Jay Vollmar

Audio By Carbonatix

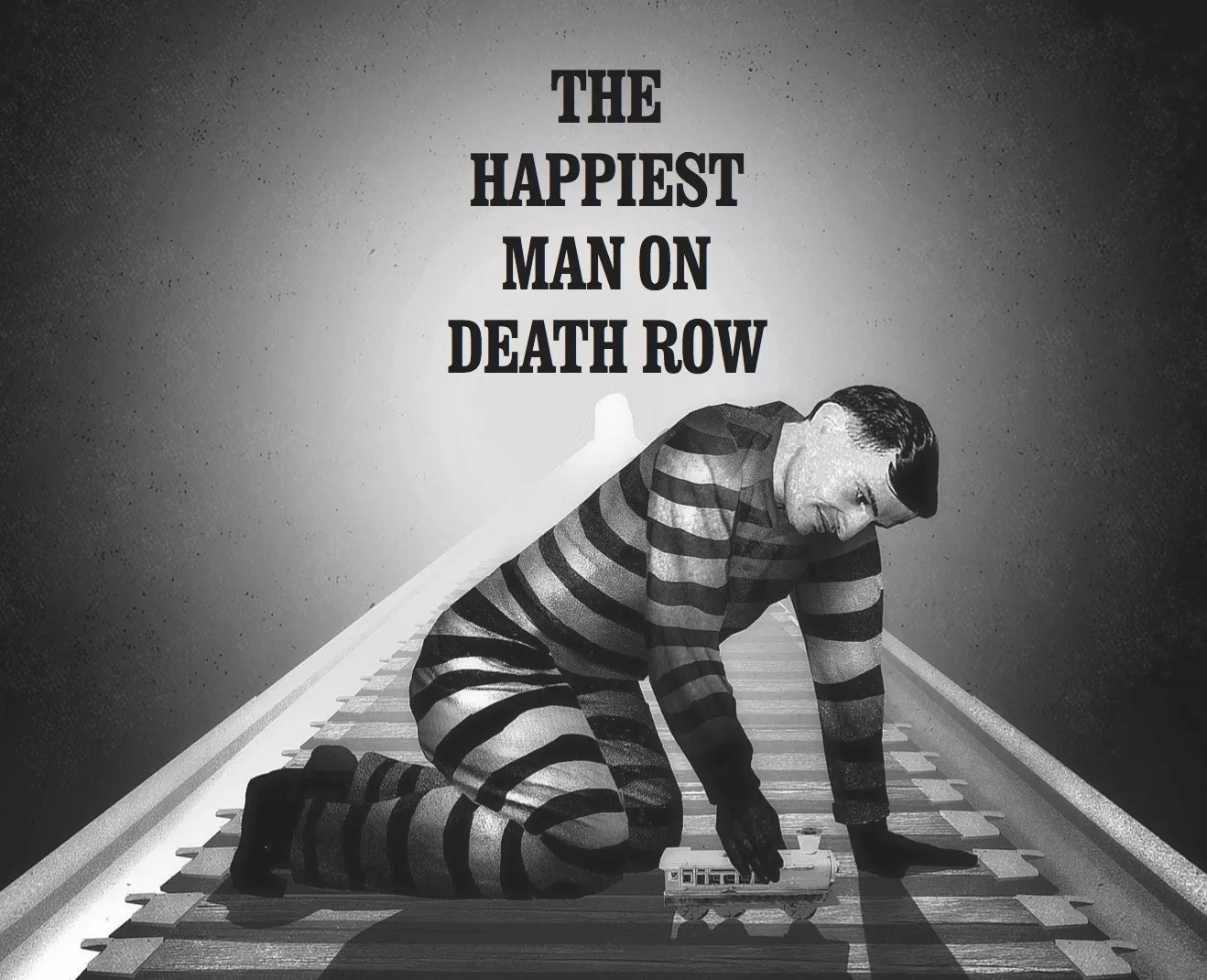

Joe Arridy didn’t ask for a last meal. It’s doubtful that he even understood the concept.

He was 23 years old and had an IQ of 46. He knew about eating and playing and trains, things you could see and smell and experience. But abstractions, like God and justice and evil, eluded him. The doctors called him an imbecile – in those days, a clinical term for someone who has the mental capacity of a child between four and six years old, someone considered more capable than an idiot but not quite as swift as a moron.

The newspapers of the 1930s had other names for him. “Feeble-minded killer.” “Weak-witted sex slayer.” “Perverted maniac.”

Like Ricky Ray Rector, the lobotomized Arkansas killer who told his executioners that he was saving a slice of pecan pie in his cell “for later,” Arridy had trouble grasping the finality of what was about to happen to him. The mystery of death had baffled much deeper thinkers than Joe Arridy. How could he be expected to fathom the ritual of a last meal?

So when they told him he could eat what he wanted, he asked for ice cream. Lots of ice cream. Ice cream all day long. Ice cream and his toy train – that was Joe’s idea of fun.

Hour after hour, day after day, Arridy would reach through the bars of his cell and send his wind-up train chugging down the corridor of death row in the Colorado State Penitentiary. Other condemned prisoners would reach out from their cells, cause diversions and train wrecks and rescues that made Arridy laugh, then send the train back to its delighted owner for another go-round.

But on the last day, the day of ice cream – January 6, 1939 – the train’s busy schedule was interrupted by a farewell visit from Joe’s mother, aunt, cousin and fourteen-year-old sister. His mother shuddered and sobbed. Dry-eyed and perplexed, Joe stared at her. Then the women left, and Joe returned to his train.

That evening, the warden, Roy Best, and the prison chaplain, Father Albert Schaller, dropped in to prepare Arridy for the journey ahead. Minutes earlier, the Colorado Supreme Court had denied a final petition for a stay of execution by a vote of four to three, and Governor Teller Ammons had ordered Best to proceed with the sentence. Father Schaller told Arridy that he would have to give up his train, but he’d be swapping it for a golden harp.

