The Triangle/Westword Photo Illustration

Audio By Carbonatix

On Sunday, October 8, the Triangle closed its doors – again – in the middle of its golden-anniversary year.

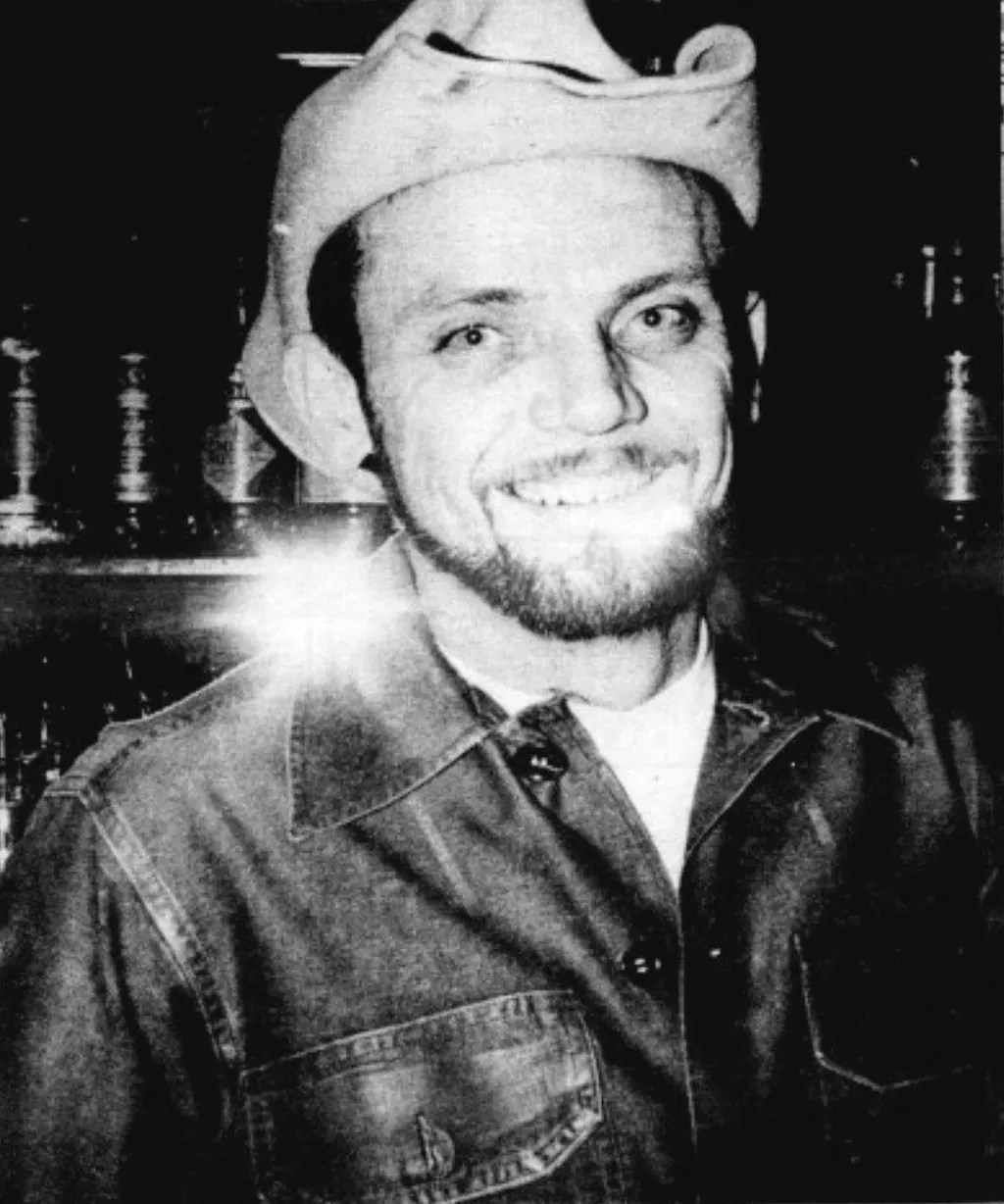

The original Triangle was the brainchild of Denver native and Vietnam veteran Donald Walter Young, a Marine sergeant and decorated tank commander. After leaving the service in his early twenties, Young returned to Denver and plunged into the gay-bar business.

He got started by renting small back rooms in two downtown gay bars – the Tic-Toc, at 1512 Broadway, and My Place, at 1540 Welton Street – according to 85-year-old Bill Olson, an early patron who now lives in Guadalajara and meticulously collects and catalogues gay history trivia. In those repressive times, gay bars often had discreetly marked alley entrances so that patrons could come and go without being seen; only those in the know would find their way.

Young’s first establishment featured an alley entrance, and he named it Don’s Alley. His customer niche was the hyper-masculine leather and denim crowd. “The leather crowd followed him wherever he went because he was the only game in town for men into leather and Levi,” recalls Olson.

Don Young, who founded the Triangle in 1973, on the cover of Out Front in 1983.

