Brandon Johnson

Audio By Carbonatix

For the past five years, Gabriel Gravagno has hosted Jazz Jam at the Mercury Cafe every Friday. Before that, he was a Merc employee for several years.

Through it all, Gravagno has seen the venue evolve from founder Marilyn Megenity’s creation into what it is today: a space that’s officially the Merc but hasn’t been the same since new owners took over in 2021.

Entrepreneur Danny Newman, his wife, Christy Kruzick, and business partner Austin Gayer purchased the building at 2199 California Street from Megenity, with the promise of keeping the Mercury alive.

“The thing I was worried the most about when Danny took over was that it would stop being the Mercury,” Gravagno says. “He has kept it the Mercury Cafe…but it is sort of like a husk of the Mercury without the heart of it. … Danny is not Marilyn.”

Gravagno doesn’t blame Newman for not being Megenity, who nurtured the Mercury with everything she had in the almost fifty years she owned the business, from its start as the hippie cafe Elrond’s in Indian Hills in 1975 through its various reincarnations and moves around Denver to its current home, which Megenity bought for $157,000 in 1990. After all that hard work, everyone agrees she’d earned a comfortable retirement. But losing her spirit hasn’t been easy, and it’s taken the heart out of the Mercury.

Over the decades, people got married at the Merc and were memorialized there, shared their poetry or music for the first time publicly on its stage, held revolutionary events full of free thinkers, learned to swing dance on its dance floor, or simply stopped in for nourishment for the body from Megenity’s organic-focused kitchen and for the soul from the others they’d meet at the Merc.

“It’s a second home to me, as it was for many hundreds and possibly thousands of people over the last forty years,” says Julia Fordyce, who worked at the Mercury from 2013 to 2020 and met her husband there. “I lived in four states and about 22 houses by the time I was eighteen, so the fact that I was at the Mercury for eight years and found it to be a sustainable and solid fixture and family was part of what kept me there a long time.”

Fordyce is a painter, and she got to use those skills at the Merc, painting tables and the upstairs area. And she’s far from the only person who’s contributed their art to the space.

“It’s a dynamic, interdependent and sustainable organism that promotes nourishment in food, art, community and culture,” Fordyce says. “It transported you into a different space that was about real, tangible goods and how to survive as a society through food and community and talking to strangers.”

Because a wedding and a metal show and an open mic could all be going on at the same time in various event spaces, there were always people from different walks of life at the Merc. Not everyone always “got” the Mercury, but most left with the realization that this place was unlike any other.

“A lot of people found themselves in there and were like, ‘This is weird. Why is it cash-only? And why is this the driest burger I’ve ever eaten?'” Fordyce recalls, quickly adding that she never felt that way about the burgers. “Yet they would find themselves more often than not connecting directly with people that had different views or perspectives or interests.”

Riley Anne Martin, who worked intermittently at the Mercury between 2017 and 2021, considers the place magical.

“The Mercury, to me, is divine communication between all living beings, invisible and visible,” Martin says. “It feels kind of like a fairy tale, or it used to feel like a fairy tale. Now it feels kind of real and like part of modernity – but before, it felt timeless.”