That was fine with Joe. He doled out his favorite possessions on the spot: the train to another prisoner, a shiny tin plate to Warden Best, a toy auto to the warden’s nephew.

Best, Schaller and Arridy began the slow walk to the gas chamber, located on a hill above the penitentiary. There was no last-minute call for pardon from the governor’s office, a call that could have saved the life of Joe Arridy – and saved the State of Colorado from committing one of the most shameful executions in the nation’s history.

The call didn’t come that night. It wouldn’t arrive for another 72 years.

********

In the spring of 1992, a friend sent Robert Perske a copy of “The Clinic,” a long out-of-print poem by an obscure poet about a forgotten execution. It began:

The Warden wept before the lethal beans

Were dropped that night in the airless room

The poem went on to describe a doomed man who did not weep, but simply played with his toy train. “The man you kill tonight,” the warden writes, “is six years old. He has no idea why he dies.”

Perske had grown up in south Denver and served as a Navy radio operator in World War II. After the war, he’d become a Methodist minister and worked for eleven years as a chaplain at the Kansas Neurological Institute, an institution for children with intellectual disabilities. As efforts to end the warehousing of the disabled gained momentum in the 1960s and 1970s, Perske became a self-described “street-court-and-prison worker,” advocating for this vulnerable population’s right to live in the community. He also became deeply involved in challenging false confessions from mentally disadvantaged suspects, admitting to crimes they had not committed.

The poem about the train haunted Perske. Had there actually been such a case? He tracked down the poet, Marguerite Young. She told him that, yes, the poem had been inspired by a newspaper article she’d read, but she couldn’t recall the details. After some additional sleuthing, Perske was stunned to discover that the execution had taken place a hundred miles from where he grew up. He had been eleven years old when the “lethal beans” – cyanide pellets, plunged into acid to produce a deadly gas – dropped for Joe Arridy.

Arridy was from Pueblo, and he’d been found guilty of one of the most horrific crimes in the tough steel-mill town’s history: the rape and ax murder of fifteen-year-old Dorothy Drain, the daughter of a prominent local official and granddaughter of a former state legislator. News accounts described how Arridy, an escapee from a home for the feeble-minded, had confessed to the attack, re-enacted it for police at the crime scene and fingered his partner, Frank Aguilar, a Mexican immigrant. Both men got the gas for their deeds. Then the story faded from the headlines, replaced by fresh atrocities.

Perske had to know more. He spent many hours cranking microfilm readers in libraries. He studied long-shelved court records and commitment papers and unearthed confidential files and notes about Arridy’s mental status and his life in an institution. The more he read, the less sense it all made. There was plenty of evidence in the case, but precious little of it pointed to Arridy, and nothing was quite what it seemed – least of all the so-called confession.

In 1995 Perske published a modest but solidly researched book about the Arridy case, Deadly Innocence? “All I wanted to do was get the facts down,” he says now. “I’m not a brain. I’m not a great writer. But I’ve been able to document 75 cases where people with disabilities were coerced into confessions and convicted, then found to be innocent. This is the most telling of all the cases I’ve worked on.”

Although it was well received among disability activists, Perske’s book drew little attention elsewhere when it first appeared. Yet its publication set a process in motion that would lead to unexpected places. To a screenplay by a Trinidad writer about Arridy’s life and death, now under option with a film-development company. To a grassroots campaign to clear his name, launched by a group calling itself Friends of Joe Arridy. And to the first posthumous pardon in Colorado’s history, issued by Governor Bill Ritter last year, in the final days of his administration.

America’s rites of capital punishment have changed greatly in the past 75 years. A decade ago, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that severely retarded prisoners cannot be executed, regardless of their crimes. Such a prospect would be particularly unlikely in Colorado, which has executed only one man in the past four decades. Yet in the wake of the Aurora theater shootings, the state’s death penalty is getting dusted off once again, amid speculation that the only possible defense for suspect James Holmes may be an insanity plea.

Faced with no viable legal alternative at the time, Arridy’s lawyers contended that he was insane, too. The similarities between the two cases end there. Yet the Arridy case remains a cautionary tale for the ages – a story of grandstanding cops and a rush to judgment, an outraged community and a vengeful press, a serial killer and the perfect patsy.

It’s a tale told by an imbecile, full of sound and fury, signifying justice gone insanely, fatally wrong.

Found wandering the Cheyenne train yards, Joe Arridy promptly confessed to a notorious Pueblo murder – and other crimes he couldn

Historical image from 2012 print edition of Westword.

Around ten in the evening on August 15, 1936, Riley and Peggy Drain said goodnight to their two daughters and drove from their Pueblo bungalow to a benefit dance at a local nightclub. They returned a few hours later to find their world violated and destroyed.

As they headed to their front door, Peggy noticed that the light she’d left on in the front room was turned off. Riley, a local supervisor for the Works Project Administration, rushed to the back bedroom that the girls shared. Their bed, as a prosecutor would later put it, was “literally soaked with human gore.”

Fifteen-year-old Dorothy Drain lay motionless on the bed, blood pooling from a deep gash in her skull. Curled up next to her sister, twelve-year-old Barbara was unresponsive but still alive. The coroner would determine that Dorothy had been raped and suffered a fatal blow to the brain from a sharp weapon, such as an ax – quite possibly killed first, then sexually assaulted. Barbara had been bludgeoned in the head, perhaps with the blunt end of the ax, and was in a coma.

The grim scene was remarkably similar to another savage attack on two women sleeping in a bed together that had occurred just two weeks earlier, in a home three blocks away. Sally Crumpley, a 72-year-old woman visiting from Kansas, had been killed while she slept; her host, 58-year-old Lilly McMurtree, had been badly injured. Both women had been struck in the head.

The same night Dorothy Drain was killed, two women in the neighborhood claimed to have been grabbed from behind on the street by a short, swarthy man, described in news accounts as “Mexican,” but they had fought him off. Clearly, there was a sex maniac on the loose in Pueblo.

