Artists, writers, publishers and comics readers from Colorado and around the country filled the venue’s cavernous main hall. The squeak of sneakers and excited chatter echoed through the air. At one table, Nate Powell, who illustrated Congressman John Lewis’s best-selling three-part graphic-novel memoir March, drew sketches for his followers. At another, John Porcellino — a former Denver resident whose long-running autobiographical comic King-Cat has won numerous awards and inspired more than one generation of indie comics creators — signed copies of his work. The rest of the sprawling exhibitors’ section overflowed with an array of creators, from local thirteen-year-old zine-maker Jackson Maness to Larissa Zageris and Kitty Curran, the writer-artist team behind the Nancy Drew spoof Taylor Swift: Girl Detective.

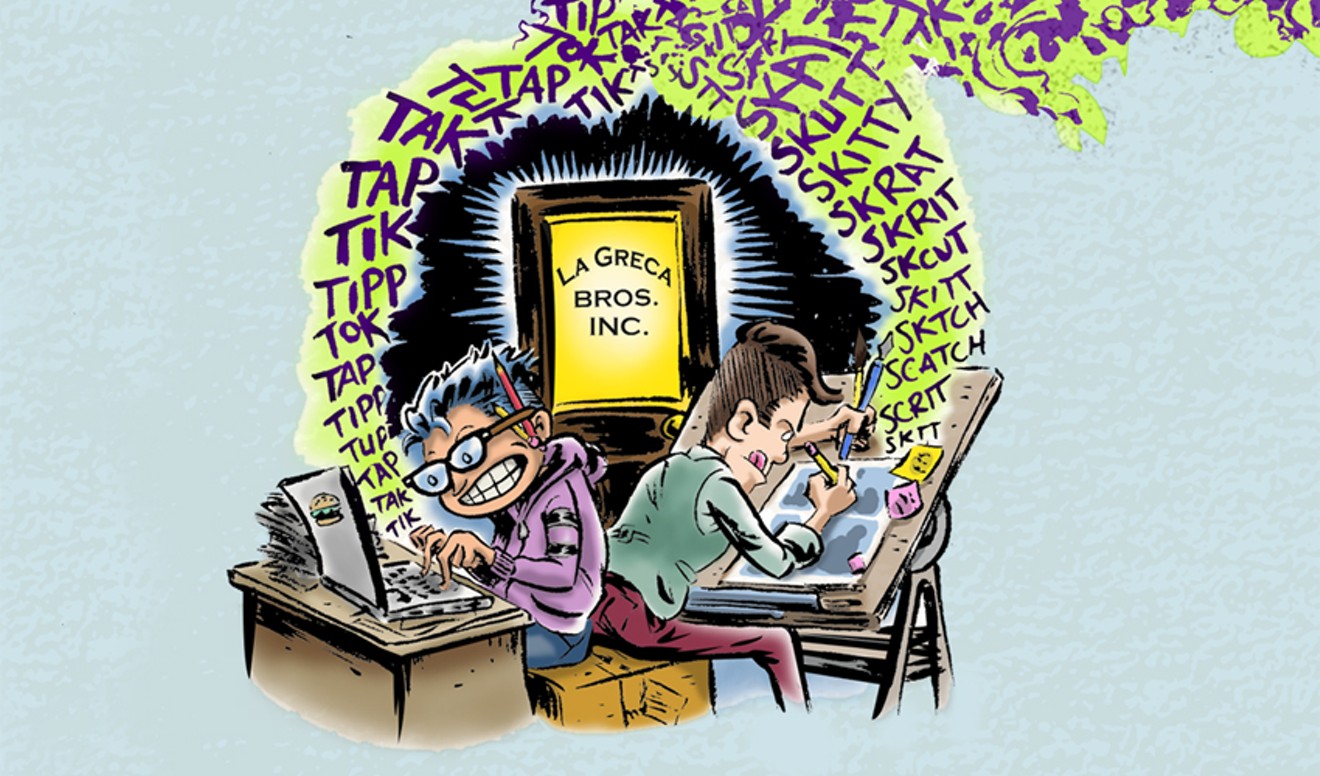

DINK: Year One, as the LaGreca brothers call it — a nod to the legendary Batman: Year One storyline that ran in the DC Comics of their youth — took place March 25 and 26, 2016, and it brought the venerable building at the corner of 18th Avenue and Sherman Street to life. “The first thing I reacted to was the people around me,” remembers Charlie, founder and executive producer of DINK. “There was this euphoric sense. There was this energy.”

