Jay Vollmar

Audio By Carbonatix

When Bart Berger, a fourth-generation Coloradan, was living on Soda Creek Road in Jefferson County, he had to drive by Fillius Park, a Denver Mountain Park, every day to get into Evergreen. One day, he stopped by the park 23 miles west of Denver off the Evergreen Parkway, and the avid historian and open-space advocate was dismayed by what he saw. “The park was a mess,” he recalls. “It got my attention because the shelter was so raggedy. I couldn’t understand why a shelter that was that architecturally interesting would have been so unattended and decrepit.”

The deteriorating condition of Fillius Park prompted Berger, then a member of Denver’s Landmark Preservation Commission, to look into the history of Denver Mountain Parks. “I thought I was savvy about Denver – I can recite the street names from Simms to Yosemite in order,” he says. “My ignorance surprised and intrigued me.”

He toured the more than twenty parks in the century-old Denver Mountain Parks system and commissioned an architectural review of the historic structures within them. “I was shocked to find out how many there were and how far they were spread out,” he says.

But he learned a lot more than that as he launched the Denver Mountain Parks Foundation, a nonprofit designed to support – and perhaps even save – Denver Mountain Parks. Its efforts got a big boost from Denver City Council on April 30, when members approved spending $700,000 on a project at the most famous mountain park of all: Red Rocks.

Bart Berger was dismayed by what he found at Fillius Park fifteen years ago.

Anthony Camera

“Denver is a pretty city, I grant you, but people who come here from the Atlantic Seaboard and from the prairies of the Middle West do not come to look at handsome buildings,” John Brisben Walker said – not today, when so many of the new buildings in Denver are far from handsome, but back in 1910. “They come here to see the marvelous mountain scenery they have heard and read so much about. And when they get here, they find so many difficulties in the way of reaching this scenery that they quickly become discouraged and rush off to Colorado Springs or somewhere else, where the people have improved the splendid gifts nature has placed within their reach.”

A wealthy and charismatic entrepreneur known for his ambitious ventures, Walker enlisted two cohorts, Kingsley Pence and Warwick Downing, and rallied support to establish municipal parks in the mountains. In 1912, Denver voters approved a dedicated 0.5 mill levy to buy open space and create Denver Mountain Parks. By 1914, Boston-based landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. was creating a system that ultimately stretched from the foothills of Jefferson and Douglas counties to the mountains of Clear Creek and Grand counties, studded by structures designed by such renowned architects as Burnham Hoyt.

Within three decades, Denver Mountain Parks had reached its current size: 22 developed parks and 24 conservation areas totaling more than 23 square miles of land spread over four counties – all outside the Denver city limits. The system ranges over five life zones, from close to the peak of Mount Evans (with a 10,000-year-old fen and plants found nowhere else outside of the Arctic Circle) to the oak woodlands of Daniels Park in Douglas County. Even the bison that roam Daniels and Genesee Park, the largest in the system at 2,413 acres, are unusual: Their lineage traces back to the last herd in Yellowstone National Park.

Civic Center Park: Part of the City Beautiful vision for Denver.

Civic Center Park Facebook

Historic Denver Executive Director Annie Levinsky describes the creation of Denver Mountain Parks as part of a three-legged stool supporting Mayor Robert Speer’s City Beautiful Movement. One leg was Civic Center Park in downtown Denver, the heart of his vision. Parks and pathways connecting neighborhoods made up the second leg. The third leg was Denver Mountain Parks, designed to provide respite to all Denver residents. “There was nothing more influential for Denver than that City Beautiful vision,” Levinsky says. “Through great civic design and great community spaces like parks, we could be a successful city.”

If the city hadn’t taken action a century ago, much of the land that is now part of Denver Mountain Parks would have been developed. “The Denver reach was pretty far when it came to preserving open space and parkland in the early days,” says Denver Mountain Parks planner Brad Eckert. “Think about the value of those properties today just in terms of the dollar.”

The value of many of those properties got a big boost during the Depression, when Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Civilian Conservation Corps, a move designed not only to produce jobs, but to protect public land and properties around the country, by putting young men to work on public projects there. Corps members received housing, three meals a day and $30 a month – $25 of which went directly to their families.

