Anthony Camera

Audio By Carbonatix

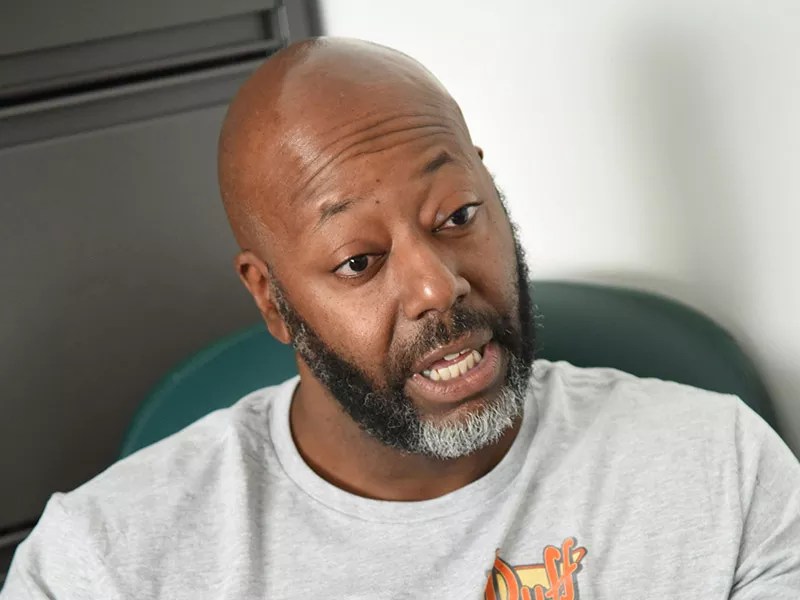

Until the day Michael Rollerson was released from prison, he’d been locked alone in a cell in the Colorado State Penitentiary for 23 hours a day. During his two years and three months in solitary confinement in the maximum-security prison, he had no one to talk to and nothing to do but watch TV and read the few books he was given. When his release date arrived, on January 6, 2008, the Department of Corrections did the same thing it does for all outgoing inmates: It gave him tan khaki pants, a blue collared shirt and a tan jacket, and put him on a bus headed for Denver County Jail, where he was officially released.

Other than the hour a day he got to roam the tiny prison yard, Rollerson hadn’t spent significant time outside in years. When his brother and sister pulled up to the jail to pick him up, he crossed the street to meet them and almost got hit by a car.

“I’ll never forget that,” Rollerson says, laughing.

His siblings drove him back to his parents’ house in Park Hill, passing through Stapleton on the way. The neighborhood was nothing but dirt and fields the last time Rollerson had seen it, but now there were apartment complexes and a Walmart. He’d never used Facebook or seen a phone with a camera on it. Many of his friends and family had died, and he’d missed their funerals. He felt like he was in a different world than the one he’d left all those years ago.

Rollerson was an eighteen-year-old Park Hill gang member when he was arrested in 2002 for a laundry list of charges: drug possession, manufacturing, dealing, theft, vehicular assault. He got sentenced to a halfway house. When he ran, he caught another set of charges, which landed him in prison.

“I was a hardhead,” says Rollerson, who is now 36. “I wouldn’t listen. I got a whole bunch of write-ups and got into a fight with a DOC correctional officer,” which landed him in administrative segregation.

When he got out that first time, in 2008, Rollerson says he was still “thinking young.” He didn’t know anything but life on the streets as a Blood, and he went from solitary right back to the same neighborhood he’d left, with the same people and the same lifestyle. His parole officer discovered he was still an active gang member when all hell broke loose after a high-ranking Crip was shot dead and the rival gang shot at Rollerson’s house. His P.O. offered him the chance to get out of the mess and move to another state. After Rollerson refused, he was put on intensive supervision. He moved to Aurora to try to escape the gang, but he started selling heroin again and ended up back in prison on drug charges.

He served another three years before being accepted to a halfway house. This time, he intended not to get caught up in the same life he had before. He worked jobs at Coors Field and laid concrete, but neither gig paid enough to support his family, and he was still abusing drugs. “Everything was going accordingly as far as not going to prison,” he says. “But my life was in shambles.”

