Bennito L. Kelty

Audio By Carbonatix

Despite support from the public and elected officials, the Denver Basic Income Project will halt its experiment of giving low-income and homeless residents free monthly cash payments for the upcoming year after Mayor Mike Johnston left the program out of the upcoming city budget.

But founder Mark Donovan isn’t ready to end it all just yet.

“There are a lot of people who want to see this work continue,” Donovan says. “We started last year with zero dollars in the budget, so it doesn’t mean we’ll end.”

Donovan is adamant that DBIP still has a long future, and says he’s far from quitting. While the organization looks to secure new funding, he plans to use the hiatus to work on organizing and sharing data he’s collected alongside research partners at the University of Denver.

Donovan started out by handing out $1,000 grants to Denver residents impacted by COVID-19 in 2020. In 2021, he started working on the pilot phases of the Denver Basic Income Project, supported by $500,000 he made from early investments in Tesla. Unlike universal basic income, which would give cash to everyone, Donovan designed DBIP to focus specifically on the homeless community.

After two pilot phases, Denver City Council approved a $2 million contract in the fall of 2022 to help fund the Denver Basic Income Project for a full year of regular cash payments. With only three full-time employees, including Donovan at the helm, DBIP launched that fall with more than 800 recipients recruited through referrals by homeless and social services organizations. Donovan says it was the first major effort to test out the idea of a basic income in the United States.

The project was structured like a research experiment, with the University of Denver’s Center for Housing and Homelessness Research helping plan how to hand out the money. The participants were split into three different groups: one receiving $1,000 a month, another receiving $6,500 in one month and $500 a month afterward, and a comparison group that received only $50 a month.

In July, DBIP released the results of its first full year and found that more than 300 of its participants, more than 45 percent, had moved off of the streets and into rented or owned housing after ten months. The results also found a small disparity between the different groups that suggested the amount given didn’t matter as much. Donovan interpreted the results to mean that what people really need is compassion and respect.

“The gap was smaller than people expected, and that’s something we want to understand better,” he says. “We think it raises the importance of the way we work with people and the way we express trust and back that up by giving the cash unconditionally.”

But Mayor Johnston interpreted the data differently, according to his staff.

“Unfortunately, the data in the year-one report from the DBIP did not show a statistically significant difference in homelessness resolution between the groups that received large cash transfers and those who did not,” Jordan Fuja, a spokesperson for the mayor’s office, says in a statement. “Because the data showed limited results in the first year, [the Department of Housing Stability’s] proposed budget does not recommend funding in 2025 for this program.”

On September 12, Johnston revealed his proposed 2025 budget for Denver. The $1.76 billion budget was just 0.6 percent larger than last year’s, which is the smallest annual budget increase since 2011, aside from the 2021 budget that came after the pandemic.

Stunted by a slowdown in local sales tax revenue, Johnston’s proposed 2025 budget cuts of $86 million in yearly funding from All In Mile High, his homelessness initiative, and $90 million from Denver’s migrant response budget. The mayor’s office plans on “using [the Denver Department of Housing Stability’s] limited dollars for programs that efficiently help as many people as possible get and stay housed,” according to Fuja.

And that means cutting funding for DBIP, too.

“We are always interested in trying new innovative strategies to solve our toughest challenges,” Fuja says, “which is why we provided funding for the Denver Basic Income Project’s pilot program.”

DBIP has received $4 million in funding from the City of Denver, with two contracts for $2 million in 2022 and 2023. However, one of those contracts was approved by former Mayor Michael Hancock’s administration.

Along with funding from other partners, the project has raised around $14 million and given out about $10.5 million in direct cash payments to 850 people since 2021, according to Donovan.

DBIP still has “very strong and loyal” partnerships, according to Donovan, with current private funders including the Colorado Trust, the Piton Foundation, the Denver Foundation, Rose Community Foundation and Gary Community Ventures, which Johnston used to run, among others. The organization also continues to work with public funding from the Colorado Department of Local Affairs and brings in individual donations.

“We’ll move this forward,” he promises. “We’ll continue to move this forward with whatever funding we’ve got.”