Colorado Historic Newspapers

In early 1973, Young bought a fifty-year-old, two-tone brick building at 2036 Broadway that had once housed light industry, and transformed it into the Triangle Lounge. That summer, a fire of suspicious origin damaged the property. But by December, Young had remodeled it, and the Triangle reopened for business. With great fanfare, Young held a grand-opening celebration in early March 1974. In subsequent years, he celebrated the bar’s anniversary on the first weekend of March with a three-day blowout featuring lavish buffets graced with ice sculptures and cocktail shrimp. On its eleventh anniversary, in 1984, the gay publication Out Front‘s congratulatory article on its earliest and most valued advertiser reported that the Triangle had been open longer than any other Denver gay bar then in existence.

Prior to the mid-1970s, gay Denver was deeply closeted. But gay bars had existed since at least 1939, according to Tom “Dr. Colorado” Noel, who wrote his master’s thesis on the history of Denver’s bars and penned a 1978 piece on gay bars for The Social Science Journal from the perspective of “a straight outsider.” Remarking on the fleeting nature of the gay-bar business, he wrote, “Within this rapidly changing bar world, probably 100 Denver bars have been predominantly gay at one time or another. This striking instability…has been one indication of the social pressures placed on gays.”

Before the Triangle, Denver’s gay-bar scene was mostly underground, held in check by the Denver Police Department vice squad, which wielded antiquated laws against lewd behavior and men in female attire, among other things. Until late 1974, same-sex kissing in public, even in a gay bar, violated the “public indecency” law. The kissers could be arrested and the bar cited – even closed, if too many violations stacked up. Police also harassed bar customers entering and leaving gay clubs by issuing jaywalking tickets and pulling over exiting late-night patrons and charging them with DUIs.

Young executed military discipline over the Triangle’s atmosphere. It was all manly all the time, and occasionally he insisted that patrons wear at least one leather item. Women were not allowed through the door, and a “no open-toe shoe” policy kept out male drag queens. Over time, a select handful of queens he approved of got a pass. While gender politics provided a philosophical basis for lesbian separatism in the ’70s and early ’80s, Young was creating a separatist male space unencumbered by gender ideology. It was a place for men who loved men and manliness to hang out together without shame.

From the beginning, Young was revered by his patrons. While he wasn’t known as an advocate for gay liberation, during an extended era of police repression, he courageously carved out a space for masculine gay men to congregate and enjoy lusty camaraderie.