One of the CCC’s most important projects was turning an incredible rock formation just outside of Denver into an actual amphitheater. Walker, who owned the property, had produced a number of concerts there on a makeshift stage between 1906 and 1910. In 1928, George Cranmer, a stockbroker who would be named Denver’s Manager of Parks and Improvements by Mayor Ben Stapleton, persuaded the city to buy 728 acres from Walker for $54,133; it was officially renamed Red Rocks.

The Civilian Conservation Corps came to Red Rocks.

Denver Public Library

With Cranmer in the lead, in 1935 the CCC took on the task of creating Red Rocks Amphitheatre, housing workers at Mount Morrison, a CCC camp created at the park with five barracks as well as support buildings.

Red Rocks was formally dedicated on June 15, 1941.

At the same time that he was pushing Red Rocks, Cranmer had another major project in the works: a mountain park that would become a winter sports center comparable to European resorts. He negotiated a deal with the U.S. Forest Service for the use of 6,400 acres at the West Portal of the Moffat Tunnel, raised money and enlisted volunteers to clear the slopes, and built the first rope tow. Denver acquired 89 acres for the ski-resort base, and in January 1940, 10,000 people attended the grand opening of Winter Park.

Fifteen years later, Denver City Council retired the mill levy that had been passed to support the parks, and the Mountain Park Board that had provided oversight was disbanded. Denver Mountain Parks became just another maintenance district in the Denver Department of Parks and Recreation, competing for money and attention with other projects across the city.

As funding declined, so did the condition of the parks. The situation had become so dire that after seeing the deterioration at Fillius, Berger formed the Denver Mountain Parks Foundation in 2004. Over the past fourteen years, he’s been a constant champion of the parks, raising more than $500,000 from a handful of donors to pay for restoration projects.

The base of Winter Park Resort started as a Denver Mountain Park.

Winter Park Resorts

Before World War II, the rationale behind Denver Mountain Parks was valid, Berger says. People would hop in their cars and take a scenic drive to one of the parks, where they would have a picnic and relax with family and friends. But after the war, people started hopping over the mountain parks in favor of destinations that offered more difficult hiking and skiing. “The mountain parks don’t compete at the same level for tourist dollars,” he notes.

Today, one-third of the mountain parks’ users are residents of the counties where they’re located; another third come from Denver; and the remainder come from outside of Colorado, including some international visitors. Because the parks aren’t located within any Denver City Council district, no single councilmember is responsible for advocating for their care.

“The mountain parks are out of sight, out of mind,” Berger explains. “I realized the mountain parks did not have a voice. Denver mountain parks were popular in the early days of the twentieth century but lost funding in 1955. They had to compete for funding with city parks. I started the foundation to advocate for the mountain parks and raise money.”

The Denver Mountain Parks system includes historic structures.

Anthony Camera

In addition to holding fundraisers and collecting donations, Berger organized writers and photographers to collaborate on Denver Mountain Parks: 100 Years of the Magnificent Dream, a 2013 book written by Wendy Rex-Atzet, Sally L. White and Erika D. Walker, with photography by John Fielder.

“For a century,” Berger wrote in the afterword, “these places have been well loved, if not loved well, by Denver taxpayers, locals and neophytes; by mayors and city councils; by citizens and visitors to the Mile High City.

“Most important, I learned that these places do not thrive without citizen involvement. Without that, elected officials will prioritize urban concerns. Too long have the Denver Mountain Parks been in sight and out of mind. We can no longer be spectators.”

At the same time that Berger was creating the Denver Mountain Parks Foundation, local governments were realizing that the parks needed help. In 2002, Jefferson County Open Space and the Denver Department of Parks and Recreation worked together to develop a comprehensive planning strategy, hiring the landscape architecture firm of Mundus Bishop to come up with a vision for the future of the mountain park system that included everything from design guidelines for shelters, buildings and park features to the creation of new trails, overlooks and amenities, as well as protective measures for the parks.

