Tucked away in the archives of the Denver Public Library is a fourteen-minute film called “The Denver Olympic Story.” An introductory note claims that it dates from 1964, but the contents indicate that it was put together much later, around 1969. It is, in any case, an artifact of a lost world — a Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce creation promoting a city that never was, in pursuit of a dream that would never come true.

The opening images, dimmed by time and digital transfer from 16mm film, feature soaring aerial shots of craggy mountain peaks looming over slopes of gleaming virgin powder. It’s snow porn worthy of Warren Miller, set to a Copland-esque score.

“The Denver Olympic story starts in a land of Olympian proportions,” the golden-throated narrator intones. “The American West. Massive. Majestic. You can feel it all around you.”

The scene shifts from the majestic Rockies to the regal Denver skyline, including glimpses of the Brown Palace and that apex of 1960s sophistication, Brooks Tower. Denver, the narrator explains, is steeped in the traditions of the West (cue close-ups of spurs, bronc riders), but facing forward, “changing and growing with the country.” The place is a transportation hub, a beehive of commerce, an arts mecca; its denizens are as fond of the ballet as they are of a hoedown. And, of course, Denverites are wild about winter sports — a point made by showing a group of dancing Native Americans, then begoggled, parka-clad white people in lift lines: “After the Indians have properly blessed the season, skiers find that the high mountains and a crisp, dry climate provide ideal conditions from November through May.”

Halfway through, the film settles into its primary mission, which is to persuade the International Olympic Committee that Denver, the United States’ anointed candidate, should be chosen to host the XII Winter Olympics in 1976. Colorado has extensive experience in staging winter sports competitions, the narrator notes, and 80 percent of the necessary facilities for Olympic events are already “constructed and ready,” with a speed-skating arena on the way. Alpine events, such as the slalom and downhill races, will be held “only 45 minutes from downtown Denver by superhighway,” at Loveland Basin and a secret gem of a place called Mount Sniktau: “These sites, virtually assured of ample snow and sunny weather, meet Olympic standards set by the International Ski Federation.”

Other events, such as the biathlon, bobsled and luge, will be staged in Denver’s mountain parks, an even shorter drive from the Olympic village, otherwise known as the University of Denver. Best of all, the ’76 games will arrive at the start of America’s bicentennial celebration and kick off an immense fine-arts festival designed to commemorate Colorado’s centennial year. Such a confluence of extravaganzas sends the narrator into raptures of incoherence: “Denver will encourage an intimacy of man’s work — of the mind and the body,” he burbles. “A festival of what man can do!”

Behind the bombast of the promo film is a hunger for recognition, the palpable ache of a cowtown yearning to move up in the world. Please like us, it says. We are a city on the brink of greatness and need only your blessing to get there: “Denver wants to share its mountains.... We hope we’ll see you in ’76!”

The pitch worked. On May 14, 1970, an exultant delegation of civic-minded business leaders and politicians returned to Denver from an IOC meeting in Amsterdam with the bid for the ’76 games firmly in hand. “This is the icing on the cake of our Colorado centennial celebration,” declared Mayor Bill McNichols.

And then, over the course of two tumultuous years, the dream unraveled. Much to the delegation’s bewilderment, many people in Colorado believed that hosting the Olympics would indeed bring the state to the brink — not of greatness, but of disaster. They complained about environmental impacts and the threat of runaway growth, a price tag that seemed to double every few months and a lack of community input in the entire process. It didn’t help that many of the claims made by the Denver Olympic Committee in order to secure the games — assertions about facilities and housing already in place, ideal alpine and Nordic sites within an easy drive of Denver, ample snow and the like — turned out to be a mix of wishful thinking, artful fudging, reckless exaggeration and pure fantasy.

Led by an obscure 34-year-old state representative named Richard Douglas Lamm, a core of young but politically savvy opponents launched a campaign to stop the project in its tracks. Dismissed as interlopers and “street people,” they managed to put the question of whether to spend public money on the Winter Games on a statewide ballot, as well as a separate initiative in Denver itself. In 1972, Denver became the only city in history to be awarded the Olympics and then spurn them. The turnabout signaled a profound upheaval in Colorado’s power structure, one that would propel Dick Lamm into the Governor’s Mansion for three terms and forever alter the state’s political chemistry.