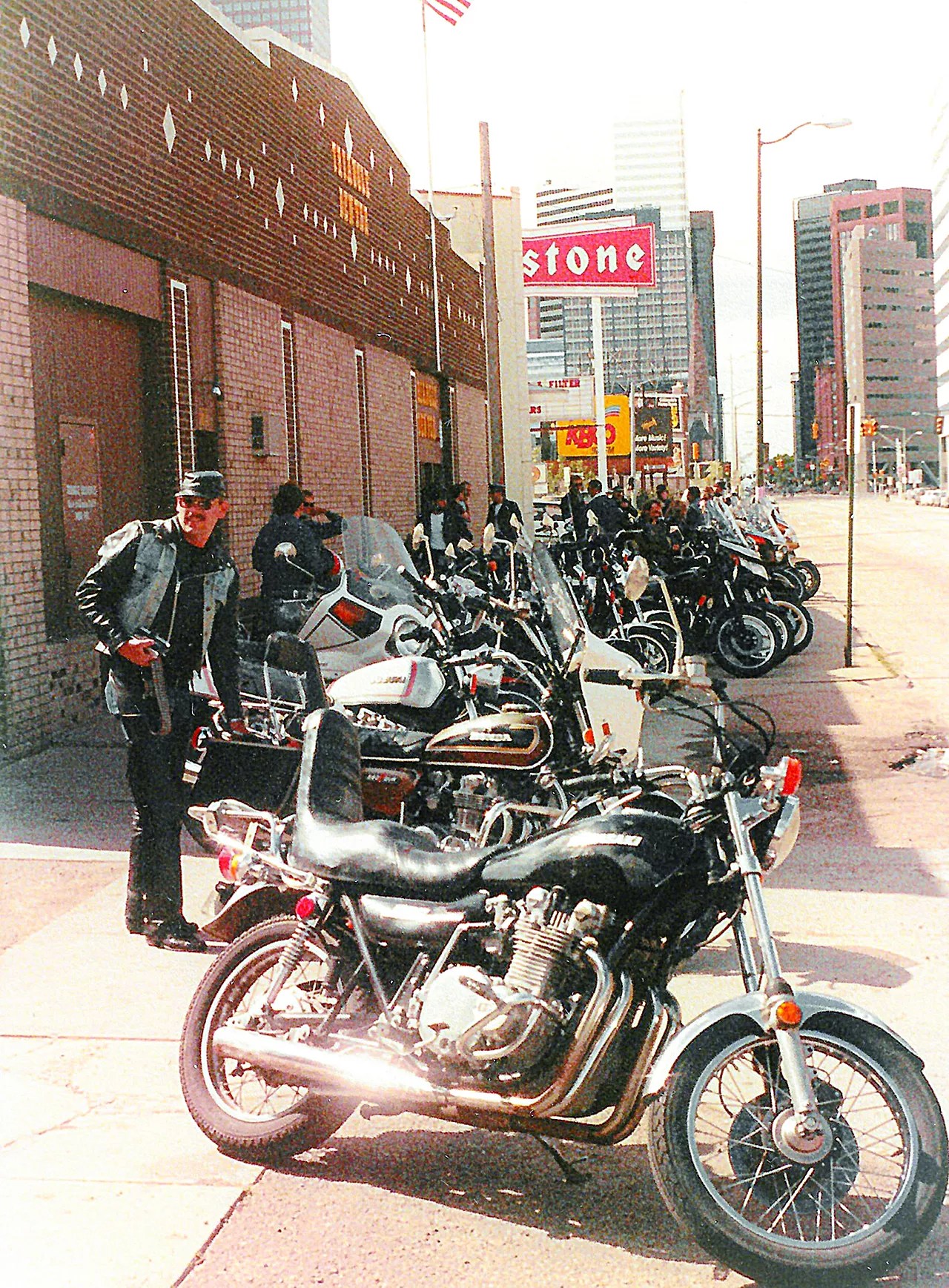

The Rocky Mountaineers Motorcycle Club were regulars at the Triangle.

Bill Olson

According to writer George Seaton, the Triangle was a “singular example to all who entered that the legacy of Stonewall was ferociously alive in Denver as a new birth of freedom for gay men – an insistence that masculinity and all its trappings were not anathema to them.” Seaton recalls some of the early Triangle’s atmospheric details: the thumpa-thumpa music, the ring-ding-ding of pinball machines, the scores of miniature American flags waving in the rafters every Fourth of July, and the many times every weekend night when Young’s amplified voice was “like shards of glass on a blackboard yelling, ‘Taxi at the door! Taxi at the door!'” And, long before smoking was outlawed in bars, “a gray-white haze lazily floated above our heads, shape-shifting with the opening and closing of the front door,” Seaton says.

Ric Durity first visited the Triangle in 1975, when he arrived from the Washington, D.C., area for graduate school at the University of Colorado Boulder. The 22-year-old was already a veteran of leather bars. “From the outset, the atmosphere at the T made it a welcoming place,” he recalls. “For many of us younger men, Don Young was recognized as a ‘leather elder.'”

At the Triangle, Durity met Gerard, a man twice his age and an influential figure in the region’s cultural scene. (Gerard is a pseudonym, because he was not out during his lifetime.) Durity and Gerard spent the next seventeen years together, until Gerard died of AIDS in 1992. “Many times I would meet people traveling to Denver to perform at the DCPA, or business, or political events,” says Durity. “They were cautious about keeping a low profile, especially during the earlier days when there was fear of a vice operation that could end their career.”

For some, the Triangle was intimidating at first. “Paul” (who requested that his real name not be used) was another CU grad student in the late ’70s, and he remembers driving down to Denver in 1977 with his then-boyfriend to check out the Triangle. “We drove around, a tad skittish, got scared and drove back to Boulder without going inside,” he says. A few years later, on Halloween 1982, Paul met his future partner at the Triangle. They spent four years together, often enjoying happy hours at the bar, until the partner’s health declined due to AIDS; he died in 1986.

Paul, a public-health worker, later visited the Triangle on a different mission – to help Young and his team comply with regulations aimed at reducing HIV transmission. Now in his early seventies, Paul is a long-term survivor of HIV.