“The local artistic community is fucking great,” adds Jeff, DINK’s director of creative programming. “I wouldn’t be able to name everyone, but so many people were there to support the show.”

They had plenty of reason to feel ecstatic. The LaGrecas and crew succeeded in drawing more than 2,000 attendees to a kind of con that has nothing to do with big-ticket, mainstream superheroes. Instead, DINK focuses on the smaller creators whose comics are just as apt to focus on their own lives, or the lives of historical figures, as they are to involve muscled beings with fantastic powers.

Still, DINK shares the local geek landscape with Denver Comic Con, the massive comics convention that was launched in 2012 and quickly became one of the biggest such gatherings in the country. Ironically, Charlie, along with Frank Romero, David Vinson and Kevin Vinson, founded DCC; none of them are still with the DCC organization, though. Charlie left on rocky terms in 2013, soon after the second DCC had wrapped. He calls his departure “heartbreaking.” In a way, DINK is his redemption.

As boys, Charlie and Jeff bonded over cinema, especially of the geeky variety. “I was a Ray Harryhausen and Godzilla fan,” Jeff says. And when Star Wars came along in 1977, “it was huge. It legitimized all the science fiction and other geek things I loved that people considered fringe and silly, not worth looking at.”

The two brothers are the youngest of seven siblings: Jeff was born in 1964, Charlie in 1967. They were raised in Thornton, when it was a relatively new development with little to offer kids with big imaginations. Their dad worked as an engineer for IBM — “He designed tools that would be built to enhance or maintain their machines,” Jeff says — and their mom was a homemaker, then a fast-food worker, then an elementary-school secretary. Her stint at the now-defunct Red Barn burger chain left an impression on her sons. Says Jeff, “We went through some pretty rough times. Here was a woman with seven kids, and here she was doing whatever she could to help keep the boat stable. When you look at it through that lens, someone working at the Red Barn is pretty fucking courageous.”

Their mom would drop them off at the movies during her four-hour shifts at the Red Barn. They’d gorge themselves on fare like Planet of the Apes marathons.

Being the youngest in the family, Charlie and Jeff became a unit unto themselves, delving into everything from films and comic books to theater and sports. “We’re twins, almost, in a way,” Charlie says, despite the three years that separate them. They’re still prone to egging each other on, cracking up at each other’s jokes and finishing each other’s sentences. “There’s a lot of creativity in our family, and Jeff and I were really left to our own devices. Mom and Dad would be at work, and all our older siblings would be off doing their own things.”

One older sibling, Greg, wound up being a huge influence on Charlie and Jeff. An aspiring filmmaker, Greg made stop-motion animation movies in the family’s basement. He also instilled in them a love of The Hobbit, Dungeons & Dragons, and other staples of what would later become known as “geek culture.”

“I don’t think the landscape of Thornton, Colorado, in the ’70s was a supportive environment for creative youth,” Jeff says. “In fact, Thornton was full of a lot of assholes. A lot of close-mindedness. That being the case, we very much had to turn inward to find that creative energy. Back then, you had to work for your nerd fix; you had to find it. It was very infrequent that I would have a friend at school who understood the things that I found fascinating. We come from that generation where you were very much mocked if you read comic books or you loved science fiction. We had to take it to the back yard or the basement. You had to kind of woodshed. You had to protect that.”

Luckily, Charlie and Jeff found a comrade in geekdom. In 1975, a little boy named Frank Romero moved into the neighborhood. One day he wandered into the LaGrecas’ back yard, which was teeming with kids and creativity, and he soon became a veritable member of the family. It didn’t hurt that Romero was also into comic books — particularly X-Men, which had yet to become the cultural phenomenon it is now.

“There were always comics laying around their house,” Romero remembers. “You’d walk in and there would be a comic book on the desk or on their floor, or they’re watching some old science-fiction movie, or they’re building little houses with secret rooms for their action figures.”

