Audio By Carbonatix

This is the fourth installment in a five-part series about gentrifying Denver neighborhoods, including Five Points, Cole and Whittier.

Globeville has long been one of the most economically challenged neighborhoods in Denver, where residents live close to industrial plants and the expanding highway system. As a result of its proximity to rapidly growing sections of the city, Globeville today is starting to see some of the gentrification that has already struck nearby areas such as Five Points, Cole and Whittier full force. But historical data reveals that signs of these shifts began appearing years earlier, though their import wasn’t recognized at the time.

The information was culled from the Child Opportunity Index 2.0, a mammoth database unveiled in January by Brandeis University. The project examines the 100 largest metro areas in the United States, including Denver, at a granular level, neighborhood by neighborhood, to reveal the sort of inequality experienced by many young people, particularly children of color, and it served as the foundation of our post headlined “Study: White Children in Denver Have Huge Edge Over Hispanic, Black Kids.”

At our request, a team headed by Clemens Noelke, research director for the Institute of Child, Youth and Family Policy for Brandeis’s Heller School of Social Policy and Management, pulled together facts and figures for a number of Denver neighborhoods, including Globeville, by drawing from the U.S. Census tracts. The main sources are American Community Surveys that the U.S. Census Bureau pegs to the years 2010 and 2015, though they actually cover wider periods: 2008-2012 and 2013-2017. As a result, they show what led to the conditions and scenarios being experienced by Globeville’s citizenry today.

The Child Opportunity Index 2.0 collected data on 72,000 census tracts nationwide in association with 29 indicators. Each factor is weighted according to how strongly it predicts health and economic outcomes, with the results combined to create a single opportunity score between 1 and 100. The bottom of the scale represents the 1 percent of kids who live in neighborhoods with the lowest opportunity scores, while 100 designates the neighborhoods offering children the best odds of reaching their full potential.

It’s important to keep this range in mind when examining Globeville’s overall numbers from the 2010 and 2015 reports, as measured against both the national average and Denver’s. For the former, the neighborhood registered 7.0 and 12.0 in the reports – distressing numbers, but not nearly as low as those for other parts of the city. Still, the 1.0 rating for 2010 indicates that Globeville’s score was the worst from an opportunity standpoint for Denver as a whole, and it only increased to 3.0 in 2015.

Here are some other revelations, as sorted into several broad categories.

Demographics

As families found themselves priced out of Five Points, Cole and Whittier, which started undergoing gentrification earlier, many appear to have wound up in more affordable Globeville. The number of children in Five Points went up by just seventeen kids, and both Cole and Whittier saw decreases of more than 200. But Globeville went from 864 children in the 2010 study to 1,013 in 2015.

Within this total, there were plenty of shifts. Astonishingly, the 2010 analysis located not a single African-American child living in Globeville, but by the 2015 study, 96 were living in Globeville during a period when the total number of kids in this category in Five Points was cut by well over 50 percent.

In another nascent gentrification hint, kids defined as “non-Hispanic white” also experienced a relative boom in Globeville – from 22 to 196. Meanwhile, there were fall-offs among youths deemed “not non-Hispanic white” (842 to 817), “some other race or two or more races” (361 to 172) and “Hispanic or Latino” (842 to 685).

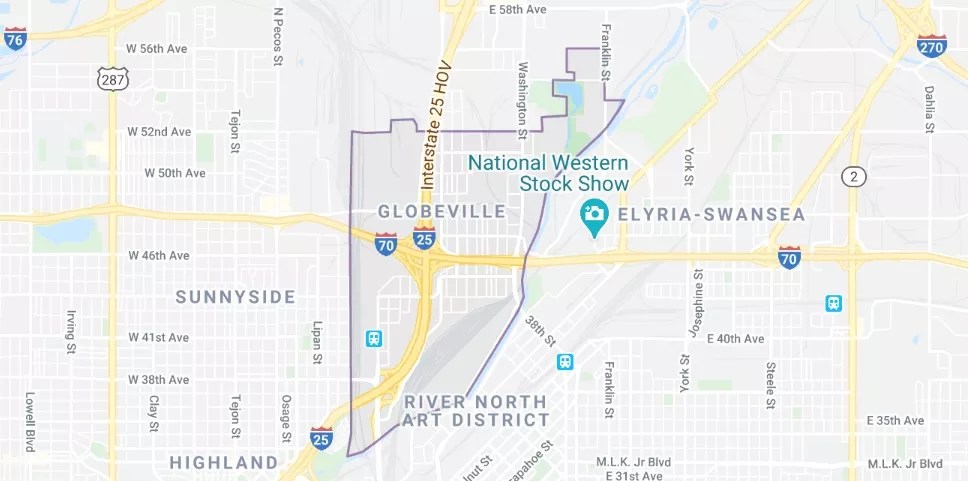

A map of the Globeville neighborhood.

Google Maps

Economics

Researcher Noelke cautions against automatically assuming that there’s a causal relationship between gentrification and the data he and his crew assembled. “Without further information, it is not clear what is driving this change,” he notes. But themes that arise certainly don’t preclude this prospect.

Consider single-headed households, which stood at 41.2 percent in 2010 and 57.2 percent in 2015. Five Points also saw an increase in this metric, perhaps because more families departed and were replaced by young singles who chose to rent in newly developed apartment complexes rather than buying a pre-existing home, the sales of which dipped by a substantial margin. That’s a less likely explanation for Globeville, where the home ownership rate actually bumped up from 39.4 percent to 41.4 percent. (Mirroring these figures is a slide of the housing vacancy rate from 11.2 percent to 7.1 percent.) In this case, then, single-headed households could be individual parents with children who had to leave Five Points, Cole and Whittier because of the expense.

One other apparent contradiction: The poverty rate went down (36.6 percent in 2010, 33.9 percent in 2015) while the public-assistance rate climbed several notches (22.3 percent to 27.9 percent). But both median household income and high-skill employment remained worrisome, and much lower than in Five Points, Cole and Whittier; they each moved in the gentrification direction: $25,356 to $39,808, and 11.4 percent to 19.2 percent. The same can be said of the employment rate (59.7 percent to 67.9 percent) and health-insurance coverage (70.0 percent to 81.8 percent).

Education

The goal of the Child Opportunity Index 2.0 was to draw attention to educational roadblocks for children in communities just like Globeville. School poverty, measured by the percentage of students in elementary school eligible for free or reduced-price lunches, scooted up from 93.1 percent in the 2010 survey to 93.5 percent five years later – not exactly progress. Likewise, math and reading proficiency for third-graders slipped from one report to the next.

In contrast, adult educational attainment – the percentage of adults 25 or older with a college degree – more than doubled (7.2 percent to 15.4 percent). Moreover, the high school graduation rate took a considerable leap (60.0 percent to 78.5 percent), as did early childhood education enrollment (37.5 percent to 45.9 percent). And the number of high-quality early-education centers – the types of facilities that tend to follow the money – rose by nearly 50 percent.

This last batch of findings looks like a glimpse of gentrification to come.