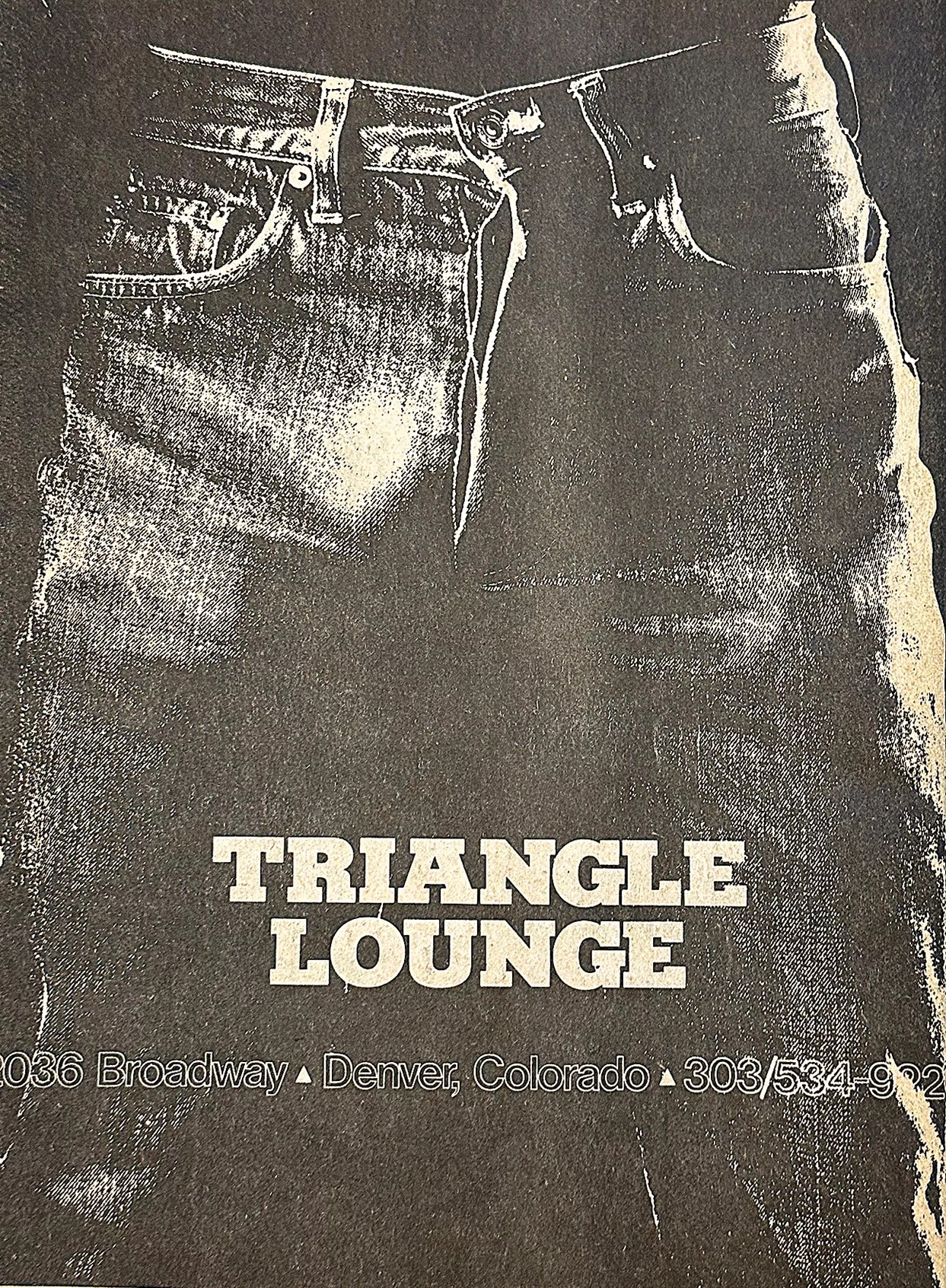

Young understood the power of advertising. He paid top dollar for the back page of the gay publications where he ran ads. For years on end, the ad was the same – a darkly lit close-up shot of a man’s crotch snugly clad in denim, with enough of a bulge to stir curiosity about what lay beneath. Usually the ad included only the bar’s logo, address and phone number, but it would occasionally announce a special event or carry a greeting targeted at Stock Show visitors or a motorcycle gathering.

The Triangle was known in gay men’s circles as one of the nation’s premier leather bars; it was on the must-do list of any leather guy traveling to Denver for work or pleasure – or simply to escape more conservative towns in the Rocky Mountain West. Durity, who now lives part-time in Southern California, says that “even today among older leather men I meet in Palm Springs, they have a strong association between Denver and the Triangle.”

Jim Kane, president of the Rocky Mountaineers Motorcycle Club, in 1970.

