Thomas Mitchell

Audio By Carbonatix

A co-op selling support services with a free side of psilocybin mushrooms has caught the attention of the Denver District Attorney, but legal experts admit that current state laws have loopholes that might allow the co-op to escape punishment.

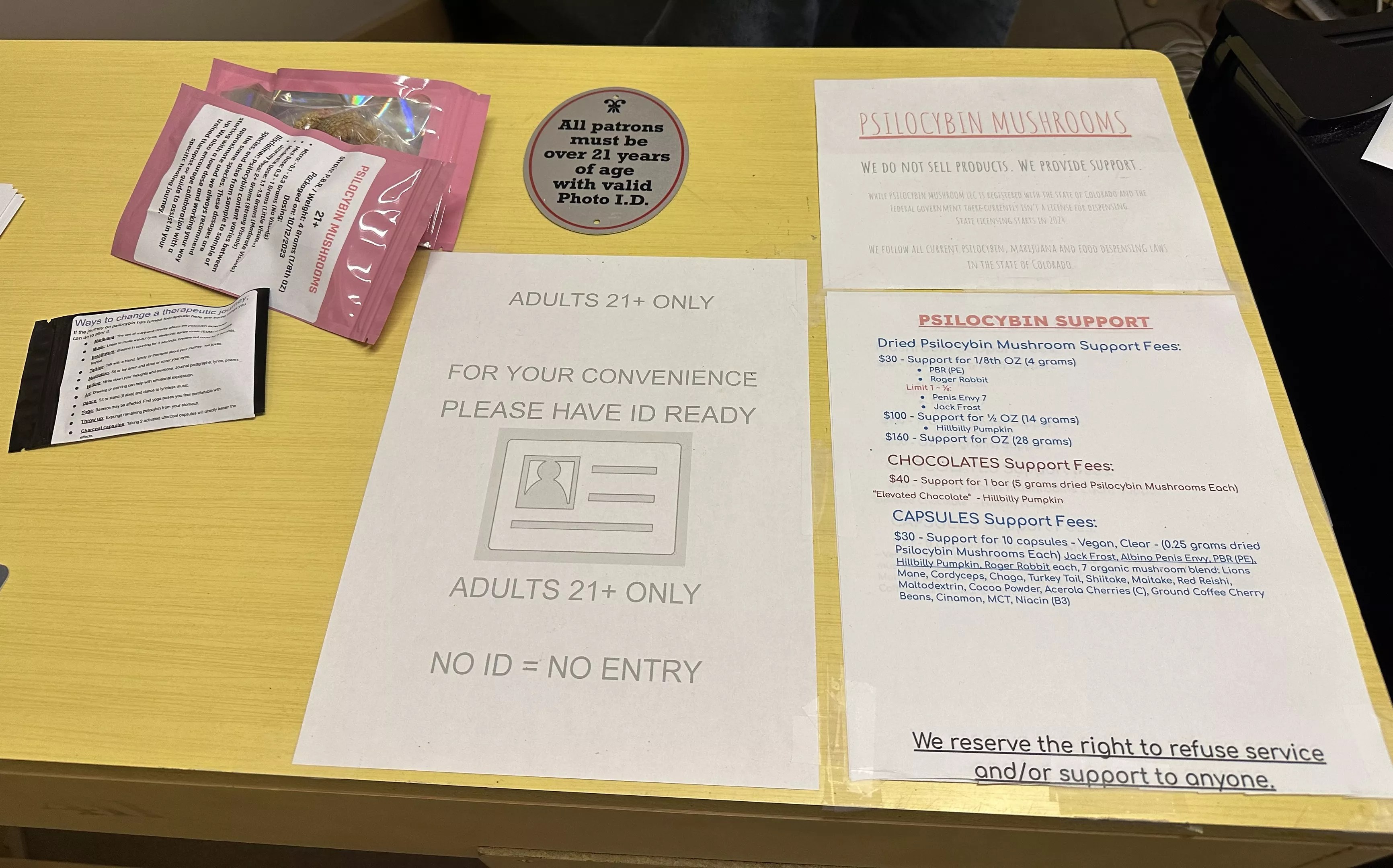

Darren Lyman insists that he is running a support center for those in need of natural medicine inside his studio at 800 West Eighth Avenue. By calling ahead, an adult can set up a visit to chat with Lyman about psilocybin’s intoxicating effects and its potential to treat mental ailments such as anxiety, addiction, depression and traumatic stress.

The session typically costs $30, and the four grams of mushrooms that are provided at the end are free, he says. If you pay for more support, you’ll get more mushrooms.

Lyman operates his business openly, even advertising in Westword. He argues that he is operating legally under Colorado’s new Natural Medicine Health Act, or Proposition 122, the initiative approved by Colorado voters in November 2022 that decriminalized certain psychedelics and legalized medical psilocybin.

Denver DA Beth McCann and a handful of local psychedelics advocates who have pushed natural medicine initiatives in Colorado aren’t sold on the co-op’s interpretation, however.

“I don’t know what we’d call him. It’s interesting to me that he is kind of distributing psilocybin,” McCann said during a Denver Psilocybin Mushroom Policy Review Panel meeting on November 30. “It’s a weird thing, but it seems to be circumventing the regulatory [structure] to me.”