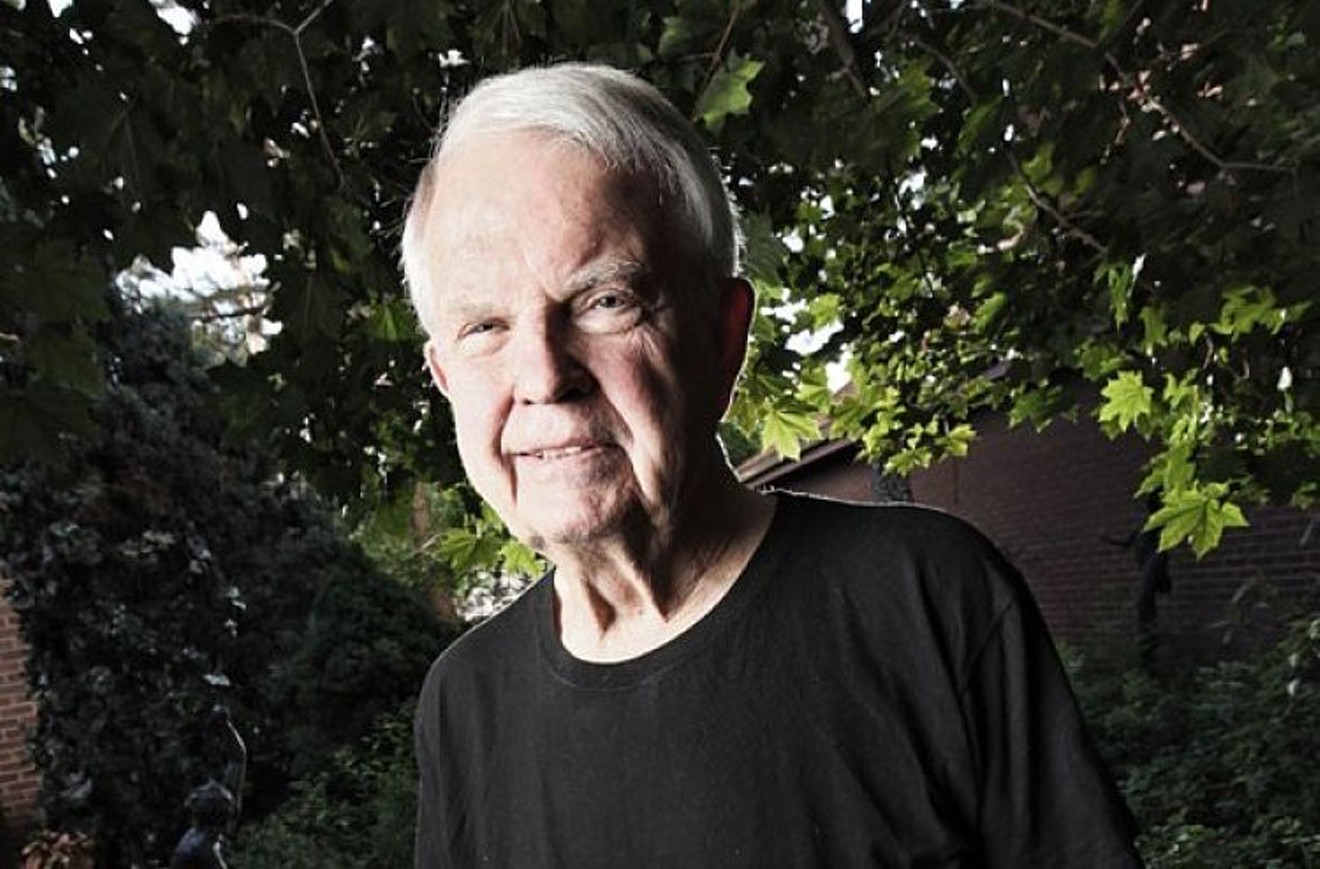

“Bismarck says that success is the child of audacity,” says Lamm, now co-director of the Institute for Public Policy Studies at the University of Denver. “We were an audacious bunch of young people. We weren’t sanctimonious, but it didn’t take us long into this battle to know we were on the right side.”

Sam Brown, one of the organizers of the campaign, says it was less about the Olympics than it was a Sanders-like effort to give a voice to the disenfranchised. “The standard story is that this was won on environmental grounds,” says Brown, who went on to become state treasurer and an appointee in the Carter administration. “To me, it had to do with the democratization of Colorado. The Denver Olympic Committee was a classic example of overreach by an entrenched and established group of powerful business interests who basically thought they could do whatever they wanted to do — without any consultation with the people. I saw it as a classic opportunity to discuss how power is distributed and mal-distributed.”“We were an audacious bunch of young people. It didn’t take us long into this battle to know we were on the right side.”

tweet this

It’s been more than forty years since Denver sent the Olympics packing. Many recent arrivals to the Mile High City have never even heard the story. But it’s a rejection worth remembering, for several reasons. The state’s current situation has overtones of that distant controversy, enough to give any armchair historian a shiver of déjà vu. Politically polarized and frustrated with the established order, the nation as a whole is in the grip of another populist revolt. Just as in the early 1970s, Colorado residents are complaining about rampant growth and Californication; about paralyzed traffic and costly mega-projects, green-lighted without the benefit of a popular vote; and about the pervasive influence of development interests and a lack of citizen engagement. And once again, business leaders are chasing a dream, one that seems to surface every few years, shimmering with the promise of delivering a big jolt of civic pride and economic opportunity and global recognition: the dream of bringing the Winter Olympics to Colorado.

It’s a hard thing to make dreams come true. It’s even harder to kill them.

