Courtesy of Denver Public Library

Audio By Carbonatix

For Mexico, Cinco de Mayo is a date. For Chicanos, it’s a metaphor. And for Denver, it’s a tradition that goes far beyond drinking margaritas and Coronas.

“We don’t do this event just in the spirit of being a drunken beer fest,” says Andrea Barela, the president of NEWSED. “You’re really there to have a cultural experience and bring your family and have a good time. Spring is here. We’re meant to get outdoors and celebrate in the heart of Denver.”

Denver’s Cinco de Mayo celebration is put on each year by NEWSED, a community development corporation that has helped west Denver residents buy homes and open businesses for over fifty years. It started the Cinco de Mayo celebration on Santa Fe Drive in La Alma Lincoln Park in 1988.

“We brought the Cinco back to Santa Fe Drive because there was no celebration really going on, a big one in the city,” recalls Andrea’s mother, Veronica Barela, the executive director of NEWSED for forty years. “It evolved out of what we were doing on the west side.”

The event has remained popular since those humble beginnings, and on Saturday, May 4, and Sunday, May 5, NEWSED will stage the 35th annual Denver Cinco de Mayo celebration at Civic Center Park. Cinco de Mayo started as a way to drive foot traffic and visibility to the Santa Fe Drive corridor,” Andrea says. “It started there and grew to be a very big event. In fact, so big we had to move it to Civic Center Park.”

NEWSED’s Cinco de Mayo celebration brings as many as 255,000 people to Civic Center over the weekend, Veronica says, but estimates from Visit Denver go as high as 400,000 – making it the largest Cinco de Mayo celebration in the country. (Veronica once saw an in-flight magazine claiming that Denver’s is the largest in the world. “I really had to laugh,” she says, knowing that the holiday is not celebrated widely in other countries.)

“NEWSED has controlled and produced it after all these years,” Andrea says. “It’s been immensely popular. It’s the largest cultural celebration in the state of Colorado. The visitors we receive are from all over the state, sometimes from other states.”

Visit Denver estimates that the average local visitor to the city’s Cinco de Mayo celebration spends $137 in Denver in one day of the festival, while overnight visitors spend $350, though it doesn’t say how much the event generates in total revenue.

Cinco de Mayo’s Origin in Mexico

Cinco de Mayo marks the 1862 victory at the Battle of Puebla, in which outnumbered Mexican forces – comprising 2,700 farmers and 2,000 soldiers – defeated 7,000 French soldiers with guns, cannons and bayonets. The French army invaded after President Benito Juárez suspended foreign debt payments in the wake of two wars, including the Mexican-American War, which ended with most of modern-day Colorado becoming U.S. territory in 1848.

The French eventually captured Mexico City in 1863; Juárez declared Cinco de Mayo a national holiday after the French left and Mexico reinstalled him as president in 1867.

A crowd gathers in Mexico City to watch a military parade on Cinco de Mayo during the dictatorship of Porfirio D

Courtesy of Mexican Government

A Juárez successor, Porfirio Díaz led a battalion from Oaxaca in the Battle of Puebla. Díaz took office and began a 35-year dictatorship until he was defeated in 1911 during the Mexican Revolution. According to Mexico’s federal archive, Cinco de Mayo “was a date that was celebrated with fervor during the Porfiriato,” which refers to Díaz’s reign from 1877 to 1911, from the dictator’s involvement in the battle to his daring escape after the French took him prisoner.

After that, Mexicans stopped celebrating the holiday that the ousted dictator had used to promote his image, and Cinco de Mayo was no longer celebrated as a national holiday in Mexico.

Today, only certain parts of the country celebrate the event, including Puebla, where the famous battle occurred. The date was never as important to Mexico as September 16, when the country won its independence from Spain, but the Mexican government still recognizes Cinco de Mayo as one of the most important events in the country’s history.

“With the exception of the celebration of September 16, the celebration of the Battle of Puebla is the most important Mexican civic holiday, as it was one of the few victories against a foreign invader,” according to the government archive. “Moreover, in the United States, May 5 is Latin Heritage Day, during which they celebrate immigration from Mexico.”

In the United States, Cinco de Mayo took on a life of its own within Mexican immigrant communities. The Columbia State Historic Park in central California claims to be the birthplace of official Cinco de Mayo celebrations, because it hosted the first recorded event on May 27, 1862.

