Unless, that is, he's David Bowie, a man who keeps taking imaginative risks even though his past wagers have caused him to lose and/or regain his audience far more often than any of his contemporaries. Obviously, he's no rookie: Born David Jones in 1947, he made his recording debut in 1963 and adopted his current name a few years later to avoid confusion with Davy Jones of the Monkees. In short, he knows as well as anyone how the show business game is played, and yet he consciously refuses (out of boredom, perhaps, or obstinacy) to idle too long in any one place.

These shifts in style and substance were widely embraced throughout the early and middle Seventies, thanks to the appeal of The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars, Aladdin Sane and Young Americans. But following 1983's popular Let's Dance, Bowie seemingly lost his touch; his brave but laughable 1988 attempt to disappear into a new band (Tin Machine) was merely one of several efforts the public ignored in droves. By 1995, Bowie had gone a long while between substantial successes--but rather than setting out to generate one, he came up with Outside, a craggy, not-always-accessible concept disc made in collaboration with Brian Eno, the producer of what were probably his three worst-selling Seventies platters (Low, Heroes and Lodger). And music buyers seem ready to make the Bowie-Eno team 0-for-4 from a commercial standpoint: Outside entered the Billboard album charts in the top thirty but has already gone into freefall in just its second week.

Bowie, however, is not the type of star to go into seclusion when encountering the prospect of playing rooms without a lot of love in them. He's in the midst of a nationwide tour and appears to be bearing up well, even though his support act (Nine Inch Nails) is currently a stronger live draw than he is. In fact, the presence of Bowie atop the bill actually seems to be hurting sales: In the days leading up to the trek's Denver stop (October 16 at McNichols Arena), two local rock stations were giving away tickets with a feverishness that suggested promoter panic--and one (KNRX-FM/92.1) repeatedly referred to the gig as the "Nine Inch Nails-David Bowie concert." Oh, the ignominy of it all. Bowie no doubt saw a jaunt with Trent Reznor's band as an opportunity to introduce his music to new listeners, as well as a challenge to his ability to remain vital despite being as old as some NIN fans' grandparents. But even he might not have understood how difficult these goals would be to achieve.