The 1976 games weren’t Colorado’s first rodeo. Talk of bringing the Winter Olympics to the state dates back to the 1930s, before the local ski industry was much more than a rope tow on Wolf Creek Pass. In 1956, William Thayer Tutt, the owner of the Broadmoor, made a serious run at the 1960 games. Tutt’s idea was that the effort could be privately funded, for the most part, with the skating held in Colorado Springs — at the Broadmoor, of course — and the skiing in Aspen.

Tutt’s bid lost out to a more elaborate, publicly financed proposal to hold the games at Squaw Valley, California. Colorado boosters took away a couple of valuable pointers from the defeat. The IOC preferred to keep the events concentrated around the host city rather than spread out to far-flung locations. And a significant commitment of federal, state and local funds would be necessary to compete with well-heeled bidders from around the world.

Behind the scenes, the state’s political and business leaders began laying the groundwork for another bid. In 1963, while delivering a speech in Steamboat Springs, Governor John Love hinted that the just-opened ski resort there might play some part in the 1976 Olympics. Within a few months, Love was the honorary chairman of the Colorado Olympic Commission, a gaggle of bankers, corporate executives and other interested parties, including Tutt and Joe Coors. The group sent a delegation to Innsbruck, host of the 1964 games, to see how the Austrians did it.

In 1966, the COC formally designated Denver as its host city, leading to the creation of an eighteen-member Denver Olympic Committee. The group worked feverishly on a comprehensive proposal that would secure the backing of the United States Olympic Committee and ultimately the IOC. The bid book, as it became known, is a wildly optimistic document, stressing a determination to hold all of the events within a short distance of Denver while keeping costs down. The organizers figured the entire affair could be staged for as little as $10.8 million, perhaps $16.6 million at most. With revenues from tickets, television rights and other sources estimated at between $6.4 million and $8.9 million, the worst-case scenario seemed to be that the Olympics could run $10 million into the red — a tab to be picked up by state and federal funds.

Denver got the nod as America’s official candidate for the ’76 games a week before Christmas 1967. The courtship of the IOC then began in earnest. The local boys cranked out fancy brochures in five languages — English, French, German, Spanish, Russian — and promo films. They made the party circuit of the ’68 Summer Games in Mexico City and the Winter Games in Grenoble (where Colorado’s own champion skater, Peggy Fleming, won the only gold medal of the entire U.S. team). They bought rounds and talked up Denver at every opportunity.

Favors were expected and sometimes demanded. One grizzled IOC official suggested that a donation to the organization’s museum might help Denver’s cause. Others hinted that support by Colorado’s congressional delegation for the Pan-American Highway could win some votes from IOC members south of the border.

In all, the Denver committee spent $750,000, mostly from state funds, plus another $300,000 in donated goods and services, wooing the IOC — a pittance by today’s standards, but a hefty sum in the late 1960s. In pursuit of the Olympic dream, the group’s members climbed every mountain, followed every rainbow. They were determined to impress the pants off IOC president Avery Brundage and his phalanx of princelings, barons, tycoons and satraps.

Just how determined was something United Airlines pilot Tony Romeo discovered one crisp January day in the late 1960s. A bunch of IOC folks were in Denver, checking out the potential host city, and someone thought it would be a good idea to show them the Rockies from the air in a Boeing 727. By protocol, the visitors weren’t supposed to tour the actual sites where games might be held, but if the flight happened to cross over a few prospects, nobody was going to kick up a fuss.

Romeo, who’d flown in the Pacific during the war and had worked at United since 1951, pointed out that a 727 was required to maintain a flight altitude greater than 16,000 feet, which might limit the sightseeing a bit. He was told not to worry, that a waiver from the Federal Aviation Administration had already been obtained. As long as he kept a thousand feet above the ground at all times, everything would be fine.

“They said, ‘We want you to give them a spectacular ride,’” Romeo recalls. “And I said I could arrange that.”

The plane was packed with close to a hundred VIP passengers, a flight crew of four, and four multilingual stewardesses. Air traffic was briefly halted at Stapleton International Airport so that the flight could defy normal procedures and take off directly to the west, in order to underscore how close the Evergreen area — and the mountain parks designated for Nordic events — are to downtown Denver. Soon Romeo was sailing by Mount Sniktau and Loveland Basin, then working his way over to Vail, one of the backup sites.

The skies were clear, the day ablaze with sunshine. A fellow captain with a mellifluous voice pointed out various peaks as the plane skirted their flanks. Romeo kept below 12,000 feet. The message was inescapable: The Alps got nothing on us, pal.

As they approached Aspen from the north, Romeo dropped the big bird down to 8,000 feet, scarcely a thousand feet above the valley floor. The flyover provided his guests with a jaw-dropping view of the town and its ski mountains, with Pyramid Peak and the Maroon Bells beyond. It was less picturesque for the skiers on the hillsides, who had never seen such a large craft seemingly barreling straight toward them. Some quickly abandoned any hope of finishing their run and dove for cover.

“We were just cruising along, gently climbing to make it over the Maroon Bells,” Romeo recalls. “Everybody was looking up at the mountains, of course, but I could see these skiers tumbling down.”