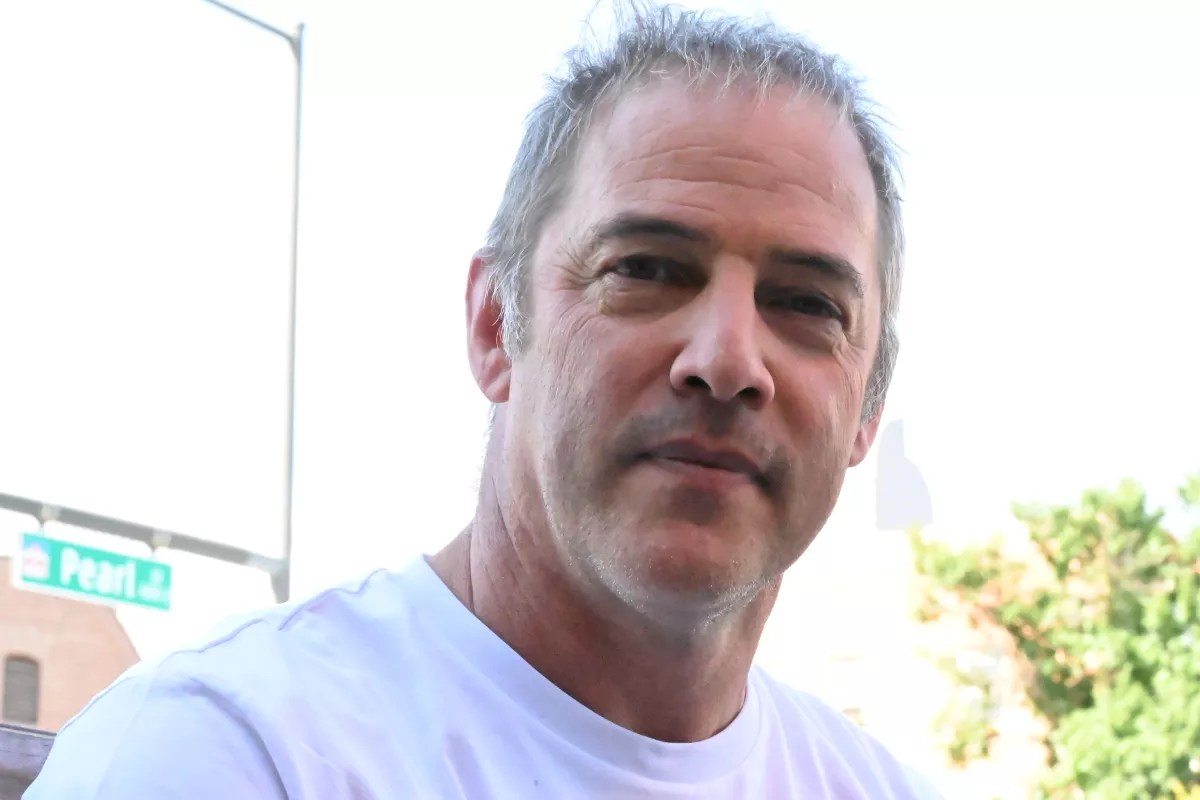

Denver Basic Income Project founder Mark Donovan spoke to dozens of supporters of his efforts during a rally at the State Capitol in 2023.

Bennito L. Kelty

Donovan says it was “a surprise” to learn he’d be losing city funding, however. He says that he hasn’t had the chance to sit down and talk with Johnston and use the year-one data to convince the mayor that DBIP is a cost-efficient solution to homelessness.

“I understand it’s a tough budget year with limited resources,” Donovan says. “We’re happy to sit down and compare our outcomes and the cost to reach those outcomes with the city. We think we’re a highly efficient solution.”

The project was once supported by Johnston, who previously said it had a “vital role” in solving homelessness. DBIP was also endorsed by four current Denver city councilmembers, and dozens of supporters rallied outside the State Capitol this year and last for the continued funding of DBIP.

“We believe that the money that we infused into this community contributed to the House1000 results and is contributing to the All In Mile High goals that the mayor has set,” Donovan says. “It’s best to go together. If we work together with the mayor’s office, with the city, we’ll be able to move faster and have a greater impact. But like I said, we’ll continue to do the work because we believe in it so deeply.”

Until DBIP gets more funding commitments, Donovan says it will have to stop its flagship service of providing an income floor, but it won’t stop its secondary function of providing data-driven insight into direct cash and its impact on those experiencing homelessness

While Donovan looks for new funding sources, he’s going to work on making the data collected from DBIP’s first year more accessible. He wants to sort out the data he has so far – including feedback from participants and statistics on how many attain housing or jobs, among other information – and publish it online to be used as open-source data to be shared without restrictions. Donovan wants “more researchers and more eyes on that data to learn from it,” he says.

“We’ve had a lot of inquiries and interests from around the country,” Donovan says. “This being the first and largest to do this at-scale for this community, it’s really important to the [basic income] movement.”

Based on monthly survey responses from participants, DBIP estimates it saved the city $590,000 in the use of taxpayer-funded public services when the stipends were handed out from late 2022 to early 2024. More than a dozen participants reported finding full-time jobs during the first year, according to DBIP, while the percentage of participants who said they could pay their bills on time went from 29 percent to 50 percent.

That data can only offer so much, though, warns Donovan. A one-year experiment is a small sample size for a big idea like free monthly income.

“This is just a complex challenge, and there are different demographics within the unhoused community. I think there may be different approaches for different parts of the community. This is something that, the longer we look at this, we keep learning,” he says. “But we’re not going to understand it better if we don’t keep running the program.”