“I opened this so people could trip with my art — my ant farms,” Lemanski explains. “That’s what I like to do. It’s so beautiful when you’re tripping with my art, and I want to get a lot of people in here experiencing that. The next step would be to get the art into people’s homes. And then, if I can prove the concept of going to a place to trip like you’d go to a bar, I can franchise it.”

That's a lofty goal for an incredibly niche concept. But if it can succeed anywhere, it will succeed in Colorado — where psilocybin, dimethyltryptamine, mescaline and psilocin were legalized after the state's voters passed Proposition 122 in November — and particularly in Denver, where trippy people like places built by trippy people. (If you've been to Meow Wolf's Convergence Station, you've seen enough moon-sized pupils to know that.)

Besides, Lemanski conceived of Ant Life after achieving another seemingly impossible goal.

“I circled the Earth on a bicycle for 999 days,” he says. “And the only thing I missed back home was this ant farm that I had made. I kept thinking about it. I wouldn’t miss showers or anything like that, but my ant farm? For that I was like, ‘I’m excited to get back.’”

Jacob Lemanski grew up in rural south-central Pennsylvania, where he rode the bus into the town of Spring Grove to go to school and was introduced to ant-keeping through classic children's kits.

He graduated from West Virginia University with an engineering degree in December 2006, and just months later moved to Colorado, where he secured his first engineering job at Wanco in Arvada. Not long after, he created his first ant farm as an adult.

Wanco "made the signs that flash how fast you are driving," Lemanski recalls. "Those signs get shot a lot and sent in for repairs. I took two pieces of plexiglass that had bullet holes in them to make the first ant habitat, then I got it framed at Michael's and stuck a lightbulb inside. I was inspired by a childhood memory of having an ant farm. I put ant eggs from outside in with the ants that were already digging, and when the eggs hatched, a war broke out. I remember being fascinated by the whole situation. It's one of my earliest memories."

He's always been curious and adventurous, and at 27, when he was an Air Comm Corporation engineer designing air conditioners for helicopters, he came up with the idea of biking around the world. His goal wasn’t to overcome any fear or get to a particular destination, but to “keep going until I stopped," he says. "I wanted to get to a place where I could go no further, and know I went as far as I could.”

After saving up $24,000, Lemanski embarked on his journey in 2013. He started in Portugal and biked across Europe into Russia, then down to Mongolia and China. He then flew to Alaska and cycled all the way down to the tip of South America before flying to Australia and biking its western coast, Tasmania and New Zealand. He took a flight to his final continent, Africa, and biked from South Africa up to Egypt. He estimates that he crossed a total of 42 countries.

Camping for most of his journey, Lemanski was able to commune with plenty of ants to allay any longing for the ant farm back home in Colorado. “I would take my cooking pot and set it next to an anthill and let the ants do my dishes every night,” he recalls with a smile. Even with ants as companions and a cleanup crew, though, life can get boring when you’re cycling every day, and that’s what led to Lemanski’s first experience with psychedelic mushrooms.

“When I was traveling down in Argentina, I would pick mushrooms off the cow patties,” he says. “I knew that psilocybin mushrooms grow on cow patties. So I tasted a little and went to sleep, and when I woke up the next morning, I was like, ‘I probably shouldn’t do this.’

“I put them in my little trash bag and biked a couple miles, and then I was like, ‘I’m gonna eat them all,’” he remembers, and laughs. “And then I was on the hunt every night looking for my cow-patty mushrooms.”

After three years of biking, Lemanski returned to Colorado in 2016. Three months after his homecoming, he was reflecting on his journey when his then-roommate in Boulder invited him on a different sort of trip. He offered Lemanski a hit of LSD, on blotter paper printed with — what else? — an ant. “An antacid,” Lemanski quips.

It was his first time taking acid — a far cry from cow-patty boomers — and he rode out the trip by looking at his ant farm for ten hours.

“And that night,” Lemanski says, “I conceived to build the world’s most beautiful ant farm.”