But the Drain crime scene, like the one at the McMurtree house, yielded few clues. Whoever had attacked the girls had entered through the unlocked front door, doused the light, and lit matches to illuminate the way to the bedroom. Police found some smudged fingerprints and a heel print.

Any useful evidence outside the house was quickly obliterated the next morning by the crowds of people milling around, gawking and talking about a “necktie party” for whoever did this. The girls’ grandfather, Perry Dunlap, was a former state senator with many friends in the community, and none of them were inclined to take lightly these attacks on Pueblo womenfolk.

“By 9 a.m. word of the tragedy had spread across the city, and hundreds of excited townspeople were standing in front of the residence,” Pueblo police chief Arthur Grady wrote in an article for a true-crime magazine, published just months after the killing. “Pueblo has a population of about 50,000, and by 10 a.m. it seemed as though 49,000 of them had swooped down on Stone Avenue.”

Grady’s men grilled swarthy ethnic types and former WPA workers who might have a grudge against Riley Drain, checking alibis. Police departments across the Front Range rousted vagrants, known perverts, immigrants and suspicious characters of all kinds. The manhunt stretched all the way to Cheyenne, Wyoming – where, eleven days after the Drain murder, Sheriff George Carroll decided to question a bedraggled young man who’d been found by Union Pacific bulls that afternoon wandering around the railyards.

The man’s name was Joe Arridy. He was 21 years old, 5′ 5″, 125 pounds, with a dark complexion – a description not unlike that of the man seen assaulting women near the Drain home, although Arridy’s heritage was Mediterranean, not Mexican. But what caught Carroll’s attention was that the kid said he’d come by train from Pueblo.

A former cowboy and newspaper publisher, Carroll was a bluff, confident lawman with a reputation for breaking big cases – and courting the publicity that went with them. He’d helped to track down Ma Barker and several members of her gang after the murder of one of his deputies. In 1933, he’d cracked the kidnapping of Claude K. Boettcher II, heir of a wealthy Denver family, locating a South Dakota hideout and springing Boettcher unharmed. As the Arridy case would prove, he still had a few headlines left in him.

It took Carroll only a few moments of conversation with Arridy to realize that he wasn’t the sharpest knife in the drawer. His speech was slow, his words short and simple. But he seemed willing to talk. Carroll would later tell reporters that he asked the man if he liked girls. Arridy said he liked them fine.

“If you like girls so well, why do you hurt them?” Carroll asked.

According to Carroll, Arridy replied, “I didn’t mean to.”

Carroll questioned Arridy for almost eight hours over the next two days. He would later testify – from memory, since there were no notes, much less any witnesses, for most of the interrogation – that Arridy had volunteered, in his halting way, a harrowing story about the night Dorothy Drain died. He’d spied on the girls from the bushes outside, seen their parents leaving and snuck inside. He’d hit them in the head, taken his clothes off, assaulted Dorothy, dressed and left.

Certain elements of the story made no sense. At first he talked about hitting them with a club, then changed it to a hatchet. He was unable to say where he got the hatchet. But Carroll insisted that Arridy provided details about the Drain house – the arrangement of the rooms, the color of furniture and the walls in the girls’ bedroom – that only someone who had been there would know. He arrested Arridy and called Chief Grady to tell him he had a “nut” who couldn’t read or write but seemed to know all about the Drain case.

“He’s either crazy or a mighty good actor,” Carroll added.

This wasn’t the welcome news Carroll expected it to be. As the sheriff soon discovered, Grady already had a suspect named Frank Aguilar who looked awfully good for the Drain job. Aguilar had caught detectives’ notice by showing up at Dorothy’s funeral in overalls and going twice through the line of mourners at the casket. He’d also approached Riley Drain and tried to hand him a fistful of nickels to “help the family.”

The officers arrested him. They learned that Aguilar had worked for Drain on WPA projects and had been discharged by him. He had seen the girls at work sites. At his house police found news clippings about sex slayings around the country and pictures of nude women. In a bucket, under some rags, was a hatchet head with distinctive nicks in it that seemed to match up with the wounds inflicted on Dorothy Drain.

Aguilar insisted he was innocent. His aged mother said that he was home that night. But the evidence suggested otherwise. Even some fingernail scrapings taken from Aguilar contained blue chenille fibers consistent with the bedspread in the girls’ bedroom.

Still, Sheriff Carroll had found in Joe Arridy another promising suspect. And this one was dying to confess.

Chief Grady, District Attorney French Taylor and other investigators headed to Cheyenne. Taylor brought the hatchet head recovered from Aguilar’s house. Asked if he recognized the hatchet, Arridy said that it belonged to someone named Frank. The story had shifted overnight; now Arridy was claiming that he’d committed the crime with Frank, that it was Frank who’d hit the girls with the hatchet. He offered little other useful information, and Taylor told reporters that the suspect seemed to be hung over “from use of marijuana or something similar.”

Grady had to adjust his notions of ax murderers on the spot. He’d been pursuing one fiend. Now it seemed he had two. “It is indeed a rare occurrence when two sexually perverted maniacs join forces outside an institution, and even a rarer occurrence when they combine to commit a sexual crime,” he wrote in an article for Official Detective. “The Drain murder undoubtedly will find a place in medical history as one of the most unique crimes of the ages.”

Amid highly publicized security, Arridy was taken to Pueblo and escorted through the Drain home, where he re-enacted the scenario he’d provided about he and Frank turning off lights and attacking the girls. Then he was taken to police headquarters for a confrontation with Frank Aguilar, witnessed by several officers.

“That’s Frank,” Arridy said.

Aguilar studied his accuser. “I never seen him before,” he said.

Sheriff George Carroll called Arridy insane – but changed his opinion at trial; a jury took 28 minutes to find Frank Aguilar guilty of killing Dorothy Drain and sentence him to death.

Historical image from 2012 print edition of Westword.

