Jay Vollmar

Audio By Carbonatix

A little over two centuries ago, much of the land that would become Colorado was claimed by Spain. But since the Mexican-American War ended with the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, moving the territory into the United States, it has never been a requirement for anyone in charge of this place to speak Spanish.

Even so, many of the state’s top elected officials use the language in public – frequently and confidently. Mayor Mike Johnston says that speaking Spanish is “the most useful skill I have.”

“For any leader, whether you’re an elected leader or a business leader, there’s a huge part of your neighbors, your client base, your constituents, who are going to be Spanish speakers,” Johnston says. “It seems like a net advantage to be able to talk to them directly.”

After all, about a third of Denver’s residents, over 200,000 people, identify as Latino, as do nearly a quarter of the state’s population – 1.3 million people. “Colorado” is a Spanish word – it means “colored red” – and place names like Pueblo, Mesa Verde, La Junta, Limon, Buena Vista, Alamosa, Salida, Las Animas, Arvada, Alma and Alameda are all Spanish.

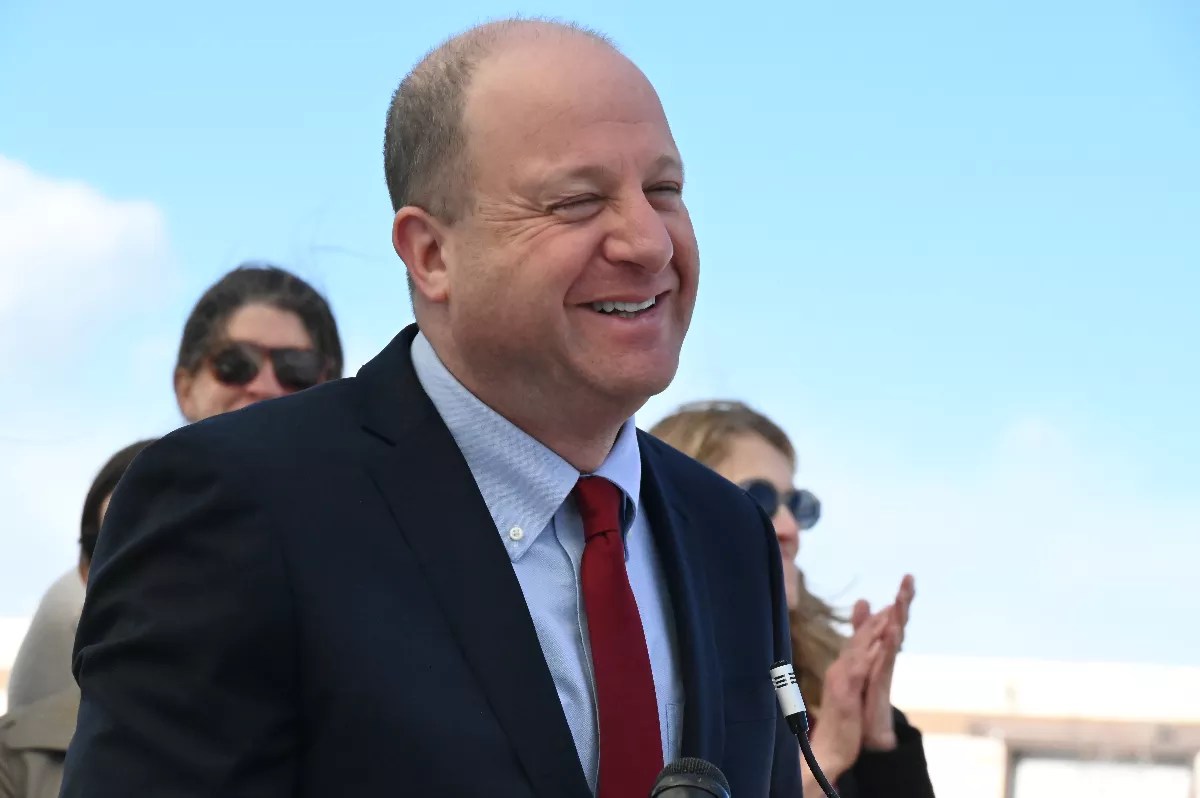

“There are many Coloradans who never even studied Spanish who speak dozens of words in Spanish, sometimes without even realizing it, because it’s entered our Colorado common language,” says Governor Jared Polis. “In Colorado, Spanish is a very widely spoken language.”

