Getty Images

Audio By Carbonatix

With the summer sun shining bright on a recent Tuesday morning, three retirees and a man less than half their age teed off at Wellshire Golf Course in south Denver for half a round of golf to start their day. In the two hours that followed, each of the four players hit some great shots, while also executing the occasional dud or slicing onto the next hole. But for the most part, even the poor shots didn’t feel too painful, since the open fairways were generally friendly to golfers who had come out more to have fun than to keep a close eye on their scores.

As a bonus, the two hours of enjoyment in the great outdoors only cost the young man $29 and the three retirees $24 each – very reasonable prices for summer golf.

That bang for your buck is representative of all of Denver’s municipal golf courses, which have scored with residents and visitors alike for over a century.

Denver residents have been playing at city courses for over a century.

Denver Public Library

At the end of the nineteenth century, private clubs with golf courses started popping up around Denver. They catered to the nouveau riche, many of whom had made their fortunes in the mountains. But while these courses were accessible to those with means, less wealthy Denver residents couldn’t afford to join – and Catholic, Jewish, Latino and African-American residents often weren’t allowed to.

Municipal courses addressed that inequity.

The City of Denver got into the golf industry at the beginning of the twentieth century.

In 1909, the city struck a deal with the Interlachen Golf Club to build a nine-hole golf course in the Berkeley neighborhood in northwest Denver. The city handled the maintenance of the course, and its residents were able to golf at the club during the week. The members of Interlachen had the course to themselves on the weekends. “That was the first public golf that Denverites could play,” says Rob Mohr, who, along with daughter Leslie, wrote the book on the sport in the city: 2011’s Golf in Denver.

In 1911, Denver City Council passed a resolution allowing the city to build its own municipal golf course.

Construction on City Park Golf Course began in 1912, and the course opened to the public in 1913.

Back then, City Park Golf Course was “pretty straightforward,” says Mohr, who’d just left a metro Denver course to take an interview call. City Park had nine holes and sand greens, and didn’t even have grass tee boxes. But it was definitely accessible to the public. In fact, during its first few years, City Park charged no greens fees, and Denver residents of all races, religions and incomes could just walk onto the course and play for free.

Over its first five years of operation, the course added grass greens, grass fairways and a clubhouse.

Unfortunately for golfers, it also started charging money.

Denver’s next foray into municipal golf was outside the city. In 1919, Denver had bought land in Evergreen for the construction of a dam on Bear Creek in order to build a reservoir. Six years later, it added a nine-hole golf course, now known as Evergreen Golf Course; it opened in 1926.

In 1929, Denver built a nine-hole course called Berkeley Park Golf Course. Five years later, it purchased an adjacent course and combined the two to create Willis Case Golf Course. The name was an homage to Willis Case Jr., a wealthy stockbroker who’d been killed by his girlfriend in a murder-suicide. Case had left an endowment to the city to build a golf course.

Soon after, Denver built a nine-hole course at Overland Park in south Denver, which had previously held a private course belonging to posh Overland Country Club, founded in 1896. By 1908, however, all of that club’s members had left to form a new club in Lakewood.

