Why? The answer has a lot to do with several of music journalism's dirtiest little secrets. You see, pop-music critics are always looking for stories -- but far too many columnists routinely undertake their searches in the most obvious places imaginable. (Heaven forbid they should actually pay attention to a CD by an obscure act, decide on its quality without regard to its popularity among the public and/or their peers, and research the group's history in an effort to uncover intriguing details that haven't previously been beaten to death. That's too much like work, dude!) Moreover, when a ready-made tale surfaces, such scribes eagerly compromise their analytical expertise in order to gain access, pump up the faux-conflict, or otherwise make their jobs as easy as possible. Would the narrative flow more smoothly if a performer's music was crummy? Then his stuff sucks like a hooker with nothing in her pocketbook but a rent-due notice. The chronicle would improve if an artist's material was good? Then his offerings are more precious than anything in Fort freakin' Knox.

For proof, look no further than the Wallflowers. The combo's recordings thus far have been underwhelming in the extreme, employing middle-of-the-road riffs and timeworn rock tropes in a thoroughly conventional manner. But that hasn't prevented Dylan, son of Bob "The Voice of an Old Generation" Dylan, from receiving the full-scale Hosanna Treatment. Rolling Stone, which once sacked a staffer for refusing to rave about Hootie & the Blowfish at a time when keeping the group happy was fiscally savvy (seems like ages ago, doesn't it?), recently handed its cover over to big-eyed Jake and subsequently named him one of its "People of the Year." (The magazine also argues that the Backstreet Boys' "I Want it That Way" is one of the ten greatest pop songs of the past forty years. I had my money on something by Bobby Sherman.) Likewise, mag and newspaper journos across the nation, including one at each Denver daily, have lately churned out lighter-than-helium pieces about the younger Dylan, focusing mainly upon his newfound willingness to discuss his dad -- a canny move on his part. (By continuing to steer clear of the topic, he ran the risk of frustrating the very folks who've helped him rise to prominence.) These articles refrained, for the most part, from comparing (Breach), the Wallflowers' latest disc, to Papa Bob's top long players, which is only fair. But they also avoided mentioning the CD's towering tediousness, instead portraying it as unexpectedly challenging -- and in a way it is, I suppose. While checking it out, I had to fight to remain conscious.

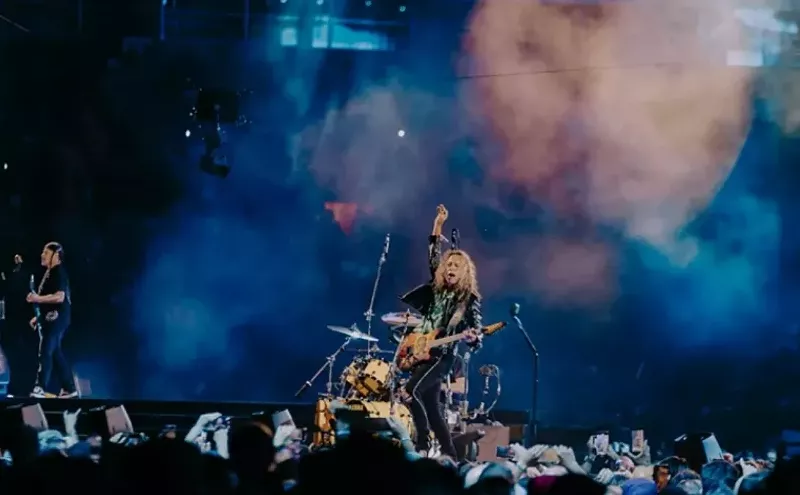

Granted, (Breach) isn't unlistenable, but the album's generic, been-there-done-that-a-trillion-times-before feel makes it difficult not to see ulterior motives in notices by the likes of allmusic.com reviewer Stephen Thomas Erlewine, who called (Breach) "the finest straight-ahead rock album of 2000." Hunger for the good copy that another talented Dylan would supply may not fully explain such enthusiasm: bandwagon jumping or creeping old-fartism probably come into play as well. Still, the quintet's live turn at the Fillmore suggested that these Wallflowers would never have been invited to dance had their songs and their skills been their only attributes.