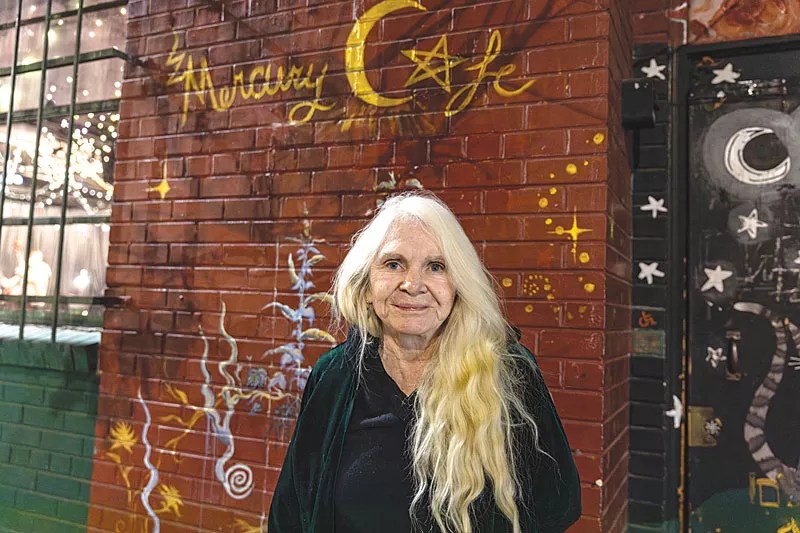

Marilyn Megenity would love to see employees own the Merc.

Brandon Johnson

As Marilyn Megenity sees it, the Mercury was “a spectacular tool for cultural revolution.” From its start five decades ago, she considered the purpose of her cafe/venue as a gathering place for building urban community, and she’s proud and grateful for those who aligned with that mission.

But by 2021, a year into the pandemic, Megenity was ready to retire, so she began looking for a buyer to purchase the business and building. That buyer ended up being the team of Newman, Kruzick and Gayer.

Newman has many memories of the Merc over the years, starting from when his friends at the Denver School of the Arts had a jazz band that played there. He enjoyed the intergenerational contact that came in the all-ages space, as well as the interesting artists he saw there, including Alanis Morissette and Blink-182 before they blew up.

Those memories, coupled with the successful transfer of a cultural icon when he organized his family’s purchase of My Brother’s Bar from the Karagas family in 2017, helped persuade Newman that he could save the Mercury, too.

“It’s something we had the means to do at the time, and we just wanted to make sure that we saved a special place like this for Denver and generations to come,” Newman says. “That was kind of the impetus for everything.”

Megenity sold the business and building to Newman’s team for $2.07 million, signing the deal at the most propitious time according to the stars, as befit her lifelong interest in astrology. Martin, who worked there at the time, recalls that she and other members of the staff were upset that Megenity would be departing – but they agreed that Newman was the best choice for a buyer, once they realized that converting the Merc to an employee-owned model would be tricky and likely wouldn’t provide Megenity with the funds she needed to retire peacefully.

Reflecting now, Martin says she feels the staff and community were lured by Newman’s promise of continuing the Mercury’s legacy, a vision that never materialized.

“We were all really hopeful that it would go into some good hands in that transition,” says Melissa Ivey, a musician and event promoter who had been booking at the Merc since 2001. “We all knew it would be different and things would change, but I didn’t think that we were prepared as a community and as artists to have to ignore these business practices that are not normal and are not sustainable and are not the original intent.”

The Jazz Jam is a Friday fixture at the Merc.

Brandon Johnson

The current business practices weren’t Newman’s original intent, either, he says. Although he had dreams of adding punk back into the Mercury’s lineup, he intended to keep the place mostly as it was – but circumstances in his life kept Newman from handling the business the way he’d planned.

About three months after they purchased the Merc, he and Kruzick found out they were going to have a baby – something they’d been wanting for years and had been told wouldn’t be possible. The energy they’d planned to put into the Mercury was then divided between the business and their baby, creating a smaller role for Kruzick than originally expected.

“How we thought we were going to be operating had to get changed a little bit, but the overall driving principle of keeping this place as similar as it could be, just keeping it going, that was the big plan and big mission,” Newman says.

Earlier this year, family matters struck again, this time horrifyingly rather than joyfully. Kruzick had an “unexpected major health issue,” Newman says, and life was scary and unknowable for a time. Though Kruzick’s health is more stable now, he notes that the months of uncertainty took a toll on every part of their family’s life, including the Mercury.

And the place wasn’t hopping, anyway, even though the new owners had anticipated that people would return to the Mercury in droves once the pandemic eased up.