But the close-mindedness of their environment continued even as they grew older. “I remember Frank and I would always go to Rexall Drugs to buy comics. We were about ten or eleven years old. We would walk up 88th Avenue, constantly on guard. Sometimes we’d take the back roads. We’d only walk up 88th if we were feeling brave enough. We would have shit thrown at us from cars. Someone threw a full beer can at us once. Beer was all over my back. I was so upset.”“I don’t think the landscape of Thornton, Colorado, in the ’70s was a supportive environment for creative youth.”

tweet this

Charlie and Jeff attended Holy Cross Catholic school in Thornton, but when the church closed its school, they were forced to transfer, eventually winding up in public school. They landed at Highland (now Skyview) High, and while the transition wasn’t easy, it was the best thing that could have happened to them. “I thrived more because I found more kids like me,” Jeff says. “At public school, they had drama; they had music. They had all these things that Catholic school didn’t support.”

When Highland’s arts programs were in danger of being reduced, Jeff precociously mounted a community campaign to save them. He formed a committee and went door to door collecting signatures. They won. “If he hadn’t done that, I wouldn’t have had the artistic experience I had in high school,” Charlie says. They both became heavily involved in theater and music, with Charlie also focusing on drawing and fine art.

By high school, Charlie and Jeff had been collaborating with each other on various creative projects for years. Their first was a contest at their dad’s work. Charlie was seven and Jeff was ten. Contestants had to come up with an energy-conservation campaign, and Jeff wrote a tagline — “Bee polite, turn out the light” — while Charlie drew the accompanying illustration of a firefly extinguishing its light. Regardless of the mixed images of the bee and the firefly, they won, snagging $50 each, a fortune for a young kid in the ’70s. From there, they partnered on everything from ventriloquist’s acts at talent shows to a comic strip called The Cutie Kids, about two boys — perhaps subconsciously modeled after their creators — who gleefully mock and subvert everything they come across. “The caption would read, like, ‘The Cutie Kids are lovers of art,’ and in the drawing they’d be painting shit all over the wall,” Charlie says. “It was very irreverent. We weren’t trying to be irreverent. We just were.”

“I think that sense of irreverence was a reaction to the environment we came from,” Jeff says, “a very reverent environment in Catholic school.”

They submitted The Cutie Kids to the famed Canadian comics creator Dave Sim, whose self-published Cerebus remains one of the most successful independent comics of all time. Sim turned them down, but he did so with encouragement. It was their first contact with the professional comic-book world, but it wouldn’t be their last.

In 1981, the Colorado Comic Art Convention was launched. It was Denver’s first attempt at an annual comic-book convention, lasting until 1985 and helping to solidify the emerging fan scene in the area. “As a kid, you don’t know where these stories are coming from,” Charlie says. “You’re just reading what’s in front of you. You slowly start to realize there’s a whole team of people creating them.”

Jeff didn’t attend, but Charlie, with Romero at his side, had a life-changing experience at the convention in 1984, which was held on the Auraria campus. After being brushed off by artist Bill Sienkiewicz, one of the featured guests, for bringing too many comics for him to sign, a crestfallen Charlie was sitting in a stairwell, licking his wounds. Romero found him and said there was another artist who was not only nicer than Sienkiewicz, but was doing free drawings for anyone who asked.

It turned out to be Joe Kubert, the veteran artist who had worked on characters such as Batman, Tarzan, Hawkman and his best-known co-creation, Sgt. Rock. When Charlie and Romero approached his table, Kubert was drawing a massive freehand scene of Tarzan swinging through the jungle. The boys were entranced. Charlie asked him for a Batman sketch, and he generously obliged. Kubert’s kindness and professionalism impacted Charlie: “It changed the way I understood comics and made me think about what it really meant to be a comic-book artist.”

From that point on, Charlie never doubted what he wanted to do with his life: draw comic books. When he graduated from high school in 1985, he enrolled at the University of Colorado Boulder. He studied art, but was frustrated by the department’s resistance at the time to teaching comic-book art. After a year, he moved to Rocky Mountain College of Art + Design. The school was more receptive to comics, but he still felt restrained. By then, Jeff was already well into his own collegiate career, studying drama at Regis University’s now-defunct Loretto Heights College. Like Charlie, Jeff had a hard time fitting into the mold. “I was more into creating my own stuff,” he says.