That caught up to him in 2013, just a few months after he completed his parole. He was driving down Quebec, and out of nowhere a cop came up behind him (he later figured out he was wanted for questioning in a bank robbery case he knew nothing about). He didn’t have a license or registration and had a handgun on the front seat. So he stepped on the gas.

He thought he could outrun the police – he had before. But this time, he crashed into a bus stop and then bit the cop who pulled up next to him down to the bone. He got three more years in prison, for driving without a license, the gun, and second-degree assault on an officer.

While he was in Rifle Correctional Center, a man named Hassan Latif came in to give a presentation. Latif, who had spent eighteen years in prison himself, ran a program called Second Chance Center. Rollerson had known Latif before – he was the counselor in a program Rollerson had used to help find employment when he was out. Back then, Rollerson says, “I would come in, meet with him, get a résumé taken care of, and give him a long list of excuses of why I wasn’t doing what I was supposed to be doing.”

During Latif’s prison visit, Rollerson told him he was serious about staying out of trouble and getting back to his family. The 32-year-old had seven felonies on his record and didn’t think he would have another chance to turn his life around if he went back to prison again.

The day after Rollerson was released, he found himself in front of a modest building just off Colfax Avenue in Aurora with a sign out front that read, “Second Chance Center: Helping Formerly Incarcerated People Transition to Lives of Success and Fulfillment.”

Latif started Second Chance Center in 2012 out of his car. He ran the nonprofit on a shoestring budget composed of what he had left over from three jobs he was working, and not much else except for a trunk full of old clothes and boots and copies of a book he had written, Never Going Back: 7 Steps to Staying Out of Prison.

In just seven years, Second Chance Center has gone from a service provider run out of Latif’s car to the largest community-based re-entry organization in Colorado. It now has a staff of twenty and helps around 1,300 people every month, many of whom are on parole or under intensive supervision or are serving the end of their sentences in halfway houses. Second Chance Center isn’t just an employment service, or a mentorship group, or a social services provider; it does all that and more. The recidivism rate for its clients has been under 10 percent for the past few years, while the state and national averages hover around 50 percent.

National organizations such as the Urban Institute and the Public Welfare Foundation have touted Second Chance Center, and the state grant program that partially funds it, as a model for the rest of the country to follow. Against the odds, Second Chance has gained both the respect of the establishment and the trust of the community. Latif and his staff cite one simple reason that they’ve been so successful at the difficult job of helping people navigate life after prison: Most of them have done it themselves.

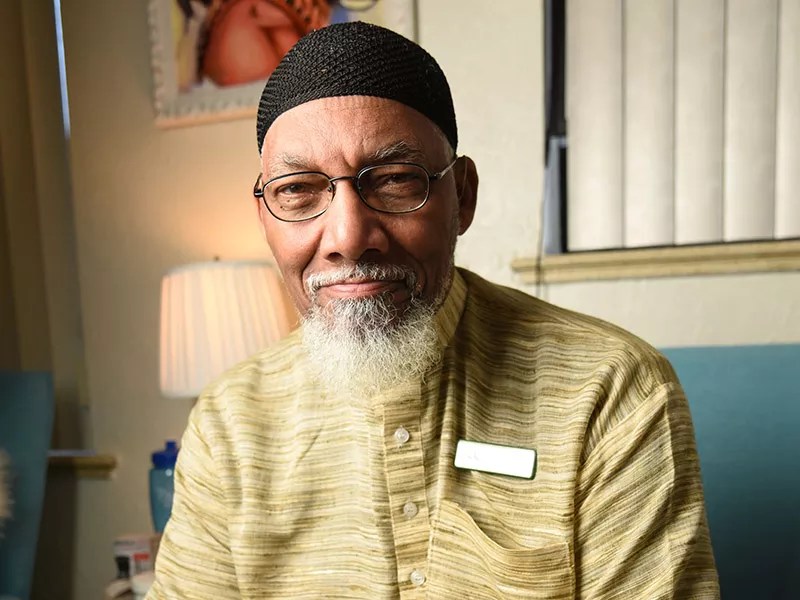

Latif grew up in Brooklyn and witnessed a lot of violence at home. For almost as long as he could remember, he had been using cocaine. “I never considered myself an addict. I just thought I used when I wanted, stopped when I wanted, started when I wanted. But the fact of the matter is, I was addicted very early, and actually it was a series of relapses that I never acknowledged,” he says.

