Michael Emery Hecker

Audio By Carbonatix

If there’s one thing it seems like 2020 Democratic presidential hopeful John Hickenlooper wants you to remember about his time as governor of Colorado, it’s the methane rules.

In 2014, Colorado became the first state in the country to enact regulations requiring oil and gas companies to limit the amount of methane – an especially potent greenhouse gas – that leaks out of the wells, tanks, pipelines and other facilities that make up its supply chain. And as Hickenlooper tries to convince an increasingly climate-conscious Democratic base to help send him to the White House, he doesn’t want anyone to forget it.

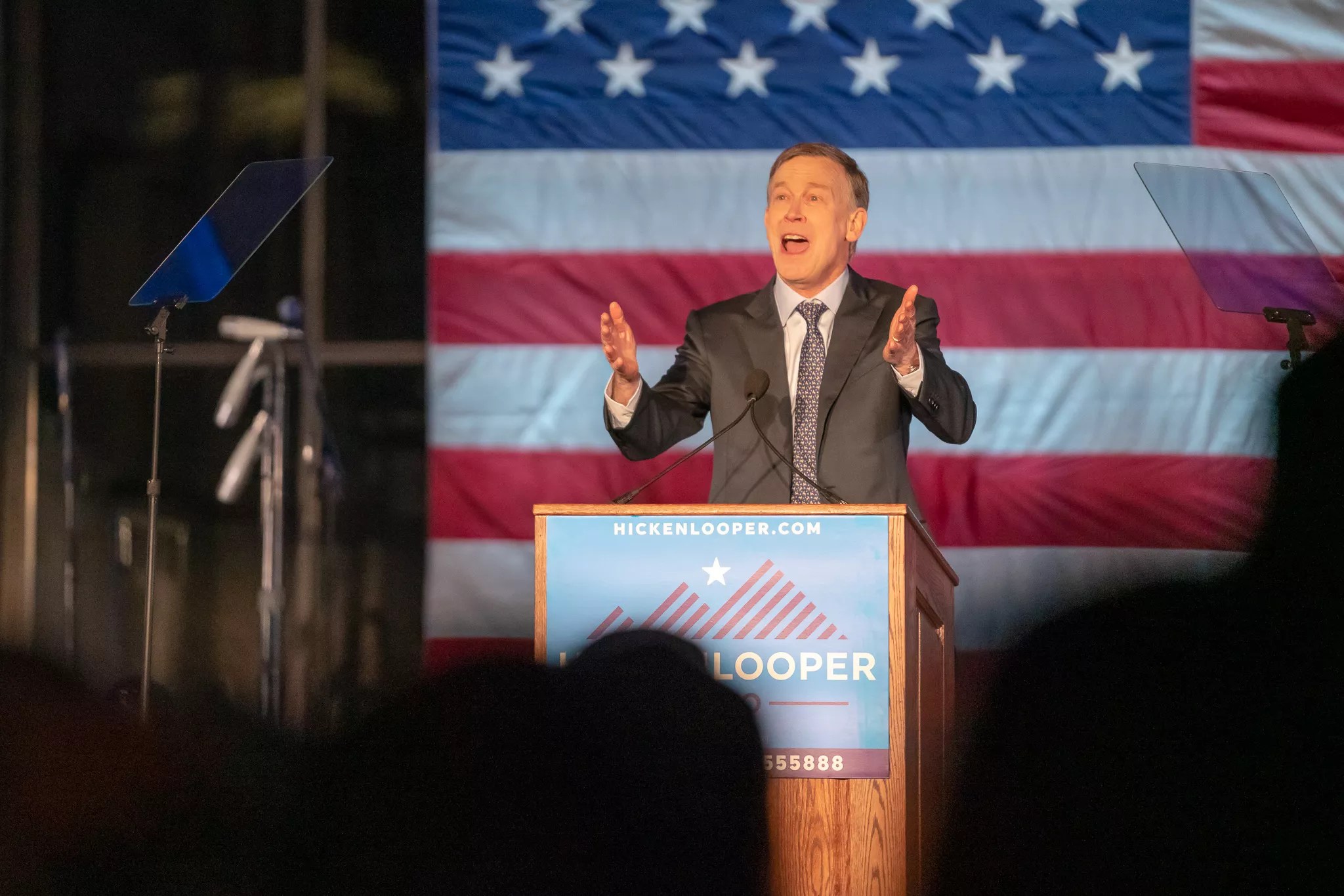

In his announcement speech in Civic Center Park in March, he listed the methane rules among his top policy achievements. He’s touted them in his campaign launch video, his CNN town hall, in dozens of other TV appearances and stump speeches, and in his campaign’s official climate-change plan, which promises to use the rules “as the model for a nationwide program” to reduce emissions. It’s a safe bet that he’ll bring them up again tonight, June 27, as he makes his pitch on stage at the first Democratic primary debate, in Miami.