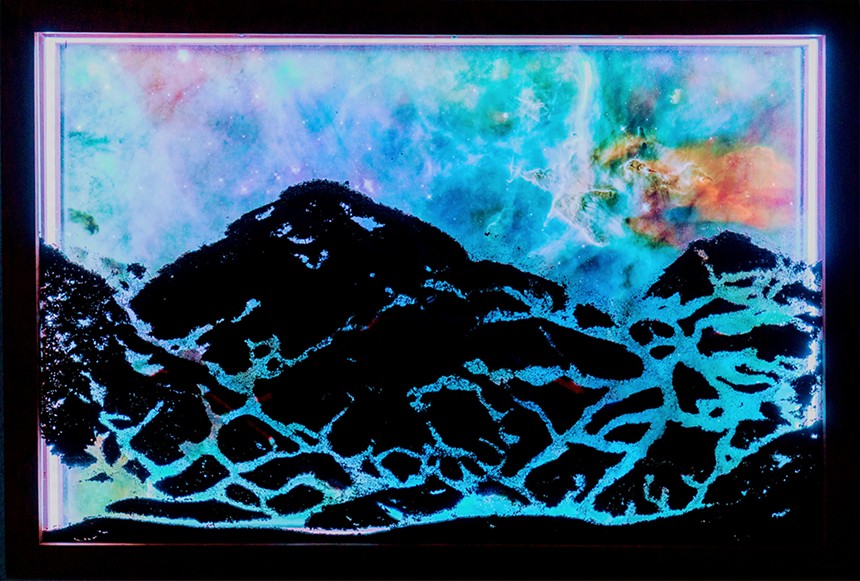

He took his new mission seriously, even acquiring a patent in 2017 for his “decorative ant farms.” They aren’t your ordinary Uncle Milton's, that’s for sure. They’re more like ant spaceships, with Lemanski using images from the Hubble telescope as backgrounds, after putting them through an algorithm and then Photoshop to make them appear even more psychedelic. As the ants plow through the soil, they create designs that look like mountain landscapes — a living work of art.

"As they dig, it exists right in the present," Lemanski explains. "Because it changes all the time, right? You go to sleep and you wake up, and they've dug another inch of tunnels. And after a week, after two weeks, suddenly it's turning into something, and then after six months, it's like there's a whole story that has a memory of...how the mountains grew and then disappeared and then grew again."

While he continued to work as an engineer, designing marijuana breathalyzers for Lifeloc, Lemanski created one ant farm after another. He's sold about fourteen (prices range from $1,195 to $1,600), with the first three purchased by his parents and sister. "I'm chasing my dreams," Lemanski explains, "and that's no surprise to them."

By now, he'd bought a house in west Denver, where he filled his basement with ant farms. "I stared at them for a long time," he recalls. "I loved it. I would just invite someone in — maybe a Jehovah Witness would show up and want to talk to me, and I'd be like, 'Let me show you something!' Then I bring them down into my basement to look at my psychedelic ant farms, and it's just, like, a Tuesday afternoon; they're not expecting it. I would go down first, and I would turn around and watch them walk into the room and see their face. Like, it was a huge joy for me, just the confusion, but also them seeing it is really beautiful."

In order to share that joy, he decided to create a gallery that would introduce his art to the public. He left his job, and with funds from his ant farm sales as well as what he'd saved from his salary, he opened Ant Life at 2150 Market Street in June.

"Anyway, it feels great to have it in a space where [people] can have that feeling, but also not in my basement. So it's been great getting it out into the world," Lemanski says.

“When my engineering co-workers came to the opening, they were surprised,” he adds with a laugh. “They were like, ‘Uh, we had no idea you were into this.'” On a wintry day, the 6,200-square-foot warehouse space is a little drafty, but the soft-spoken, mild-mannered Lemanski is cheery as he swings open the heavy door with a wide smile. His long hair grazes his shoulders, and he's wearing one of his bright, tie-dye-esque clothing designs — another gallery offering, since he realized he had to have some more marketable options if he wanted to pay the bills.