That LaGreca streak of independence came to a head when, in the late ’80s, the brothers formed an a cappella comedy group called Minimum Wage. The band dressed up in retro fast-food uniforms, paper hats and all, and performed skits, song parodies and slapstick routines, all tied together with original music. While poking fun at fast food as well as themselves — “We were all dorks. We were all goofy. So we ended up embracing that,” Jeff says — they drew on their mom’s experiences at the Red Barn to bring empathy to their comedy.

Their love of all things nerdy also spilled over into the act. “We started infusing it with all these geek references,” Jeff say. “We would have sword fights with spatulas. There were comic-book elements to it. At the time, geek culture was not cool. So if we did a little Star Trek reference, it was unexpected. A lot of people didn’t get it. But our thinking was, let’s perform and sing about shit that no one else is willing to. Let’s do what we want to do instead of trying to fit into their world.”

Minimum Wage won a contest at the now-defunct A Cappella’s nightclub in Denver. The club offered them two consecutive summer runs.

The group was about to break up in 1991 when Jeff, on a lark, decided to try to get Minimum Wage onto ABC’s America’s Funniest People. To his amazement, it worked. Jeff and bandmate Rob Utesch were flown out to Los Angeles to perform on the show, appearing on national TV alongside hosts Arleen Sorkin and Dave Coulier.

They performed their song “Minimum Wage Rap.” To the surprise of everyone, Jeff included, they won the grand prize of $10,000. Jeff returned to Denver victorious, having vindicated his many years of going against the grain as a creative maverick. But Minimum Wage dissolved soon afterward because of the members’ conflicting schedules and priorities, just as they were poised to perhaps make bigger breakthroughs.

Charlie had not participated in the America’s Funniest People experience. Earlier in 1991, he’d left Denver for the East Coast. He was in New Jersey, having been accepted into the nation’s only college devoted exclusively to the art of drawing comics. The founder and head of that school was someone Charlie had met, briefly yet momentously, years earlier: Joe Kubert.

Based in Dover, New Jersey, the Kubert School — known as the Joe Kubert School of Cartoon and Graphic Art when Charlie attended from 1991 to ’94 — was founded in 1976. It remains a bastion for up-and-coming comics artists. For Charlie, it was a place of rebirth. “It was probably one of the greatest experiences of my own life,” he says. Not only was Kubert the founder of the school, he was personally involved with the students, serving as a mentor as well as one of the instructors. But during all his years at the school, Charlie was hesitant to bring up their original meeting to his hero.

“He was a very strong, stern, commanding force,” Charlie says of Kubert, who died in 2012. “His school was like boot camp. I was scared of him in some ways. You didn’t get really close to Joe.” Finally, on graduation night in 1994, he mustered the courage to tell Kubert about their short meeting ten years earlier at the Colorado Comic Art Convention. “I figured I would tell him about this pivotal moment in my life, and we would connect, and it would be amazing. So I finally tell him the whole story, and I ended it with, ‘And it meant so much to me, and you became my role model. You changed my life forever.’

“He just sat there quietly for a minute, then he said, ‘Is that what you think? You think I’m some kind of saint or role model? I’m not. I’m a mercenary. We do a job. We train, we go in, and we do the job better than anybody else. That’s your goal: to meet that deadline and to get that work done. I’m not here to make you happy. We’re soldiers.’” Charlie laughs at the memory. “He was basically talking like his character Sgt. Rock. He was Sgt. Rock! I was sideswiped. But still, he showed me how you can effect change in other people’s lives through the art that you do.”"That’s your goal: to meet that deadline and to get that work done. I’m not here to make you happy. We’re soldiers."

tweet this

Out of school, Charlie landed a job in the editorial bullpen of DC Comics in Manhattan, home of Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman and The Flash. It was a dream job, even considering his lowly position on the “T-and-A Crew,” or those who go over finished artwork before publication and reduce the vastly exaggerated anatomy that some comics artists use to render superheroes. As Charlie explains, “We had to do a lot of plastic surgery on the pages. Boob reduction was very common. I was fixing Catwoman’s breasts and Batman’s crotch all the time.” Along with that, he was getting occasional lettering and inking jobs — nothing glamorous, but a step toward his goal of becoming a full-fledged comic-book artist. “It was everything I could’ve wanted. I worked with a stable of artists, and it was over the top.”