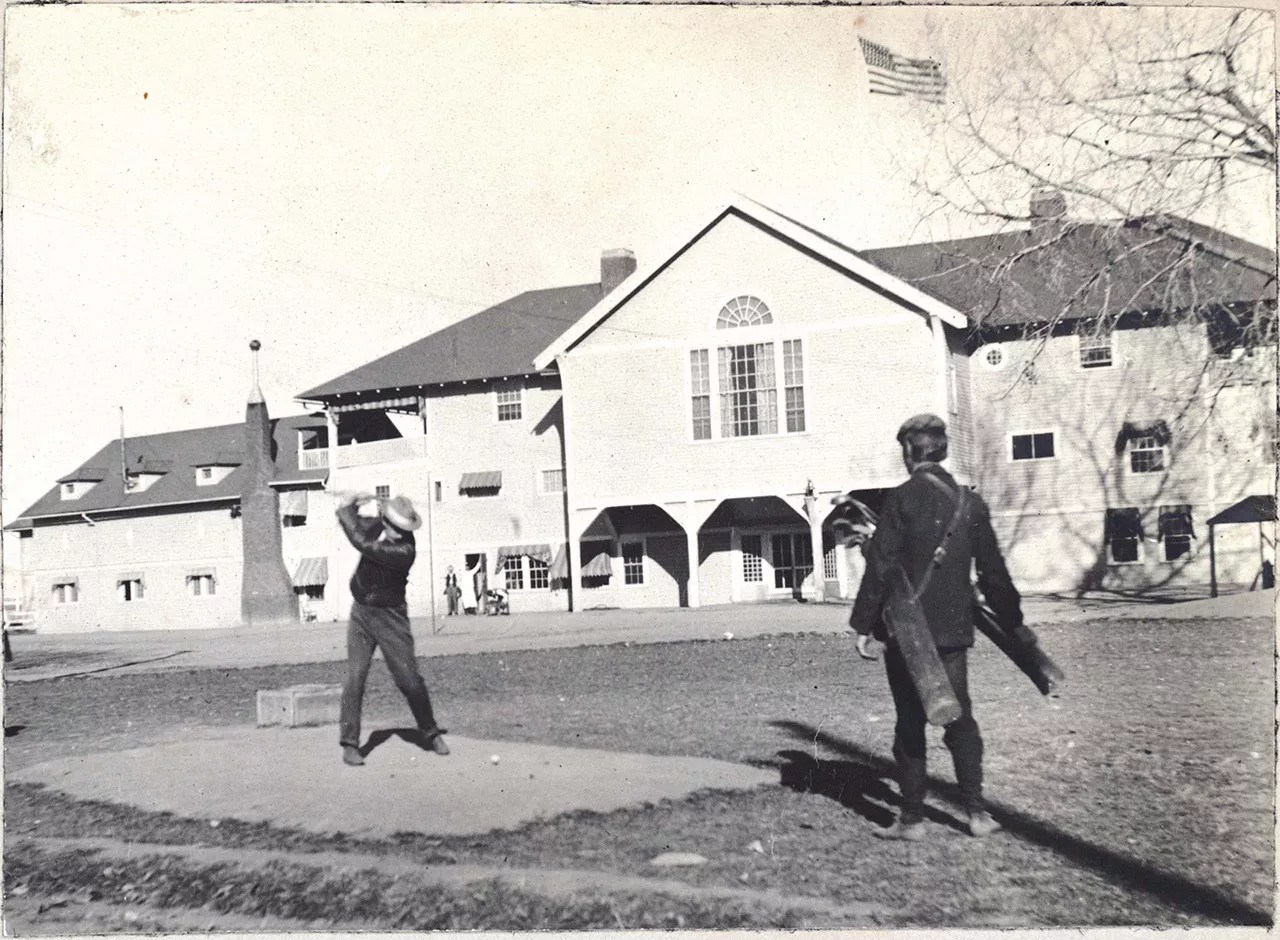

A golfer teeing off at Overland Country Club, the future site of Overland Park Golf Course.

Denver Public Library

“The Overland course was abandoned at that time, and the Overland property was used for various purposes, including an agricultural exhibition, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, an early airplane flight and crash resulting in death, and automobile racing,” Mohr says. “The property was purchased by the City of Denver in 1919.”

In 1932, Denver built a new course there, on top of the remains of the private course. Since little of the original remains, Overland’s claim to being the oldest operating course west of the Mississippi ought to come with a big asterisk next to it.

The city wasn’t yet done spending money on golf during the Depression years.

In 1936, the city purchased a private club that had gone into bankruptcy, complete with a course designed in 1925 and 1926 by renowned golf course architect Donald Ross. Known today as Wellshire Golf Course, it’s Ross’s only municipal course west of the Mississippi.

But all of Denver’s courses have specific things in common. “There’s a certain charm that they all have,” says Ed Mate, who grew up in Denver and today is the executive director of the Colorado Golf Association. “They didn’t have heavy earth-moving equipment when those courses were built.”

As a result, the courses all had small greens that were simply built on a particular patch with earth that was piled up and shaped. The greens seem natural, especially when compared to newer courses that feel “manufactured,” according to Mate.

The layout of Denver’s municipal courses also show a certain amount of consideration for the game itself, since they weren’t built by real estate developers who wanted to maximize profit rather than athletic challenges. “I always say that routing is to a golf course what a plot is to a good book,” says Mate, a big fan of how Denver’s courses are routed. When Ross designed a course, for example, he cared most about how the course played and had no motive to fit as many holes into as little space as possible.

Kennedy Golf Course, added in the ’60s.

Denver Golf

In the 1960s, Denver added Kennedy Golf Course, an eighteen-holer in growing southeast Denver. The city also built Aqua Golf, a family-friendly facility with a miniature golf course as well as a driving range with mats set in front of a lake into which players can tee off.

Harvard Gulch was added in 1982.

Denver’s golf courses putted along for decades as fancy new courses appeared all around in the suburbs.

The peak of golf course development in this country came in the 1990s and 2000s, during what Richard Singer of the National Golf Foundation refers to as the “Tiger Boom.” With a young Tiger Woods absolutely riveting crowds with his dominance and passion for the game, more and more people wanted to get out on the course. Developers responded by building even more courses.