“It’s going to be the Roaring Twenties again, and it’s just going to be crazy,” Newman remembers thinking. “That hasn’t happened. … I was expecting a lot of groups coming in, because this place is home to so many different groups. … I was thinking that we were just going to get bombarded with ‘Let’s do more of these things.’ It really was the case that people just wanted everything to be exactly as it was.”

And for the first six months, things were largely the same…though the new owners did make some changes. They added a coffee bar designed to fit with the Mercury’s existing aesthetic. They moved the sound booth in the upstairs gathering space and elevated the back area to line up with the height of the bar. They invested in sound and light updates.

Megenity worked closely with the new owners for a time, showing them the ropes. But it quickly became clear “we couldn’t only follow the Marilyn playbook, even if that was our initial intention,” Newman says. For example, when his team took over, everyone was still paid in cash and no one clocked in or out, which had to be changed in order to be in compliance with payroll and labor laws.

“She got away with stuff that we would never be able to,” Newman adds. “Not in a sneaky way. She just did stuff in a way that if I would have come in here and said, ‘We’re doing that exactly the same way,’ any new employees would be like, ‘You’re an insane person.’ But when Marilyn is describing it, it makes perfect sense.”

Newman thinks Megenity must have regularly pulled twenty-hour days doing the hiring, firing, payments, booking and everything else herself, and that no other person could do all she did at the level she did. She’s superhuman in that way, Newman says.

While some workers were okay with the changes, others weren’t. Martin says that she and Newman eventually got in a yelling fight that ended her time at the Mercury.

By then, the Mercury was taking credit cards for the first time in forty years.

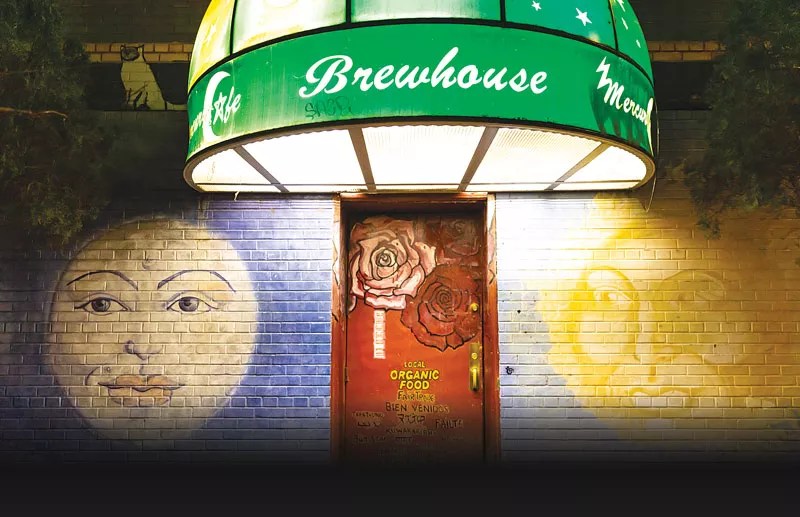

The Mercury Cafe has multiple spaces for dining, dancing and other events.

Brandon Johnson

The pandemic restrictions were gone, but people weren’t coming to the Mercury. In fact, it seemed that fewer and fewer regulars were returning.

Ivey hosted a BIPOC open-mic night at the Merc through Bodies of Change, a nonprofit on whose board she sits. “When the BIPOC Open Stage started about two years ago, there would be someone playing music in the corner, a piano player, a cellist,” she recalls. “There’d be people having dinner already or having coffee, and I remember it was just slowly, slowly, slowly, where it was less and less and less people.”

Food had long been a draw at the Mercury. Megenity always served dishes made exclusively of local, organic ingredients and offered some menu items that were accessible price-wise to the starving-artist types who would often find themselves at the Mercury. Her focus on sustainability was so strong that she retrofitted her car to run on old cooking oil.

Newman credits Megenity for helping jump-start the health-food movement that still exists in Denver today at places like Watercourse Foods and City, O’ City. But food trends have changed since 1975, he says.