Jeff, meanwhile, found his own way to New York City in 1994, looking to break into acting on a bigger stage than Denver could offer. “It was such a culture shock,” he recalls. “It was hard. I was taking every job I could get. I was working three jobs. I was kicked in the teeth.”

Between jobs, he auditioned relentlessly, eventually snaring a role in a touring production of Bye Bye Birdie. The tour was not an enjoyable experience, and it was enough to disillusion him — and bring him to a revelation. “I realized that every time I’d ever had something good happen to me creatively,” he says, “it was because of something I did myself.” In 1996 he began studying improv comedy at the newly established Upright Citizens Brigade Theater, where he was a member of the lauded troupe’s very first class. Among his teachers was a pre-fame Amy Poehler. Charlie soon joined him, and together they dove into New York’s burgeoning improv scene, rubbing elbows with the likes of Stephen Colbert, Sarah Silverman and Marc Maron, all of whom had yet to make it big.

Bolstered by their new improv chops, Charlie and Jeff revived Minimum Wage. They hooked up with the International Fringe Festival and became popular on that circuit, which led to an off-Broadway show, Minimum Wage, that ran at numerous theaters around New York. The eventual goal was to get back on TV — which they did in the early ’00s, appearing on Nickelodeon’s U-Pick Live and Food Network’s My Favorite Meal. Food Network even filmed a pilot starring Minimum Wage titled Gordon Elliott’s Door Knock Dinners, where everyday people would offer up the contents of their pantries to a gourmet chef. Minimum Wage was central to the show; it served as the musical-comedy house band, improvising lyrics to songs based on the events of the episode.

The pilot aired, but the series was not picked up. Two decades after forming, Minimum Wage hung up its paper hats for good.

Then Charlie experienced another setback: He was laid off from DC during staff cutbacks. He searched for freelance work in the hopes of remaining in the comics industry, and picked up some work-for-hire gigs for DC on licensed products, providing artwork for things like T-shirts, mugs and novels. He got a break — at Nickelodeon, no less — when it picked up a couple of Charlie’s original comic strips, "Knuckleheads" and "Rescue Rhonda," for Nickelodeon magazine.

That led to his most lucrative, high-profile, and fulfilling comics assignment to date: a regular strip, created entirely by Charlie, called "The Hair Pair," that ran in Disney Adventures magazine from 2000 to ’06. Comprising two to ten pages per issue of the monthly magazine, "The Hair Pair" starred a hamster named Squatty and a guinea pig named Bernard who embark on various misadventures in their Habitrail.

“At the time, Disney Adventures had a 3.2 million print run,” Charlies says. “The X-Men print run at the time was, like, 180,000. 'The Hair Pair' was running alongside 'Aladdin' and 'Kim Possible' strips. I was getting a lot of attention.” But when the magazine ended in 2006, he found himself once again without a steady stream of income. Minimum Wage was coming to a halt around the same time.

“Once the show ended,” Jeff says, “we sort of looked at each other and said…”

“…what do we do now?” Charlie says.

Coming from such a tight-knit family, their absence from home for so long had begun to wear on them. On top of that, Denver was no longer the cowtown of their youth; it was becoming a cultural hot spot and an attractive base for creatives. They began splitting their time between New York and Denver, gradually spending more and more time at home. Jeff was still doing a lot of writing and producing, including work for AMC and various corporate interests. He and Charlie had even collaborated on two children’s books. Charlie was continuing his tenure on a podcast called Indie Spinner Rack, which he’d launched in 2005 with co-host Mr. Phil. The first podcast devoted exclusively to independent comics, it took off like wildfire.

But the LaGrecas craved a live audience for their creativity. “As an artist, your identity gets so wrapped up in what you create,” Charlie says. “It consumes you. In a lot of ways, when Minimum Wage came to an end, it was hard to let it go. We’d had so much success with it. I was like, ‘What is my identity now?’”