"Eventually, I realized not everyone wants ants in their house," he admits.

Ant Life has an open floor plan, somewhat separated into three rooms by jutting walls. The colorful clothing hangs along the brick wall to the immediate right of the entrance, and the designs match those of the velvety wall hangings Lemanski has created, which he calls space screens. "The concept is when you're tripping for ten hours on LSD or something, you can just have a collection of fabrics and just be swapping them out so you're not looking at the same thing and have a rotation of something new to look at," he explains.

The space screens hang on the brick wall in the second room, which also houses the ant farms and his light spaces (these are the same design as the ant farms, just without the ants). This area has no windows, but there's colorful light coming from the wall separating the main room from the clothing display and entrance. While some people have screensavers to entertain them when tripping, Ant Life has this wall covered in a projection of fractals.

Lemanski's biggest ant farm is here, still devoid of ants from the earlier freeze; he's titled it "The Shoreline of Sanity." It's four feet by six feet, and he estimates it took him 100 hours to build. "I had a vision to make more farms and make them bigger. This piece is just like the bike ride: It was the biggest I could go," Lemanski says. "I can't get material bigger. They don't make plastic bigger. There's plywood in the back; they don't make it bigger. I can't get an image printed any larger. I took it as far as I possibly could.

"You know the concept of the hero's journey, right? That's what I did," he continues. "I went on a hero's journey on that bike ride. And the last part of the hero's journey is the elixir that you come home with. Like, what do you have? What knowledge do you have to share? I came back and I built the world's largest. trippiest ant farm in this — and this, this, is the elixir."

Lemanski has a tentative plan for "The Shoreline of Sanity" that has made the ant-keeping community on Reddit question his sanity. He's been mulling over the idea of nesting several queens to create multiple colonies in one farm that's far too big to have a single queen. "I'm gonna put multiple queens in there, and they're just going to be at war," he says with a somewhat nervous laugh. "There's something dark about that, which is why I haven't done it yet. There's gonna be an endless ant war in here, with this beautiful space background. You know, they're just interesting to look at. It's an endless world unfolding in front of you."

This is not the only idea of Lemanski's that's alarmed ant lovers on Reddit. “I actually get a lot of pushback from them,” he admits. “With ant-keeping, the idea is to keep a queen and watch the queen lay babies and have a whole colony and to keep them healthy. They keep them in a plastic box; there’s no soil or anything. So they see me using potting soil, or not having a queen in one farm, or they’ll be like, ‘The lights bother the ants!’

"The ant-keeping community doesn’t like what I’m doing," he adds. "Some of them think it’s cool, but a lot of them are like, ‘That’s not the point of it.’”

He knows that the contained ant war will make those people lose their minds, but "unless you're, like, a vegan without pets," he says, "I don't think they have a leg to stand on."

Ant Life is filled with peaceful spots, though. Lemanski has never been big into alcohol or going out, which is part of why he wanted to create a place for like-minded people who prefer more intimate, deep experiences.

There are plenty of activities to keep them occupied. Hula hoops hanging on a pole in the center of the main room invite play, while bean bags patterned similarly to the space screens encourage lounging. Anyone who uses psychedelics would consider the massage chair a major perk. Another detail trippers would appreciate: a wooden table that Lemanski built with six legs, “like an ant.”

Color-changing light bars illuminate the light spaces and space screens, which can provide hours of entertainment for spunions. The screens are printed from photographs Lemanski takes or sources from Google Earth or government images, such as the Hubble, which he then puts through the algorithm and Photoshop process that he uses for the ant farm backdrops.

“I consider these closer to nature photography,” he says, gesturing to his space screens. “I need to go out and find it. On the far left there, that's a photograph of a broken tree branch I took. Just to the right of that one is a satellite image from Google Earth looking down at the mountains.”