While Díaz celebrated the anniversary of the Battle of Puebla with military parades, Mexicans living in states such as Nevada, California and Texas were celebrating Cinco de Mayo with Mexican music, dance and food, according to the Library of Congress. Honoring Cinco de Mayo in the U.S. continued into the 1930s and 1940s, even after the practice ended in Mexico.

When Americans went to fight in World War II, the U.S. brought more than 4 million Mexicans to the country to fill a mass shortage of manual labor, paving the way for the Chicano movement, which advocated for the civil rights of Mexican-Americans. Cinco de Mayo “became a major Mexican-American holiday because of Chicano activists in the 1960s,” according to the Texas Department of Education. Chicano activists began to see the victory of Mexican farmers against the larger, better-armed French army as the perfect analogy for their struggle at the time.

“The Chicano activist movement in the 1960s and ’70s used this date to inspire a community whose contribution and history had been marginalized, underrecognized and deliberately overlooked,” writes Antonio Sanchez, a researcher from Central Washington University. “Together they found a new strength, and as an underdog community adopted this day to celebrate a truly uniting sense of shared identity.”

Denver’s Early Cinco de Mayo Celebrations

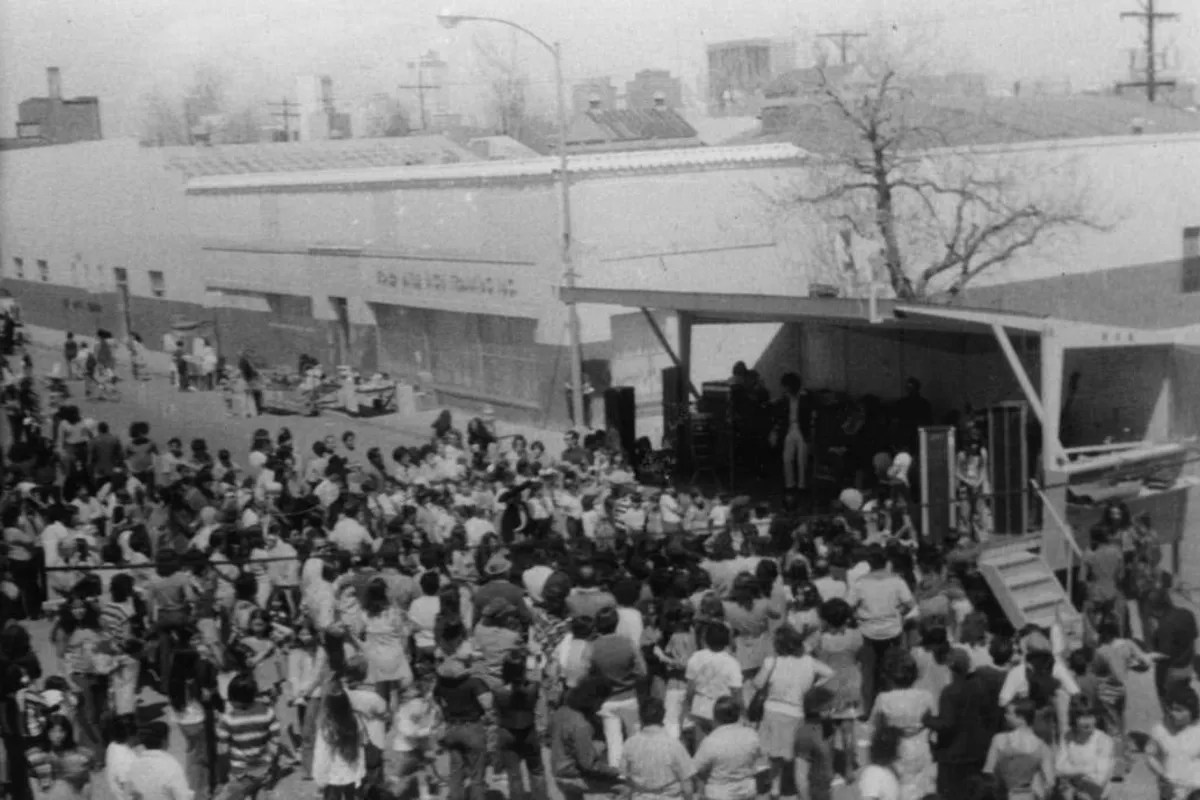

According to the City of Denver, the first Cinco de Mayo celebrations in Denver took place in the ’70s at Larimer Square and were hosted by the Chicano Humanities and Arts Council. Santa Fe Drive hosted celebrations of Cinco de Mayo as early as 1973 that were put on by the Westside Coalition, a community group that formed in response to the displacement of Latinos by the creation of the Auraria campus.