Everlast, who preceded the Wallflowers to the Fillmore stage, helped give Santana a little hipness infusion by opening up for the veteran string-strangler's summer tour, and he fulfilled the same role for Dylan; his hip-hop background -- he once led House of Pain -- provided modernist cred, but not so much that it scared off the oldsters in attendance. Unfortunately for Jakob, Everlast was unexpectedly effective, winning over a crowd that clearly knew only two of his songs ("Put the Lights On," a collaboration with Santana from the Grammy-hoarding Supernatural platter, and the set-closing hit single "What It's Like"). With his pleasantly raspy voice and ardent delivery, he gave new ditties such as "Black Jesus" and "Black Coffee" (like most Caucasians with a history in rap, he has some color issues) a funky sonic buzz, replete with DJ scratching and the occasional sample, that sounded plenty contemporary, notwithstanding the acoustic guitar strumming at its heart.

By contrast, the Wallflowers eschewed any and all current touches in favor of classic instrumentation: bass, drums and guitars, with keyboards thrown in for atmosphere. But even though the supporting players (Rami Jaffee, Greg Richling, Michael Ward and Mario Calire) bashed away more energetically than they do on plastic, they seemed to mistake loudness for passion. Sometimes this ploy worked: an encore rendering of the Blur smash "Song 2" that Richling, Ward and Calire blazed through, sans Dylan, received the most exuberant response of the night even as it made the next ditty, the Dylan-crooned "Baby Bird" -- a bonus track from (Breach) -- seem impossibly weak in comparison. Besides, the cliches in which the other Wallflowers trucked (Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers organ fills, slide solos straight from late-'70s Jackson Browne recordings) were only partially their fault. Dylan is the songwriter, after all, and his compositions rigorously hew to predictability, taking the most obvious turns at the most obvious times.

This approach is common in the heartland rock to which Dylan aspires, but those who trascend the genre have done so by infusing its rudiments with so much muscle and sincerity that originality is no longer an issue, and he simply isn't equal to the task. "Sleepwalker," the first single from (Breach), has a couple of chord progressions that stick out, as do previous chart-scalers like "One Headlight" that the band trotted out every time momentum flagged. However, "Murder 101" and others recall outtakes from lesser Springsteen discs, like Lucky Town, that even aficionados haven't spun since two weeks after they came out due to a sense of obligation. They wouldn't make most people lunge for the radio dial, but neither would they inspire them to turn up the volume. Likewise, Dylan's lyrics imply a depth that they never attain. Take "Letters From the Wasteland," a song whose title waves its importance like a flag but settles for hackneyed images such as "It may take two to tango/But boy, just one to let go" -- a couplet that only people who count using their fingers could possibly see as insightful.

Dylan's stage presence further undermined any pretensions toward profundity. Dressed like Mike Meyers in his "Sprockets" sketches on Saturday Night Live, he wiggled a time or two while in the spotlight and occasionally lowered his lids to simulate introspection. But when the music stopped and he was called upon to communicate directly with the paying customers, he reverted to gently sarcastic banter whose subtext escaped him at times. For instance, he pretended at one point to be confused about which Fillmore he was playing -- the one in Denver or its San Francisco precursor: After reminiscing about a video he'd filmed in the venue several years ago (yes, it was really shot in the City by the Bay), he said, "Janis Joplin, Jefferson Airplane -- a lot of history here." But he didn't seem to realize that anyone in the room could do a similar bit about him: "Saw Dylan at the Fillmore, and he looked so young! But he didn't do 'Like a Rolling Stone,' and he was really boring..."

That's no exaggeration. As the Wallflowers' set wound down, Dylan launched into a rendition of David Bowie's "Heroes" (originally cut for inclusion in the blockbuster-wannabe Godzilla) that was overtly faithful, but he somehow managed to replace the mystery and melodrama of the original with little more than amplification. Even worse was another classic-rock fave that was rolled out after "Baby Bird" -- the Who's "Won't Get Fooled Again." Listening to the familiar keyboard intro, I found myself thinking, "He's got to have a good reason to cover the single most overplayed song in the Who's catalogue. He's going to do something different with it -- give it an unexpected twist." But no -- the Wallflowers just ran through the damn thing like a million bar bands before it, and a million more yet to be born.

Will music lovers get fooled again, too? Maybe not: Despite the hoopla that's surrounded the arrival of (Breach), the album is tanking -- at press time, it was number 81 on the Billboard album roster and falling fast -- and the Fillmore concert fell considerably short of selling out. But even if Jakob Dylan soon goes the way of Julian Lennon, he won't be the last over-ballyhooed celebrity offspring to be touted as the Next Big Thing. When music writers have white space to fill, they'll grab for the most promising candidate available -- whether he has something to say or not.