Before heading to the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston to earn his master's degree, Tyler Gilmore spent a lot of time in Denver as the former music manager of Dazzle, as well as composing and leading the Ninth & Lincoln Orchestra, a forward-thinking large jazz ensemble that he founded in 2005. Gilmore returns to Dazzle this week for the world premiere of his new work, "A Rambling Stretch," which is a musical portrait of the area he grew up in: Riverton, Wyoming and the surrounding Wind River Indian Reservation. Gilmore teamed up with noted local photographer Gary Isaacs for the project, and his photos will be projected as a visual element during the show tomorrow night. We spoke with Gilmore about what inspired the piece and how the music reflects the area that influenced it.

See also: - Thursday: Tyler Gillmore's Ninth & Lincoln Orchestra at Dazzle, 1/3/13 - Ninth & Lincoln Orchestra is working hard to expand the boundaries of jazz - Ninth and Lincoln founder Tyler Gilmore strays from previous form on Static Line

Westword: Tell me about the new piece you'll be premiering at Dazzle.

Tyler Gilmore: It's something I've wanted to do for a long time. I always kind of wanted to have a reason to explore the area I grew up in, thinking about how it affected how I write music or how I approach the building blocks of music and all that.

So I was talking to this department at school, which is called the NEC Entrepreneurial Musicianship Department. They have this grant program, and I was able to get funding through them to take a photographer up to where I grew up, which is right in the middle of Wyoming. The town is called Riverton, and it's surrounded by the Wind River Indian Reservation, which is a combination of the Arapahoe Indian tribe and the Shoshone Indian tribe -- each on different sides of Riverton.

I grew up with some of that culture and being a part of the predominantly white city that's sort of stuck in the middle of their Indian reservation. There's a lot of conflict, weirdness, and, in a way, there's subtle racism, like racism I didn't even pick up on as a kid. I just sort of began to start seeing it as I would go back, after I'd moved away or talked to people, and then doing research for this project. I learned a lot about the history of all that.

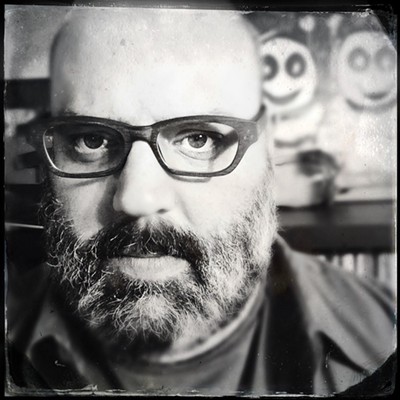

So I got the funding okay on that, and I took Gary Isaacs, who's a Denver-based photographer, up there, and it was super interesting to take somebody who has never seen the area. Gary's a real sort of heart-on-his-sleeve sort of a guy, and he was just sort of talking through all of his feelings and observations and whatnot while we were there. I talked to him about growing up there and what my experiences had been. It was interesting to sort of see through another person's viewpoint and have him working with my viewpoint and how I wanted to portray the place.

We spent three days up there. We spent time in areas that were specific to my childhood, like schools I went to and places my mother took me and things like that. And then we also went around the town and looked for places that were interesting and seemed unique. We also went out on the Indian reservation and took a lot of photos in areas there that are unique, which is actually pretty easy because there's a lot of out there that feels very Wyoming in a way.

There's a certain kind of feel to land formations and whatnot around where I grew up. It's kind of east of really mountainous areas of Wyoming. It's kind of a flatland but it's also very high flatland. It's technically a desert. It's really dry. It's pretty flat but there are also rolling hills and interesting land formations.

Anyway, we took photos in all those places and I also took a bunch of video and audio that's going to be involved. Actually, I don't think the audio is going to be involved in this first performance. I plan to grow this thing as I perform it more and more. So I don't think the audio is going to make it in this time but there's going to be a lot of video and then his pictures.

So, we got back, and he kind of disappeared into the Gary Isaacs lab and spent a lot of time with the photos, and then they would sort of just trickle out to me -- the ones he thought were special, which was interesting. I imagine all photographers work like this, but he took a ton of photos. He probably took 1,000 photos while we were there.

Then he just sort of slowly sifts through them and sees which ones jump out at him. So then they would start trickling out, and I would sort of give him directions, like, "I like where this one is going" or "I don't necessarily see a place for this one" or "spend some time with this one and see where it goes."