But that bubble eventually burst, and the golf industry began to suffer from oversupply, then overhype as Tiger Woods fell out of favor.

Then came the Great Recession, and golf courses both public and private began closing in record numbers. Many cities decided that the benefits of municipal courses no longer outweighed the cost.

“Golf is more than just an activity. It’s a lifestyle.”

“In a lot of cases, with cities, it can solve a lot of their economic problems if they were to let it go,” says Singer.

Often, while a city could cover day-to-day costs, a course didn’t make enough to fund major capital improvements, so either the course fell into disrepair or the golf program went way over budget.

Selling a course to a developer looked pretty attractive to some cities. “I think a lot of municipalities, if they were to give up golf, the properties that the golf courses sit on would end up getting gobbled up by developers,” Singer says.

Denver managed to hang on to all of its municipal courses through those tough times.

The courses are assets for more than golfers. They also create large swaths of open space in a place like rapidly developing Denver. While non-golfers can’t simply walk onto a course and picnic, just walking or driving past one can provide a feeling of serenity.

And then, of course, the sport still has plenty of fans. “It has a large well of very dedicated participants who won’t give it up for anything,” says Singer. “It’s a very important part of their life. Golf is more than just an activity. It’s a lifestyle.”

Compared to the courses built during the bubble years, Denver’s municipal courses stand out for their historic vibes.

“They have a classic country-club feel to them, where they have parallel fairways and it’s super-hard to lose a ball,” notes Craig Lemley, co-founder of the online Colorado Golf Blog. “When you’re at Wellshire or Overland, these courses that have been around for decades, it’s like that rich mahogany kind of vibe when you walk in there. You feel like you’re walking through old cigar smoke.”

A City Amateur Senior Women’s Tournament at Overland.

Tanner Gibas

Today, golf in Colorado is a $2 billion-a-year industry, according to a National Golf Foundation analysis. And the state’s municipal courses tend to do pretty well, Singer says.

The City of Denver owns eight golf facilities: Wellshire, Willis Case, Overland Park, City Park, Evergreen, Kennedy, Harvard Gulch and Aqua Golf. While the first four are regulation eighteen-hole courses, Evergreen is an “executive course” – terminology used to describe an eighteen-hole course that is significantly shorter than regulation courses. Kennedy has three separate nine-hole circuits plus a par-3 course, while Harvard Gulch comprises a single par-3 course. Add in Aqua Golf, which got an almost $2 million facelift in 2008, and the city’s lineup has something for every level of golfer.

“The city planners, what they did with the Denver golf courses, was just genius in my mind,” says Tom Woodard, the director of Denver Golf from 1996 to 2006. “They took their time, and they put a public golf course in every quadrant of the city.”

But when Woodard took over the program, which is under the Denver Department of Parks and Recreation, it had been financially mismanaged for years and was a million dollars in the hole, he recalls.

Woodard got rid of many of the concessionaires with which the city had contracted to run various operations at the golf courses, and moved those tasks to city employees.

“It was mismanaged,” agrees Scott Rethlake, who took over as the director of Denver Golf in 2006. “They didn’t have a golf pro running the golf divisions.”

Evergreen Golf Course is Denver’s prized mountain course.

Courtesy of Denver Parks and Recreation

Today the city’s various golf facilities are run through the Golf Enterprise Fund. An enterprise fund is a superior model for running municipal courses, according to Rethlake; it’s sustained by revenues derived from the golf operations and is largely financially independent from the city’s general fund.

“Now we’re basically run like a private business, except that if we do have what we call surplus revenue, that money goes back into the golf course instead of into an owner’s pocket,” Rethlake explains. He notes that every year he’s been running Denver Golf, the fund has had money left over that’s been put back into the courses.

In 2019, for example, Denver Golf pulled in $12.997 million in revenue and spent $12.768 million on its operations, resulting in a $229,000 operating surplus. After paying off some bond fees and taking into account capital depreciation and a few projects contracted out to other city agencies, Denver Golf finished the year with just under $24,000 in retained earnings.

Any money put back into the courses pays off. “The conditions are great,” says Lemley.

Denver officials pitch the city’s golf offerings as “your neighborhood golf course,” since there’s a golf course in each section of the city.

“We’re not a country club,” notes Rethlake, who points out that the city courses remain open and welcoming.

“For the price that you pay, what you get is a really good value.”

“Our biggest selling point is value: For the price that you pay, what you get is a really good value,” he adds.

Mate has a special affinity for municipal courses. “Without community golf, I would not be a golfer; it’s that simple. It was the only way that I could afford to play,” he says. “You can keep every country club. You can keep all of ’em. For my money, there’s no place I’d rather play than the local muni.”