The more Bob Perske learned about who Joe Arridy was, the more convinced he became that Arridy could not have done the things the police insisted he had. The greater mystery was why anyone in authority at the time, who had access to all the same information and more, could have believed he had.

Arridy was born in Pueblo in 1915, the son of Syrian immigrants who were also first cousins. His father, Henry, worked in one of Colorado Fuel and Iron’s foundries. The couple had several children who died young. At least one of Joe’s brothers who did live, George, was considered mildly retarded – or, as the doctors put it, a “high moron.”

Joe was a more severe case. He didn’t utter his first words until he was five. After one year of elementary school, his parents were informed by the principal that he was incapable of learning and should stay home. For several years, he did just that – hammering nails, making mud pies, keeping mostly to himself. When he was ten, his parents were persuaded to commit him to the Colorado State Home and Training School for Mental Defectives in Grand Junction.

Perske found the tests Joe took as part of his evaluation at the school. They indicate that he could not correctly identify colors or explain the difference between a stone and an egg. He couldn’t repeat a sequence of four numbers. He was described as “slow,” with a “stupid, distant look.” His examiners considered his father to be of average intelligence; his mother, Mary, was described as “probably feeble-minded.”

Henry Arridy regretted putting his son in an institution and took him home after only ten months. But Joe had little supervision there; Henry lost his job and was soon in jail for bootlegging. Joe wandered all over town. At fourteen, he came to the attention of a juvenile probation officer, who wrote a furious letter to the superintendent of the state home, demanding that he be recommitted.

“He is one of the worst Mental Defective cases I have ever seen,” the officer wrote. “I picked him up this morning for allowing some of the nastiest and Dirtiest things done to him that I have heard of.”

According to the officer, Joe had been “manipulating the penis of Negro Boys with his mouth” and allowing said boys “to enter the ‘dirty road’ with their penis.” (“I would be more technical,” the officer explained apologetically, “but do not know the terms.”) In another time, Arridy might have been deemed an at-risk teen who’d been sexually exploited by older youths. But in 1929, he was simply a pervert who had to be locked away.

A court sent him back to the state home. He spent the next seven years there, where he learned to wash dishes, mop floors and do other simple chores. The superintendent, Dr. Benjamin Jefferson, regarded him as highly suggestible and vulnerable, often taken advantage of by other boys; at one point, he confessed to stealing cigarettes when he clearly wasn’t the culprit. His family asked several times if he could be sent home, but Jefferson responded that Joe’s “perverse habits” made it advisable to keep him there. He didn’t try to peep at the girls, like some of the boys, but he was inclined to “masturbation, sodomy and oral practices on other boys of his erratic type,” Jefferson noted. “His affection is always towards other boys…never towards the female sex.”

Shortly after he turned 21, Arridy ran away from the state home, only to return on his own. Then he disappeared again. He was joined in the Grand Junction train yards by three other walkaways. Five days before the Drain murder, they hopped an eastbound freight. The train pulled into Pueblo the next day. That night, they rode it back to Grand Junction. According to one other escaped youth, Arridy was still in the Grand Junction railyard on August 13, 48 hours before the murder. The same youth insisted that he and Arridy didn’t make it back to Pueblo until the evening of August 16 – the day after the murder. Then Joe rode the rails alone to Denver and Cheyenne, where Carroll arrested him.

The alibi witness was never called to testify on Arridy’s behalf. Perhaps his account was considered unreliable; he was, after all, another “feeble-minded” unfortunate. But how reliable, Perske wondered, was the confession Arridy made in Cheyenne?

The circumstances were certainly suspicious. No one heard the bulk of Arridy’s story but Carroll, who made no effort to record it. Arridy started out talking about a club, then it became a hatchet; Carroll knew from the newspapers that it had to be an ax. Arridy didn’t start blaming “Frank” for the murder until after Carroll talked to Chief Grady and discovered that Frank Aguilar had already been arrested. And how likely was it that Arridy, who still couldn’t get the names of colors right, had provided a detailed description of the Drain home – unless he was prompted in some way?

“I know an awful lot about the Joe Arridys of this world because I’ve worked with them in the community all my life,” Perske says. “Joe, he never gave any data. This was a case of a sheriff who saw one more chance to be famous.”

Much of the “data” Arridy did provide in his confession turned out to be wildly untrue. He said he ran from the Drain home to his family’s house, where his mother and sister beat him and kept him in an upstairs room for days. He provided several addresses for his family, none of which panned out; the detectives who tried to check out his story soon learned that his family hadn’t seen him in years, and that the bungalow in which they lived had a dusty attic that hadn’t been entered by anyone for a long time.

Arridy also confessed to other recent assaults. A woman in Colorado Springs said that a picture of Arridy in the newspaper looked exactly like the man who’d attacked her on August 23, and Arridy readily admitted to the crime. The only problem was that investigators soon determined that he arrived in Cheyenne three days before the Springs assault and stayed there, working with a Union Pacific kitchen crew until he was arrested on August 26. Cigarette thefts, rape, murder – the agreeable Arridy would have ‘fessed up to the Lindbergh kidnapping if they asked the question right.

Yet Arridy wasn’t the only one telling strange tales about the Drain murder. After first denying that he knew Arridy, Aguilar changed his story, too. Several days into his interrogation, Aguilar gave a statement in which he claimed to have met Arridy in a park a few hours before the murder. The two of them plotted the attack on the Drain girls – Aguilar had already learned that the parents were going out that night – and then carried it out together. Much of the “confession” consisted of terse yes-no answers to leading questions (“Then Joe assaulted the big girl, didn’t he?”). Aguilar later disavowed the whole thing, claiming that he’d been threatened and bullied into signing it.

Coerced or not, the statement reeked of desperation, a diversionary tactic by a man who could feel the noose tightening and was eager to share the blame. Perske found it ludicrous. Even if it could be positively established that Arridy was in Pueblo the day of the murder, one would have to believe that Aguilar, the prime suspect in a series of brutal but carefully planned attacks on women, had impulsively recruited a dull-witted stranger, fresh off a boxcar, to join him in his latest homicidal venture. A unique crime of the ages, indeed.