Courtesy of Bill Olson

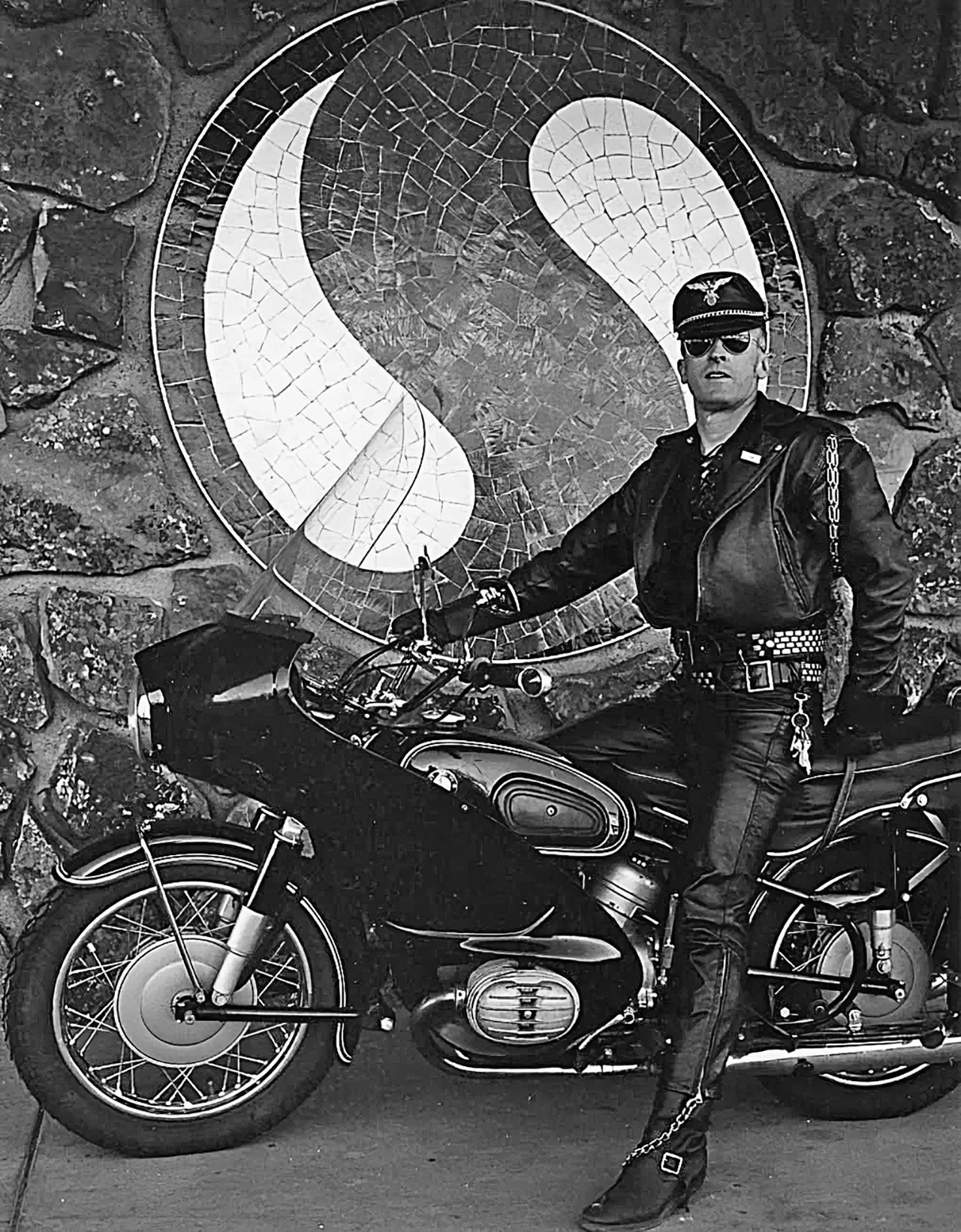

The image of the hypermasculine homosexual man was popularized by Tom of Finland in the 1970s, and it was this aesthetic that inspired the looks you could find at the Triangle. Every Saturday night, you’d see the same Village People archetypes: the black-leather-clad biker, the construction worker in the too-tight T-shirt, the plaid-flanneled lumberjack (no Indian chief, however). You could fantasize about hooking up with a horny long-distance trucker in his eighteen-wheeler parked nearby, and you’d find yourself with a shoe salesman who lived in Arvada. You’d imagine a quick and dirty romance with a muscular, greasy-haired mechanic and end up with a buttoned-down state bureaucrat. And that cowpoke in the skin-tight Levi’s smoking Marlboros? A piano teacher from Des Moines.

The Triangle was a socially flattened space where patrons projected some variation of a blue-collar persona. All the guys were average Joes out to get a little snockered and, if lucky, laid. It was a democratic space where the bankers rubbed elbows with the bakers, the lawyers cruised the grocery clerks, the prison guards propositioned the trust-funders.

In the 1970s and ’80s, if you were at the Triangle on a weekend night, you were probably looking for sex – and for many, not just sex, but a specific kind of sex. If you were a leather/Levi top (the dominant or insertive role), you would dangle a keychain from the left side of your jeans; if you were a bottom (the passive or receptive role), your keychain hung on the right.

For those with more finely tuned sexual tastes, there was the hanky code. You’d stuff a dark blue hanky in your left pocket to display your desire to play the top role in anal sex. Wearing a light-blue hanky in your right pocket meant you were looking to perform oral sex. Gray was for bondage, black for S&M, yellow for water sports, orange for “anything goes.” Some guys sported multiple hankies, some changed hankies depending on their mood. Men using the hanky code didn’t beat around the bush. There was no need for the awkward and clichéd “What are you into?” query. What you were into was your fashion statement.

While the early Triangle wasn’t a sex club or a back room, a few patrons sometimes got carried away…particularly in the basement bar. The Triangle was shuttered many times over the years, sometimes several times in the same year, for “lewd and lascivious” violations witnessed by plain-clothes vice officers. The gay grapevine worked well to alert patrons when cops had closed the Triangle, and when it reopened. According to one source, the Triangle’s file at the Denver Department of Excise & Licenses was stuffed full of violations.

If Young or his bartenders knew Vice was in the bar, they signaled patrons. Seaton was at the Triangle one night when the cops came in. “The lights popped on, and there was complete silence for a moment, and the cops circulated through the bar. I don’t remember anyone being arrested,” he says.