Under the new state law, adults can now cultivate, possess and share psilocybin mushrooms, plants with DMT and mescaline (except for peyote), and cultivate and possess (but not share) ibogaine. Applications for psilocybin production facilities and supervised use sites are expected to be available next year or early 2025, but operators of such businesses must first be licensed by the state.

Still, McCann admitted that she needed to learn more about the mushroom co-op before taking action, because “criminal law is pretty vague unless you’re really selling it, so I don’t know.”

Lyman insists that he’s selling services, including advice, informational pamphlets about psilocybin use, and activated charcoal capsules – a common method of reducing body absorption of psilocybin when someone has bitten off too much – not the psilocybin itself. That, he stresses, is free. In the push for Prop 122, its leading proponents repeatedly stated that the measure would not create a retail aspect for psychedelics, and state officials with Colorado’s new Natural Medicine Division (NMD) have echoed that message.

During Denver’s psilocybin panel meeting, Healing Advocacy Fund Colorado director Tasia Poinsatte called the co-op “kind of a work-around” of the intention of Colorado’s new psychedelics laws. A nonprofit organization that advocated for Prop 122, the Healing Advocacy Fund is now playing a role in the implementation of both Colorado and Oregon’s new psychedelic laws.

“I think the city could put out some guidance on what these terms mean,” Poinsatte said during the panel meeting. “I think the problem is that people are self-interpreting these provisions, and it would be nice to have some clarification on it.”

Earlier in November, the Healing Advocacy Fund had sent out an announcement regarding a Westword story about Lyman, stating that “charging a fee for psilocybin mushrooms and advertising for this activity is not protected under Colorado’s new psychedelics law.”

Critics of his co-op “don’t understand how the support center operates,” Lyman says. “I don’t sell products. I provide support.”

Psilocybin board member Sean McAllister said he agreed with his peers from a philosophical perspective, but added that the legal area in which the co-op operates is “a bit more gray.”

According to McAllister, a cannabis and psychedelics attorney, Colorado’s natural medicine laws now allow people to share decriminalized psychedelics in the context of spiritual guidance, counseling, community-based healing and other supportive uses. The natural medicine itself must be free, he said, but another provision states that people can charge for bona fide harm-reduction services or support services.

And those services are “currently undefined under the law,” McAllister noted.

“There would be a way for somebody to give away medicine for free and charge for bona fide harm-reduction or support services,” he said during the meeting. “This is a bit of a gray area on the spectrum right now.”

An eighth of Penis Envy mushrooms is free after paying for in support services at the Denver co-op.

Thomas Mitchell

McAllister, Poinsatte and attorney Joshua Kappel, a co-drafter of Prop 122, all said they believe that advertising magic mushroom sales or even implying such sales are likely violations of psychedelics law, but they fall into gray areas, too.

“It’s not clear what the penalty is if you’re advertising. If I’m a sitter and I want to sit with somebody [after they do psilocybin], and I put that on the back of a Westword, the fact that I was advertising wouldn’t mean I’m selling mushrooms. So it’s just not clear what the penalty is for advertising, either,” McAllister said.

Psilocybin board members said they’re waiting for the Colorado Legislature to pass clarifying bills or future rulemaking within the NMD and Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies (DORA) that would further define permitted and prohibited retail activity.

“Then there would be an enforcement mechanism,” McCann said.

Although psilocybin dispensaries similar to cannabis stores were never the intention of Prop 122, according to the Denver board members, there will likely be commercial production of items such as psilocybin edibles, which are intended to be sold only at licensed facilitation settings.

Colorado law enforcement agencies cracked down on cannabis operations that used similar claims of providing free products for monetary donations after statewide recreational and retail legalization was approved by voters in 2012. With retail legalization, however, came more commercial and criminal definitions, as well as the ability for local governments to ban any form of marijuana businesses.

The psychedelics initiative allows local governments to enact time, place and manner regulations on psilocybin businesses and supervised use sites, but no outright bans are allowed within counties and municipalities.

“The big question for local governments is ‘How do we want to zone these businesses, and what does that look like?'” Kappel asked during the meeting. “Is this a therapist office? Is this a retreat? Is this some sort of bed and breakfast, or is this something completely different?”

Created as part of a voter-approved measure in 2019 that decriminalized psilocybin, the Denver Psilocybin Mushroom Policy Review Panel took a brief hiatus in 2023 after Prop 122 passed. But the panel is expected to take a leading position in Denver’s approach to its medical psilocybin rules, with expanded roles for city officials from law enforcement and public health agencies.

The board partnered with the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), a national nonprofit in psychedelics research, in 2020 to create a harm-reduction training program for Denver first responders in emergency health care, law enforcement and mental health. The program, almost three years in the making, is expected to be ready for distribution before the end of the year.

Going forward, Denver’s psilocybin board plans to help create educational materials or work with Denver City Council to create a public awareness campaign about Colorado’s quickly changing psychedelics laws.

“I guess that makes sense, given the conversation we just had,” board director and Denver psilocybin activist Kevin Matthews said before ending the meeting.