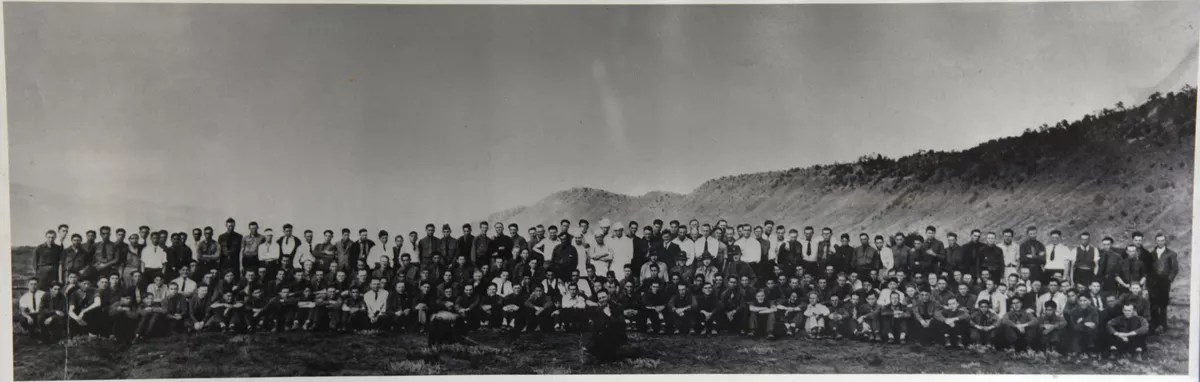

A CCC crew in Colorado.

Denver Public Library

Because the parks are spread across four counties, a regional approach is key to implementing the long-term vision, according to Mundus Bishop.

“Jefferson County Open Space and Denver Parks and Recreation Department both recognize that outdoor recreation plays a vital role in the quality of life for metro-area residents, and they understand that the unique lands they manage offer significant benefits to their constituents and to regional users,” the 2002 Denver Mountain Parks and Jefferson County Open Space Management Plan states. “The ties that bind the agencies are many. Each owns public lands within Jefferson County. Both are committed to protecting and enhancing the natural, cultural, historic and scenic resources of their lands, while providing recreational access that is consistent with their resource values. In many instances, Jefferson County lands abut those owned by the City & County of Denver. The same users hike these lands without recognizing that there are separate owners.”

In 2006, then-mayor John Hickenlooper asked a cross-section of regional leaders to evaluate the management, funding and future of the Denver Mountain Parks system. The result was the 2008 Denver Mountain Parks Master Plan, which assessed the value of the parks to Denver residents. Surveys performed at the time showed that 68 percent of Denver residents visited a typical Denver Mountain Park (excluding Red Rocks and Winter Park) a least once a year. Altogether, the mountain parks system saw more than two million visitors a year.

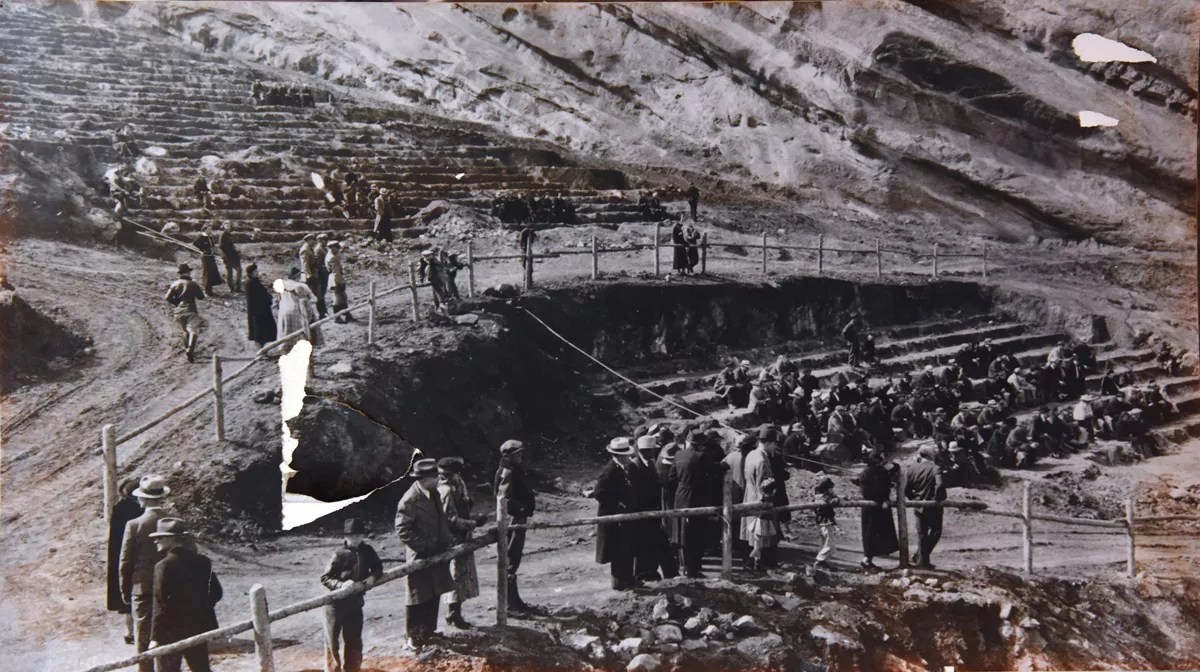

CCC crew working on Red Rocks.