Romeo circled the Elk Mountains and headed east, flying over the Royal Gorge. At some point, one of the passengers strolled into the cabin and introduced himself as the Prince of Denmark. He explained that he loved auto racing and would dearly like to see the route of the renowned Pikes Peak International Hill Climb. Romeo steered his way past Victor and Cripple Creek and came at Pikes Peak from its backside, dipping over its north shoulder so that Hamlet, or whatever his name was, could get a good look at the course. The prince turned a little green but seemed quite impressed.

The 727 drifted out to Monument Hill and back to Denver, completing one of the stranger excursions in the history of Colorado aviation. “In forty years of flying, through the war and all kinds of stuff, that was probably my favorite flight,” Romeo says.

By 1970, Denver’s relentless salesmanship had elevated the city from dark horse to a serious candidate. After Montreal was selected for the 1976 Summer Games, effectively squashing Vancouver’s hopes of hosting the Winter Games in the same country that same year, the Mile High City’s chances looked even better. It took three ballots, but the IOC finally selected Denver over Sion, Switzerland, in a 39-30 nail-biter.

The Denver team didn’t have long to savor its victory. There was a lot of work to be done to make the magic happen, and questions were already surfacing from skeptics back home about the exotic claims the group had made in its promo films and bid book. For example, there had been an explicit promise of 100,000 beds available for tourists within a short distance of the games; the actual figure was closer to 35,000. The trip from downtown to the downhill events on Mount Sniktau was supposed to be no more than 45 minutes, and that was within the realm of possibility — provided that you shut down all eastbound traffic on I-70 and ran shuttle buses on every lane of the interstate up to the mountains.

And there was a reason that few Colorado skiers had ever heard of Mount Sniktau. The place had snow on it the day Romeo took the IOC members on their tour of the Rockies, but most of the time, the 13,240-foot peak is as bare as Larry David’s head — a rocky, wind-scoured hunk of desolation more suitable for hiking than skiing. A close examination of the photos of Sniktau in the multilingual brochures revealed that heavy airbrushing had managed to fill in the bald spots with fake snow. Somehow the Denver organizers had neglected to mention to the IOC a fact that was obvious to every snowplowing newbie on Colorado’s slopes: the best, most abundant and reliable snow is found not on the Front Range, but west of the Continental Divide, on the far side of the then-under-construction Eisenhower Tunnel.

Love’s lieutenant governor, John Vanderhoof, maintained that a little bit of flim-flammery was understandable, given the kind of pressure the committee had been under to make a good presentation before the IOC. “They were pressed for time,” Johnny Van explained to one reporter, “so they lied a bit.”

The movement to stop the Olympics began as a low whine in the foothills west of Denver. Before long, it had turned into a snarling, roaring beast.

Vance Dittman had a lot to do with that transformation. A retired University of Denver law professor and resident of the Evergreen-Indian Hills area, Dittman had first learned of the plan to stage Nordic events in Denver’s mountain parks in 1967. The idea struck him as sheer lunacy. For one thing, the events weren’t actually confined to the park boundaries; the proposed cross-country course meandered through mountain residents’ back yards and would require removing several fences. The biathlon competitors would be demonstrating their marksmanship in close proximity to an elementary school and Evergreen High School.

The whole business was going to require parking for thousands of cars, which would involve removing hundreds of trees and leveling a hilltop in the area’s cherished woodlands. Worse, nobody had consulted local property owners about this grand disruption. They apparently hadn’t consulted the snow reports, either. Dittman did, and discovered that the area had a 4 percent chance of having enough natural snow in February to support the games.

Even more absurd was the prospect of spending millions to construct the infrastructure needed for the bobsled and luge competitions — including a giant, refrigerated concrete trough that would be used for ten days and then abandoned, a blight on the hillside. Lake Placid, New York, had such a track left over from the 1932 Olympics, but Squaw Valley had managed to dodge the expense by getting the events scratched from the 1960 games.

Shortly after the IOC awarded the games to Denver, Dittman and other concerned residents launched a group called Protect Our Mountain Environment. POME fired off letters to the governor, the USOC and the IOC, detailing numerous problems with the Nordic plans and demanding action. But for many months, the Denver Olympic Committee refused to consider alternate sites. “Evergreen is just going to have to eat it,” DOC public-relations director Norman Brown told a writer from Sports Illustrated.

Yet it was becoming clear that the site problems extended far beyond the objections of a few tree-huggers in Jefferson County. There was no parking at Mount Sniktau, either, no facilities of any kind, in fact, and no interest from resort operators in developing the damn place. The site had been chosen because Copper Mountain was considered too far away from Denver, but Ted Farwell, a three-time Olympian ski jumper who’d agreed to serve as the DOC’s technical director, thought Sniktau was a terrible mistake. Since the alpine and Nordic venues didn’t provide any guarantee of the “ample snow” the organizers had promised and the IOC frowned on the use of artificial snow, Farwell found himself scrambling to devise hush-hush backup plans. He eventually resigned from the DOC.