You wouldn't be able to identify the broken tree branch, though; it appears more like an eerily symmetrical abstract painting. Ant Life visitors discuss his art as they would a Kandinsky at New York City's Museum of Modern Art, asking each other what they see and how it makes them feel, Lemanski says.

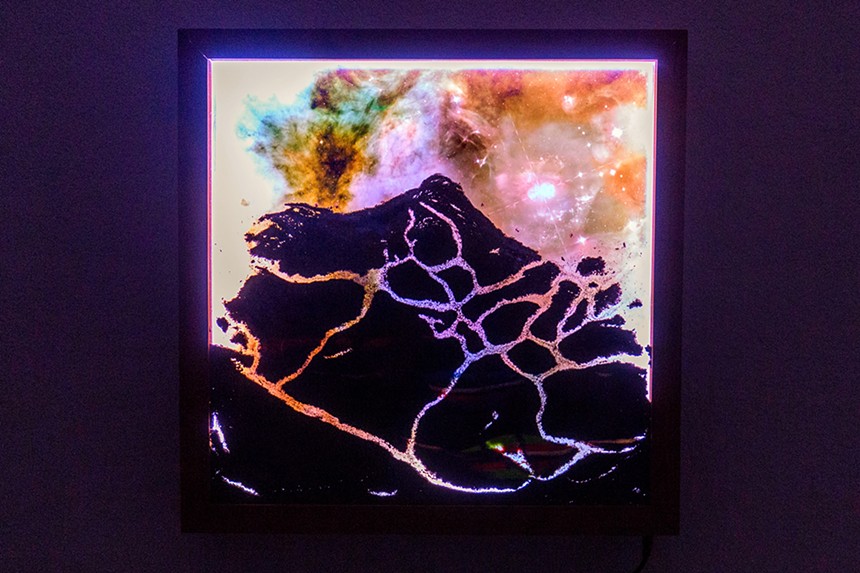

His pièce de résistance is in the back room, behind the final wall. A beanbag chair is positioned directly in front of a large, backlit, algorithm-twisted symmetric image with a color-changing light highlighting different pigments. "This is a piece I made a thousand days after my thousand-day bike ride," he says. "After going, going, going for a thousand days, I just took a moment to reflect on what I did in the mirror time frame. And I created a place so beautiful, I was compelled to stay. And that's what I've been doing: I've sat and looked at this for 100 hours, at least."

He created the work off of a Hubble image that captured space fifty light-years away. "It has a center point you can focus on," Lemanski says. "So when you're sober — but especially if you're tripping — you can hang on to that point, and it creates a sort of hallucination effect on the edges."

As with a Rorschach test, each viewer identifies something unique. A doctor who came in pointed out how it reflected human anatomy, he says. A friend who is a farmer sees pigs; another friend who loves dogs sees, well, dogs. Lemanski considers it a self-portrait of sorts, with several "celestial beings."

For now, though, you can only see the interior of Ant Life if you're going to a private event there. Lemanski admits the space has had a bumpy time finding its footing. "I don't know how to make money," he says. "I'm an engineer. I'm not really a businessperson." When he opened Ant Life, he was relying a bit on the Field of Dreams theory: If he built it, the trippy people would eventually come.

"My initial concept was to be open to the public, and I opened to the public, but I quickly realized I wasn't allowed to be open to the public," he says. "This is my first time ever opening a business. Basically, the police showed up, and they said, 'Where's your business license to operate as a business like this?' And I'm like, 'What?' ... My concept was never to have alcohol in here, so I just gave them a tour of my gallery, and they were like, 'Here's a ticket. Go to the courthouse. You gotta get your business license.'"

He had to pay a $600 fee and do 24 hours of community service for operating without the proper license. But that ended up being a blessing in disguise; he understands that a psychedelic lounge shouldn't necessarily be publicly available. "It just wasn't tight enough," he says of the early weeks when Ant Farm was open to the public. "Basically, if people want to be in here tripping and feel really safe, and then it's still open to the public and there's a bunch of people wandering in and out.... Yeah, it wasn't quite working."