Denver Public Library

The master plan’s key recommendations included:

•Increasing awareness of the mountain parks and improving the visitors’ experience through communication and marketing materials.

•Increasing the mountain parks’ share of the yearly capital budget, with a minimal $1 million share of the annual Capital Improvement Fund and increasing operating funds when supported by the economy.

•Building on the entertainment and entrepreneurial opportunities in the system at places such as Red Rocks, the concessions in historic lodges or Winter Park.

•Building a Mountain Parks Division within Parks and Recreation when feasible to increase awareness, visibility and ability to focus on the complexity and regional nature of the system.

•Creating Natural Resource Management Plans for each park to develop site-specific strategies for natural resource restoration and protection, recreation and volunteerism.

•Creating and adopting the Denver Mountain Parks Design Guidelines to protect and build on the character and legacy of the system’s designed buildings, structures and landscapes.

Park planner Brad Eckert at the Mount Morrison CCC camp.

Anthony Camera

While parks planner Eckert acknowledges that there is still work to be done, he says that many of the recommendations in that master plan have been implemented. The funding for mountain parks has increased over the past ten years, as has the focus on creating awareness through youth programs that connect kids to nature.

“We partner with the zoo to get kids out to the parks and do research on bison,” Eckert says. “We’ve built new trailheads, parking lots, new restrooms. We’ve printed maps and installed informational kiosks at the trailheads.”

Anthony Camera

But the biggest push for the parks is coming from a partnership between the Denver Department of Parks and Recreation and HistoriCorps, a national historic-preservation nonprofit based in Denver.

And not just in Denver anymore: HistoriCorps is about to move its headquarters to the Mount Morrison Civilian Conservation Corps camp, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1990. In exchange, HistoriCorps has signed on to restore the CCC buildings at the camp and will work with young adults, teaching them the skills to do the work. “We want to build on the legacy of the CCC, where they teach skills like masonry and carpentry,” Eckert says. “The avenue to learn those skills would be the restoration of our historic structures.”

On April 30, Denver City Council agreed to spend $700,000 to renovate one of the camp’s barracks for use as an office building and storage space for the tools that HistoriCorps uses on its restoration projects. HistoriCorps will also be allowed to store its trucks and heavy equipment at the camp. “It will be a campus at the CCC where youth and other folks can come and stay and spend a week learning masonry and other skills,” Eckert says. “They’ll take those skills and then go on to do whatever it is they want to do with them.”