Sometimes it was more dramatic. According to an account of an August 1, 1976, raid, Denver police entered the busy bar to determine whether the number of patrons exceeded fire-code capacity. Young came on the loudspeaker and ordered patrons to leave by any of three exits, and to resist the police. Then he played “God Bless America” full blast. The cops arrested Young for interference.

Young was arrested again during a September 1982 raid for refusing to allow police officers to inspect the bar for liquor-code compliance. Some patrons were also arrested after being observed engaging in anal sex and masturbation.

Ironically, given the Triangle’s reputation for promiscuity, all but one of the half-dozen former regulars I interviewed – all over the age of seventy – had found a long-term partner at the Triangle. All but one had also lost a long-term partner to AIDS.

While AIDS appeared first among gay men on the coasts, its arrival in Denver wasn’t far behind. In pre-internet years, gay men who traveled packed the Damron Guide, “the little black book of gay travel,” with hundreds of listings and ads for gay establishments across North America. Because many gay men incorporated sex-hunting into their travel itineraries, the yet-unknown, undetectable and unnamed virus quickly spread from city to city through gay bars and bathhouses.

The profound impact that AIDS had on the leather community can’t be overstated. In 1982, a year into the AIDS epidemic, Young closed the Triangle’s basement soon after science confirmed that the disease – first called Gay-Related Immune Deficiency (GRID) – was sexually transmitted. For many gay men, it was too late; by then, they were already infected with HIV, and some were getting sick. Gay bars and bathhouses realized that their survival depended on cooperation with public-health authorities to encourage prevention.

After more than a decade of post-Stonewall sexual liberation, many gay men reluctantly but abruptly adopted “safe-sex” guidelines. Others had a harder time downshifting, believing the threat would soon blow over. No one could have guessed that thirteen years would pass before there was a treatment that would begin saving lives. Ronald Reagan’s America didn’t give a shit.

The infamous Out Front ad.

Colorado Historic Newspapers

My own relationship with the Triangle was complicated. I grew up in a family of teetotalers, so going to a bar, or even knowing anyone who did, was not part of my upbringing. I began drinking in college, but didn’t frequent bars much because I couldn’t afford to. My first gay bar was the Flame in Ann Arbor, where I came out after quitting grad school at the University of Michigan. It was a dump, but a festive one, the only place in town where gay men could regularly find each other.

In 1976, my then-partner-now-husband Bob Janowski and I landed in Denver. We sometimes went dancing at the Broadway and the 1942, and sometimes went to beer busts at the Southtown Lumber Company (now Li’l Devils). I’d mastered the gay-bar basics, but the Triangle was like the gay-bar equivalent of graduate school. I was a preppy, happily partnered young professional already running Denver’s brand-new Gay Community Center by 1977. Part of our mission was to provide alternatives to gay bars. I had a reputation to think of, and the soupçon of sleaze that was part of the Triangle’s mystique kept me from crossing its threshold. Friends and colleagues urged me to “see and be seen” out in the community. It was part of my job to connect with other leaders, and one of them was Young, a hero in the eyes of Triangle patrons.

I don’t recall my first visit to the T. It was probably a Sunday afternoon beer bust with some friends. Eventually, I worked my way up – or down, actually – to a few late-night, last-call prowls through the body-to-body friction-fest that culminated on weekend nights. The commingled smells of smoke, beer breath and man sweat became the fragrance of lust. A time or two, I got tipsy enough to sloppy-kiss strangers, an act that could have gotten me arrested just a few years earlier.

The main floor was wild at times, but tamer than Don’s Alley, the basement bar where sexual shenanigans took place – at least until 1982. When I was at the community center, and later in the early ’80s, when I wrote for Out Front, there were times I had to talk to Young. The man intimidated me. He was gruff and manly in a blue-collar, no-nonsense way. We moved in different spheres and viewed the community through different windows. I was an activist with an idealistic vision. He was a hard-nosed businessman who sold booze for profit. I had no idea what he thought of me – or if he thought of me at all. Why would he? A lot more people were buying what he was selling than what I was pitching. We talked a few times about matters I don’t much remember – a donation to a fundraiser, a comment for a news article; the conversations were always quick and to the point. It was clear that he wasn’t someone I ever wanted to rile.

My boss, Phil Price, Out Front‘s publisher, told me about the few times he’d been on the receiving end of a pissed-off Don Young phone call.

The 1969 Stonewall uprising in New York City had unleashed a tsunami of gay activism across the nation. During the 1970s and early 1980s, the lesbian and gay movement in Denver burgeoned. (The transgender component of the movement came later.) The growth of lesbian and gay bar culture proliferated alongside political and social progress, but most bars remained relatively unengaged in community organizing, other than hosting fundraising events organized by various groups. From their perspective, there wasn’t much need to build a community, because bars were already the heart of the community. What more could you need?