Gov. Jared Polis can speak, and sing (sort of), in Spanish.

Bennito L. Kelty

Ken Salazar, who was a U.S. senator from Colorado, served as the Secretary of the Interior and is now the U.S. ambassador to Mexico, comes from the San Luis Valley, where a unique dialect of Spanish is found; he’s part of the fifth generation of a family that settled there in the 1800s. “There are areas of our state where storefronts, businesses are in Spanish predominantly,” Polis says.

Multi-generational Spanish speakers like Salazar are “just a small minority of the Spanish-speaking population of Colorado,” Polis adds. “Most of the Spanish-speaking population are of recent, first- or second-generation Mexican heritage, and now, increasingly, Central and South American heritage.”

Dual-immersion schools, where students are a mix of native English and Spanish speakers who graduate fluent in both languages, are “very popular” across the state, Polis notes, with about 41 such schools teaching kids in grades K-12 across sixteen Colorado school districts. Elementary schools where the majority of the students come in with Spanish as their first language “are not just in places like Denver,” he adds. “They’re everywhere, from Garfield County to Boulder County to Colorado Springs.”

Six of the thirteen members of the current Denver City Council are Latina, including President Jamie Torres. Latinas are in powerful legislative seats, too: Yadira Caraveo is a U.S. representative, and Monica Duran is the Colorado House majority leader.

Not all Latinos speak Spanish, of course. But Colorado’s two U.S. senators, its governor and the mayors of two of the state’s biggest cities all do – even though none of them have Latino roots. “I never really realized it before,” Polis says. “But I guess you’re right.”

Movies and Music in Spanish: How Jared Polis Learned the Language

Polis started learning Spanish in elementary school when he was growing up in Boulder, then continued studying it in high school when he lived in La Jolla, California. He also learned German, which he says he gets to use occasionally.

“Every now and then, I get to positively delight a nice old German lady by whipping out my German,” he says. “I think I win a few votes that way.”

But he’s never stopped practicing Spanish.

In 2003, when he was serving on the Colorado Board of Education, Polis started Cinema Latino, a movie theater company that showed films in Spanish, “so I spoke Spanish in a business setting,” he says. Cinema Latino went bankrupt in 2020, a year after Polis took office as governor. Before that, he’d served five terms as a U.S. representative in Congress; for part of the time, he was chair of the congressional U.S.-Mexico caucus.

“It never got dusty,” he says of his Spanish. “There were always periods of days or weeks where I would speak largely Spanish because of my business work or official work, and even now it comes up regularly.”

Governor Jared Polis sang “Feliz Navidad” as a holiday gift to the world.

YouTube

In a mix of English and Spanish, Polis explains that nowadays, “I can converse in Spanish. I would never say I’m fluent, but I’m conversant, fully conversant in Spanish.”

Sometimes too conversant. Over the holidays, Polis belted out a few lines of “Feliz Navidad” in Spanish for a social media post. The video went viral, and drew sharp criticism as an insensitive move when about 40,000 migrants, mostly from Venezuela, had come to Colorado over the previous year. But Polis weathered the storm.

From Principal to Alcalde: How Mike Johnston Learned the Language

Mike Johnston, who grew up in Vail, started learning Spanish in high school, but credits his time as a school official with making him far more fluent.

“I had learned it throughout my career, but when I really spent the most time at it was when I was a school principal,” Johnston says, referring to his time at Mapleton Expeditionary School of the Arts in Thornton from 2005 to 2009.

“Those were four years of a lot of Spanish practice,” he adds. “The majority of my kids were from immigrant families, from either Mexico or Guatemala.”

Johnston co-founded the school, which teaches college prep and public service to kids grades 7-12, because he was “in part attracted to that community because I spoke some Spanish. I thought it would be helpful in building bridges to the neighborhood, and they took me from novice to conversational,” he recalls.

“I spent a lot of time talking to their parents, talking to students. That was my best practice. I did study it in school, but really, the chance I got to practice it every day was as a school principal.”

Mayor Mike Johnston answers a question in Spanish during a press conference.

Bennito L. Kelty

Johnston left MESA to serve in the Colorado Senate from 2009 to 2017. He was one of the few Spanish speakers in the legislature and, for a time, the only Spanish-speaking state senator, making him the go-to for certain interviews.