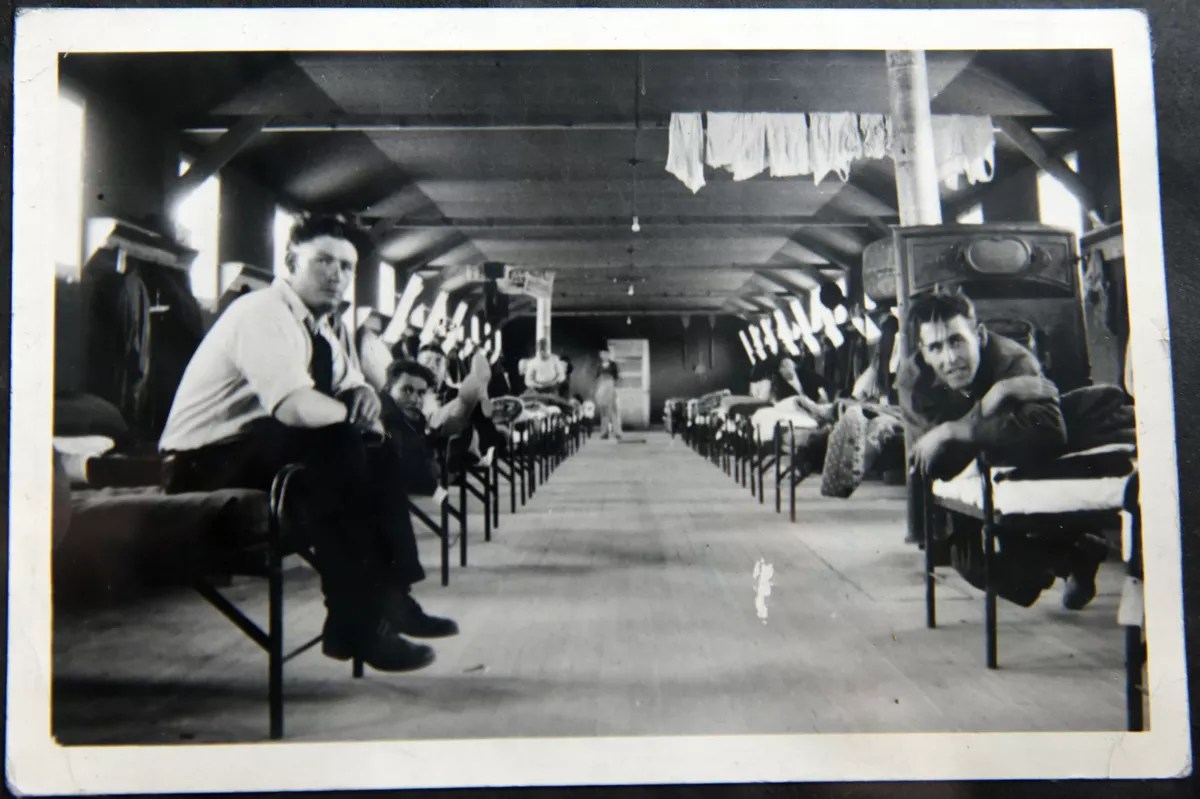

CCC workers would gather in this hall at Mount Morrison.

Anthony Camera

But HistoriCorps is about more than sharing skills. The nonprofit evolved out of a network of volunteers and professionals dedicated to saving America’s special places, starting in Colorado. Between 2002 and 2007, a group representing land managers and preservation stewards worked together to restore buildings in the Pike-San Isabel National Forests, Leadville and Twin Lakes. The partnership demonstrated that a public-private program engaging a network of volunteers and professionals in the preservation of historic places was feasible.

In 2009, the U.S. Forest Service approached Colorado Preservation Inc. with the idea of forming a “corps” modeled after community-service programs like the CCC.

HistoriCorps was created through an appropriation of funding by the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. The first official HistoriCorps preservation project was a community work day in October 2009 that involved painting, cleaning and repairing a Forest Service ranger station and the facades of historic buildings along Main Street in Saguache. The project had thirty volunteers from the community.

A restored bunkhouse at Mount Morrison.

Anthony Camera

Since then, HistoriCorps has completed more than 200 projects in 25 states. Through its Program in Heritage Conservation and Construction, students learn the decision-making and hands-on skills necessary to successfully complete a preservation project on time, on budget and with the quality that historic places deserve. All of the work is done in compliance with the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties; HistoriCorps’ biggest client is the Forest Service.

Denver’s arrangement with HistoriCorps has been nearly two years in the making. In the fall of 2016, Mayor Michael Hancock said he’d like to see the CCC camp put to use. “Mayor Hancock wanted to see it repurposed and occupied and used again,” HistoriCorps Executive Director Towny Anderson recalls. “There’s an old adage: Historic buildings, when they’re occupied, they’re taken care of. When they’re not occupied, they tend to deteriorate, and that deterioration accelerates.”

Funding for the work at the CCC camp and other mountain parks is coming from the $2 million that Denver Mountain Parks received in the GO Bonds passed by voters in 2017, as well as the Denver Mountain Parks Foundation.

Art created by a CCC worker.

Anthony Camera

Historically, Denver’s funding for the mountain parks is about one-third what other counties and cities spend on their open space and mountain systems, according to the 2008 Denver Mountain Parks Master Plan. While Denver Mountain Parks account for 72 percent of the acreage in the city’s park system, just 1.3 percent of the 2018 Denver Parks and Recreation budget, or $950,990 out of $70.8 million, is devoted to them. The backlog of work needed at the parks, including road improvements and shoring up structures, will cost about $30 million, noted Tina Bishop, principal at Mundus Bishop, at this year’s Colorado Preservation Inc. Saving Places Conference.

