On a typical weekday, Roy Dockery can be found inside a wide, one-story brick building in a northeast Denver industrial park. The corporate setup appears to be modeled after an advertisement in an office-supply catalogue, with high-walled cubicles forming a maze across the center floor and a few closed-door offices dotting the perimeter. Dockery occupies one of them. As vice-president of field operations for Swisslog Health — an international corporation with employees in twenty countries — Dockery is in charge of a team of 108 employees, overseeing the maintenance and installation of automated services such as pneumatic delivery systems and robot-automated inventory programs in medical facilities.

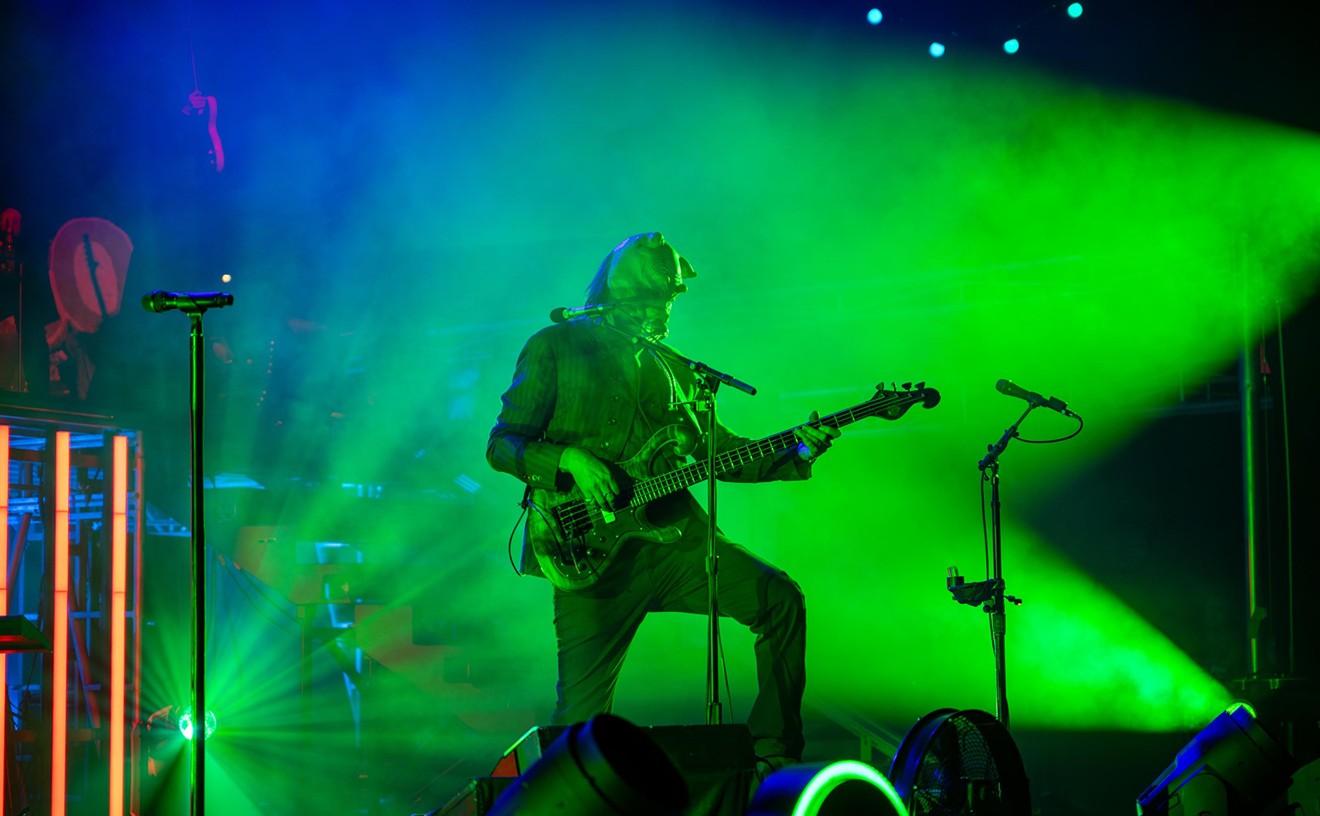

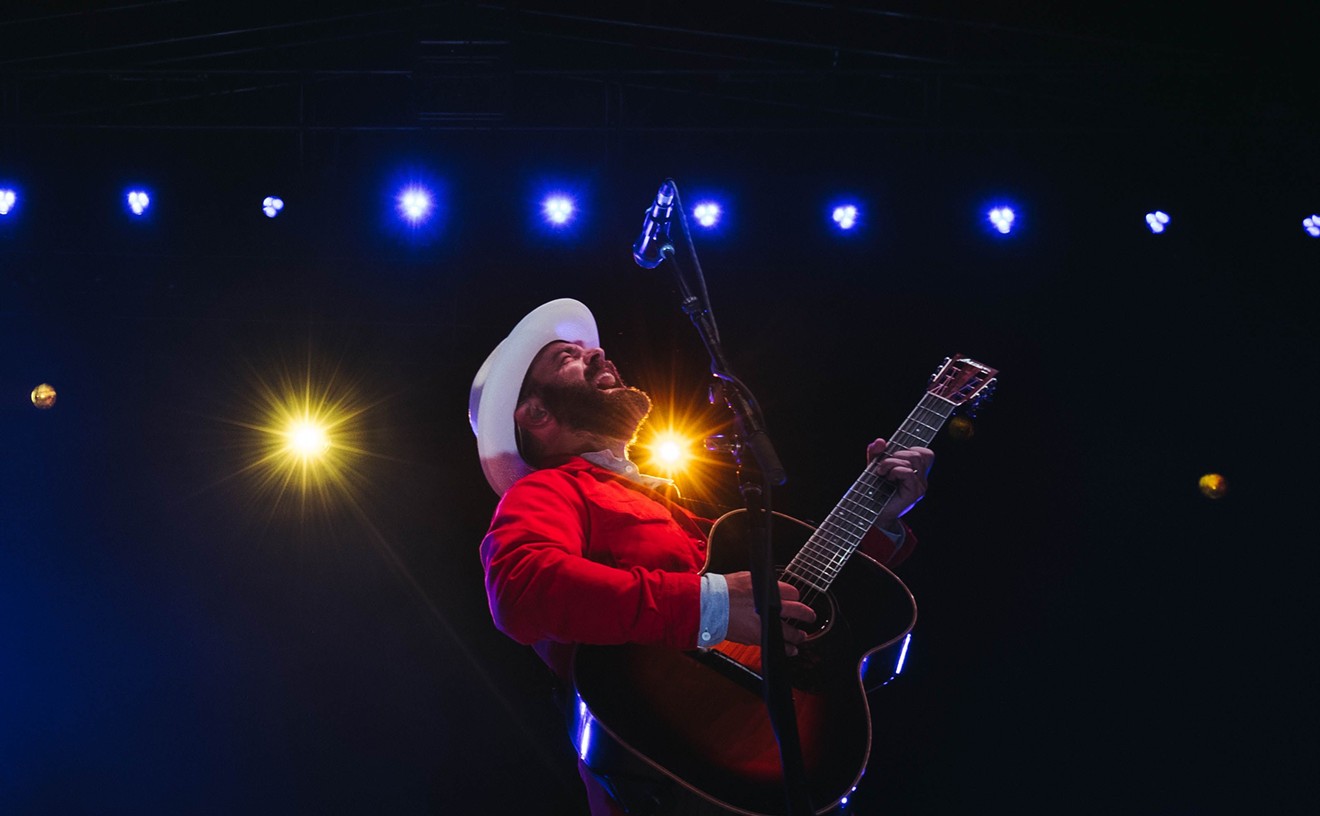

Look for Dockery on a weekend, though, and you’re likely to find the 33-year-old business executive in a far different setting: performing rap music under his stage name, Roy-al.

Roy-al is Dockery’s hip-hop alter ego, and it’s not on display in the workplace — at least not overtly. There are no obvious photos of Dockery’s rap performances among the college degrees, artwork and family portraits he has hanging on his office walls. Nor would one guess that Dockery just released a Christian-rap album called Worthy last month and helps produce other Christian hip-hop artists in Aurora. In fact, he’s been performing rap music since he was nineteen years old.