Yet what most impressed Perske wasn’t Aguilar’s ever-changing story; it was Joe’s own words. He was allowed to speak for himself in court only once, for a few brief moments in a sanity hearing, during which the defense argued that he was too imbecilic to know the difference between right and wrong.

In response to a series of questions from the prosecutor and his own attorney, Arridy said he didn’t know who Franklin Roosevelt was – or George Washington, for that matter. He didn’t know Dorothy Drain or Frank Aguilar. He didn’t know what a hatchet was. He didn’t know why he was in court. He did know the difference between a dime and a nickel, and he did recognize the doctors from the state hospital who had been on the stand before him, “talking about me.”

“What about you?” prosecutor Ralph Neary asked.

“Oh, about something,” Arridy replied.

“Don’t you know what they were talking about?”

“No. Forgot.”

“Can you tell me anything they talked about?”

“I don’t think so.”

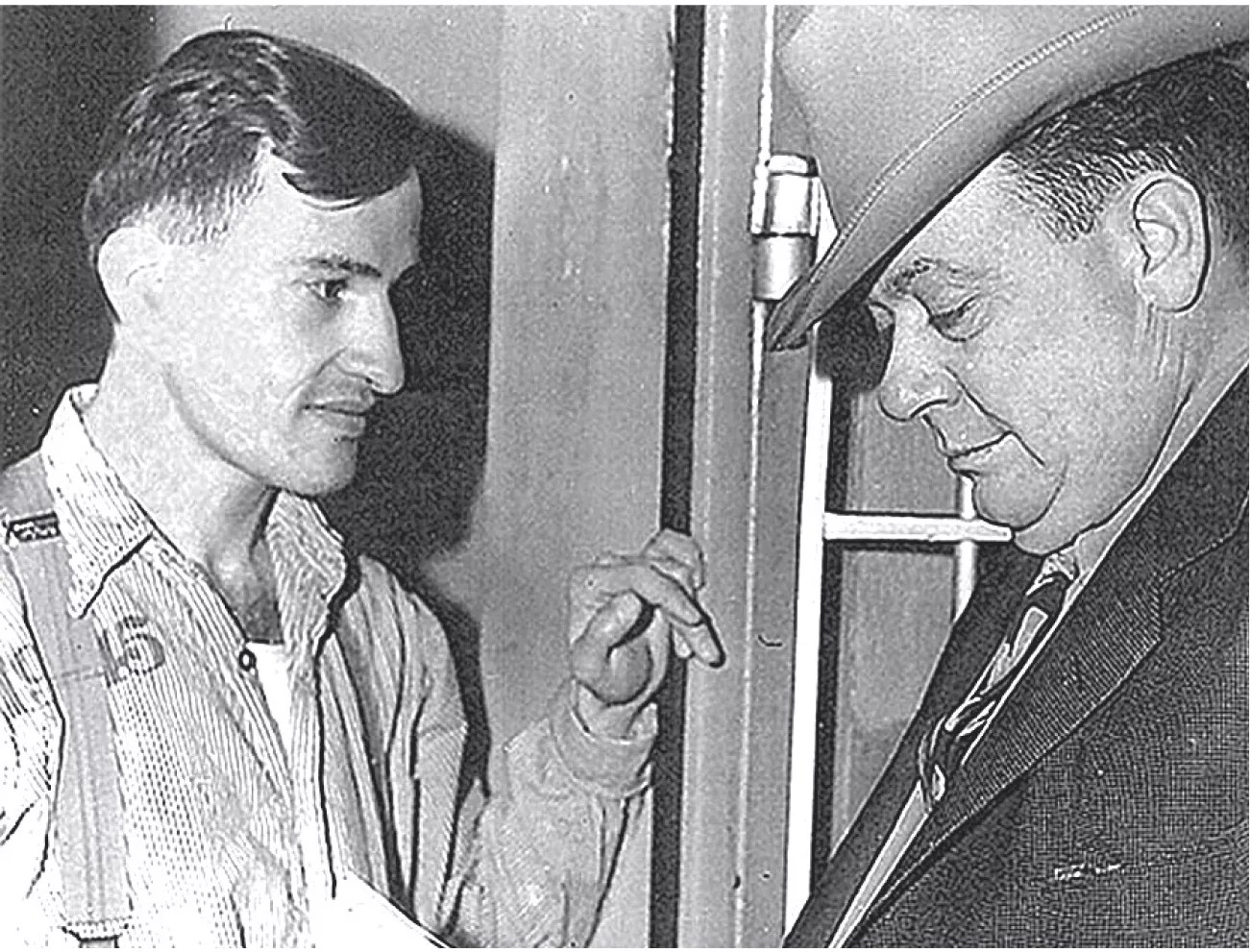

Warden Roy Best reads the death warrant to Arridy at his cell door, shortly before his execution.

Historical image from 2012 print edition of Westword.

The murder of Dorothy Drain touched off waves of hysteria and political recrimination across Colorado, much of it directed at the phantom menace of train-hopping, sex-crazed mental defectives who needed to be put away, if not put down. Governor Edwin “Big Ed” Johnson fired off a telegram to Ben Jefferson, demanding a full report on the Arridy boy and an explanation why “this pervert” hadn’t been transferred from the low-security institution in Grand Junction to the state asylum months ago. “Have you any more dangerous persons in your school who should have closer supervision than you are equipped to give?” he blustered.

PEOPLE OF COLORADO BLAMED FOR IMBECILES RUNNING LOOSE, blared a headline in the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel. The story claimed that the state had six times more imbeciles than could fit in existing institutions: “Some of them are dangerous criminals, and some of them are sex perverts…. Hundreds of them are hidden in homes under the watchful care of loving relatives.”

Chief Grady had vowed there would be no lynching; Arridy and Aguilar were kept in cells at the state prison at Cañon City, rather than the Pueblo jail, out of fear of mob violence. But the climate hadn’t improved by the time the cases went to trial.