“It meant if there was ever any piece of legislation that Spanish-language media wanted to talk about, I was the one they’d go to,” he says. “I got to know a lot of the anchors and a lot of the reporters pretty well.”

When Johnston won his election on June 6, former mayor Federico Peña, who grew up in Brownsville, Texas, came up to him and said, “This is a big deal. This is only the second mayor in Denver history who speaks Spanish after me. And it’s been forty years.”

Not quite. When current U.S. Senator John Hickenlooper became mayor of Denver twenty years before Johnston, he was working on mastering the language.

Geology, Cerveza and Honeymoons: How John Hickenlooper Learned the Language

Both of Colorado’s U.S. senators use Spanish publicly. Michael Bennet has spoken Spanish in radio interviews and attack ads.

Hickenlooper, who grew up in Pennsylvania, says his first experience with Spanish came in 1975, when he was 23 years old and drove to Costa Rica in his $360 Volkswagen Fastback for a ten-month geology work program.

On his way to Costa Rica, he stopped in Cuernavaca, Mexico, and attended one third of a six-week Spanish course. After he left the city and was passing through the Altiplano Mexicano, or elevated plains of Central Mexico, Hickenlooper was stopped by the federales, who noticed a pile of junk covered with a blanket.

“They thought it might be a machine gun or something,” Hickenlooper recalls. “They thought I was a drug dealer originally, then they thought I was a gangster with a machine gun. They cocked their weapons.”

Instead of shooting, though, they lifted the blanket and “they saw it was a banjo” on top, Hickenlooper says. “The captain had a guitar in the pickup truck – they had a Land Cruiser – so we played several Mexican folk songs.”

Laid off from his job as a geologist, in 1988 Hickenlooper co-founded the Wynkoop Brewing Company, Colorado’s first brewpub, and “at that time I was doing restaurants and renovating old buildings and kind of doing redevelopment. A lot of that was tied into the Spanish workforce; a lot of Spanish was being spoken,” Hickenlooper says.

So after he got married, he and then-wife Helen Thorpe went on a honeymoon – he calls it their “luna de miel” – to Oaxaca, where they spent three hours every morning in a Spanish class. He wasn’t thinking that the language would come in handy if he went into politics, he says; he just had a fascination with Latin America, “our best political partner.”

He regrets not studying the language sooner. “I love Spanish,” he says. “I just love it. I never studied [it]. I studied Latin just because the guy who taught Latin loved soccer, and I was a good soccer player. It’s one of my many regrets from high school.”

U.S. Senator John Hickenlooper lets his translator answer a question about migrants in Spanish.

Bennito L. Kelty

Hickenlooper was elected mayor in 2003, left office at the end of his second term to run for governor of Colorado, and after two terms in that office became a U.S. senator. (He also made a presidential bid.) He says his Spanish has “been useful everywhere.”

These days, Hickenlooper travels with a translator to help him out on Senate business, but he’ll still take questions in Spanish – though he usually answers in English.

Mayor of the “World in a City”: How Mike Coffman Learned the Language

The Colorado politician who works the hardest at improving his Spanish is a former congressman and the current mayor of Aurora: Mike Coffman.

“I really force myself,” Coffman says. “If I didn’t speak or study it for a week, I’d be slipping.”

Aurora bills itself as “the world in a city,” and is “certainly the most diverse community in the state,” Coffman says. It’s the third-largest city in Colorado but has the second-largest percentage of Hispanic residents, right behind Denver.

Of the nearly 400,000 residents, about 120,000 identify as Latino. About 86,000 of those people came from Mexico as immigrants, and another 10,000 are from Central America. More than 2,000 Aurora residents arrived here from El Salvador.

Aurora Mayor Mike Coffman listens to residents during a town hall.

Bennito L. Kelty

The first political debate in Spanish between two non-Latino candidates was a decade ago, when the then-incumbent 6th Congressional District U.S. representative (Coffman) debated progressive Andrew Romanoff. The debate was “highly scripted. I knew the questions,” Coffman admits. “We worked out the questions in advance.”