Deputy Executive Director Sean Taylor met Latif when they were cellmates at the Limon Correctional Facility.

Anthony Camera

At age 21, he was convicted of manslaughter in New York: “I was doing a drug deal, a person attempted to rob me, I resisted, we fought, and he didn’t survive.” He did three years in some of the state’s worst prisons. When he got out, he went back to what he knew: using and dealing. Even when he moved to Colorado at the behest of friends, he couldn’t escape his own addiction.

He says he was a different person back then, one he doesn’t recognize now. “That person was someone who was quick to resort to violence for conflict resolution, a person who didn’t really respect the sanctity of other peoples’ property or even their health and well-being. It was someone who justified everything that he did,” he says.

“Sometimes the most dysfunctional behavior is the thing that people are most familiar with,” he continues. “In a desperate space, in a frustrated space, in a fearful space, people revert to the thing that they’re most comfortable with, even if it’s never served them well except to help them survive.”

Latif was soon convicted of armed robbery, and subsequently served almost eighteen years in the Colorado Department of Corrections. At first, he says, he spent all his energy and time in prison fighting to get out, appealing multiple charges in various jurisdictions. He had good reason to long for freedom: When he was arrested, he had a wife and a daughter who was not yet a year old. He watched her take her first steps in the Arapahoe County Jail, and watched from visiting rooms as she and his stepson grew up.

Fifteen years into Latif’s sentence, he started focusing on what he would do after he got out. After his release, in 2006, he entered addiction treatment at a recovery program run by the University of Colorado, where he stayed for over a year until moving in with his wife. Starting a nonprofit wasn’t anywhere on his mind. His goals were basic: stay sober, don’t commit “anything that resembled a crime,” and work hard.

But a few years later, he himself became certified in addiction counseling. Latif became a case manager at a re-entry program focused on helping former offenders find and keep jobs.

He says he was committed to the work but had issues with the program’s structure. “The recidivism rate [of the program] was about 50 percent. The DOC seemed to expect it, and the people that I worked for seemed to expect it,” Latif says.

Often, clients would have stable, well-paying jobs but would still catch another charge, blaming it on an external circumstance, and end up back in prison. Latif felt the program should do more – for example, focus more on mentorship to help clients raise their own expectations of themselves, and recognize that substance abuse and mental health were huge components of clients’ problems.

“The success part is what I was able to see there because it was about checking boxes – this person has a job, this person has a place,” he says. “But the fulfillment piece is what I thought was not being addressed. Because all those things could be in place, and there’s still some emptiness in the person; there’s something that’s not quite right. And it doesn’t matter – they’re not gonna maintain whatever progress they’re making.”

He kept trying to work up the courage to talk to the program directors about his ideas for doing things differently. But in late 2011, the program shut down.

“I was at the place in my life where I asked myself, ‘Well, what does this really mean?,’ as opposed to assuming it was all bad,” Latif remembers.

He decided to take matters into his own hands, driving his red 2002 Jaguar around looking for people who might need his help. “If I saw somebody at the bus stop, for instance, wearing khaki pants, a khaki jacket and plastic sneakers, I knew where they were coming from, so it was pretty easy to pull over and talk to that individual,” Latif explains. “More importantly, I started begging my way into halfway houses and asking to do substance-abuse support groups. … That’s where I really got a chance to sit down and talk to folks about what it was I thought they needed to be thinking about and preparing for.”