Aguilar went first. His attorney, Vasco Seavy, labored unsuccessfully to exclude his client’s multiple confessions, including one Aguilar made to Riley Drain when the grieving father joined in the prison interrogations. But it was another member of the Drain family – young Barbara, who’d spent weeks in the hospital recovering from the beating she received – whose testimony made the case. At DA Taylor’s urging, the girl stepped down from the stand, stood in front of Aguilar, and identified him as the man she saw in her bedroom the night she and her sister were attacked. She didn’t say anything about a second man.

That night, Aguilar apparently admitted his guilt to his attorney. The next day, Seavy tried to change his client’s plea from not guilty to “not guilty by reason of insanity.” The judge refused. The jury took all of 28 minutes to return with the death penalty.

Months later, Aguilar admitted to killing Sally Crumpley, too. By some accounts, police also had a strong case against him for the ax slaying of another Pueblo woman that occurred two years before the Crumpley and Drain murders, in the same neighborhood. He never went to trial in the earlier cases, probably because he was already facing death for what he did to Dorothy Drain. Yet none of these revelations, indicative of a serial killer who worked alone, could derail the prosecution of Joe Arridy.

It was an express, bound for death row.

At Arridy’s sanity hearing, a battery of doctors testified about his mental incapacity. Some hedged, though, on whether that meant he couldn’t tell right from wrong; the reasoning seemed to be that you need to have a fully functioning brain to become deranged, so an imbecile can’t really go nuts. Of greater weight, perhaps, was the testimony of Sheriff Carroll, who claimed that Arridy “shed copious tears” of remorse while confessing to the murder, like a child who knew he’d done wrong. The jury found him sane.

Despite that setback, Arridy attorney Fred Barnard was determined to pursue an insanity defense at trial. He didn’t attack the evidence. He didn’t call Barbara Drain to testify that she hadn’t seen Joe Arridy in her bedroom that night. And, even though Barnard described his client as a “confession maniac” who would admit to anything, the defense lawyer didn’t go after Sheriff Carroll, who took the stand five times and demonstrated amazing recall of a confession that was never written down. Carroll’s most intriguing admissions came at the prompting of prosecutor Neary, not the defense.

“[Arridy] did not at any time give you a narrative story of what happened, did he?” Neary asked.

“Not very much,” Carroll replied.

“You had to, what we commonly say, ‘pry’ everything out of him?”

“To a certain extent, yes, sir.”

Carroll was practically the whole case. Police had failed to match the fingerprints found in the home to Arridy. The women grabbed on the street that night failed to identify him as their attacker. Aguilar’s disputed confession implicating Arridy was never introduced. There was a grimy shirt found in the Cheyenne train yards that might have had blood on it and apparently had been worn by Arridy at some point, but the stains were never tested.

The only physical evidence linking him to the crime scene was a single dark hair recovered from the girls’ bedding, part of a bloody mass of hairs and fibers collected several days after the murder, stuffed in an envelope and sent to toxicologist Frances McConnell in Denver. McConnell testified that the hair was “identical” to hairs taken from Arridy, that only two people in 500 would have hairs that appeared that similar under a microscope. Yet McConnell also said that the hair’s owner was someone of “American Indian” extraction – an assertion that gives some idea of how haphazard the state of forensic hair analysis was in the 1930s, prior to the use of DNA.

A Pueblo pawnbroker testified that he’d sold a gun to Arridy the day of the Drain murder, placing him in town that day. But the man had originally claimed the purchase happened the day before the murder (when Arridy was supposedly still in Grand Junction), and the gun was never found. Like the hair, it was another loose end, something for the jury to puzzle over. Why would the pawnbroker lie? But then, why would a simpleton be buying a gun? How would a recent escapee from an institution get the money for such a purchase?

When it was the defense’s turn, Barnard brought in a procession of headshrinkers to testify that Arridy was legally insane. Superintendent Jefferson described Arridy as a chronic masturbator, but one who seemed to have no sexual interest in women and was easily led by others. He classified the boy as a “primary ament,” the product of a “diseased germ plasma that never was allowed to unfold” – in short, someone who wasn’t nearly as responsible for his actions as, say, a high moron.

The prosecution presented no experts to argue that Arridy was sane. Instead, various police officers were asked their opinion of the accused. They all agreed that he had a lower-than-average intellect but was of sane mind. Sheriff Carroll, who’d told reporters after the arrest that Arridy was “unquestionably insane,” now said there was no doubt in his mind that the man knew the difference between good and evil.

The jury found the cops more convincing than the eggheads. An experienced lawman like George Carroll surely knew a bad apple when he saw one. The panel retired for three hours and came back with a sentence of death.

The Pueblo Chieftain reported that Arridy took the news “unflinchingly.”

Or maybe he didn’t take it in at all.