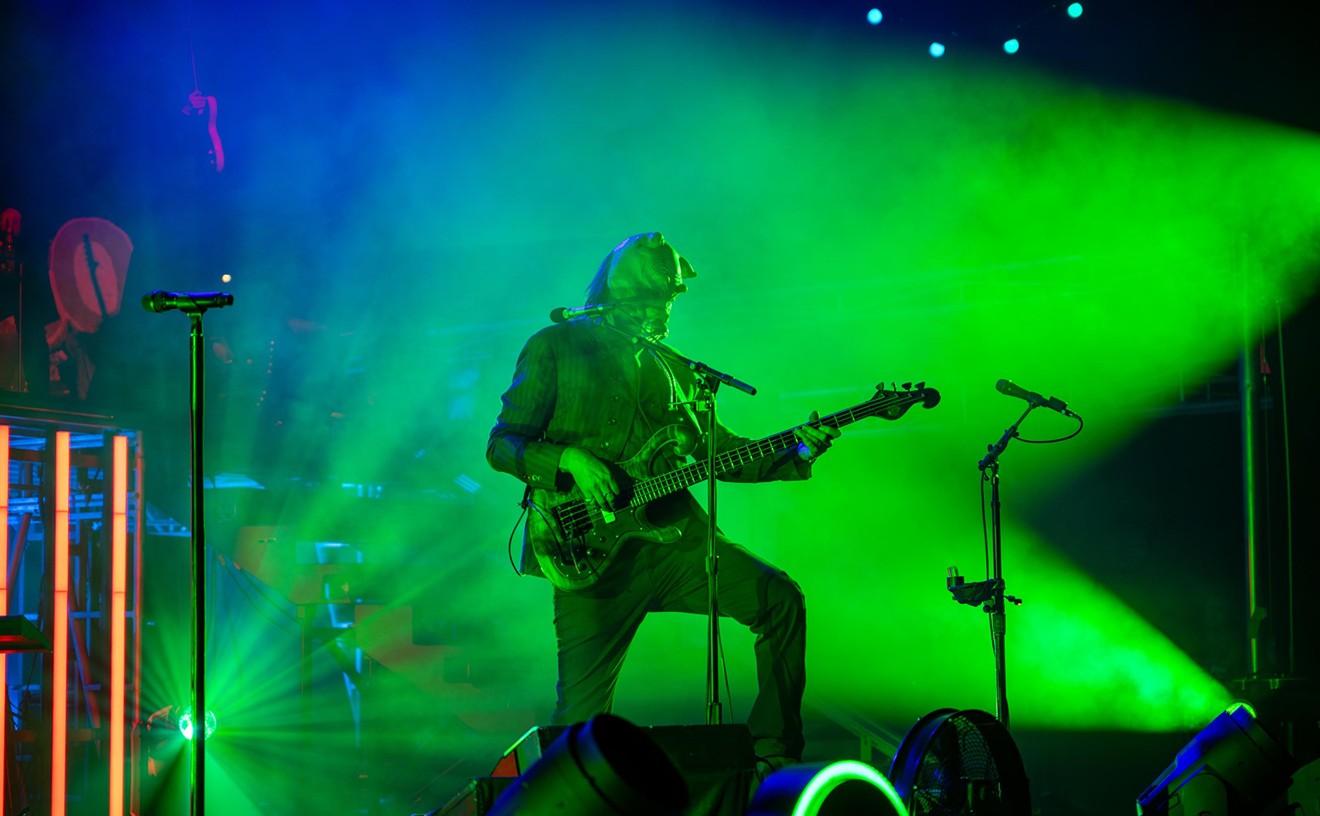

Reznor certainly didn't make it easy for Bowie. Since October 1994, when NIN last played Denver, the group has grown far stronger. Part of the reason for this improvement is technical; for example, Reznor and his helpers (two drummers, a guitarist and a bassist/keyboardist) have learned to make their sound fill an arena rather than bounce lazily around it. Also, the show was more tightly paced, rejecting long, indulgent wankfests for confident tempo shifts and a clear sense of dynamics.

Most important, though, was Reznor's emergence as, of all things, an entertainer. With his silly leather pants and Morticia Addams hair, he may not look like a standard showman, but dig beneath that pale skin and you'll find Al Jolson. On show night, you see, Reznor just wanted to make everyone happy--or maybe unhappy in a pleasantly overstimulated way. So he threw his microphone stand once or more every song; destroyed several guitars; upended numerous keyboards; tossed monitors, water bottles and anything else that the frenzied stage crew could replace or make right in the few seconds between songs; leapt about in front of the footlights like a guy who'd just attempted to mate with a broken Budweiser bottle; screamed more profanities than Martin Lawrence has used in his entire career; and roared through a collection of songs (such as "Piggy," "Closer" and "Wish") that, in spite of their scabrous surfaces, have as many hooks as anything this side of Matthew Sweet. Press coverage to the contrary, Reznor is actually a canny tunesmith who cares about craftsmanship and realizes that having a lot of nifty machines and loads of attitude isn't enough to guarantee good music. That's why so many of his tracks stick, while those offered up by a lot of his industrial brethren begin to fade from memory a few feet from the dance floor. And although the instrument-trashing and simulated mayhem at McNichols was utterly predictable and mechanical, its sheer excess rendered it charming, almost quaint. He may have been dealing in cliches, but Trent cared enough for the little people to indulge them anyhow.

Topping this assault would have been all but impossible, so Bowie didn't try. Instead, he joined Reznor for four selections--two from each of their pens. The first, Bowie's "Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps)," from 1980, made for a rough beginning--the arrangement flattened out the melody, leaving little else in its place. But NIN's "Reptile" was a thud-and-boom spectacle, and "Hallo Spaceboy" (a standout on Outside) was better than that; Reznor's and Bowie's bands, which pounded in unison, spewed out a noise that did justice to both artists' visions. "Hurt," on the other hand, may be Reznor's worst composition (it multiplies whininess to the tenth power), but he and Bowie gave it a relatively subtle and effective reading.

After Reznor gave a tiny wave and departed, Bowie tried to maintain the extravaganza's energy level, with erratic consequences. He had promised to add a few old songs to his set when it became clear that ticket purchases were soft, but the ones he selected never made Casey Kasem's heart flutter. The first ditty, for instance, was "Look Back in Anger," an impressive Lodger album track that was never released as a single (had it been, it would have flopped); later, he crooned "The Man Who Sold the World"--which was covered by Nirvana on its MTV Unplugged platter--but he rearranged it so radically that many members of the crowd didn't recognize it until it was over. The result was intriguing for aficionados, somewhat puzzling for others.

As for selections from Outside, they stood up fairly well; if versions of "The Heart's Filthy Lesson," "I Have Not Been to Oxford Town" and the title cut lacked the carefully designed murk that characterizes their studio renditions, at least they retained big beats and a passable intensity. But because Bowie, who was clad for a time in what looked like a cross between a trench coat and Mom's robe, did more standing around than boogying and hardly interacted with his supporting players, the proceedings eventually began to bog down. By the time he concluded the evening with "Under Pressure," whose pop-based structure clashed terribly with the previously established mood, and a gutless, emasculated take on 1980's "Teenage Wildlife," a goodly percentage of the NIN fanatics had abandoned the arena for the comfort of their cars.

Still, Bowie's experiment didn't entirely blow up in his face; he may not have inspired thousands to pick up copies of Outside, but he had moments when even the black-lipstick set acknowledged his credibility. He would have made more money, and probably received more acclaim, had he taken the lowest-common-denominator approach of, say, Robert Plant and Jimmy Page and played familiar material. Instead, he rolled the dice--and as long as he continues to do so, there's a chance he'll come up with the sevens he deserves.