When the newly founded Second Chance Center got its first grant, which came from the federal government, Latif knew he wanted to bring on people who were as committed to the work as he was, who wouldn’t see it merely as a job. He thought of two right away: Sean Taylor and Adam Abdullah.

Taylor was only seventeen when he was convicted of first-degree murder after being involved in a gang-related shooting. He turned himself in to police the day after. Despite having no prior record, he was tried as an adult and sentenced to life in prison. He was ineligible for parole until 2029, when he would have been 57 years old.

Adam Abdullah is the center’s mentoring coordinator.

Anthony Camera

In 1992, Latif was transferred to the Limon Correctional Facility, where he met then-teenager Taylor. “He was the first, and the only person since, that I ever met in prison who was devastated by his crime and not the fact that he had a life sentence,” Latif says. “I came to know him through that lens – and the struggle that I saw him going through to try to separate himself from past affiliates and associations and choose a path that was entirely different from that.”

Latif, meanwhile, became his cell block’s spiritual leader. He had a striking quality that Taylor hadn’t found in any of the men he knew growing up: discipline. “He was teaching us a very disciplined way of life. He actually taught us how to read and speak Arabic. Like, who was doing that?” Taylor remembers.

Taylor’s exemplary record in prison served him well. In 2011, after completing 22 years of his sentence, his was one of the four first cases to be reviewed by then-governor Bill Ritter’s juvenile clemency board. Ritter commuted his sentence, moving his parole eligibility date up by eighteen years.

After Taylor was released, he made his way to the re-entry program where Latif was working. By then, Latif had already connected with Abdullah, who had just finished a 33-year sentence when he walked into the office.

“I thought it might be a little difficult to find work for [Abdullah],” Latif remembers. “He was about 65, and he had a white beard. And so on a lunch break, I stepped over and I was like, ‘So, brother, what kind of work are you looking for?’ And he says, ‘I’m not looking for a job, brother. I just finished working 33 years and three months for the federal government.’

“[He] showed me a stack of certificates that he achieved. It was about an inch and a half of certificates including two associate’s degrees, and I thought to myself, ‘That’s a terrible waste of training and education.'”

Together they helped move Second Chance Center from Latif’s car into a tiny office building on Lima Street. They called themselves the “Founding Fathers” of Second Chance Center: three black men who had collectively done 75 years of time.

“Understandably, people were looking at us pretty closely and wondering, ‘What are those guys up to?'” Latif says, laughing.

The United States incarcerates people at a higher rate than any country in the world. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, over 2 million people – nearly 1 percent of the adult population – at any given time are locked up in county jails, state and territorial prisons, federal prisons, immigrant detention centers and juvenile halls, or are involuntarily committed to hospitals.

As Dr. Jeffrey Lin, a sociologist and criminologist at the University of Denver, puts it, “This country has been an experiment in mass incarceration.” The experiment took off in the 1980s, when promising to be “tough on crime” in thinly veiled racist rhetoric became a virtual requirement for politicians getting into office.

Nearly every element of the justice system and corrections system became more punitive and less rehabilitative. The federal government and states implemented harsh mandatory-minimum sentences and three-strikes rules and poured billions of dollars into expanding police forces and constructing new prisons. The state and federal prison population ballooned sevenfold between 1970 and 2010, absorbing a disproportionately high number of African-Americans, poor people, and people with mental health issues and substance-abuse disorders.

Meanwhile, federal and state governments put little money and resources toward helping ex-prisoners transition back into society – even though over 90 percent eventually do get released. States changed parole structures so that a prisoner’s release date was tied more closely to the perceived gravity of the crime they committed, not how much change they showed while in prison – reducing incentives for good conduct, Lin says. And because more people had entered the system, more were released. Parole officers faced massive caseloads, and parolees were often released with loose or no plans for housing, employment and staying out of criminal activity.

Underfunded parole systems had neither the resources nor the political will to provide services that would help stabilize and rehabilitate released prisoners, so instead they turned to the private sector to provide increased monitoring. Today, for-profit companies contract with the government to provide everything from urinalysis to polygraph testing to ankle monitors to the halfway houses where many prisoners finish out their sentences.

