Sheila Sund at Flickr

Audio By Carbonatix

Every day, all across Denver, we’re wrecking the planet – and we’re doing it in ways that almost none of us ever think about.

Every time we start up a car or flick on a light switch, we’re contributing to the emission of heat-trapping gases that are causing the world’s climate to warm to dangerous levels. But those are the obvious things, the things most of us are at least dimly aware of. Just as important are the emissions sources that often go overlooked: the boilers that heat our showers in the morning; the methane released by decomposing trash in our landfills; the cement poured into the foundation of every new building added to Denver’s rapidly growing skyline.

Climate change is a global problem, but many of the actions required to solve it will need to be taken at the local level. Scientists warn that we have just eleven years to cut global greenhouse gas emissions nearly in half – and more than 70 percent of those emissions come from the world’s cities.

“Cities will need to roll up their sleeves and actively build and invest in the infrastructure and incentives needed to make significant progress,” wrote the authors of a 2017 report released by C40 Cities, a global coalition of city governments committed to confronting climate change. “They cannot do it alone, but they can lead the way, and they must act today.”

Like other major U.S. cities, Denver has made important strides in some areas of climate policy: emissions from electricity use, for example, are down roughly 18 percent from their 2007 peak, according to city data. Those emissions are set to decline further over the next decade as Xcel Energy, Denver’s electric utility, continues to invest in renewable energy and retire many of its dirtiest coal-fired power plants. Xcel has pledged to achieve an 80 percent cut in carbon emissions from electricity generation by 2030, which will go a long way toward meeting the city’s goal of a 100 percent renewable grid.

