shops” – to stay around, even if some industry newcomers dislike them. “Maybe it’s because I’m almost fifty, but it doesn’t bother me, because people need what they need from tattoo shops,” she said. “Magic happens in those studios, too.”

Ryane Rose just opened Wolf Den.

Courtesy of Ryane Rose

The Wolf Den just opened on East Colfax Avenue this fall. It’s owned by Ryane Rose, who is nonbinary and only hires women tattoo artists with the goal of fostering a safe, therapeutic and nurturing environment. The shop created a visual arts gallery in its foyer to extend its reach to local artists who may not be making the cash that tattoo artists can collect.

Despite all of the progress in the industry, Rose still sees a misogynist cloud hanging over the industry, with owners who aren’t willing to let go of toxic traditions like harassing new shops or hazing apprentices.

The tattoo culture is “really aggressive,” Rose says. “It’s still a hard barrier that I’m gently trying to break. The mentality was, ‘If you take this client from me, then you’re taking food from me.’ No, there’s enough for everyone. That’s why I named this the Wolf Den. We will all eat if we work together. We’ll eat more, we’ll eat better, we’ll eat more frequently.”

This is Rose’s third iteration of the Wolf Den, and even before it opened in a space once occupied by another tattoo parlor, all of the materials were stolen. “The landlord forgot to change the locks, and the artists who owned it before came in and stole almost all our things,” Rose says. Then someone threw rocks through the window.

That was mild compared to Cardenas’s recollection of being beaten with a pistol and having her shop shot up in the ’90s, or Schaefer and Pew describing how Kott’s shop was burned to the ground by competitors. But to Rose, the actions still signaled that changes had to be made.

Before opening the Wolf Den, Rose worked at the newer Peter Tat-2 location on East Colfax for a while. “I tried to get hired at Sol Tribe, and Alicia said I was too green,” Rose recalls. “I went to Fallen Owl, and they said the same. But they were very encouraging.” Rose finally answered an ad for a shop manager on Craigslist and was hired at All Heart Industries in 2015.

That’s the tattoo shop at 246 West Sixth Avenue that was owned by Lyndon McLeod, who committed the December 27 killings. He shot up that address, too.

“The detective I spoke to was floored,” Rose says. “Lyndon was alone. He has no loved ones, nothing. No one who he tattooed has come forward to talk about him. The detective said they are just trying to put the pieces together of how perplexed and how narcissistic this person was. And he made the puzzle hard for a reason.”

When Rose got the job, McLeod said the responsibilities would be managing the shop, hiring artists and taking over day-to-day operations. But soon McLeod cut off communication and would often speak to Rose through an assistant, “who always seemed to be scared,” Rose remembers.

McLeod was condescending and called himself a writer. “He would speak in very ambiguous riddles where he wanted you to ask more questions, but I just never did,” Rose says. “He was always wearing black and tactical clothing. He’d have his shirt tucked into his cargo pants, and he always had a gun. He would always allude that there was more weaponry in his car, which was matte black and tinted.”

Rose remembers him saying, “You can run my shop, but just don’t ever touch my shit in the back.”

The back room was painted black and decorated with bones, feathers and other morbidities. One wall had a ledge on which McLeod would stack candles, burning them until they melted into a tower of wax on the wall. He also had some impressive books – “heavy literature like The Communist Manifesto and The Masterpiece,” Rose remembers – that he would relabel with new titles: “I think he thought he was better than the writers and could name the books better. He Sharpied out the title of The Masterpiece and renamed it ‘The Works.'”

But then Rose noticed that McLeod’s personal bills were all going to All Heart, and the cash flow wasn’t adding up. “I know at that time he was making a lot of money illegally growing weed,” Rose attests.

And one day, the health department did a run-through. Rose recalls the department inspector asking how long the shop had been there and noting that it was violating zoning and licensing laws; McLeod hadn’t renewed his license, despite his proclamations otherwise.

Rose left to work at Peter Tat-2, and remembers McLeod continuously calling in threats. But that was part of the usual pattern for the industry. “To this day, when I have hired a new artist, their old bosses will harass them for about a month and then let it go,” Rose says. “So I’ll bet the owner of Tat-2 at the time didn’t bat an eye. But I came to find out Lyndon meant everything he said.”

After McLeod lost All Heart, Cardenas briefly expanded her shop into the space before opening Sol Tribe on Broadway. According to Rose, McLeod had said that he’d tried to do business with Cardenas in the past and she’d turned him down. It had enraged him, and he remained furious.

Denver detectives have been going through McLeod’s writings, which reveal a bitter, outraged man who believed intensely in male supremacy and alt-right philosophies. McLeod wrote three books in which a character sharing his name has a mission to murder 46 people, and goes into a tattoo shop and kills a woman named Alicia Cardenas and a man named Michael Swinyard. Rose says the detective mentioned that other names have been coming up as well.

Rose was out of town on December 27 when an alarm at the shop was triggered; there was broken glass and what appears to be a bullet hole in the frame of a shop window. “The police can’t definitively say anything, but it was two hours before the shootings took place, and Lyndon called my shop twice,” Rose says. “The detective told me, ‘All I’m going to say is that you are very lucky you weren’t in town that day.'”

The tributes continue coming to Sol Tribe.

Patricia Calhoun

On January 16, tattoo shops across Denver held fundraisers to share art and memories of the victims. “The tattoo community is so close,” says Stevi Miller of Modified Madness Tattoo, who organized the benefit. “We’re enemies, but we’re not enemies. You don’t want your client going somewhere else, but when something like this happens, we come together.”

Indeed, the tattooing community has come together like never before. “We have to,” Slaughter says. “It happened at King Soopers. I don’t think it’s a tattoo thing; it’s some fucking psycho asshole who came in and murdered innocent people. You could be buying groceries, you could be pumping gas, and that’s the scary thing. I tell everyone don’t be afraid, because we can’t live life paranoid. If it’s going to happen, it’s our time, I believe, and there’s nothing we can do. But we can’t hide in our houses.”

“I hope to see the tattoo community as a whole coming together as a united front as opposed to the unnecessary and unhealthy competitive nature it was born in,” adds Rose. “I feel this really opened our eyes to something I’ve felt in our creative community for a long time, and that’s mental health and hate. I hope in the future as artists, we acknowledge we are vulnerable humans who should prioritize our mental health. As a community, we can hold each other and ourselves accountable, which hopefully will prevent something so horrendous from happening again.”

Ullerich, who took over Emporium of Design when his father died in 2011 and later merged it with his own shop, Kool Kats, still misses the “rugged individuality” of the ’80s.”There was mad respect in the industry back then,” he says. “Now there are so many people who don’t know each other or their history. When we talk about the tattoo community being a tight-knit group, that’s true to an extent, but there’s a big element out there that doesn’t keep in contact with each other. The roots on the tree have spread out as it’s gotten bigger.”

But even he notes positive changes, including the quality of the artwork. “An old famous tattooer from San Francisco would say, ‘Tattooing is old as time and as new as tomorrow,'” he recounts. “And that’s really the way it’s evolved.”

Says Rose: “There is room for everyone. I think it’s important that as artists we all respect one another and acknowledge how our industry didn’t set us up for success in regard to working alongside each other in the industry. However, we can change. We’re all artists; we’re feelers. We’ve all dedicated our lives to enrich happiness, visually and spiritually.”

“The tattoo world has always been a really strong, tight-knit community. Even if we don’t like each other, we still know that each other are there. … All we can do is just move on and try to be good people and try to treat people with respect,” Slaughter concludes. “And try to love ourselves, too. If we can do that, then we can manage everything else.”