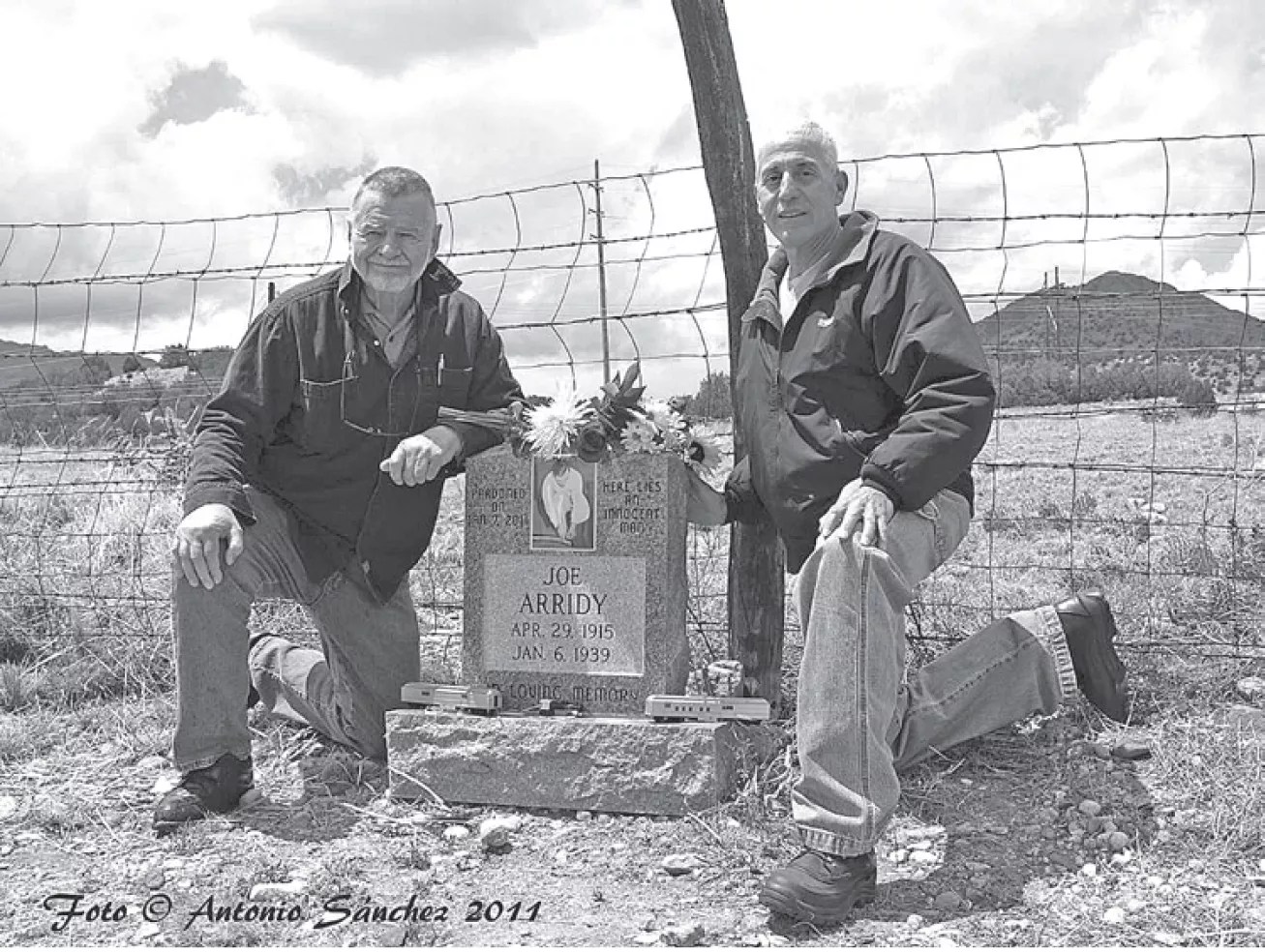

Author Robert Perske (left) and attorney David Martinez, who won a posthumous pardon for Arridy in 2011, visit his grave on Woodpecker Hill outside Can?on City.

Historical image from 2012 print edition of Westword.

First to trial, first to be convicted of the Drain murder, Aguilar also got the gas first. He did not go gently.

On his last day – August 13, 1937, an unlucky Friday – he had a hell of a row with his wife in his cell. His octogenarian mother collapsed and was taken to the prison hospital. He was hauled to the death house “whimpering and cringing,” the Denver Post gleefully reported.

It was one of the most heavily attended executions in state history. Riley Drain had a front-row seat as Aguilar bucked, strained against the straps and fought the cyanide gas for almost a full minute. One of the spectators, a Missouri Pacific railroad conductor, dropped dead of a heart attack just as Aguilar expired.

Reporters made much of the fact that Aguilar’s henchman, Joe Arridy, did not bid him farewell during his march from death row. But then, Arridy had told the men in court that he didn’t know Frank Aguilar.

That same day, Sheriff Carroll and the two railroad employees who nabbed Arridy collected a $1,000 reward for solving the case.

********

Like Sheriff Carroll, the warden of the Colorado State Penitentiary was a tough lawman who knew his bad apples. But Roy Best could see a world of difference between the likes of Frank Aguilar and little Joe Arridy.

A former state patrolman and driver for the governor, Best had been one of the troops called out to put down a bloody riot that all but gutted the pen in ’29. In the shakeup that followed, he became, at 31, one of the youngest wardens in state history. He would stay on the job for twenty years.

Best not only rebuilt the prison, he remade it, according to his own hard-nosed ideas about discipline and rehabilitation. He pushed for better sanitation, silent periods, individual cells, prison industries, an array of privileges that could be used to reward good behavior. He preferred to flog convicts who misbehaved rather than send them to solitary confinement. He befriended (and all but adopted) some of the prison’s most vulnerable inmates, including Jimmy Melton, who’d been tried as an adult for murdering his sister when he was twelve.

Arridy was one of Best’s special cases. The warden brought him picture books, a battery-powered toy car – and, toward the end of his stay, the toy train. “Joe Arridy is the happiest man who ever lived on death row,” Best told reporters.

The twenty months Arridy spent in Best’s domain were unlike anything he had known before. Taking their cue from the warden, the guards didn’t harass him. The other condemned men humored him and put up with his games. They didn’t call him a feeb, a pervert or, worse, a diseased germ plasma. Perhaps he reminded them of the children they had once been. To others, it may not have seemed like much of a life, but it was something like acceptance.

Yet when Bob Perske retraced those last months of Arridy’s life, he couldn’t help feeling that his subject had become a kind of afterthought in the Drain investigation, collateral damage in someone else’s scheme. He had been required for a specific purpose, to provide a confession implicating Aguilar, and now he was expendable.

“They needed Joe to get Aguilar,” Perske says. “But you couldn’t unring a bell. Once they had what they wanted, people just gave up on him.”