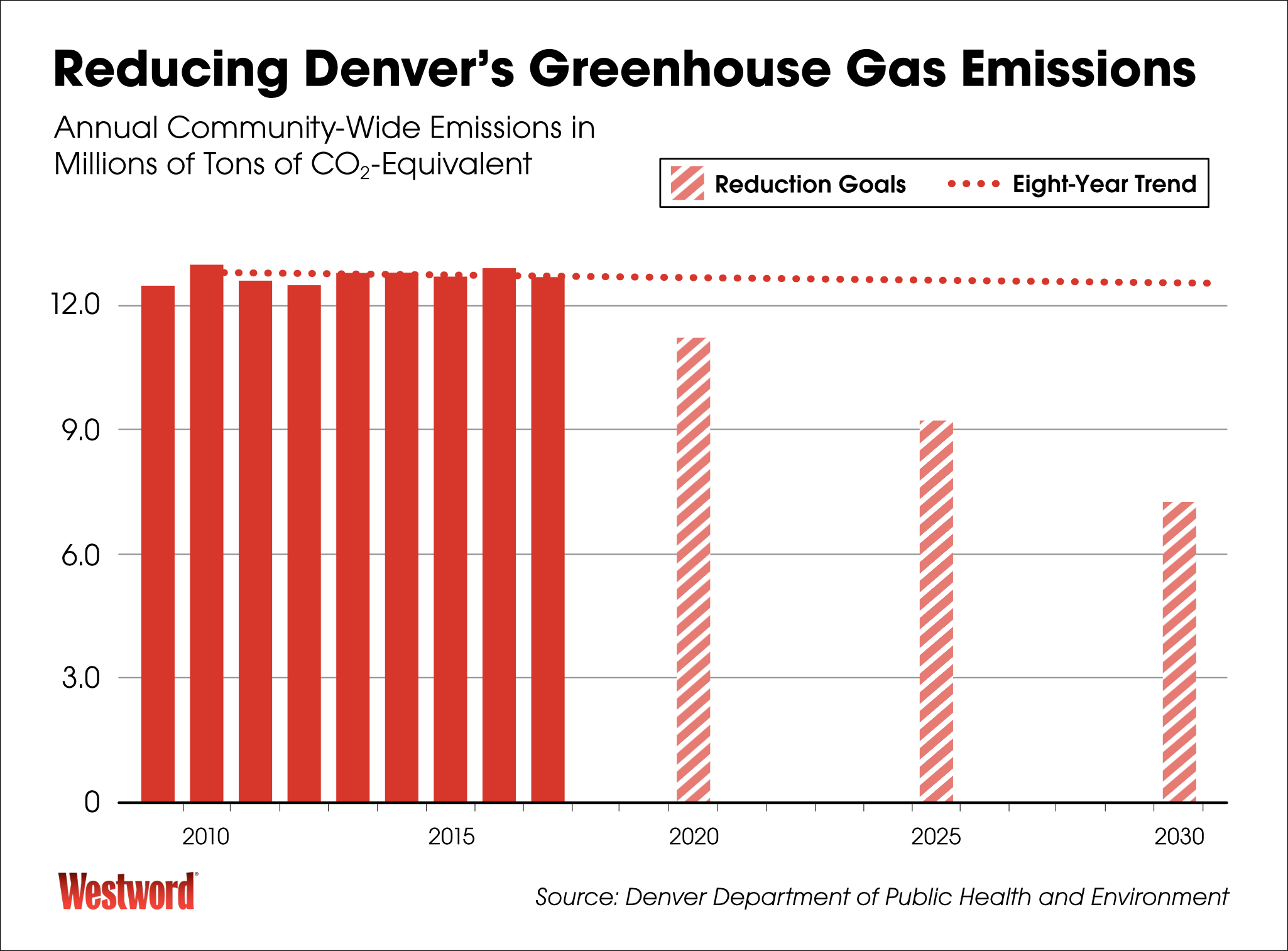

In other areas, however, Denver’s progress in reducing emissions remains slow, stalled, or worse. City data shows that after declining slightly during the Great Recession, emissions from transportation have been on an upward trend since 2009. Emissions from the heating sector are down slightly – but that’s largely because warmer winters in recent years have reduced natural gas consumption, a city analysis shows. Overall, Denver’s emissions have remained roughly flat since 2012, with small cuts and efficiency gains offset by the city’s continued economic and population growth.

Stopping climate change, experts say, isn’t possible through market solutions or shifts in consumption habits alone – it will take robust, focused policy intervention from governments around the world. Many advocates for strong climate action compare the scale and urgency of the effort required to the U.S. economy’s mobilization during World War II.

“I don’t think that most politicians, or the public, have fully comprehended what the science is saying yet,” says Micah Parkin, executive director of the climate activist group 350 Colorado. “It’s a growing number, which is why we’re starting to see these loud calls for action. But I don’t think the majority of leaders have followed the science carefully enough to see that we need a major transition to renewable energy within the next eleven years.”

When top scientists with the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued a landmark report last year, outlining the dire consequences of allowing the planet to warm by more than 1.5 degrees Celsius, they urged leaders around the world to make “rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society.”

Here in Denver, critics of Mayor Michael Hancock’s administration don’t believe the changes made by the city have been rapid or far-reaching enough.

“I do think that the administration has been quite beholden to the business community and developer interests,” says Jamie Giellis, a former president of the River North Art District who is challenging Hancock in May’s mayoral election. “Any time you’re talking about sustainability issues relating to development, design, the impacts on the cost of a building, you’re going to get pushback from [developers]. And too often the city has given in to developer concerns, more than community concerns.”

Though the figure can vary slightly depending on the methodology used, the City of Denver estimates its annual emissions at between 12 and 13 million metric tons of carbon-dioxide equivalent (CO2e), a metric used to compare the warming effects of various greenhouse gases. The city’s emissions have hovered within that range for much of the last decade. If Denver is to meet its own emissions goals, that will need to change quickly.

In July 2018, the Hancock administration released a “Climate Action Plan” that commits Denver to achieving an 80 percent cut in citywide carbon emissions by 2050. That’s less ambitious than the IPCC recommendation of net-zero emissions by the same date – but the plan’s shorter-term goals are more closely aligned with the IPCC’s timeline, including a 45 percent reduction in overall emissions by 2030.

“Interim goals are imperative in order for us to track progress and continually reassess methodologies,” Hancock said at the time of the plan’s release. “A variety of approaches are needed to reach the long-term objectives, and the City will lead the way in achieving meaningful strides toward these critical goals.”

But less than a year after the plan was released, Denver appears on track to fall short of its first major target: to reduce total emissions to 15 percent below 2005 levels by the end of next year. Barring a sharp, sudden decline in emissions starting this year – or in 2018, for which a greenhouse gas inventory hasn’t yet been released – the city won’t meet that goal.

Westword

One of the primary culprits behind the lack of progress is Denver’s failure to reduce emissions from the transportation sector, which rose by nearly nine percent between 2012 and 2015, according to city data. As part of its 2020 Sustainability Goals, Hancock’s administration set a goal of reducing trips made in single-occupant vehicles to under 60 percent. But the most recent data available shows that figure stuck near 70 percent.

“We’re seeing that, in large part, because we don’t have a localized transit network that serves Denver,” says Giellis. “We have a regional spine in FasTracks, but once you get off that regional spine, you largely have to get into some sort of vehicle to get to your next stop.”