“She ran with a very, very interesting menu, very focused on those kinds of things for a really long time,” Newman notes. “Some of the previous thinking around food had started to change a little bit, around ‘There are healthy fats’ and that kind of stuff.”

After a year of maintaining Megenity’s exact menu, Newman’s team realized they needed to tweak some things because food costs had risen 40 percent during that time. “Our food cost was more than what we were charging on the menu, not even to take into account the kitchen, the labor,” Newman says.

So they brought in a friend to consult on modernizing the menu through the lens of healthy, good food that was as “organic and local as possible.” They kept the brunch menu and changed up some other aspects of the food service. That went well, Newman says, until the Merc’s longtime head chef, Jeff Massingill, retired in July 2023. At that point, none of the employees wanted to take over the kitchen, and outside chefs told Newman they weren’t interested in the Merc, either, if they couldn’t have control over the menu.

Hanging at the Merc on a recent night.

Brandon Johnson

For a time the kitchen became non-existent as Newman and his partners issued a call for up-and-coming chefs to use the Mercury’s space. Gringos Tacos moved in for a time, but it became so successful that it moved out and today is part of several Denver venues and arenas. Now, Uptown & Humboldt runs a food service at the Merc.

“Pre-COVID, this place was a restaurant and bar as well as a venue, so it was always just packed full of people coming here just for the food and just for the atmosphere,” Newman says. “Post-COVID, there’s certainly some of that, but not, unfortunately, the amoun t needed to make it a sustainable restaurant in and of itself. But it pairs very well with events.”

For years, those events were a hallmark of the Mercury.

“The Mercury used to be a place where people who are actually unable to fit into the culture went,” Gravagno says. “Homeless people, trans people before that was acceptable – the Mercury Cafe was the place that was a safe haven for them, and Danny just kind of doesn’t understand that whole philosophy. There’s a reason for everything at the Merc.” But more than that, though the Mercury revolved around Marilyn, it was self-sustaining because of the support she gave those who worked or held events in the space.

“The thing about working under Marilyn was that there was a very clear leader to this kind of anarchist thing, which was really helpful for things to be organized,” Gravagno adds. “Anyone who worked at the Mercury or held an event, they didn’t have to answer to anyone about how specifically they would need to do that, or how specifically they would need to make a dish or whatever, but if there were problems, there was a clear person to come to.”

Now, management is so hands-off that Gravagno has taken to solving problems on his own, going so far as to move the old, broken piano out and bringing in a new one after asking Newman if he would look into replacing the piano and not receiving much of a response, though Newman did approve Gravagno’s new, self-funded piano. Megenity still pays Gravagno to hold his Jazz Jam events at the Merc, which is how Gravagno afforded the piano in the first place.

The Megenity approach to creating a communal environment carried over into how she treated her employees. During her tenure, workers would get a free meal every shift and eat at a community table reserved for staff. During breaks, employees would hang out at the various events.

“It was kind of the aesthetic of the Mercury,” Martin says. “You sit down and you see workers acting like humans with you, and then getting on stage or dancing with you. So there wasn’t this separation of humanness between the worker and the community. The worker was a part of the artistic community.”

For a time during the pandemic, there were homeless encampments outside the door.

Brandon Johnson

Martin left the Mercury before much of the staff started pushing for a union. The workers went public with their unionization effort in July 2023 because of issues with scheduling, safety concerns not being handled appropriately and wages that weren’t sustainable, according to an Instagram post from the union.

“We have been and are currently dealing with extremely unstable hours and pay, which make our lives difficult to predict,” the post explained. “We feel disregarded, burnt out, and pushed out of jobs we enjoy and love.”

Anna McGee, who had been a server at the Mercury for six months at the time the union formed, says she and her co-workers had been having conversations about their concerns and wanted to unionize to protect themselves from retaliation for talking about their wages or their issues with the workplace. Those rights are protected by the National Labor Relations Act for those who attempt to unionize.