One man did not give up. Prominent Denver attorney Gail Ireland agreed to take on Arridy’s appeals at the request of Ben Jefferson, the superintendent of the state home. Correspondence between the two reveals that both men were convinced of Arridy’s innocence; but as a legal strategy, Ireland’s briefs didn’t contest “the fact that Arridy was present when the crime was committed.” Instead, Ireland challenged the finding that Arridy was sane. A man who is mentally incompetent cannot adequately defend himself at trial, Ireland argued, and cannot be legally executed in such a condition.

Ireland obtained nine stays of execution. The Colorado Supreme Court found his arguments intriguing, but, as Justice Norris Bakke opined, their job was to interpret “the law of the state as it now is, not under what we wish it might, or should, or may be at some time in the future.”

Arridy was less impressed. He scarcely looked up from his toys when told of the reprieves. He didn’t seem distressed when the petitions eventually failed, either. Death was not real, the way the train was. (Headline from the Chieftain: HE DIES FRIDAY BUT LAUGHS TODAY.)

Eleventh-hour appeals for another sanity hearing and for clemency from the governor failed, too. The day of ice cream arrived, and Arridy was persuaded to give up his train and say prayers with the chaplain, who recited slowly, two words at a time, so Arridy could repeat after him: “Our Father…who art…in heaven…”

The little man shook hands with the other doomed men and handed out his toys. A sparse crowd watched him head to the death house, flanked by Best and Father Schaller. Riley Drain had vowed to return to see Arridy executed, but he didn’t attend. Outside the chamber, Arridy was stripped to his socks and shorts. He smiled as the guards strapped him to the chair and Best patted his hand. Then he was alone in the room.

The gas swirled up from beneath the chair. He took three deep breaths and died.

Warden Best wept.

********

With few exceptions – Best, Ireland, a small circle of family and clergy and people of kindness and courage – the citizens of Colorado weren’t inclined to mourn Joe Arridy. A Denver Post editorial likened the execution to a mercy killing: “He never could have been anywhere near a normal human. Alive, he was no good to himself and a constant menace and burden to society. The most merciful thing to do was put him out of his misery.”

For some, the misery didn’t end there. George Arridy was kept in a state institution for years, despite his plaintive written pleas and demonstrated good behavior, out of fears about the public uproar that would result if the “high moron” brother of an executed killer was allowed to run loose.

Although colleagues had warned him that taking on the Arridy appeal might blight his career, Gail Ireland went on to serve four years as Colorado’s attorney general. Roy Best enjoyed a long and popular reign as warden before getting suspended for whipping prisoners in 1952. He was acquitted of embezzlement and civil-rights violations but died shortly afterward. George Carroll grabbed his last headline in 1961, when he expired at a Cheyenne rest home.

The story of Joe Arridy might have vanished forever at that point – if not for a poem about a condemned man and his toy train, which led to Robert Perske’s book, which led to so much more.

Trinidad journalist Daniel Leonetti read about Perske’s book when it was first published and immediately got in touch with the author. Over the years, the two have swapped research and theories, and Leonetti has written a screenplay about the case, focusing on Gail Ireland’s efforts to save a client who doesn’t even understand what is happening to him. The script is now under option by Keller Entertainment Group.

“He was a righteous man,” Leonetti says of Ireland. “If he saw something was wrong, he had to do something about it – despite his social status. Even his wife questioned him when he took this on.”

Perske’s work was also a source of inspiration for Craig Severa, an advocacy specialist for The Arc of the Pikes Peak Region, a nonprofit serving people with developmental disabilities. Severa recalls going with Perske to visit Arridy’s grave in the prison cemetery. The only marker was “a rusted-out motorcycle license plate on a steel pole” that had the deceased’s name as ARRDY. Severa decided to raise money for a decent headstone, hitting up judges, attorneys and community groups.

Along the way, Severa talked to longtime residents in Cañon City and learned some local folklore about Arridy’s grave. People said it glowed at night because it was the resting place of a child.

Severa believes Arridy’s story still has bearing today, when many chronically arrested street people have some degree of mental impairment. He trains police cadets how to recognize and deal with suspects with disabilities. “I’ve got one guy I’ve gone to court with 42 times,” he says. “But the system has become more understanding. There are judges who are absolutely great in Colorado Springs. The danger comes when you’re dealing with guys who have a verbal IQ of 72, but to the police they look completely normal.”

By the time the new tombstone was unveiled, in 2007, a small group calling itself the Friends of Joe Arridy was talking about organizing a campaign to seek a pardon. Denver attorney David Martinez attended the ceremony and was quickly enlisted in the cause.

“That’s where I met Bob Perske,” Martinez says. “He said he talked to a lot of attorneys who said they would try to help him get a pardon for Joe, and they never called him back. I can’t help everybody, but I figured I might try to change his opinion about attorneys.”

Three years later, Martinez delivered a massive 400-page appeal for an Arridy pardon to Governor Ritter’s office, based largely on Perske’s research and official records. A former prosecutor, Ritter wasn’t known for giving executive clemency much of a workout. Perske was pessimistic.

He was sitting in his office in Darien, Connecticut, the day Martinez called to tell him the pardon had been granted – 72 years and a day after Arridy’s execution. Perske sent out e-mails to the Friends.

“We suddenly felt so happy and free, like we were at a state fair in January,” he recalls. “We learned a long time ago that if we face a tough situation like Joe’s and give up too quickly, we may miss out on a fantastic conclusion.”

Ritter issued a statement citing the “great likelihood” that Arridy was innocent of the murder of Dorothy Drain. He also noted that a 2002 U.S. Supreme Court ruling abolished the death penalty for the mentally impaired as cruel and unusual punishment – although what constitutes sufficient impairment is still a matter of debate. (The Supremes failed to intervene last month when Texas executed Marvin Wilson, an inmate with an IQ of 61.)

“Pardoning Mr. Arridy cannot undo this tragic event in Colorado history,” Ritter said. “It is in the interests of justice and simple decency, however, to restore his good name.”

The Friends of Joe Arridy added the date of the pardon to his tombstone, and an epitaph: HERE LIES AN INNOCENT MAN.