Then after we had the photos together, which turned out to be ten or twelve, I believe -- about eight of them are going to be involved in this first performance -- I started writing... I started doing some of the writing before the photos trickled in because I just sort of had a feel where the whole thing was headed after all of our conversations and being there. As the photos came in, I started thinking about musically what's going to pair well with them, and how do I want to, in a way, sort of color these photos with sound.

A lot of times I found it was really difficult to find the right sort of musical tone for each image because the music, it sort of imparts my subjectivity on the photos, which is great, but at times, I want it to be a little more objective and sort of open for interpretation.

In the end, I tried to focus on the space and starkness out there because there's just so much unused land that is just around out there that nobody even thinks about. There are people who will have a house and a couple of acres and just have their stuff sort of sprawled over these acres. You'll see old beaten up cars sitting off a half a mile away from somebody's house. Then a barn that nobody's used for twenty years. Just all these things in various levels of decay sort of spread around a home where a family still lives.

It's so different from being out on the East Coast. So, the idea of space ended up being a huge part of it and then, sort of, in a way, like the loneliness that can come along with that. Like being a child, an only child, from a small family -- it was always like I wouldn't say I grew up feeling lonely all the time, but there was definitely something to that, like just sort of a lack of people. It's part of the reason I was excited to get to bigger cities.

Gary noticed it right away when we were there -- like, where are all the people? Everywhere we had gone, like in the city -- places where you'd think people would walk around in the neighborhood and the main street -- there's just not that many people ever around. It's just a different thing. So I tried to explore what that's like, what it was like growing up in that way, physical space and also social space. Then also the beauty of it and how sentimental it is for me and hopefully in some degree for the audience by the end of the whole thing.

How would you say it differs from some of your other Ninth & Lincoln material?

I was really inspired by the textures of the images. I guess, again, like that starkness, a lot of it matches that in a way. The music doesn't sort of speak to you directly and try to take you on some sort of narrative path. It just tries to exist along with the photo and in sort of one place and allow that place to be enough. For example, it's not going to give you a melody and then give you a development of the melody and then give you a solo and then back to the melody, sort of all those classic formal things. I tried to move towards just creating spaces to accompany the photos and just let them be.

Would you say it's more ambient in a way, or minimalist?

Yeah. Totally. I love music in both of those worlds. I don't think gotten quite so far in either direction that people would call it that. But there are some ambient moments. It's like stretching in that direction from what maybe the other things I've done have sounded like.

Is each piece based on particular photograph?

Kind of, sort of, that was the original plan. But the whole feeling of the project sort of ending up leading me throughout all of the music. I don't know, I felt like the overall emotional scope for the music before, and while the photos were coming in, like beyond just associating one with each photo. So there's one or two photos for every piece, and some of them could apply to a couple of pieces because they touch on various things that I tried to get at.

When I started bringing in the video, that sort of took on a life of its own and started inspiring the music, too. I found a bunch of footage that I didn't take when I was there but other stuff that felt pertinent to the project; for example, there are all these videos on YouTube of rodeo. I grew up going to rodeos, and I found all these videos of rodeos that would have been the ones I would have gone to in Riverton.

I ended up using a ton of this rodeo footage for one of the pieces, but that footage sort of creates a contrast that sort of builds to this moment where the music arrives at a new thing and then a photo comes in of something entirely unrelated to rodeo. It sort of like builds a juxtaposition. So it ended up being more in a way like a little more photo piece, photo piece...

I read that an article in the New York Times inspired this whole thing, right?

Yeah. Absolutely. It came out last year, and it's about how there have been all these reform efforts to clean up problems with violence and teen pregnancy rates and whatnot in Indian Reservations and how the Wind River Reservation has been the sole resisting reservation that has not accepted reform. Not necessarily by choice, but they haven't been able to get cleaned up. So there's still a higher murder rate and all these things.

It's interesting because it's fairly low population. It's not something you ever hear about but it's per capita the numbers are really high. And it's not something I was aware of, honestly, as a kid. Like, you knew there were parts of the Indian reservation that you probably shouldn't go, and I didn't have a great sense of how marginalized the society was, but then realizing going back and growing up, and then reading that article it was like, "Wow there is so much going on there than I had a feel for." That was one of the things that sort of spurred me to try to bring this thing together. Since I worked with Gary before, I think I had a feeling that his tendencies would work well for what I wanted to create.

Follow @Westword_Music