The workers believed unionizing was the best way to protect themselves and the community, McGee says; they unionized out of love for the Mercury and what it stands for, she adds.

“A union creates a safe and equitable space not only for the workers, but for the communities they serve,” McGee says. “If the workers are not being taken care of properly, or if their concerns aren’t being heard or their needs aren’t being met, then that ultimately trickles down into the customer side of things, the community side of things. In order to have a truly safe, holistic community space, everyone needs to be taken care of, including the workers.”

Employees asked for a say in decisions, wages of $21 per hour before tips, exploration of health benefits for employees who work less than full-time, regularly scheduled shifts and safety training. Newman had hired off-duty police officers as security guards to combat safety problems at the property, but some employees thought that overdose and de-escalation training would be more helpful and fit better with the mission of the Mercury.

Newman felt the union push came out of nowhere but says he was originally happy to meet with the workers and figure something out. He notes that the Mercury has always paid at least minimum wage and offered family leave and overtime as required by state law.

At first, McGee says, things went well and Newman seemed open to hiring safety trainers for the staff. But after a few weeks without any real action on Newman’s part, the employees filed for an election with the National Labor Relations Board, which they won in August 2023.

The Mercury is underwater financially, Newman says, and simply doesn’t have the funds to increase wages or spend any more money on lawyers for a union negotiation.

Union members say Newman has been unwilling to consider any of their proposals or sit down in a room to negotiate since this past August, despite multiple requests to do so. They say their initial demands are jumping-off points for negotiation, but that the owners haven’t even been willing to tentatively agree to a single contract item.

According to Newman, set scheduling just won’t work because of the space’s status as a venue, with some nights booked and others unbooked. He says he doesn’t think the union members were negotiating correctly, as they didn’t accept his team’s counter-offers or give his team their entire, written-out, desired contract language to work with.

Newman says that’s why the two parties haven’t yet reached a contract. But the union members see it differently, and on October 29 they called for a boycott of the Mercury, asking people not to go there and organizers not to hold events there until the owners took steps toward negotiating and implementing a union contract by the end of 2024.

Baby Raves have been a hit at the Merc.

Mercury Cafe

If it were up to Megenity, the workers would have been unionized years ago; she tried to get the Industrial Workers of the World to come help her employees unionize in the 1990s. Because she was the manager of the Merc, however, she couldn’t initiate the process, and her workers at the time were ambivalent.

Today Megenity says she’s pro-union but anti-boycott.

“I don’t support the boycott – I support the kitchen & bar workers and the artists & musicians who work there now,” she wrote in a public statement last month.

Her words echo a common theme among those who disagree with the boycott: Many of the people who pushed for the boycott are no longer working at the Mercury.

Current Mercury employees made a public statement of their own, noting that there are ten union employees currently working at the Merc who are negatively impacted by the boycott.

“Our staff relies on events, shifts and tips to survive, and we all feel threatened and scared for our livelihoods because of the actions of the union that were pushed through without all of us having any say in the matter,” those employees wrote.

But those calling for the boycott say the reason they don’t work at the Mercury anymore is because they were fired for being vocal about their involvement in the union. McGee and Mia Mainville both claim they were removed from the schedule without notice.

“Danny just cut everybody’s hours,” Mainville says. “Danny did a really great job of removing anybody aligned with the union from the actual workplace by not scheduling them.”

Union members have filed Unfair Labor Practices complaints with the National Labor Relations Board, claiming they were illegally removed from the schedule for their union involvement. But Newman says no one should have been surprised by the cuts, because he’d told the staff exactly when the money would run out. After that, the business would only schedule people when there were also events.

What was once a venue with expansive daily hours is now only open when events are scheduled, though Newman says they try to host at least one event at the Merc Tuesday through Sunday.