Lin gives the example of polygraph tests, which parole offices in Colorado use as a monitoring tool for released sex offenders, despite that the fact that the test are notoriously unreliable. If a sex offender fails one, they have to take another. The polygraph company makes $250 off of every test. “What I’m concerned about [is that] these companies, who are giving the questions, running the exam and evaluating truthfulness, have a direct financial incentive to fail this person,” Lin says.

Similarly, many recently released prisoners are transferred to privately owned halfway houses that have direct financial incentive to cut overhead costs and provide minimal services.

In Colorado and elsewhere, bipartisan consensus is building that mass incarceration has failed as a policy. Dean Williams, the new director of the state’s Department of Corrections, has repeatedly stated that reducing the prison population by focusing on successful re-entry is his top priority. The state is well poised to lead the way in rethinking re-entry from a community perspective. But it wasn’t easy to get here.

In March 2013, Colorado’s corrections system was rocked when its executive director, Tom Clements, was shot dead at the front door of his home by Evan Ebel, a parolee who had spent much of his time in prison in solitary confinement.

Despite the fact that Clements himself had been a reformer who, as then-governor John Hickenlooper remembered at his funeral, believed “at the core of his person that anyone could be redeemed,” the reaction to his murder created a wave of fear surrounding those recently released from prison.

In response to the assassination and under intense public scrutiny, the DOC fired its parole director, Tim Hand, and revamped its parole policies. It formed a fugitive-apprehension unit to respond to ankle-monitor tampering alerts and hired more parole officers to reduce caseloads and reach prisons to help incarcerated people plan for their release.

According to Lin, there was another, informal change to parole: Parole offices became more conservative, issuing more technical violations that sent people back to prison. The state prison population, which had been declining since its peak in 2009, stagnated in 2013.

Christie Donner, executive director of the Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition (CCJRC), worked against the narrative that the best way to keep the public safe was to send more people back to prison. When Hickenlooper announced in late 2013 that he would grant $10 million to prison re-entry efforts, Donner saw an opportunity.

The money was originally supposed to be used for “more equipment, more parole officers, more case managers, all inside the facility,” Donner says. But she and other reform advocates persuaded the legislature that this was an opportunity to try something different. Their suggestion: Put some of the money toward grassroots community organizations that are already doing the work to help people transition successfully from prison into society and leave their criminal pasts behind – toward people like Latif, eight years out of prison, distributing books and old jeans from the trunk of his car.

HB-1355 passed with bipartisan support, and Hickenlooper signed the Work and Gain Employment and Education Skills (WAGEES) program into law. The Latino Coalition for Community Leadership was selected as an “intermediary” to manage the grant program, and Second Chance Center was one of the first four organizations selected for funding.

In 2018, the Urban Institute published a report on the WAGEES program, advocating its replication in other states. Key to its success, it said, is that organizations are truly “community-based.” Explains Donner: “One of the critiques of the nonprofit sector is the creation of some of these organizations that parachute into a community because they want to save somebody. We’re not down with that; that’s not what we’re talking about.”

The most successful organizations, like Second Chance Center, are led by people with direct experience, who live, work and worship in the communities they serve. They’re the ones who have the credibility to both empathize with formerly inmates and hold them accountable.

The WAGEES program now distributes about $6.7 million to programs in eighteen different locations across Colorado. The Latino Coalition, according to Richard Morales, its deputy executive director, helps grassroots organizations become sophisticated, professional nonprofits, providing an infrastructural framework so the organizations can focus on doing the work.

Second Chance Center, Morales says, has “gone out of their way in terms of creating a community. A lot of people who come out [of prison] have burned their bridges. They give them this healthy, pro-social place to belong.”

Director of Operations Dana Jenkins jokes that she had the same job in prison as she does now: She runs everything.