But hip-hop is more than just a hobby: Dockery claims that he never would have gotten where he is in business without it. He believes that learning to rap, rather than any specific degree or GPA, was the X factor that allowed him to rise through the corporate ranks. By studying and performing hip-hop, he says, he gained confidence and developed critical skills needed to succeed in a corporate setting, especially in the areas of improvisation, vocabulary and leadership.

And not only does Dockery believe that hip-hop helped him become a leader, but he’s convinced that others can gain business skills from the music just as he has.

A number of successful hip-hop artists have built vast media empires around their music: Just look at Dr. Dre’s $3 billion Beats deal with Apple, or Jay Z’s Rolodex of companies associated with his brand. Others, like Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs and Russell Simmons, are continually tapped by business magazines such as Fast Company and Businessweek for their entrepreneurial insight.

But Dockery differs in that he is among a small but growing number of hip-hop performers who have professional careers completely unrelated to their music. Matt Kawadler, a Chicago-based financial consultant who performs under the stage name Klaww, is also in that group. Both Dockery and Kawadler say that they’ve benefited in corporate settings thanks to the skills they developed rapping in front of crowds.

Adam Bradley, co-author of Common’s memoir and a professor of English at the University of Colorado Boulder who frequently studies hip-hop, believes that the hip-hop-inspired businessman is partly a product of the times. “Now that hip-hop is essentially in its middle age, we live in a time in which there are hip-hop everybodys — hip-hop architects, hip-hop doctors, hip-hop businessmen.... They are all children of [the music], bringing that renegade spirit that animated hip-hop at its birth into all sorts of endeavors,” Bradley says.

Bradley also believes that Dockery’s claim of learning business skills through rapping has merit. “There are a handful of skills that a rapper has to cultivate that would have immediate applicability in a business context,” Bradley says. “If you can face down a street-corner cypher or basement battle session, then you can go into any boardroom in America and keep your shit together.”

That, at least, seems to be the case for Dockery, who says that he can trace the course of his hip-hop education back to one critical moment when he was growing up.

At nineteen, Dockery was in a college dorm room in Greensboro, North Carolina, when he heard two words that terrified him to his core:

“Rap it!”

“But...I...I don’t rap — I don’t do that. I’m a writer,” Dockery stammered.

He stared blankly at the poem he held in his hands. At the time, Dockery says, he was painfully introverted, a keen observer who didn’t like to talk much and planned to become a high-school computer-science teacher. While he enjoyed listening to rap music, the only times he ever spit rhymes himself was in his car, playing music and rapping along to it. He even kept his poetry to himself, save for one or two recitals he’d done for family members.

But college friend Quinton Littlejohn wouldn’t let up, and continued to play a beat on his keyboard. “No, you wrote it, so rap it!” he commanded.

In a panic, Dockery began rapping in the only style he could think of, that of his favorite artist, Tupac.

The result was surprising, and Littlejohn was impressed.

So impressed, it turned out, that he entered himself and Dockery into North Carolina A&T State’s homecoming talent show, whose audiences were notorious for booing performers they didn’t like. On the night of the show, it was panic all over again for Dockery, including four or five seconds when his microphone didn’t work on stage. But once again, he rose to the challenge, and the performance ended up winning second place overall in the competition.

“It was not something I wanted to do,” Dockery recalls. “If it had not gone well, I might not have kept doing it. But after that I no longer had a fear of public speaking. Initially it was just performing music, but then I just became comfortable expressing myself, period.”

Not that Dockery sought to be outspoken, but after some students and faculty members heard him rapping in front of crowds, they started approaching him to ask his opinions on everything from class readings to current events.

“Those people coming to me was like an external trigger, putting me in a position where I started leading,” Dockery says.

Hip-hop also influenced Dockery intellectually, after he discovered a list of Tupac’s favorite philosophical texts in Michael Eric Dyson’s biography of the late rapper, Holler If You Hear Me. Dockery had never read many books outside of school assignments, but he found Tupac’s reading list engrossing. He immersed himself in famous works like Machiavelli’s The Prince, Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy, and Sun Tzu’s The Art of War.

Coupled with the confidence he’d gained through rapping and public speaking, the books expanded Dockery’s perspective. He decided he no longer wanted to become a high-school computer-science teacher.

Instead, he spent six years in the Navy, some of it working as an instructor at a nuclear power plant. Then in 2010, he moved to his current company, Swisslog, advancing up the ranks from a field technician to his current position as vice-president of field operations in the span of five years.