Coffman, who grew up in Aurora, went on to win re-election in 2014; soon after, the district was redrawn to include more of Aurora. To continue reaching his Latino and Spanish-speaking constituents, and anticipating he’d be dealing with more immigration issues, he stepped up his efforts to master the language.

He was criticized, though, for being a Republican trying to reach Hispanic voters by speaking Spanish – especially in 2016, during Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. But he defends the move.

“It was a softening of the image of a Republican in a very diverse community, to be able to say, ‘Oh, okay, he respects us,'” Coffman says. “The more popular view of Republicans is anti-immigrant, but that helped break that narrative.”

In 2017, he started a Twitter account in Spanish, @MiRepCoffmanCO. It lasted more than a year and 268 tweets before it was shut down, shortly after conservative Twitter users blasted Coffman’s support for DACA.

But Coffman takes learning seriously, and he kept studying the language. He hired a retired schoolteacher from Colombia as a Spanish tutor, and has taken classes with her for two hours every Sunday night for the past ten years, he says.

Today he does radio and TV interviews in Spanish. He emails his assistant in Spanish. He hosts town hall meetings in Spanish. He’s considering delivering a State of the City address in Spanish.

In early December, Coffman went to Chihuahua, Mexico, to sign a sister-city agreement; many of Aurora’s Mexican immigrants come from Chihuahua.

“I did everything in Spanish, all the meetings in Spanish. I was pretty fried by the end,” he admits. “It did help my Spanish, but then I was so burned out I took a break and slid back a little.”

Speaking Spanish is “an enormous sign of respect for the Hispanic immigrant community,” Coffman says. “I know when I do news, even if I make a mistake – I make fewer now – that they would rather have me make a mistake than do it in English.”

A Sign of Respect: How Spanish Has Helped With the Migrant Crisis

Polis and Hickenlooper both polish their skills by conversing with native Spanish speakers. While the language comes in handy for politicians, Polis notes that “it’s a great skill for anyone.”

Spanish is “absolutely” helpful for dealing with the migrant crisis, says the governor, who’s met with dozens of Venezuelan migrants.

“Just to hear firsthand from people rather than through intermediaries exactly what’s going on,” he adds. “I was able to hear their stories and what they faced and what they faced going through Mexico, what they faced in Colorado.

“It’s been very helpful in working with Denver and others to craft a successful response.”

Mayor Mike Johnston, pictured with Globeville residents, studied Spanish as a school principal.

Bennito L. Kelty

Denver had already been in a state of emergency for almost eight months because of the influx of new arrivals, as Texas Governor Greg Abbott (another Spanish speaker with no Hispanic roots) continued busing migrants from the southern border to the Mile High City.

While the new mayor knew that his Spanish would be useful in office, “I could not have anticipated the extent to which it would be important firsthand when I’m standing in a group of eighty newcomers from Venezuela who are tightly gathered around me, wanting to have their questions answered,” Johnston says.

His Spanish skills “helped tremendously. It means I can have real, direct, personal conversations with every person who’s arrived, and I think they feel a sense of connection and comfort because I can speak the language,” he adds.

“And there are certain things it’s just hard to do through translation. When someone’s in tears and telling you their story, it’s hard to turn to a translator,” Johnston says. “I get much more direct, much more moving, much more authentic feedback than I would get if I had to go through a translator. That, I think, is a gift in itself, because often it’s not what people say but how they say it, and if you can’t feel the emotion, understand the nuance of the language, it’s harder to hear.”

In his own words, Johnston recites the most common things he hears from migrants:

“Gracias, alcalde, estamos feliz para estar aquí en Denver.” (Thanks, Mayor, we’re happy to be here in Denver.)

“Quiero decirle que no necesitamos nada. Solo que quiero es un trabajo.” (I want to tell you that we don’t need anything. All I want is a job.)

“Me puedes ayudar encontrar un trabajo?” (Can you help me find a job?)

The Vote Is In: Practice Makes Perfect

Hickenlooper vouches for Johnston’s Spanish abilities. The two talked to migrants together in February.

“His Spanish is excellent,” Hickenlooper says. “He’s obviously someone who has taken the time and the effort. Maybe he’s not perfectly fluent yet, but boy, he was very effective at making sure he was understood.”

Johnston is proud to say that his Spanish “has gotten much better” over the years. One of the key improvements, he says, has been learning different accents in Spanish.