You wouldn't be able to smoke cannabis in the building if it were publicly open, either, he notes: "You'd have to go out into downtown Denver just to smoke. But right here, it's an environment, and it feels really good. Just doing private events keeps it tighter for people, and it's just their friends. And honestly, it's easier for me than to be open to the public. ... Then people can use this space for whatever they want with their private events."

When Lemanski opened Ant Life, he had no idea that Proposition 122 would make the November ballot and be approved by Colorado voters, creating a whole new industry for people using psychedelics. Now, though, he realizes that he could be on the precipice of something big. "I appreciate that people can feel even safer to grow, possess and use mushrooms. For the Ant Life business, we never planned to distribute mushrooms in any way, so it doesn't affect us directly," he says. "The positive for us would be that mushrooms, and psychedelics generally, are becoming more acceptable and mainstream. And at least with mushrooms, there will be more access as the grow kits and spores become widely available."

"I designed Ant Life to be the perfect place to trip," Lemanski says. "As more people experiment with mushrooms, I hope they'll find their way to us."

Several people and companies have, with one couple even holding their wedding reception at the lounge. Ant Life is rented for about ten private events a month; most of the clients have been cannabis companies, including the Clear, Harmony Extracts, Kind Love and 0420 Inc. He had never been "involved in those industries in any way prior to opening Ant Life," Lemanski says, "though the project I was working on at my prior company was a cannabis breathalyzer. So in a way, I was on the enforcement side of those industries."

Prop 122 included a timeline to implement a 21+ legal-access framework for psylocybin by the end of 2024, and for mescaline, psilocin and DMT by June 2026. In the meantime, possession and use of the natural drugs is totally kosher, as long as you aren't using them in a public place or distributing them. Colorado has no plans to legalize public use, which puts Ant Life in a unique position, too.

For the record, Lemanski points out that "Ant Life never sells or distributes any psychedelics, cannabis or alcohol, and no one on our premises is ever allowed to sell any illegal drugs, cannabis or alcohol. All we offer is a beautiful place to be."

The space hosts two regular monthly events: Magic Makers Market, which showcases crystals and "witchy stuff," and Made by Us, which is more of a clothing bazaar. "I was flailing for the first three months, until I just really settled on private events," Lemanski says. "And then I had to figure out how to sell private events here, and that took another three months. But now we're starting to roll with it."

On February 11, Psychedelco and Shroomski magazine will use Ant Life to host Shroomski Brunch, where revelers will drink tea, eat small bites and celebrate the passage of Prop 122; tickets are $21. It's a suitable event for the space, because even though you don't need psychedelics to enjoy Lemanski's art, they are an integral aspect of the Ant Life ethos.

"I want to be a well-known psychedelic brand," Lemanski says. "I know psychedelics are healing; it's like a big thing right now. I'm about psychedelics for fun. We do it for entertainment here. And that's kind of what I want to bring to the party. You don't even have to go think on your deepest, darkest fears while you're tripping. They can come be relaxed in this space and feel really safe. We keep it a nice, tight environment for people. And then they're welcome to be around other people who are also tripping and meet people in that space. You know, it's just becoming legal, but already a lot of people trip. That community has been looking for each other. Here's the space where they can find each other."

Lemanski hopes to make Ant Life membership-based one day and welcome more people, as well as host some mushroom events. But for now, he's just enjoying the fact that he has been able to give his ant farms an audience. As his landlord told him, Ant Life is "weird enough to work."

"I think my goal has always been to sell enough ant spaces so that at any time, somewhere in the world, there's somebody tripping with their ants," Lemanski says. "Once the ants are in there, they'll be creating art and slowly dying for a year. And eventually you'll have one ant left. And you've spent a year with that ant, watching it walk around and live on your wall. And when it dies, you'll feel a little bad about it.

"But if I can get enough people to care about one ant, what else could they care about? It opens up a lot of things."