He never forgot his roots during that time, however: Dockery spent his weekends writing and performing rap music.

Matt Kawadler, who works for a top-tier strategy consulting firm (he’s not allowed to say which), also believes that his professional career has been aided by performing hip-hop.

The 31-year-old began freestyling when he was in high school and kept working at it while pursuing an MBA at Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management. In early 2013, he even opened for Method Man in Chicago.

“I think there are definitely parallels,” Kawadler says of his rap persona, Klaww, and his consulting gig. “[Hip-hop] is all about, ‘What can I say, and how can I build it up quickly in a way that everyone else in the room will instantly understand?’”

He compares this to pitching ideas in business: “If you get in an elevator with someone and you’re there for thirty seconds, you’d better know exactly what you’re going to say to get that person’s attention. That’s exactly what hip-hop is with freestyling: Your first thirty seconds had better be good.”

Professor Bradley adds that hip-hop is a meritocracy, forcing rappers to earn the respect of their audiences through wit and improvisation, both of which are powerful assets in business. “There’s a risk that one exposes oneself to as an MC in a public setting, as in a business setting,” he points out. “It’s a high-wire act in language, and often the need to improvise is key — to have a set plan, but also know when to deviate from it. And sometimes to fail, but to keep going at it.”

Dockery says that he often tailors business presentations in the same way that he adapts rap performances for specific crowds.

Despite all the lessons that hip-hop has taught him, however, the fact that Dockery is a rapper is not universally known among the employees at Swisslog. Dockery thinks that the phenomenon of the rapping businessman is still new enough that there is sometimes a disconnect between the two cultures. In part, that has to do with lingering negative perceptions of the musical style, making it hit-or-miss as to whether a co-worker will react positively to the idea that a company executive likes to throw down verses in his spare time. There’s also the fact that Dockery performs Christian rap, adding religion — another taboo topic in many workplaces — into the mix. “I think some people just don’t know how to respond to it,” he says.

As a result, he doesn’t go out of his way to hype Roy-al when he’s in the Swisslog office. “At work, it’s work,” he says.

Then again, the rap side of Dockery’s life is not exactly difficult to uncover. His performances are well documented online, especially on his social-media accounts. That’s usually how close co-workers — like his human-resources manager, who saw a Facebook post he made one weekend in July — find out.

“Um, Mr. Dockery, let’s talk,” she said upon encountering him in the office on Monday morning. But the stern tone turned out to be a joke; instead, she complimented him and said that she thought his passion for music gave him more depth.

“The payroll department here are also fans,” notes Dockery with a chuckle.

But while he used to freestyle for co-workers back when he was a field technician, Dockery says that he no longer performs at work. “Now that I’m a vice-president, no one is going to ask me [to freestyle], because they work for me. They’re not going to tell the boss what to do,” he explains.

Kawadler says that that’s not the case at his office, where he’s been asked to freestyle many times. “People thought it was cool,” he says. “Maybe things would have been different with hip-hop fifteen years ago, but they respect that I have a passion for something.”

Dockery and Kawadler both say that their business pursuits have started to return dividends for their music.

Kawadler runs his own hip-hop label, Klaww Entertainment, which he launched while he was in business school, and he’s doing more producing than performing these days, he says. “The skills I learned in business helped my label become successful — and vice versa, in that the lessons I learned in hip-hop have made it easier for me to pitch the ideas I have. Both have complemented each other very nicely.”

For his part, Dockery has a promotion company called On Faith Entertainment, which works with Christian hip-hop artists. In Colorado, he’s produced shows with the Hip Hop Church of Denver, and plans to do more shows in Fort Collins and Colorado Springs in 2016. His business partner is none other than Quinton Littlejohn, the friend who first challenged him to rap when he was in college.

There’s been another unexpected outcome of pursuing a professional career while rapping on the side: It’s helped spread the art form to new fans. Over the years, Dockery says, a number of co-workers have become hip-hop fans because they knew him before listening to the music. “It puts a face to the music and moves beyond all the gimmicks,” Dockery says. “When they know me first as a person, they associate the music with me. Then they can say, ‘Oh, well, I guess regular people rap, too.’”

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]