Even as car-centric projects like the I-70 expansion have received support and funding from city and state leaders, Denver has lagged behind in encouraging residents to use alternative modes of transportation. The number of Denverites using public transit in their commute has barely budged, from 5 percent to 6 percent, since the passage of FasTracks in 2004. The Hancock administration has made investment in transit a major component of its Denveright master plan, which is expected to be finalized before May’s municipal election – but many of its expected impacts are years, or even decades, away. A spokesperson for Hancock did not return a request for comment on his priorities for public transit and other emissions-reduction goals.

“Where are we with transit?” Giellis says. “In the last five to ten years, as the city has gotten extremely wealthy off of property and sales taxes, haven’t we started building it? Why are we still just talking about planning it? There’s just no leadership.”

Over half of Denver’s greenhouse gas emissions come from building energy use, a broad category that includes some of the lowest-hanging fruit in climate policy – and some of the most daunting long-term challenges.

Deep cuts into emissions from the electric sector are likely to be made in cities all around the world in coming years, and Denver is no exception. Thanks in large part to subsidies and other public investments made over the last two decades, new wind and solar generating capacity is cheaper to build than ever, and utilities like Xcel are investing aggressively in a transition to renewable sources. If Xcel fulfills its pledge to achieve an 80 percent emissions cut in electricity generation by 2030, the carbon savings would account for more than half of Hancock’s 2030 climate goals.

But about a third of Denver’s building emissions come from natural-gas-powered heating, according to city data, and reducing these heating-sector emissions is a much taller order. In the short term, efficiency gains – such as retrofitting building envelopes to better retain heat – can help result in modest reductions. But over the next several decades, in order to achieve the so-called “deep decarbonization” needed to bring global warming to a halt, cities will have to transition away from gas-powered heating entirely. The heating systems of tens of thousands of Denver buildings will need to be electrified, or converted to use technologies like solar thermal or geothermal heating.

“Reducing energy use and emissions from buildings will not be easy,” wrote the authors of the 2017 C40 Cities report. “It will require significantly more focused effort than most cities have currently undertaken.”

Because cities are generally responsible for setting standards for new and existing buildings through their municipal codes, building emissions are one of the policy areas in which they can have the most direct impact on climate action. Across the country, local governments are beginning to take more aggressive steps to address emissions from the heating sector; just up the road in Boulder, the city has launched an ambitious electrification initiative with the goal of reducing residential consumption of natural gas 85 percent by 2050. And a landmark bill passed last year by Washington, D.C.’s city council created a special task force to implement standards that will achieve a 50 percent cut in citywide natural-gas consumption by 2032.

One of Denver’s highest-profile brushes with clean-energy policy, however, illustrated the challenges of tackling building standards in a high-growth city where developers wield so much influence. Despite opposition from Hancock and other civic leaders, voters in 2017 passed a citizen-led ballot measure known as the Green Roof Initiative, requiring developers to incorporate rooftop gardens or solar panels in the construction of all new buildings larger than 25,000 square feet. But within a year of its passage, City Council repealed the measure and replaced it with a less disruptive “cool roof” ordinance.

“As a city, every time we sort of get bold, we then pull back,” says Giellis, who supports strengthening the cool-roof measure to more closely match what voters passed in 2017. “The voters were willing to be bold. If we don’t follow through with that intent, are we doing ourselves and our community a disservice? I think we are.”

Rooftop gardens alone, of course, won’t solve the climate crisis. That will take a concerted effort across multiple sectors and areas of public policy, including often-overlooked emissions sources like materials production, food consumption, and waste management. These efforts will have to be undertaken all around the world, but much of the necessary work will have to be done in and around major cities like Denver.

“I think we’re at a point now where we’re going to have to make some massive investments,” says Giellis. “Transit, all of our infrastructure projects in the city being built sustainably, introducing a solar economy, incentivizing the use of electric vehicles, increasing recycling rates. Those are all moves that are totally local, and things we could start focusing on really quickly.”

The stakes, for Denver and the world, are high. Human activity has already caused Colorado to warm significantly, leading to hotter summers, extreme drought and increased wildfire risks; if those trends continue, Denver is projected to experience a higher frequency of extreme weather events, increased water scarcity due to a shrinking snowpack, and unhealthier levels of ozone due to warmer temperatures. Around the world, exceeding the IPCC’s 1.5°C warming limit would put hundreds of millions of people at greater risk of natural disasters and political destabilization.

“It does feel like momentum is building,” says Parkin. “Sadly, with all of the horrific climate-induced catastrophes that have been happening – stronger hurricanes, increased drought, the wildfires that have happened here – it seems like people are really waking up to how much of a precarious situation we’re in with the climate crisis, and demanding action.”

Environmental groups will hold a Mayoral Candidate Forum focused on sustainability issues at 6 p.m. tonight, March 21, at The Alliance Center in downtown Denver. Tickets are available here.