A lot, as it turned out. As early as 1971, some activists were creating “alternatives to the bars.” One of the successful early groups was the Gay Coalition of Denver (GCD), founded in 1972. The GCD, which got Denver City Council to repeal several anti-gay ordinances in 1973, spearheaded various non-bar activities such as weekly coffeehouses, coming-out rap groups, political discussions and other activities away from bars. Some activists began to see the bar-centric gay life as harmful. In 1974, the GCD’s newspaper, The Rhinoceros, concluded that “the bars play an overly dominant part in gay city life” and called for “places where gays might meet without the tensions of cruising and alcohol.” Ironically, the GCD depended on gay bars to disseminate fliers attracting people to its activities.

Excessive drinking helped many gays and lesbians drown shame, loosen inhibitions and momentarily escape an internalized sense of worthlessness. If youth growing up in the post-World War II era learned anything at all about homosexuality, they knew it bore the stigma of being sick, sinful and against the law – even unpatriotic. Society’s major institutions deplored homosexuals. The 1950s Lavender Scare promulgated by Senator Joseph McCarthy and FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover led to the firing of thousands of suspected homosexuals from the federal government, including the military, based on fears that gays could be easily blackmailed by Communist spies.

In Denver, as elsewhere, local politicians, police and newspapers fretted about the “homosexual menace” and “moral rot.” As they grew into adults, younger gays and lesbians realized they’d been taught to despise the kind of person they were discovering themselves to be. The burden of leading a hidden life – except when getting wasted late at night in a gay bar- led many to addiction and its often tragic consequences. Activists believed it was time to create new ways for LGBT people to live their lives openly and without discrimination – to substitute pride for shame.

Some bar owners felt threatened by this line of thinking, some felt indifferent, and others opened their doors to groups raising money for various charities. Why not? People coming in to support a cause would also buy drinks. Often, the entertainment at a fundraising event – usually a drag show – wouldn’t get underway for an hour or more after the advertised start time so that patrons would buy more drinks while waiting.

Young wasn’t known as a major donor to lesbian and gay causes, but Olson says that he was generous in other ways – helping an employee or a customer with rent, or bailing patrons out of jail. Sunday afternoon charity beer busts were popular – and from a business perspective, a shrewd marketing tactic to attract new regulars. Young rolled out the red carpet for fraternal groups, especially the Rocky Mountaineers Motorcycle Club – for many years the oldest gay organization in Colorado, running from 1969 to 2014. The RMMC made him an honorary member. He even made an exception to his no-women policy by welcoming the short-lived lesbian motorcycle club Free Spirit in the late 1970s.

Members of the Free Spirit lesbian motorcycle club.

courtesy Bill Olson

Pressure from the Denver vice squad evaporated in 1983 with the election of pro-gay mayor Federico Peña and a mandate from his new Department of Public Safety head to back off on harassment of gay bars and their patrons. That was the good news. The bad news was that AIDS was now making major inroads into Denver’s gay male community.

Employees and loyal patrons of gay bars were among Denver’s earliest diagnosed cases. Before long, gay bars, including the Triangle, collaborated to mount fundraisers to support AIDS organizations. But there was a disconnect between how budding AIDS service organizations wanted to use charitable dollars and the expectations of many of those raising the funds. Community organizers saw the need to develop a service infrastructure for people with AIDS (PWAs) and prevention programs to stop its spread. Many of those raising funds in the bars thought money should go directly into the pockets of PWAs who were too sick to keep working or maybe needed extra cash to fly home one last time.

The AIDS epidemic wrung many Denver gay bars dry. The freewheeling years of sexual liberation morphed into a morose era of grief and loss. Many sexually active gay men settled into relationships and stayed home. Others stopped having sex altogether. Hundreds died every year, with the death count growing each year until it peaked in 1995, when effective antiviral treatments first became available.

Seaton found the love of his life at the Triangle in the nick of time; he met David Rowe in the upstairs bar. “I didn’t know it then, but my carousing days were over. I think there was something more to David’s and my meeting than just another night at the bar,” he says. “Maybe just dumb luck.” Seaton and Rowe, now retired and living in the mountains, will celebrate their 41st anniversary in November.

Things didn’t turn out as well for Olson. After flying into Stapleton Airport (just a ten-minute drive to downtown) from a trip, he headed straight for the Triangle. He kept circling the bar, glancing repeatedly at one young man who, at last call, demanded, “Well, are you going to take me home or not?” Olson replied, “Yes, I am.” A couple weeks later, Lee Bacus, a recent college grad, moved in with Olson. The couple spent 24 years together until Bacus succumbed to AIDS in January 1996 – around the time that antiviral therapies began saving lives.

Clark Thompson, who owned the Triangle from 1998 to 2005, at the 2000 Pride parade.

Phil Nash

Don Young’s Triangle collapsed thirty years ago. Since its 1973 opening, it had hosted several generations of LGBTQ patrons. For most of its first two decades, the T was strictly a men’s bar. But by 1990, the bar could no longer legally discriminate on the basis of sex in public accommodations, thanks to Denver’s newly enacted human-rights ordinance. The comprehensive ordinance had been written and passed through the lesbian and gay advocacy organization EPOC, or Equal Protection Ordinance Coalition. That giant leap in civic progress, as well as the devastation of the AIDS epidemic and ever-changing perceptions about gender and sexuality, forecast the end of an era in Denver gay history.