“There is no money,” Newman says. “I stupidly kept everyone on the schedule for a full year. I knew how much money we had borrowed, when it was going to be gone, and instead of saving that up and extending the timeline, I just kept paying people.”

But past and present employees question whether Newman’s financial claims are true, and filed an additional ULP claim over ownership’s refusal to share financial documents with the union. Under the National Labor Relations Act, if an employer says cuts to staff during contract negotiations are due to a lack of funds, then the union is granted the right to view company finances.

“A boycott is an extreme action to take,” McGee says. “I fully acknowledge that. We chose that option because we have exhausted all other options to get Danny and ownership to sit down at the bargaining table as they are legally obligated to do.”

Many, like Ivey, have moved their events out of the Mercury in solidarity with the union. But others, such as Gravagno, have not. He says that he might have done so if he’d had advance warning from the union, because he believes in what they are trying to do – but he also relies on the weekly events for income.

Newman says the calls for a boycott are akin to “kicking the Merc while it’s down.” While some people and events have joined the boycott, the action has also educated others on just how dire the situation is at the Mercury. As a result, some have come in to support the business.

“There’s nothing more sinister going on than people wanting their jobs and wanting to be paid fairly and accurately,” Mainville says. “I wish more people would put themselves in our position and think if your boss came to you and just said, “Okay, you need to leave right now,’ and you ask, ‘When am I going to come back?’ and they just don’t answer you, how frustrating that would be, how threatening to your livelihood that would be.”

The Jazz Jam continues every Friday at the Marc.

Brandon Johnson

Now the livelihood of the Merc is threatened, too. Newman says the union and boycott are complicating the potential sale that he and his partners began exploring earlier this year, at the height of Kruzick’s health scare.

“It’s not necessarily that we want to sell, and it’s not necessarily that we need to sell, it’s just that we need some help,” Newman says. “Through this process, a whole bunch of really interesting potential partners and stuff like that have emerged. … We are not going to sell to a developer.”

The asking price is $2.5 million, though Newman says he’d be happy to lease the place to someone who could put in the time and attention the Merc needs if a sale isn’t possible. Turning the business into an artist/employee cooperative is on the table, as is making the Mercury a nonprofit. He adds that he offered the employees the chance to form a co-op to buy the business when they first unionized, but they didn’t want to do so.

At this point, Newman says, it’s likely the Merc will add partners rather than being sold outright.

Gravagno says he’s grateful that Newman hasn’t sold to someone who would shutter the business or maybe even bulldoze the building. That’s one thing on which everyone can agree: The Mercury must live on.

“Denver needs consistency, and we’ve lost so many places,” Ivey says. “I’m hoping that [the Merc] does find that renaissance…so that we can, especially during this time, have one safe space in Denver.”

In her November statement, Megenity said it is her wish that the Mercury’s next chapter could be worker-owned or a co-op format. She wants the owners to be truly present at the business as owner-operators.

Gravagno, Fordyce and Martin are part of a group of former workers who wanted to join together to purchase the business, but when Fordyce and her husband met with the current owners, they found the costs were just too high for their group.

“We’re looking at creating more of a Merc-esque offshoot,” Fordyce says. “A potentially nonprofit arts, slow-food space that’s run on these principles that can provide an additional level of access for Denver’s art, culture and activist community in the spirit of the Mercury. … What is the Mercury? Is it the building? Because if it was the building, it would not feel the way it has the last four years.”

Since Megenity’s philosophy moved through many locations before the Mercury landed on California Street, the group believes it could bring her legacy to life elsewhere.

How to maintain Megenity’s legacy while ushering the Mercury into a new era is something the owners still haven’t figured out, Newman admits.

“I got into this never thinking we were going to replace Marilyn,” he says. “We very, very much have learned that this place is Marilyn. … There’s a lot of big changes because of that: going from this place being the creation of somebody to it has been created, and how do we keep it going without that somebody being the force all the time?”

That’s a question that everyone hopes can be answered before the jazz ends at the Merc.