He and Jeff answered that question in 2008 when they formed H2Awesome!, an outrageously costumed band that played pop-punk songs about topics like Star Wars, Planet of the Apes and The Hobbit. The idea was to mix every geek-culture thing they ever loved with the energy of rock and roll. They couldn’t have picked a better time: The film Iron Man was released in ’08, kicking off the Marvel Cinematic Universe in earnest and generating a gigantic wave of acceptance and excitement surrounding geek culture. H2Awesome! began playing concerts around the country, eventually enlisting Jeff’s girlfriend (now wife), Suzanne Slade. In conjunction, Jeff created Rock Comic Con, a moveable geek-rock showcase that provided after-hours entertainment at major comic conventions such as New York Comic Con.

One day, Charlie was back at his parents’ house in Thornton. He and Romero were in the basement, going through boxes of their old comics, reliving the days of their youth and reflecting on all that had happened to them since then. Romero had also become involved in the comics industry; in the ’90s, he became a retail manager for Mile High Comics, going on to open its megastore in Anaheim, California, which was the largest comic-book store in America at the time.“We had to do a lot of plastic surgery on the pages. Boob reduction was very common. I was fixing Catwoman’s breasts and Batman’s crotch all the time.”

tweet this

As he and Charlie leafed through the comics of their childhood and waxed nostalgic about their experience at the Colorado Comic Art Convention, an idea struck Romero: What if they started their own comic-book convention in Denver?

In 2012, that idea became a reality. Denver Comic Con was held July 15 through 17 at the Colorado Convention Center following two years of groundwork laid by Charlie, Romero and the rest of the DCC team. Included in the plan was a nonprofit entity called Comic Book Classroom, tasked with using DCC to help kids in Colorado learn to read using comics as a literary resource. Drawing on their combined industry contacts and expertise, the founders of DCC lined up funding, scheduled guests and programming, and planned on hosting an estimated 5,000 attendees. Jeff even staged a Rock Comic Con at Hard Rock Cafe alongside it.

After the dust settled that weekend, the headcount topped 27,000. DCC garnered considerable national press, and the team immediately got to work on the next year’s show. It was held May 31 through June 2, 2013, and attendance swelled to a staggering 61,000.

Under the pressure of such rapid growth and success, though, cracks started to show. Differences in organizational approaches cropped up, leading to a power struggle among DCC’s board of directors. By the end of 2013, Charlie had left the convention he’d co-created. Romero resigned soon after. Charlie and the remaining DCC leadership entered into mediation in hopes of reconciling, but that process ended without Charlie rejoining the organization. According to the terms of their mediation agreement, neither Charlie nor DCC are permitted to speak about the rift in public. For his part, Jeff says, “I believe it’s public knowledge that Charlie did not leave DCC voluntarily.”

When asked to comment on Charlie’s departure, Christina Angel, DCC’s current convention director, says, “Both our nonprofit (now called Pop Culture Classroom) and Mr. LaGreca moved on from their past professional relationship many years ago. We are pleased that he has found success in his current endeavors and, as always, wish him the best of luck in the future.”

Romero has this to say: “There were personality clashes. Approaches differed on how to run the show. A lot of the division came from that. I think it boiled down to personality and territory, haggling over who gets to do what, differences in organizational philosophy. If the con hadn’t grown so fast, I don’t think things would have gone down the way they did. It was such a stressful thing. A lot of the energy and drive behind the convention came from Charlie. I felt like it was a mistake to force him out, or to part ways with him. It was disappointing, for sure. I don’t think it was the right thing to do. But I understand that everybody involved thought they were doing the right thing.”

The bottom line was, by the end of 2013, Charlie and Romero — and by extension, Jeff — were no longer involved in Denver Comic Con. “I put my entire being, identity and resources into DCC,” Charlie says. “I considered it part of my art, and my art is my baby. I don’t know if I can express what it feels like to lose something like that.”

After a period of soul-searching and encouragement from the local comics scene, he set out to make a new baby.

DINK didn’t come in a flash, but gradually. Following his departure from DCC, Charlie says, he “was lost, trying to figure out what to do next. My head just wasn’t in the game.” A call from a friend, local artist Daniel Crosier, helped nudge him in a new direction. “Dan called me and said, ‘I know you’re not doing well, but when are you going to create your next thing? I want to help you. What do you want to do?’”