“The public-relations attitude of the DOC was: ‘Say nothing. Don’t answer. Because if you answer, you just dig yourself in deeper,’” Farwell complained in a 1973 magazine article he wrote about the debacle.

But saying nothing was hardly the way to avoid bad press. Denver Post publisher Donald Seawell was an enthusiastic supporter of the games, but his reporters couldn’t ignore the brewing controversies. And over at the Rocky Mountain News, 28-year-old managing editor Michael Howard, grandson of the co-founder of the Scripps-Howard empire, was in the process of transforming the also-ran tabloid into an investigative juggernaut. In the spring of 1971, the Rocky ran a seven-part exposé that ripped the DOC for ineptitude, misrepresentation and secrecy, pointed out the logistical problems, and examined the spiraling costs of previous Winter Games: Squaw Valley’s 1960 adventure, for example, had ended up costing fourteen times the original estimate. The paper’s coverage helped galvanize public opinion about the games and provided opponents with a wealth of damning facts and figures.

“Thank God for Michael Howard and the Rocky Mountain News,” says Sam Brown. “That series was an enormous public benefit.”

Dick Lamm thought so, too. An attorney, CPA, part-time professor, liberal Democrat and avid environmentalist, Lamm was an outlier in the Colorado legislature. In 1967, during his first term as a state representative, he’d alienated Catholic voters in his own district by championing a bill that made Colorado the first state to legalize abortion. He had few ties to the state’s largely Republican political establishment and was the most vocal of a lonely handful of lawmakers who opposed the Winter Games. In fact, Lamm was far more strident than the rest, predicting that the ’76 Olympics would be “an environmental Vietnam for Colorado.”

“I thought I was going to lose my seat over this,” Lamm recalls today. “I had some big business people talk to me, and a number of Republican legislators asked me to cool it. But then, I never really thought of myself as having a political career.”

Lamm had nothing against the Olympics in principle. While in law school in California, he’d taken a day off to check out the games at Squaw Valley and loved it. Like the rest of his colleagues, he’d voted for a resolution supporting Denver’s bid when it was still just an idea on paper. But by 1971, he’d become convinced that the whole mess was going to attract more environmental degradation and residents to a state that was already one of the fastest-growing in the country. And as a member of the legislative audit committee, he’d seen the figures coming out of the Denver Olympic Committee — and knew they didn’t add up.

“I had been trained as an accountant, and I could see they didn’t have much of a handle on either the income or the expenses,” he says. “I increasingly became skeptical. I thought they were overrating the benefits and underrating the costs. These were honest, well-meaning people who were trying to do something good for Colorado, but they were well over their heads. It’s in the DNA of every chamber of commerce: ‘Watch us grow.’”

The organizers managed to provide more fodder for the opposition with one gaffe after another. The DOC announced that television coverage of the games would be blacked out in the Denver area, in order to aid ticket sales; the only way to catch the games in town would be to pay to watch the events in local theaters. Far from stimulating sales, the decision left many grumbling about how the Olympics was a party for the elite that had nothing to do with ordinary citizens.

News also began to leak out about plans to shift the biathlon, cross-country skiing and ski-jumping to Steamboat Springs, while moving the slalom and downhill events to a new area being developed by Vail known as Beaver Creek. It was beginning to look like there would be three Olympic villages, spread over 165 miles or more. The good news was that there wasn’t going to be a fourth one; the International Bobsled and Tobogganing Federation had agreed to drop the bobsled races after the DOC suggested staging them at Lake Placid.

In the fall of 1971, Lamm began to assemble a coalition of different groups interested in placing some kind of controls on the escalating cost and scope of the games. The players included Dittman of POME, Sierra Club members and three young political activists who’d recently arrived in Colorado: Sam Brown, John Parr and Meg Lundstrom.

Brown, a veteran of anti-war organizing and the youth coordinator for Eugene McCarthy’s presidential campaign in ’68, had come to Colorado with a dog and a Jeep and a publisher’s advance to write a book about “the new populism.” Instead, he’d become involved in the 1970 congressional run by Craig Barnes, whose crusade for transparency in government had helped launch Colorado Common Cause. Barnes lost the race, but the experience had introduced Brown to Parr, another canny young organizer, and eventually to Parr’s friend Lundstrom, an aspiring journalist who, like Parr, had recently graduated from Purdue and come west. All three had worked briefly on the presidential campaign of populist Oklahoma senator Fred Harris but found themselves at loose ends after Harris abruptly closed his Denver office.

Along with environmentalist Estelle Brown — no relation to Sam — the three became core members of the ’76 opposition campaign, dubbed Citizens for Colorado’s Future. The group took out a newspaper ad titled “Olympic Fact Sheet,” which drew heavily on what the Rocky had already reported about the cost and logistical issues. The ad brought a strong response—so strong that the CCF organizers decided to send out petitions, asking for signatures from those opposed to staging the games in Colorado.

To their astonishment, they collected 25,000 signatures in three weeks. Suddenly, it seemed as if an opportunity beckoned — not to simply keep the games from spiraling out of control, but to stop them from ever coming to the Centennial State.