Lemley agrees on the good value of Denver’s municipal courses. “They’re meant to be a community asset, so it has to be accessible by all members of the community,” he explains. “That’s why at munis you’ll find a lot cheaper rates to play. You’ll also find a lot more options for the kind of golf that you’re looking for, especially for Denver.”

The city, which adjusts its rates every few years and is in the process of raising them now, tries to stay on the lower end for municipal golf courses.

Besides value, the municipal courses have another major perk: They give newcomers a chance to learn the game of golf without the intimidating frills and pressure of a private course.

“The club I’m a member at, you have to wear your collared shirt. There are rules, basically like an HOA,” Lemley says of the course he plays in Monument. “But then when you go to a muni, it’s an everyman’s game. You can wear a tank top and cutoff jean shorts just to play golf.”

City Park Golf Course is set to reopen in September.

Tanner Gibas

While all of Denver’s municipal courses share value, history and a certain design sense, each has its own charms. But the crown jewel, according to Lemley, is City Park Golf Course.

“It’s branded to be Denver’s municipal course. Their logo has got the skyline. It’s right next to the zoo. It’s one of the oldest, most well-known neighborhoods in Denver,” he says. The view of downtown Denver from the course is spectacular, and golfers feel an immense urban presence while surrounded by greenery. When the course is open, that is.

City Park Golf Course has been closed since the fall of 2017, while Denver has done flood mitigation to protect not just the course, but surrounding neighborhoods.

“The golf course was built originally on a low spot in the area,” explains Rethlake. “The city has grown up around it. That has actually become the largest floodplain, area-wise, within the city. There’s quite a bit of flooding to the north of the golf course, and the south as well.”

The project called for moving the clubhouse. And moving the clubhouse would have required also moving around some of the holes. So the city decided to completely redo the entire course.

“They built a championship golf course,” points out Woodard, “and that’s very unique – to have a golf course like that in the middle of a metropolitan area when so many of them are going bankrupt and they’re not funded well.”

After months of delays, the golf course is scheduled to open on September 1, for minimal play without carts. And then in May or June 2021, it will begin booking a full card of tee times.

“I’m so thrilled that’s still going to be a golf course,” says Mate, who as a kid would bike from his house in Park Hill over to City Park to play.

Wellshire Golf Course comes with a pedigree.

Denver Golf

Making sure municipal golf courses are accessible to kids is a growing concern. Although municipal courses offer a cheaper option, they’re not cheap enough for everyone. And despite the fact that one of the greatest golfers of all time is black and Asian-American, there’s still a dearth of diversity in the professional field.

To ensure that the game attracts more young players of color, the city has a chapter of the First Tee program, which introduces kids to the game of golf and the values that come with it. Denver’s First Tee program is the second-largest in the nation, working with over twenty schools and more than 10,000 children annually.

“It’s really a child-development program that is centered around golf,” explains Rethlake. “It’s not just golf instruction. It’s about learning core values and life lessons. Everything from shaking hands and making eye contact [to] applying for a job and filling out a résumé.” Denver’s First Tee numbers skew heavily toward the female and have diverse ethnic representation, he notes.

Even during the pandemic, First Tee is still operating, albeit with fewer children per class and mandatory face coverings and physical distancing on the course.

“It’s not just golf instruction. It’s about learning core values and life lessons.”

“It has been well received and is going well,” Rethlake says of First Tee’s offerings in the age of COVID-19.

Then again, golf in general is doing as well as any recreational activity during the coronavirus pandemic. It’s a sport with built-in social distancing, which Denver recognized when it reopened courses in late April, with strict safety guidelines.

Golf numbers are returning to a time in the mid-1980s, before the golf course development boom, when every tee time was sold, according to Mate. “People can’t go to a Rockies game, can’t go out to eat, can’t go out to the movies. People are working from home. They now are controlling their calendar more than they used to,” he says.

And they’re grabbing just about every tee time available in Denver.

Denver Golf expects to see a 10 percent increase in rounds played in 2020 compared to last year, says Rethlake, who quickly notes that revenue will be either flat or down by about 10 percent. That’s not because of a lack of players, but because of a 50 percent drop in demand for carts. “There are fewer people riding, and those who do ride are choosing to ride one person to a cart,” he says. “This means less revenue from cart rentals.”

The city is also anticipating a drop in revenue from the sales of merchandise, such as golf clubs, hats and balls sold in the pro shops at each course. Rethlake thinks that could be down 60 percent, while driving-range revenue will likely be down 30 percent, and food and beverage revenue down 35 percent.

That matches the trend that Singer is seeing across the country. “Golf courses rely on those ancillaries to really help them over the hump,” he says.

But Denver’s courses have been in the rough before. And for over a century, they’ve always come out swinging.