It wasn’t an easy question to answer. But after Charlie consulted with his girlfriend (now wife) Ami Heinrich, who owns the Denver PR company Tsunami Publicity, as well as other friends and confederates here and around the country, his vision for DINK began to coalesce.

“DINK emerged when we realized that Denver needs a new platform to celebrate the spirit of independent creativity and innovation within the comic-book industry,” Crosier says. “We were inspired by the underground innovators, the DIY ethos and the punk-rock ideology here in Denver. At the same time, we loved the idea of being that small beacon that brings in our extended creative family on a national level as well as internationally.”

Along with a team consisting of local luminaries in the scene such as Jim Norris of Mutiny Information Cafe, Ted Intorcio of Tinto Press, Sara Wilson of Nerd Nite Denver, and Jon Price, a transplant from New York who plays guitar in H2Awesome!, Charlie started drawing up blueprints for DINK.

“You can be a powerhouse, but there are times when you lose that sense of power; you need help from those around you,” Charlie says. “That’s what I needed, that reminder from people. Eventually, DINK came about.”

With Jeff at his side as creative programming director, Charlie forged partnerships with like-minded organizations such as the Denver Zine Library. The goal was to reconnect with the basics of comics as an artistic force, apart from all the glitz and buzz of big media. “I got back to what was most important to me: words and pictures,” Charlie says.

On April 8 and 9, DINK: Year Two will take place at its new location, the McNichols Building. It’s a step up for the con in terms of space, visibility and legitimacy. “It’s a big shift,” Charlie says. “We have a bigger space [than last year], probably 6,000 more feet. The McNichols Building is way more of a modernized building than the Sherman Event Center, but it’s still historic. I want to keep DINK in a special kind of space. Every show has to have its own identity and energy and flow and vibe. That lays the groundwork for the experience of the entire show.”

Adds Jeff, “I feel like every comic convention around the country, with some exceptions, looks and feels the same now. They all have that stale, fluorescent feeling.”

DINK most definitely does not. Vibrant, eclectic and diverse, the lineup for 2017 is topped by Jaime, Gilbert and Mario Hernandez, creators of the massively influential and acclaimed indie comic Love & Rockets, which celebrates its 35th anniversary this year. Returning is Denis Kitchen, one of the key players in the underground comics movement of the ’60s and ’70s; he’s part of DINK’s focus on comics as a countercultural force, which ties into the con’s pot-friendly and environmentally conscious ethic. Last year, a Cannabis and Comics panel was part of the programming, and DINK aspires to be the greenest comics convention in the country. The convention’s nonprofit component, Camp Comic Book, is planning to provide literacy retreats for underserved kids in the Denver area.“You can be a powerhouse, but there are times when you lose that sense of power; you need help from those around you.”

tweet this

“I was actually surprised DINK did so well last year,” Charlie confesses. “Let’s be honest: When it comes to comics conventions, DINK is not the big blockbuster summer movie; it’s the arty film-house movie.”

Signing the Hernandez brothers as the headlining guests for DINK: Year Two was a major coup. Like the LaGrecas, they’re a group of siblings who have created from scratch their own niche in the comics world. Their upcoming appearance at DINK is also a boon for Denver fans, including Charlie, who’s been influenced by Love & Rockets since the ’80s.

“We don’t have the most fans, but, boy, are they dedicated,” says Jaime Hernandez. “Being able to create a body of work all these years and getting the support that has allowed us to continue has been great.”

For all his passion for independent, creator-owned comics, Charlie still equally loves the iconic characters of his youth. He recently scored a dream gig drawing an upcoming revival of the Casper the Friendly Ghost and Richie Rich comic-book series. But "there’s a comfortable space for us in the alternative, in the independent, in the not fully appreciated or fully accepted. I think there’s a warm place in our hearts for that because we grew up that way. We grew up learning to love that stuff that wasn’t widely accepted, yet wanting it to be more accepted. We want that validation. We wanted people to understand why the stuff we love is so good. What do you do when you’re hurt? You go back to what makes you feel good. You go back to what heals you. In the end, those who care about you are your salvation. And your art is your salvation.”

“What did Carrie Fisher say?” Jeff asks, finishing his brother’s thought. “‘Take your broken heart, make it into art.’”