The way Howard Gelt remembers it, Citizens for Colorado’s Future wanted to present their petitions to the IOC, but they wanted to do it very publicly, so the documents didn’t just end up in a wastebasket somewhere. They decided to send a delegation of three to crash the IOC executive meeting at the 1972 Winter Olympics in Sapporo, Japan: Parr, Estelle Brown and Gelt, a young attorney who’d worked with Lamm.

“John was the hippie,” Gelt says. “I was the young businessman in a coat and tie. Estelle was the resident of Evergreen who had all the facts, a feisty environmentalist who believed in a cause.”

Lundstrom says a great deal of thought went into the selection — with media coverage in mind. Parr, whose mischievous dark eyes gleamed amid a mess of hair and beard, was the “implied threat,” the stereotypical protester, while Estelle played “the little old lady in tennis shoes,” and Gelt was the nice fellow with short hair, their liaison to the establishment.

Rebuffed in their efforts to arrange an appointment with the IOC, the group decided to head straight to the meeting room. Security was not nearly as tight as it would become after the terrorist attack at the Munich Summer Games a few months later, and the trio managed to dawdle near the door until IOC members started to wander out.

“As the door opened and they were going on break, Estelle walked into the room and said, ‘We’re here from Colorado, and we demand to be heard,’” Gelt recalls. “And the place went nuts.”

The executive committee’s inclination was to hustle the intruders out of there; when Gelt handed a copy of the petitions to one member, the fellow muttered something about pissing on them. But the world press was watching. The group reconvened and allowed Brown, Parr and Gelt a few minutes to air their concerns. The incident made international headlines and was big news back in Colorado.

Brundage, the 84-year-old czar of the IOC, was furious. He informed Robert Pringle, the president of the Denver Olympic Committee, that it was the unanimous opinion of the executive committee that Denver wasn’t equipped to handle the games and should be stripped of them. Pringle and other DOC members worked through the night to put together a presentation to reassure Brundage and his gang that their city was eager, willing and capable of staging the best Winter Olympics in the history of Olympicdom...a triumph of the spirit of ’76...a festival of what man can do!

The executive committee relented, and the DOC contingent returned to Colorado hugging their reprieve. But awaiting them back home was no hero’s welcome, just more tough questions about costs and siting issues. Carl DeTemple, the DOC’s general secretary, conceded that the projected cost of the games had ballooned to $35 million; three weeks later, Mayor McNichols allowed that the true cost was more in the neighborhood of $77 million. That included a $26 million federal contribution, $5 million from the state, Denver’s commitment of $12.6 million, plus a Denver Urban Renewal Authority plan to secure $31 million for press accommodations that could later be converted to low-income housing. But those figures didn’t include another $20 million that the organizers were counting on from private developers; the anticipated price tag was now high enough to justify bumper stickers denouncing the Olympics as a “$100 million snow job.”

The organizers had counted on television revenues to offset some of the expense. But right after Sapporo, the DOC got more bad news: The networks didn’t see the Winter Olympics as much of a moneymaker, given the expense of setting up broadcast facilities in remote locations. In fact, they contended that the host city should subsidize the television coverage, ponying up $10 million.

There were complaints about a proposed speed-skating arena near South High School, about having a scaled-down luge run at Genesee Park. University of Denver administrators had second thoughts about turning their campus into an Olympic village when it became clear that no one had calculated the cost of sending their students home for two weeks while their dorms were occupied by athletes from dozens of countries. Less controversial was the plan to build a $10 million sports arena next to Mile High Stadium, which could be used for hockey and figure skating and would eventually be known as McNichols Arena.

Amid all the simmering disputes, Lamm introduced a measure in the legislature proposing to pull the plug on state spending on the Olympics. “It never got anywhere and was never taken seriously,” he says.

The refusal of the legislature to turn off the spigot raised the prospect of a citizen initiative to put the matter before the voters. CCF had gathered 25,000 signatures to present to the IOC with relative ease; how hard could it be to collect the 50,000 signatures required to place the issue on a statewide ballot? The DOC responded to such talk by calling it misguided. Governor Love said that it was “too late” for a vote, that the die had already been cast; it was time for all good Coloradans to get with the program.

“It is unthinkable to me at this time and place of the history of the Olympic Games that Coloradans would stand up and say, ‘We have neither the will nor the unity,’” Love declared in a speech that spring.

Sitting at home with his wife, Tom Nussbaum watched in disbelief as Love explained to a TV reporter that there was really no time for citizens to get involved in voting on the Olympics. “I was deeply offended by that,” he recalls. “I didn’t oppose the games, but I did oppose the way they were being financed. It didn’t seem right for the ski industry to have taxpayer money to do things they could have paid for themselves. And they didn’t think the voters should have a say in how their money was spent.”