“The Venezuelan accent was difficult at first. It’s a very different accent than Mexico or Spain or even Guatemala or Costa Rica,” Johnston says. “There’s always more to learn.”

His other struggles involve the subjunctive, which is used to express desires, opinions and possibilities, among other things. “I’m still not as good as I could be,” he says. “Sometimes I avoid those.” Conjugating verbs mid-sentence is a challenge, too.

Highly technical terms are beyond Johnston’s current skills, he admits. For example, he couldn’t explain in Spanish “what the credible fear standard is for asylum applicants versus temporary protected status recipients,” he says, referring to the guideline for granting legal asylum in the U.S. based on the reason a migrant leaves their country.

“There’s some technical language that I’m less good at,” Johnston says. “But I’ll either use Spanglish sometimes or I will just go to the most common word and not the technical one.”

During a press conference to talk about a new pilot program to decrease car thefts in Denver, the term for “car theft” (el robo de los carros) escaped Johnston while he was answering a question from a Spanish-speaking reporter.

Colorado’s other Spanish-speaking politicians have made similar stumbles. Although Polis can “follow most conversations” in Spanish, “there are technical words that I won’t know how to say,” he says. “So, like, when I’m doing a briefing on something that I normally do in English, I might have to learn the terms for ‘economic growth projections’ or something like that.”

Vocabulary is a problem for Coffman, too. While he has no problem “if I’m speaking about policy, if I were speaking about poetry or something like that, it would probably be a mess,” he admits.

Mike Coffman keeps practicing his Spanish.

Courtesy of Mike Coffman

“Where I have trouble is describing things sometimes,” Coffman says. “You learn the kind of vocabulary for what you’re working at, so it’s easier for me to talk about things related to politics in Aurora.”

But he keeps practicing.

“I usually don’t watch much in the way of TV, but when I do, it’s in Spanish,” Coffman says. “Most of the TV I watch is in Spanish. I watch the news in Spanish, new shows in Spanish. Sundays, I love travel shows; there’s a travel show in Spanish that’s really good.”

Because he watches local TV news in Spanish, he’s seen Polis speak Spanish, and “I’m impressed by him,” Coffman says. “I’ve seen Mike Johnston on Spanish news programs, and I think he’s pretty good.”

Sometimes Coffman even sees himself speaking Spanish on the news. “I think, ‘Oh, my God, you can do better than that,'” he says.

Johnston’s twelve-year-old daughter turned him on to Duolingo, the popular language-learning app, and he practices with her and his two boys, who are also trying to learn Spanish.

“But my best way to practice is with people,” Johnston says. “At this age for me, the best way is live conversation with native speakers who can help me find the best words and the best phrases.”

Jose Salas, a spokesperson for the mayor’s office, helps Johnston with idioms that might not make sense with a simple translation from English to Spanish. “I practice a lot with him on ‘I think this is how I’m going to say this’ but it’s not the right way,” Johnston says.

“He’s pretty good,” Salas says, adding that “it’s usually just like one word” that might need fixing.

Johnston says he’s trying “to make sure not to make the most classic Spanish mistake for a novice, saying ‘Estoy embarazada’ when you think you’re saying ‘I’m embarrassed’ but you’re saying ‘I’m pregnant.’ You try to avoid those.”

Once while talking to Spanish-language media off-camera, Coffman made a more embarrassing version of that classic mistake: He mixed up the word for pride (“orgullo”) with the word for orgy (“orgía”).

“They all just sort of stopped,” he says. “Then, in their kindness, they all started laughing.”

Westword staff writer Bennito L. Kelty grew up in a bilingual household in Aurora, with an Irish-American dad and a Mexican mom (his father was actually his mother’s English teacher when they were in their twenties).

“I didn’t take studying it seriously until I worked at the border,” Kelty says. “I worked in Southern Arizona for more than three years and interviewed Spanish speakers on both sides of the border, including migrants. I also wrote stories in Spanish and translated others. I won a first-place Arizona Press Association award in 2021 for best Spanish-language community reporting.

“All of my mom’s family is in Mexico, and I visit the country every year,” he adds. “That trip is always a boost to my Spanish, and it would start to slip if it weren’t for the way Denver has been impacted by the migrant crisis. Just about every week, I’m writing about the stories of Venezuelan migrants I interview in their own language. ”