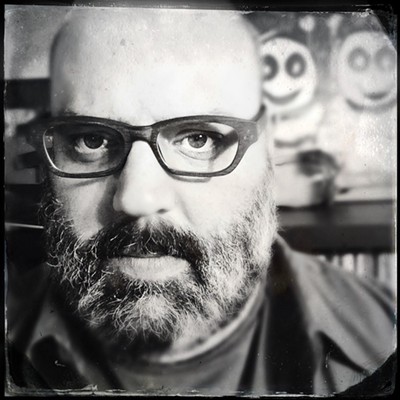

Early in his career, pianist Uri Caine got to play with jazz legends like Philly Joe Jones and Hank Mobley. While Caine is a deft improviser and can play the hell out of bop, he's incredibly multi-faceted and also quite equally at home playing avant-garde, classical (Caine's released a number albums of forward-thinking arrangements of Mahler, Wagner, Beethoven, Bach and Schumann), klezmer and a number of other genres.

See also: - Friday: Uri Caine Trio at Dazzle, 1/11/13 - The five best jazz shows in Denver this month - Ten essential jazz albums if you know squat about jazz

With the Philadelphia Experiment, he collaborated with bassist Christian McBride and Roots drummer Questlove, and with his Bedrock Trio, Caine explores jungle and drum and bass. In advance of this show this Friday at Dazzle with his jazz trio, which includes bassist Drew Gress and drummer Clarence Penn, we spoke with Caine about studying with Bernard Peiffer and George Crumb and playing classical and jazz.

Westword: With you having hands in various worlds, especially jazz and classical, do you look at them in different ways, or is it all music to you?

Uri Caine: Honestly, both, because it is all music, and it is all part of a bigger thing, especially if you think of it as a spectrum. There are certain worlds. There are certain traditions. There's different expectations even within supposedly the same world. There are a lot of different worlds. As a musician, you're really into more of the practical aspect of how to pull the whole thing together and make it work.

But in terms of various experiences that I've had... Let's say dealing musicians who are mostly improvisers, musicians that only read music, musicians that are coming out of different schools -- I mean, not literally the academic schools but different ways of thinking -- depending on how we grew up, we're all products of that, too.

Again, it's about how to integrate all that. I have learned that if you're playing with certain people that if you, lets say, write too much, it might not work as well, but with other people, it does work well. So, it's just a question of who you're playing with and the type of things that you're trying to have happen in music.

Did you play classical before you started playing jazz?

I started out as a little kid playing easy, simple classical music, just really easy piano music. But I grew up in Philadelphia, and I went to hear a lot of the musicians who were playing. Philly had a really good scene, and I met a teacher named Bernard Peiffer, who was actually from France but he had settled Philadelphia, and he was teaching a lot of the young musicians. He completely turned my head around. I was about twelve years when I started studying with him.

That, to me, was a real turning point when I look back on it because I started to get really... I mean, he was coming at me from a lot of different ways about things you have to get together as a musician. I was trying to please him. I was also starting to play musicians around Philadelphia who were my own age and older musicians who were legends to us, but you could actually play with Philly Joe Jones.

It wasn't something that I thought, "Oh, I'm going to do this." But one of the things that Peiffer was really into was -- he said to me, "If you're already studying Mozart and Bach, and you can use that to, first of all, get better technique but also the ideas that are happening and the chords that are happening." I mean, think of it that way. It sort of made sense to me. So I did start to practice in a certain way, as well as doing things like composing my own tunes and learning tunes and things about harmony and checking out a lot of music. That whole thing. I got into that, and so that became my world.

Later on, you studied with George Crumb. What did you come away from that experience in studying with him?

You know, it was interesting. I actually started to study with this other composer in Philadelphia who taught at the University of Pennsylvania, and I got a whole other way of dealing with music. By the time I got to college, which is where I met George Crumb, he was a very, gentle, sweet, shy man, but he loved to play four-hand piano music. He was a good pianist, so a lot of the time, he would look at my pieces for about ten minutes and say, "Oh gosh, that's really good." And then, it's like, "Okay, lets start playing," and he would whip out the music, and we would have a good time.

He was unlike a lot of the other teachers that encountered in the university or people that are much more... they have program. He was extremely gentle. And, of course, I love his music. I was influenced a lot by hearing live performances of his music around Philadelphia and some of the records like Ancient Voices of Children that came out on Nonesuch. That was a turning point for me. You know how a lot of musical turning points are just hearing different things, and, "Wow!" Everything from Cecil Taylor to the Philadelphia Orchestra to all these musicians who came through Philly.

Was Cecil instrumental in getting you into more avant-garde stuff?

It's interesting because the first time I saw him was... There was a series at a church in Philly that was just incredible. But I had heard a lot of that type of music in a different way, from composers like George Rochberg, and going to hear music where people were playing music like Boulez, just that world of playing piano in a different way. So, of course, I was influenced by that.

With some of your classical albums, you've taken liberties, like with the Goldberg Variations. Have you ever gotten any flack from the classical purists?

Sure. I mean, I have to say that the response, in general, has been, "We don't like this but who cares," or, "We like this." I still do Mahler and a lot of different Goldberg Variations. Coming up next year, I have a group that plays that. Obviously it depends on what people are expecting because for a lot of people these pieces are iconic pieces where you don't change a note. On the other hand, there are a lot of people that know that music and are open to something like that. As with everything, you get all types of reactions.

I would assume the classical seeps into jazz playing and your jazz compositions. Would you agree?

I would say it [does] only in the sense that it's all part of a piece. Sometimes I'm trying to go for different things because the process of creating is different. A lot times, maybe if I'm playing with my own trio at Dazzle, if we're playing standards, we might play it with a different thing or go in and out different tunes or sort of stay in a certain place. I'm coming out of the swinging and beyond tradition in jazz piano, but it's, again, that thing of staking out a wide range if you want. In other words, emotionally you play different types of music and also just that you can play really swinging music and out music and really tempered music and all these things that sort of become part of one thing. It doesn't have to be so...

Compartmentalized.

Yeah, exactly. The things flow into each other.

How did your Bedrock project come about?

First of all, when I was growing up playing, I ended up playing a lot of electric piano because a lot of the places that we were playing had no real pianos. So that led me to synthesizers in the old days. I had a Mini Moog. I had the OB-X. I was interested in that. Again, in Philly, there were musicians like Jamaaladeen Tacuma, Cornell Rochester or Calvin Weston sort of playing the freer, open funk electronic thing, and I used to play with them. Once I got to New York, I hooked up with Zach Danziger and Tim Lefebvre. We would play together in other people's groups but we also started working together as a trio. So that's how Bedrock started. I'm working on a new Bedrock CD now but I'm not sure when I'm going to finish it.

You also teamed up with Questlove and Christian McBride for the Philadelphia Experiment. That was a great record too.

I knew Chris when he was young and I met Quest years later. That was fun. We did some nice gigs.

It definitely seems you're like into quite a few things.

Well, maybe it just goes back to growing up playing lots of different types of music and enjoying it. That's where I'm at. Ready to come to Denver.

Who are you bringing for the Denver gig?

Drew Gress on bass and Clarence Penn on drums. Drew has been playing with me a long time with my trio and actually in many projects, and so has Clarence. But I first met Clarence playing in Dave Douglas's group. So, we've done a lot of gigs. We did a trio last summer in Europe and that was really nice. I love playing with him.

Follow @Westword_Music