Nussbaum had been an intern for Senator Robert F. Kennedy while an undergraduate in upstate New York. He had worked on RFK’s 1968 presidential campaign while in law school at George Washington University. Recently arrived in Denver and involved in a lawsuit against the Bureau of Indian Affairs on behalf of some of its Native American employees, he still found time to visit the CCF at its offices on Delaware Street and offer his assistance. He began by seeking invitations from the Elks, Rotarians and other civic groups to talk about the Olympics cost issues. Soon he was helping to assemble an army of petition volunteers from Craig to La Junta, and from Sterling to Durango, that would number in the thousands.

“Obviously, any statewide election is going to be won between Fort Collins and Pueblo,” Nussbaum notes. “But we wanted signatures from across the state, and we got them.”

Belatedly, the pro-Olympics camp began to work on its appalling public-relations problems. The DOC opened its meetings to the public and replaced Pringle, a marketing executive at Mountain Bell seen as aloof and imperious, with W. Richard Goodwin, the president of Johns Manville. But the stumbles over costs and locations continued.

“Every time you turned around, they’d changed something else,” Lamm says. “At some point I felt sorry for them, because they caught every bad break you could get.”

“You’re running a campaign, and every morning the other side gets up and fires six rounds into their own foot,” Sam Brown says. “How good is that?”

Love formed a group of prominent businesspeople and civic leaders, the “Committee of 76,” to rally support for the games. But CCF had its own committee of 76,000 — far more than the minimum signature requirement to put the issue on the ballot. (A second petition drive put a similar question about Olympic spending on Denver’s municipal ballot as well.) Olympics supporters assembled a war chest of $175,000, roughly eight times the amount CCF had raised, to persuade voters to keep the games. The DOC even arranged for personal appearances by Jesse Owens, apparently to remind folks that the Olympics had its heroic side. It didn’t make any difference.“The public-relations attitude of the DOC was: ‘Say nothing. Because if you answer, you just dig yourself in deeper.’”

tweet this

“For every body they could bring in, we had a hundred volunteers,” Brown says. “A great deal of the energy in the campaign came from people you’d describe as concerned about the environment. But it became a lunch-bucket issue: They’re going to spend your tax dollars to support this development, which is going to benefit very few people. The growth issue motivated the workers, but the cost issue motivated the voters.”

McNichols and DeTemple continued to insist that the Olympics was a “sure thing,” even if Denver and the rest of the state voted against paying for it. This was a bluff, to be sure, since the federal funding was contingent on the state paying its share, and it was inconceivable that private interests would finance such an undertaking on their own. But posturing was about all the proponents had left in their arsenal; just weeks before the election, the DOC spewed out a pamphlet denouncing Parr and Lundstrom as “street people” and dismissing the opposition as “young political activists who have filtered into Colorado over the past two years, seeking populist issues to exploit and promote.”

The idea that young people had “filtered into Colorado” like a contagion was a pretty good illustration of the bunker mentality the DOC had adopted, Lundstrom suggests. “They were totally clueless,” she says. “They had no idea who we were or what we were doing. We were nobodies to them. The people running the state had had this good-old-boy consensus for some time. They failed to see the huge demographic shift that was happening in Colorado. I think they were just in denial about it.”

Between 1960 and 1970, Colorado’s population had grown at twice the national average; mountain resort areas, such as Pitkin and Eagle counties, had seen even heftier surges, as much as 160 percent. At least some of the growth was the result of Governor Love’s own “Sell Colorado” efforts to boost tourism and industry — but some of it could also be blamed on John Denver, the skiing boom and the state’s glorious natural resources. Many of the new arrivals were young, highly educated and politically minded, and their politics had little in common with the old order. But they were also able to connect with middle-class and blue-collar residents on “lunch bucket” issues such as the Olympics.

The youthquake had its way on November 7, 1972. Voters across the state rejected the Olympics by a sixty-forty margin. The IOC soon announced that the 1976 Winter Games would be held at Innsbruck, the 1964 host.

On election night, Lamm attended the victory party of fellow Democrat Pat Schroeder, who’d claimed the congressional seat that Craig Barnes had failed to win two years earlier. It was the beginning of a new era in state politics.

Just months before, Lamm had thought his days in public office were numbered, thanks to his support of abortion and his opposition to the Olympics. “This was not a sane thing to do,” he says, “to attack motherhood and the Olympic rings.”

But at Schroeder’s party, Lamm was hailed as a hero. Broad-shouldered local activist John Zapien grabbed him in a bear hug and lifted him above the crowd. “Ladies and gentlemen, the next governor of Colorado,” he said.

“It had never entered my mind,” Lamm says now. “I was from nowhere. I had no money, no connections. But I looked around and thought, Hmmm.”

The anti-Olympics campaign made Lamm a popular governor and transformed Colorado politically from a typical Western red state to a purple one. It did not, however, avert the frantic growth and sprawl that Lamm had inveighed against. The state’s population has more than doubled since those ancient days, from 2.4 million in 1972 to four million in 1998 to more than five million today.

“I consider one of my great political failures that I was unable to do anything about better planning standards or better development of the urban core and more open space,” Lamm says. “Somehow we couldn’t follow up on some of the positive programs that should have come out of this. Money and real estate are so powerful.”