In the April 21, 1993, issue of Out Front, reporter Sam Gallegos revealed that Nevia, Inc., Young’s corporate holding company for the Triangle, owed $36,360.30 in back taxes. The bar was seized and everything on the premises sold at auction. Later that year, Gallegos reported that Young faced charges of check fraud for passing bad checks at King Soopers. Rumors had long circulated about Young’s drug use and poor health. “Don always looked sick,” Seaton remembers, “from the first time I saw him to the last.”

Young died in 2000 at 53, having enjoyed wide admiration and some successes, but also enduring far more than his share of hard knocks. He is buried at Fort Logan National Cemetery.

His empire had disintegrated, but the temple that housed it remained. Despite nostalgic efforts to revive it, however, the Triangle would never be the same – or even close.

A silent partner bought the business and the now-seventy-year-old building in 1993 and sold the bar operation to Clark Thompson in 1998. Thompson, a retired Navy commander originally from rural Wisconsin, had met his partner, Phil Schroeder, at the 1987 Second National March on Washington for Gay and Lesbian Rights. Soon after, he moved to Denver to be with Schroeder, who died of AIDS in 1994. Before that, the pair enjoyed patronizing the Triangle – though Thompson says he never met Young and knew little about the owners who followed in the mid-’90s.

Thompson has fond memories of his years as the Triangle’s owner, with one exception: getting his liquor license. “I had to assure the city that the basement bar was closed and would never reopen,” says Thompson. While he was considering the purchase of the bar, the previous management had hosted a leather event that reportedly involved fondling. City authorities weren’t amused. “The Triangle had been cited many times over the years,” recalls Thompson, who agreed to keep the basement shuttered. Under his ownership, which continued through 2005, the bar received zero citations.

During his years running the Triangle, Thompson added dancing and an improved outdoor seating area. He welcomed everyone at the bar, though he says that the few female patrons were usually friends of his gay male customers. The RMMC continued to hold events there, while younger regulars of the Fox Hole, which had recently closed in the Central Platte Valley, found a new home at the Triangle. “Older patrons liked it because all these younger good-looking guys were there,” Thompson recalls.

But within a few years, a new gay bar catering to a young crowd opened a few blocks south, and the Triangle’s business quickly dried up. “All good things come to an end,” says Thompson. “The gay community in Denver is much different from when I moved here in 1987. They’re a fickle group and will go from place to place.”

The writing was on the wall. Thompson sold the bar in 2005, and the new owner lasted only a year. Over the next decade, the building housed first a rock club, Rockaway Tavern, and then Würstkuche, a German-style restaurant that was a link in a national chain. Neither business lasted long.

Then a new crew of owners, which included Scott Coors – son of Bill Coors, an ultra-conservative who ran the family brewery for decades – took over, and brought back the Triangle in 2017. It was doing well in the beginning, but then the pandemic hit.

The Triangle closed “indefinitely” on October 8.

Jay Vollmar

The recent closing of the Triangle was attributed to the discomfort of people heading to the bar having to navigate homeless encampments, which had proliferated in the area. The Triangle customers of 2023 felt unsafe. In the 1970s, going to the T felt a little bit dangerous, too – a walk on the wild side. That was part of the attraction. Back then, the Triangle was on the outer edge of downtown; if you went farther north on Broadway, you were in the dark and dismal no-man’s-land of undeveloped Brighton Boulevard. There was no Ballpark neighborhood, no RiNo. And with cops zealously monitoring gay bars both inside and out, just being in the vicinity of a gay bar was unsafe.

Today, rapid development is converging on all sides of the 2000 block of Broadway. Can a 100-year-old structure at that location withstand market forces that have boosted land values skyscraper high?

Durity holds out hope that someone will find an innovative way to animate the space “for a new generation of Denverites. It would be sad to see the building meet the fate of the wrecking ball, like many other Denver landmarks.”

Longtime RMMC member Gregg Looker, whose six motorcycles were christened at the Triangle, doubts that the bar will come back. “After it was resurrected, I tried to attend the charity beer busts there, but it just wasn’t the same,” he says. “It had been taken over by gays forty years my junior.”

Nostalgia is unlikely to overcome market forces. “Realistically, that block is ripe for renovation,” says former owner Thompson. “There are no more resurrections for the Triangle.”

It may not matter. In the LGBTQIA2S+ world of ubiquitous rainbows, Grindr, proliferating pronouns, non-binary gender fluidity, and queer as both a noun and verb, is there any room for the hypermasculine gay man? The Triangle where they could strut their sexuality in at least one semi-public space without shame or guilt bore little resemblance to the Triangle that just closed.

A friend dutifully reminds me of the Triangle’s informal honor code: What happens at the T stays at the T. If so, the cracks and crevasses of the Triangle are stuffed with a half-century of unspoken memories, salty and sweet, tough and tender. For some years to come, they will drift through daydreams of the remaining men who made them.