The methane rules have become much more than just another feather in the former governor’s cap. They’re central to the theory of political change that Hickenlooper has been articulating on the campaign trail – his belief that meaningful progress comes not from beating the drum for radical transformations like the Green New Deal and Medicare for All, but from bringing opposing sides together and hammering out a compromise.

“Colorado was the first state to compel the oil and gas industry to eliminate methane emissions. We didn’t get there with socialism,” reads a graphic that Hickenlooper’s Twitter account sent in reply to Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, his primary rival and a self-described democratic socialist, earlier this month. In a Washington Post op-ed in March, Hickenlooper bashed the Green New Deal and pointed to the methane rules, enacted “by working with both environmentalists and industry,” as a model for effective policymaking on climate issues.

There’s only one problem for Hickenlooper as he travels the country promoting Colorado’s methane rules as a bold climate solution: Among climate scientists, activists and policy experts, the regulations have become something of a punchline.

“When you look at overall carbon emissions in Colorado, methane emissions are a drop in the bucket,” says Jeremy Nichols, director of the Climate and Energy Program at environmental advocacy group WildEarth Guardians. “And even that’s pretty generous.”

The natural gas extracted from deep underground by the oil and gas industry is composed chiefly of methane, an especially powerful greenhouse gas that leaks out in the process of drilling, storing, processing and transporting the gas. Even a leakage rate of 2 to 3 percent, which studies have estimated as the industry-wide average, could be devastating for the climate in the long term.

Regulations that seek to limit methane leakage throughout the oil and gas supply chain are an attempt to minimize those climate impacts. But even if those leaks were somehow completely eliminated, all the extracted oil and gas would still be flowing downstream to be burned as fuel in cars, power plants, heating systems and more – releasing vast quantities of the most common greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide, into the atmosphere. And the impacts of all that CO2 far outweigh the effects of methane pollution.

In 2014, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment estimated that direct methane emissions from oil and gas activity in 2020 would amount to about 13 million tons of CO2-equivalent (CO2e), a metric used to compare the warming effects of different greenhouse gases. Thanks to Hickenlooper’s methane rules, enacted by state air regulators that same year, that figure is projected to fall to about 8 million tons of CO2e, according to an analysis by environmental group Western Resource Advocates.

To put that into perspective, Colorado’s total statewide emissions are currently estimated at over 130 million tons of CO2e per year. And because it’s a net exporter of fossil fuels, producing much more than it consumes, the true number is far higher: The oil and natural gas extracted in Colorado in 2018 will, once combusted, release over 425 million tons of CO2e into the atmosphere, according to EPA calculations. In other words, methane leaks account for less than 2 percent of the state’s overall carbon emissions.

“When you really look at the climate impacts of oil and gas, methane doesn’t matter,” says Nichols. “I’ll be brutally honest: It absolutely does not matter at all. What matters is the downstream emissions, and the only way to reduce those downstream emissions is to actually limit production and limit the scale of development, which is not something that Hickenlooper has expressed any interest in, or even acknowledged as necessary.”

Since methane leaks are essentially wasted natural gas, drillers have a pre-existing incentive to detect and stop leaks, making their operations more efficient and improving their bottom lines. Colorado’s three largest oil and gas operations happily supported Hickenlooper’s push for new methane rules in 2014, and historically combative industry groups put up little opposition.

In fact, some activists worry that the focus on methane regulations actually helps encourage more fossil-fuel development by fostering a public perception that oil and gas extraction can be done in a climate-friendly way.

“We’re increasingly seeing methane as a complete distraction from real climate solutions,” Nichols says. “It’s almost like it’s playing into the industry’s hands, because at the end of the day, methane rules do incentivize more production. It may be more efficient production, but it’s still more production.”

Hickenlooper, a former petroleum geologist who once bragged about drinking a glass of fracking fluid and was nicknamed “Frackenlooper” by his environmentalist critics during his time as governor, faces an uphill battle in connecting with Democratic voters, for whom polls show climate change is a top priority. He’s one of just four primary candidates to refuse to sign the No Fossil Fuel Money pledge, and on a stage full of rivals pushing far more aggressive measures to combat climate change and reduce fossil fuel use, he could struggle to stand out – first-in-the-nation methane rules or not.

“If you are truly serious about climate, you cannot embrace policies that actually encourage more oil and gas development,” says Nichols. “If you can’t rein in production, then we’re not making any progress.”