Yet the campaign had a ripple effect that extended in many directions. “It drew in a lot of people who had never been involved in politics before,” says Lundstrom, who went on to a career as a journalist and author. “I think that had a long-term effect on the state in a lot of ways.”

Parr and Nussbaum played central roles in Lamm’s gubernatorial campaigns, utilizing the vast network of volunteers originally assembled to fight the ’76 games. Both also served as key advisors to Federico Peña in his 1983 victory over incumbent McNichols in Denver’s mayoral race, a turning point in the city’s political history. (Parr, who later became the head of the National Civic League, died in a 2007 traffic accident that also claimed the lives of his wife, Westword co-founder Sandra Widener, and their nineteen-year-old daughter, Chase.)

Denver’s embarrassing rejection of the Olympics may have also had an effect on the games themselves — or, at least on how subsequent American host cities have approached the daunting task of staging them. Lamm praises Peter Ueberroth, organizer of the 1984 games in Los Angeles, for “staring down the IOC” and arranging the first privately funded Olympics — and generating a quarter-billion-dollar surplus. The 1996 games in Atlanta and the 2002 games in Salt Lake City also relied heavily on private sponsorship and claimed to operate at a profit, in addition to helping finance needed infrastructure improvements.

Critics of the games, though, say such ventures tend to be the exception. It took Montreal thirty years to pay off debts from the ruinous 1976 Summer Games, they point out, and the IOC’s taste for shiny new facilities, coupled with host countries’ desire to turn the ceremonies into a showcase of national aspirations, has since made the cost of staging the games insanely expensive. The price tag for the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics, an unprecedented wallow in excess, was reportedly upwind of $50 billion. While the Winter Games scheduled for South Korea (2018) and China (2022) probably won’t top that, just the cost of preparing a competitive bid for the games can now run $25 million or more.

“You’re running a campaign, and every morning the other side gets up and fires six rounds into their own foot. How good is that?”

tweet this

But the rising costs haven’t discouraged local boosters’ pursuit of the dream. In the late 1980s, reeling from a slump in the energy industry, the Peña administration made another play for a future Winter Olympics, proposing to stage ice events at McNichols Arena, skiing at Steamboat or Beaver Creek, and an Olympic Village on the University of Colorado’s Boulder campus; the USOC decided to back Salt Lake City’s 2002 bid instead. In 2003 there was talk of Denver going after the 2014 games; in 2010 another push surfaced for the 2022 games, with local backers estimating they could pull it off for a mere $1.5 billion.

Both efforts fizzled, largely because the USOC is focused on obtaining the Summer Games in Los Angeles in 2024. “There’s nothing active right now, as far as the bid process goes,” says Matthew Payne, the executive director of Denver Sports, which works with Visit Denver on the city’s major sports-marketing efforts. “We try to keep our relationship with the USOC strong and the line of communications open.”

Payne says that his team continues to work on bringing other national sports championships to Denver, such as volleyball or fencing, as a way to demonstrate to the USOC that the city is capable of staging Olympic-level events. The master plan for the billion-dollar renovation of the National Western Center designates a new 10,000-seat arena on the stock show grounds as suitable for hockey in a future Olympics bid, as well as a new exhibition hall that could accommodate an “Olympic long track speed skating oval.”

Lamm says he isn’t categorically opposed to another attempt to bring the Winter Games to Colorado. "They might make it work, but these are very hard things to fund and pull off,” he says. “I don’t think there’s a snowball’s chance in hell that the IOC will come back here, especially when we still have the initiative-and-referendum process, and somebody could come back and do what we did.”

William Hybl thinks Denver’s chances might be much better than that. President of the USOC for four Olympics and a former member of the International Olympic Committee, Hybl points out that senior IOC officials have visited the state several times in recent years to attend various sporting and administrative events. “I didn’t see any resentment that was substantial,” he says. “I saw a number of positive impressions that IOC members had about Colorado. Denver has had an exploratory committee at many of the international events, and I think they’ve been well received.”

Now the chairman and CEO of the El Pomar Foundation, Hybl was elected to Colorado’s state legislature in 1972, amid the campaign to kill the ’76 games. He was a supporter of the Olympics and saw their defeat as a referendum on growth rather than a rejection of the games themselves. “I think it would have been good for the state and good for the nation,” he says. “The economic impact would have been positive and probably substantial. The legacy, particularly in the snow sports, is something that would have endured.”

Hybl believes that Denver, by partnering with Vail or Winter Park for the snow events, could be a viable candidate in the future. “The significant hurdle is to be designated by the USOC as the candidate city,” he observes. “I have to believe that if Los Angeles is successful or not, you’re going to see the USOC look carefully at a winter bid at some point. There would have to be some capital improvements in Colorado, but many of the venues are ready. They just have to be set up for Olympic sports.”

And so the dream endures.

“You could do an Olympics that would make a lot of sense,” says Sam Brown, “if you had games where actual athletes were the focus, in venues that already exist. There’s stuff around, if you did it thoughtfully and made it pay for itself. But I think people are right to be skeptical.”

Watch "The Denver Olympic Story":