Small Cinco de Mayo celebrations were also taking place across Denver in neighborhoods like Westwood, but Veronica Barela says that those “would have just been efforts to bring out the community,” not to draw large crowds from outside the neighborhood.

In 1977, Veronica was appointed president of the New Westside Economic Development Community Development Corporation, or NEWSED (it was also a play on the term “nueva sede,” or new base).

The federal government created the Community Development Corporation, or CDC, designation in 1968 as a way of streamlining the distribution of housing and public works grants. NEWSED took on the role of a CDC for La Alma, then Lincoln Park, at a time when about 98 percent of the residents were Latino, Veronica says.

Lincoln Park was a hot spot for Chicano activism in the late ’60s, with events like the West High School blowouts and “Justice for Louie” protests after the police shot and killed Louie Pineda in 1968. However, Andrea says that NEWSED’s Cinco de Mayo event had a different tone than actions during the Chicano movement.

“Because of a lot of the Chicano activism that came out of the ’70s, those Cinco de Mayos definitely revolved around political action and bringing awareness to Latino culture,” Andrea says. “Over time, it isn’t political, but it now revolves more around the culture.”

While the Chicano movement faded in the ’80s and advertisers came in to make Cinco de Mayo about beers and tequila, NEWSED was still supporting Lincoln Park with grants to build shopping centers and offer down payment and foreclosure assistance for homebuyers.

“NEWSED’s goal was to help in a holistic approach to revitalize the La Alma Lincoln Park neighborhood,” Veronica says. “And in the early ’80s, we were really into community organizing.”

Tying to ignite interest in Santa Fe Drive as a cultural district, Veronica organized the revival of a neighborhood Cinco de Mayo celebration that would draw large crowds from outside the neighborhood.

“What’s important about having a festival when you’re revitalizing an area is it brings people to the area, so it really helped move the arts and cultural aspect of Santa Fe Drive,” Veronica says. “Santa Fe was different, because it had a high Latino population, and arts and culture were starting to bloom. It makes sense that you’d do a Cinco de Mayo and El Grito [for Mexican Independence Day] to celebrate our culture.”

NEWSED initially set up its Cinco de Mayo celebration on West 11th Avenue and Santa Fe Drive. According to Veronica, the live band, stage and 6,000 attendees were “too big to have on just one corner, so we moved it to the 7-800 block the next year.” That didn’t last long, either. “Then we had about 35,000 to 40,000 people,” she says, “so we decided to start blocking off streets.”

Pretty soon, NEWSED was blocking off every street along Santa Fe Drive from West Sixth Avenue to West 11th Avenue, and it became a two-day event. After a few years, Veronica realized that “the festival was just too big for Santa Fe Drive and that community,” she says. “It was just a huge impact.”

The Downtown Denver Partnership eventually agreed to stop holding a smaller Cinco de Mayo event downtown, opening up Civic Center Park for NEWSED in 1995. This made for a better ambience and a “much easier” setup, Veronica recalls. She credits the Cinco de Mayo celebration with spurring the development of Denver’s Art District on Santa Fe. Created in 2003, the district now hosts the largest First Friday Art Walk in Denver, which is also taking place this weekend.

In 2005, the United States declared Cinco de Mayo a national holiday with a proclamation recognizing it as “a celebration of the virtues of individual courage and patriotism of all Mexicans and Mexican-Americans.”

“Cinco de Mayo symbolizes the right of a free people to self-determination, just as Benito Juárez once said, ‘the respect of other people’s rights is peace,'” the proclamation continues.

The COVID-19 pandemic shut down the NEWSED Cinco de Mayo celebration for two years, but it returned in 2022 and continues to go strong.

“What the events are is an opportunity for us to celebrate our culture and to know us as a people. The whole event is cultural,” Veronica says. “All the food and lowriders, it’s just a great event to celebrate who we are.”

Denver’s Cinco de Mayo celebration kicks off on Saturday, May 4, with a parade before the festival begins at Civic Center Park; a lowrider show will be set up along Colfax Avenue both days. There will also be performances by regional Mexican bands and local musicians, as well as over 150 stations with goods like kettle corn, jewelry, face painting and margaritas.

Learn more about Cinco de Mayo at Civic Center Park here; see our Cinco de Mayo events and restaurant guides for other activities today.