Two mountain parks – Red Rocks and Winter Park – generate revenue, but not all of that money finds its way back into the Denver Mountain Parks system. Alterra Mountain Company, the new incarnation of Intrawest after it was acquired by KSL Capital and Aspen Skiing Co., pays the city $2 million a year plus 3 percent of gross revenue over $33 million to operate Winter Park. That money is distributed among Parks and Recreation projects scattered throughout the city; in the past few years, some of it has gone to improvements at Genesee Park.

A restored barracks at Mount Morrison.

Anthony Camera

Denver Arts & Venues collects the revenue generated at Red Rocks, which in 2016 totaled $31.2 million, according to a city audit. Denver Mountain Parks gets some of that money, which has gone to hiring additional rangers to patrol Red Rocks to keep people from climbing on the rocks. It’s also been used for trail and restoration projects at Red Rocks.

“We’d like to see a little bit more, but the council allocates where it goes,” Eckert says. “There has been some movement to try to get the mountain parks looking at some sustainable and dedicated funding sources.”

In addition to the work at Mount Morrison, HistoriCorps volunteers will restore iconic structures in four more Denver Mountain Parks this summer: Little Park, O’Fallon Park, Bergen Park and Fillius Park.

A CCC work crew at Camp Morrison.

Denver Public Library

Denver acquired the 400-acre Little Park, named after land donor C.W. Little, in 1917. Located north of Mount Falcon at the west edge of Idledale, Little Park was among the first of the city’s mountain parks and offers hiking, biking and fishing access along Bear Creek. Work on the Little Park Wellhouse, widely considered to have been designed by noted Colorado architect J.J.B. Benedict, is just about complete. “The well house used to have a cupola that acted as a ventilator, and we’re reconstructing that,” Anderson says.

Next will come restoration of the four-sided chimney at O’Fallon Park, which features three fireplaces.

Volunteers will work with field staff to reinstall and replace loose or broken brick, stone and flagstone; stabilize and rebuild brick hearths; repoint missing and deteriorated mortar; and repair and reinstall sandstone benches and corbels. The 860-acre O’Fallon Park was donated to Denver in 1930 by Martin J. O’Fallon for “the use and pleasure of the people.” O’Fallon’s wishes for the park are inscribed on a plaque on the chimney. O’Fallon is the largest park in the Corwina-Pence-O’Fallon park district, three contiguous parks acquired between 1914 and 1938. The district was added to the National Register of Historic Places just after Christmas 1990.

Fillius Park in the early days.

Denver Public Library

Work on the well houses at Bergen and Fillius parks is scheduled for three weeks beginning July 11. Created on land donated by Oscar Johnson in 1915, Bergen Park is one of the most-visited parks in the Denver Mountain Parks system. The well house there will be re-roofed and repointed; masonry and carpentry work will also be done to restore and repair the windows and doors. The park also has a stone shelter designed by Benedict and built in 1917; a small monument commemorating early settler Thomas C. Bergen is on the east section of the park, and a historic stone restroom, no longer in use, is south of the monument.

Denver acquired the 108-acre Fillius Park, named for Denver Park Board member Jacob Fillius, in 1914. There’s another Benedict-designed shelter here, with openings in its north facade oriented toward the Continental Divide. The shelter’s detail makes it one of the most important structures in the mountain parks system. The Fillius Park well house will be re-roofed and its log walls repaired.

Next year, HistoriCorps’ work will focus on Daniels Park, Katherine Craig Park, Starbuck Park and a shelter on Lookout Mountain. “A place really doesn’t become a place until it’s defined by a historic structure,” says Anderson.

The Mount Morrison CCC camp museum is open for visits.

Anthony Camera

Restoring Denver Mountain Parks not only preserves a critical piece of the Mile High City’s history; it also provides educational opportunities that aren’t available anywhere else. On Lookout Mountain, visitors can study the history of the West at the Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave. They can learn about geology as well as listen to music at Red Rocks. At the Mount Morrison CCC camp, they can visit the recreation and mess halls by appointment and wander around the grounds during daylight hours, discovering the story behind the Civilian Conservation Corps.

“The ability for the City of Denver to use that resource for the education of citizens is unequaled,” Berger says.

“The Denver Mountain Parks are a resource that can uniquely educate children about nature. You can take a kid who’s learning about animal husbandry and teach him about bison. The mountain parks are an integral part of life in the city.”