Anthony Camera

Second Chance Center’s budget has nearly doubled in the past year, while its founder continues to accumulate accolades and leadership positions. Latif serves on the board of the CCJRC, was appointed co-chair of the committee advising Denver on how to reform its community corrections system, and in October was appointed to Governor Jared Polis’s clemency board, becoming one of only a handful of formerly incarcerated people in the nation to serve on a committee that reviews applications seeking reprieves, commutations and pardons. He also received the Bonfils Stanton Foundation’s prestigious Livingston Fellowship, which provides professional development and grants to nonprofit leaders. He’s been asked by numerous out-of-state organizations to give talks and workshops about Second Chance Center’s work.

The center literally grew from the ground up: Clients and staff put in most of the labor to renovate the building they occupy off Colfax, which has few bells and whistles but all the necessities.

The building was “trashed” when Second Chance purchased it in 2015, says Dana Jenkins, the center’s director of operations. Now it’s her pride and joy. Clients put in the floors and painted the walls; one even installed the plumbing for a washer and dryer.

Jenkins, who spent twenty years in state and federal prisons on drug-related charges from when she was a teenager, found Second Chance Center three years after being released, just when she was on the verge of breaking down. “Everything was going great in my life,” Jenkins says. “I had a brand-new car, I had a really nice condo in the Tech Center, I had a really great job. But I was miserable.” She missed her life in prison. “I missed how busy I was. I worked from six o’clock in the morning to ten o’clock at night. I missed my family, which was the women that I was incarcerated with. I missed looking at somebody and they know what I’m feeling right now.”

That changed when she met Latif, and he eventually offered her a job. Now, she jokes that she “had the same job in prison as I do now: I ran everything.” Jenkins found almost all of the center’s furniture secondhand, or persuaded other organizations and businesses to donate it. She won a trailer in an online auction for $1,800 that now serves as a giant closet for secondhand clothes.

And then there’s the food. Jenkins says that between the two buildings and her home’s garage, Second Chance Center has 26 fridges and freezers. A chef cobbles together creative meals from donations to feed sixty to eighty people per day, breakfast and lunch.

“How can you go to a job interview, or how can you go to work, if you can’t think because you’re hungry?” Jenkins says. “Let’s make sure they eat.”

When new clients come into Second Chance Center, they are placed with what is called a care manager, not a case manager. “Our people have been cases most of their lives,” Jenkins explains.

Unlike many halfway houses, parole divisions and rehabilitation programs, there are no strict steps that a client must progress through to access higher rights and privileges and then “graduate.” Second Chance Center provides services to people on an as-needed – or even as-wanted – basis. It serves clients through several formal programs, including a weekly mentorship program based on Latif’s book; several art therapy programs; employment preparation and job placement; and one-on-one mentoring, counseling and support groups.

On an average bustling morning, clients come in for meetings with their care managers; others come to use computers to research jobs or connect with family and friends on Facebook. Still others come in looking for clothes, boots or just inspiration.

Freddy Longworth grew up as a ward of the state, in and out of foster homes and caught up in the juvenile justice system. He was convicted on drug-related charges that landed him in prison for six years. It wasn’t until 2018 that he was free – no parole, no probation, no state commitment or surveillance – essentially for the first time in his life.

It was a difficult adjustment. The first time he walked into Second Chance Center, about a year ago, he was still using meth, high out of his mind. “I didn’t really understand this place,” he says. “I just came here to get things.” Food, clothes, a bus ticket, whatever it may be.

“They didn’t judge me, they didn’t turn me away,” he says. “They opened their arms to me and they loved me.”

At the same time, they expected better of him. “They’re no-nonsense. They don’t put up with the bullshit,” Longworth says. “You come here to change your life.”

That initial acceptance motivated Longworth to start going to NA, AA and Second Chance Center every day. He’s now involved with Work Options for Women, which provides culinary training to Second Chance clients via an on-site mobile unit, and he volunteers to help at the center in whatever way he can.

Freddy Longworth says Second Chance “saved my life completely.”

Anthony Camera

Second Chance tries to help people build careers that match their interests. “If you were a drug dealer, you’re good at organizing people. If you were something else – use those skills, the tangible skills you got in whatever criminal activity you were [doing] and just flip it,” Jenkins says.

