Michael Emery Hecker

Audio By Carbonatix

On March 21, 2022, a judge dropped the second-degree-murder charges against Matthew Dolloff, the unlicensed security guard working for 9News who shot and killed Lee Keltner during dueling protests at Civic Center Park on October 10, 2020. Dolloff had claimed he fired in self-defense after Keltner, who was there for the “Patriot Muster,” directed bear spray in his face; according to the Denver District Attorney’s Office, prosecutors asked that the charges be dismissed because they could not disprove Dolloff’s claim of self-defense.

While Dolloff is off the hook, the city has taken other actions in connection with the case.

As it turned out, Dolloff did not have a license to act as a security guard in Denver – his gun permit was from Elbert County – and Isborn Security Services, which was officially Dolloff’s employer, surrendered its license to operate in Denver for at least five years. 9News had hired Dolloff as an independent contractor through Pinkerton, one of the most famous security agencies in the world; the Department of Excise and Licenses revoked its license last summer for five years, over Pinkerton’s failure to properly vet Dolloff’s credentials.

This was not the most spectacular Denver case involving Pinkerton, however. The company, which was founded in 1850, had a wild ride through the West as the Pinkerton National Detective Agency over a century ago. Here’s a brief look back:

After the death of the agency’s founder, Allan Pinkerton, in 1884, his sons divided their father’s company into Eastern and Western divisions, with corresponding offices as regional satellites. The new Denver office opened on the Tabor Grand Opera House block to counter a branch started by the rival Thiel Agency, and was to head up the emerging Western Division. Allan Pinkerton had always resisted such an expansion, for fear of losing control and allowing the chance of corruption in remote offices. Soon after his death, though, the new Denver branch confirmed the old man’s fears.

Its first superintendent was Charles A. Eames, sent from Chicago to establish the branch, which he unfortunately made in his own image. Bringing a questionable cast west with him, his favorite detectives stole clothing and jewelry from clients as well as forced their confessions to crimes the detectives themselves had committed. One of Eames’s petty rackets was peddling a Pinkerton security service to businesses that was off the books, “Pinkerton” in name only. But the worst of the office seemed to be two of the operatives he’d brought from Chicago, Doc Williams and Pat Barry. More bag men than detectives, they were hardly cowboy detective material for getting any of the ranch business the Pinkertons had imagined. Barry had served time back east for safe-blowing.

The famous detective James McParland arrived from Chicago to secretly observe the Denver Pinkerton branch in 1887. On his word, William Pinkerton himself then came to Denver and fired everyone in the office except for the cowboy detective Charlie Siringo, who was thought too new to be tainted by its corruption and was the only employee not handpicked by Eames.

From Riata and Spurs, by Charles Siringo

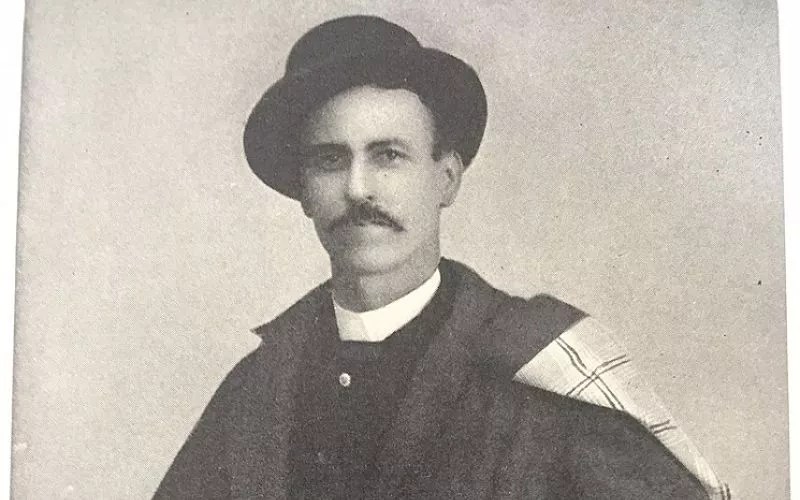

When McParland came to Denver, he was the best-known detective in America not named Pinkerton, and was formally given the superintendent position in February 1888. Reporters called him simply “the Great Detective.” A sturdily built Irishman wearing a curled mustache and round spectacles, McParland spoke with a brogue and often kept on his black bowler while working inside his dimly lit office. As head of the Western Division, he would also tour Pinkerton offices in Spokane, Seattle and Portland every few months.

McParland’s most famous case in Denver was an investigation of the murder of wealthy Rhode Island widow Josephine Barnaby, who was poisoned by an arsenic-laced bottle of whiskey sent to her while she was staying in Denver in April 1891. Her physician back home, Thomas Thatcher Graves, had recently been given her power of attorney as well as a stipend, and McParland settled on Dr. Graves as the likely killer once Pinkerton’s had been hired by the victim’s rancher son. McParland wrote a letter to the physician, inviting him to travel to Denver to testify against someone else for the killing. Dr. Graves eagerly accepted the chance to help convict another man for his crime, and McParland had him arrested for murder upon his arrival in Denver, in the first legal case of murder through the mails.

The superintendent’s job took McParland largely out of the field where he had long thrived, but he could still dispatch others down into the western mines on missions modeled, for good and bad, on McParland’s own famous work in the Pennsylvania coal fields. He had learned a fair amount about miners by living secretly among them working in a Pennsylvania coal shaft in the 1870s. The experience had nearly cost him his life, but was turned into a popular book by Allan Pinkerton, The Molly Maguires and the Detectives, which in turn inspired a stage play and became the basis for Arthur Conan Doyle’s last Sherlock Holmes novel, The Valley of Fear. McParland was hailed and hated, an agent of justice or an anti-labor murderer of fellow Irishmen. (Twenty Mollies were hanged, nine executed directly on McParland’s testimony.)

His terrifying undercover operation with the Mollies would become a template for his dark view of trade unions generally, which served him well pleasing the western mining company clients that hired the Pinkerton Agency, repeatedly inserting labor spies into unions to undermine strikes on their behalf. In December 1905, the former governor of Idaho, Frank Steunenberg, was blown up in what seemed a case of bloody reprisal for his earlier request of federal troops to contain violent striking miners. McParland helped coach the bombing suspect Harry Orchard in his testimony, linking the killing to the feared Western Federation of Miners in a larger scheme, alleging that an “inner circle” of aggrieved union leadership – Bill Haywood, George Pettibone, Charles Moyer – had directed the killing.

Next, he had the three labor leaders arrested in Colorado for conspiracy and transferred by train -kidnapped with the cooperation of legal authorities – to Boise for a trial that seized the country’s attention. Clarence Darrow put Pinkertonism itself on trial in his eleven-hour summation; when the jury found Haywood innocent, it was the shocking defeat of McParland’s long career. He died in the spring of 1919.

In the late 1930s, the Pinkerton Agency (and its rivals) suffered a reckoning from the labor espionage revelations of the La Follette Civil Liberties Committee. In 2000, Pinkerton donated an edited stash of its papers and greatest operations – 195 boxes of case files, office memos, Wild Bunch and Jesse James posters – to the Library of Congress.

Who are those guys? Butch Cassidy asks in the movie, awed by his relentless nameless pursuers.

And the Pinkertons recently added another chapter, when the agency applied to get a new security license – four years early, according to the city’s original punishment.

“They have the right to apply for a new license, since a Denver District Court judge overturned the final decision by the city to revoke their license,” says Eric Escudero, a spokesperson for Excise & Licenses. “There is no hearing required for this license to be approved. The application is reviewed, and if all qualifications are met, a license is issued. The status of this application is pending.”