According to Latif, one of the most pressing challenges is finding homes for people with felonies on their records in the midst of an affordable-housing crunch. So he initiated a new project: a fifty-unit affordable-housing project in Aurora, Providence at the Heights, which will prioritize tenants who are chronically homeless, including those with substance-abuse disorders, mental illnesses, physical disabilities and criminal records. The project, funded largely by $10 million in low-income housing tax credits and developed by Blueline Development, Inc., is expected to be completed in February 2020. Second Chance will staff the building and offer supportive services.

The center itself isn’t free from conflict or hardships – but despite packing former members of dueling gangs into a small building every day, it has a low level of police calls and has not had any violent incidents on the property within at least the past year, according to Tony Camacho, a spokesperson for the Aurora Police Department.

“That whole provider/recipient power dynamic – we reject that at Second Chance Center. We partner with our people,” Latif says. Because 60 percent of its staff have been incarcerated themselves, “we just happen to be maybe a few steps ahead of the people that we’re serving.

“We take advantage of the common thread we have with many clients. At the same time, we’re trying to expand their perception of who can be friends to them,” he adds. One of the biggest lies we dispel is that nobody cares. This is the shit that people have heard and they’ve been telling themselves for years: ‘Nobody don’t care about me.’ Well, the fact that the community has come en masse to support the efforts of Second Chance Center is proof to our people that that’s a lie. People do care.”

As Donner puts it, Latif “draws from a deep well.” After decades of gang activity, addiction, crime and imprisonment, he has become a source of inspiration for hundreds of others who have gone through similar experiences.

“There is a depth that is developed in human beings when we traverse that journey,” she continues. “You come out on the other side, hopefully, with a lot of wisdom and resilience.”

Rollerson has been with Second Chance Center for over two years. He’s exceeded even his own expectations of himself. When he first got out of prison, he thought the only stable income he’d be able to get was disability, but he’d earned his GED and had taken some college courses in prison, and Latif expected more of him.

Through his parole officer, Rollerson connected with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 111, an electrical workers’ union that told him he could get hired as a groundman if he got a driver’s license. Second Chance helped Rollerson get a job as a traffic flagger, helped him find the clothes and tools he needed for his job, and helped him get OSHA certification and his CDL so he could qualify for a promotion. Most of all, Second Chance believed in him. “They gave me a lot of hope and a lot of wisdom,” he says. “They knew I was gonna make it.”

Rollerson is now an electrical lineman. He loves his job and is able to support his family. This past year, he testified before the state legislature in favor of the “ban the box” bill, which prohibits employers from inquiring into an applicant’s criminal history on initial job applications.

Second Chance Center is still a part of his life – Latif and other staff members call from time to time, just to check in. “Walking into here, I get the same love that I got the very first day ’til now, and I see the same struggles that I went through,” Rollerson says.

For those who have been caught up in the wheels of the criminal justice system for their entire lives, there is plenty they can blame, much of it fairly: the absurdity of mass incarceration, the dismal conditions of prison and halfway houses, the racism that predisposes black people to more frequent arrests and longer sentences. While Latif acknowledges all of that, he focuses on helping his clients accept responsibility for the role they have played. After all, he says, that’s what helped him confront his past and move on.

“I needed to do the kind of things where I knew what I was responsible for, as much as that’s possible. And I wanted to commit to the kind of things I could feel good about, that I wouldn’t have to hide from,” he says.

That commitment gave Latif an insight any client of Second Chance Center can recognize: “I actually am making the world a much better place, and not because of my involvement with Second Chance Center, but the fact that I’m not fucking it up anymore,” he says. “I’m not harming anyone, no one has the need to legitimately fear me. I’m not taking anything from anyone, I’m not putting any new negative thing into the community. So whether people know it or not, my abstinence from those kinds of activities makes the world a better place. That might be a far reach for some, but it’s the reality.”

Rollerson feels that, too. “I’m living life for real now,” he says.