Lisa Kinzel

Audio By Carbonatix

The Colorado School of Mines was founded by men looking to make their fortune digging for gold. So it’s fitting that a unique discovery was made while clearing out storage space in the dirt basement of the oldest building on campus, Engineering Hall.

“They were cleaning out the space and one of our facilities folks – Mike Ray is his name – was looking up on one of the shelves, and tucked away in the top of this shelf, in the back corner of the bowels of this building, was this rolled up piece of canvas,” says Lisa Kinzel, director of research development at Mines. “And so he brought it up to me, and he unrolled it on my conference table, and we just stared at it.”

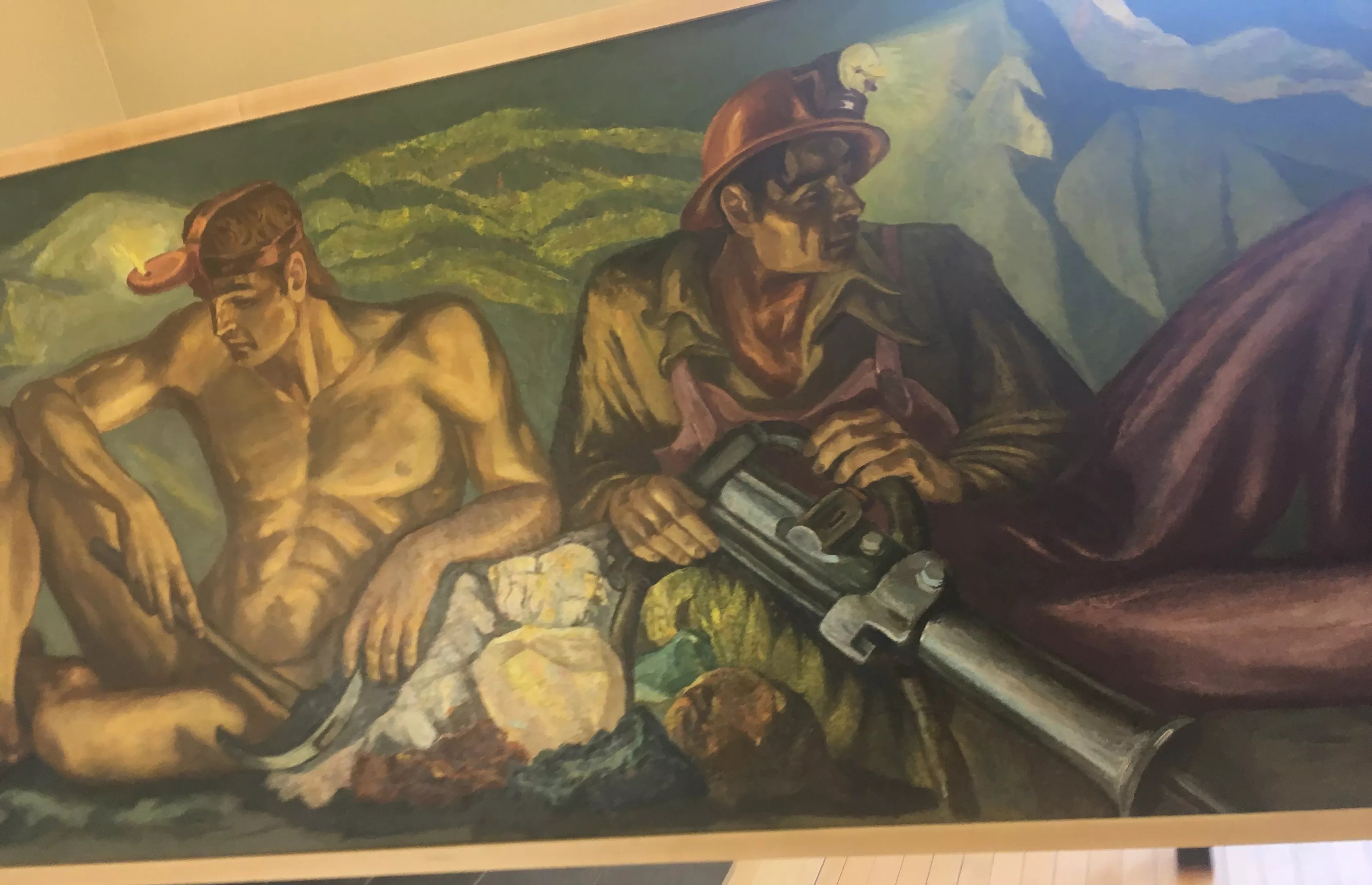

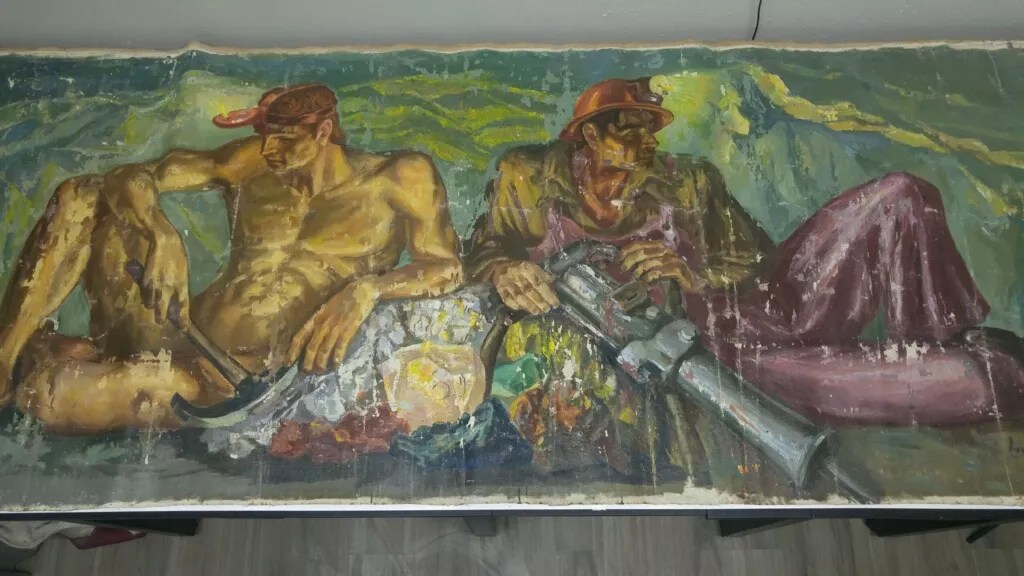

Close-up of paint damage on an Irwin Hoffman painting rediscovered at the Colorado School of Mines.

Lisa Kinzel

It was a painting – a very old painting of two miners. Reclining in opposite directions, one figure was nude and the other wore a hardhat. It didn’t take long for Kinzel to recognize the classical style of an artist whose works have hung in the school since 1940, when Barney Whatley and his wife donated to the school The History of Mining, a series originally painted by Irwin Hoffman for the San Francisco World’s Fair in 1938. Until the seventh painting was unfolded in 2017, no one seemed to know it existed.

The six known seven-foot panels displayed in the Geology Museum begin with the discovery of flint and move through the major ages of metallurgy, including the Iron Age and the Bronze Age.

The sixth panel, which has long been seen as an ode to the world made possible by mining, includes both pros and cons of technological development. Among an ocean liner, a train and a radio, Hoffman also painted “an anti-aircraft battery manned by a crew in gas masks,” wrote Theresa Cederholm in an account of the artist’s life she wrote for the Boston Public Library. “The irony of this tribute to technology implies that civilization has reached the crossroads. Will the process of development and construction outstrip the forces of destruction?”

Because the paint on the newly discovered artwork was cracked and flaking, Kinzel called in Cindy Lawrence, the art conservationist who had restored the other Hoffmans in 2014.

An Irwin Hoffman painting was discovered at the Colorado School of Mines, but it was in rough shape.

Lisa Kinzel

“This one was in particularly bad shape,” says Lawrence who restored the new painting. “We almost never have what one would consider lost causes…but this was getting there.”

Lawrence considered “trying to preserve the piece as the artist intended” a fascinating process.

Trevor Byrne of Dry Creek Gold Leaf, the framer who designed a simple maple border for the painting, recalls, “We don’t often come across art that was found that no one really knew about.”

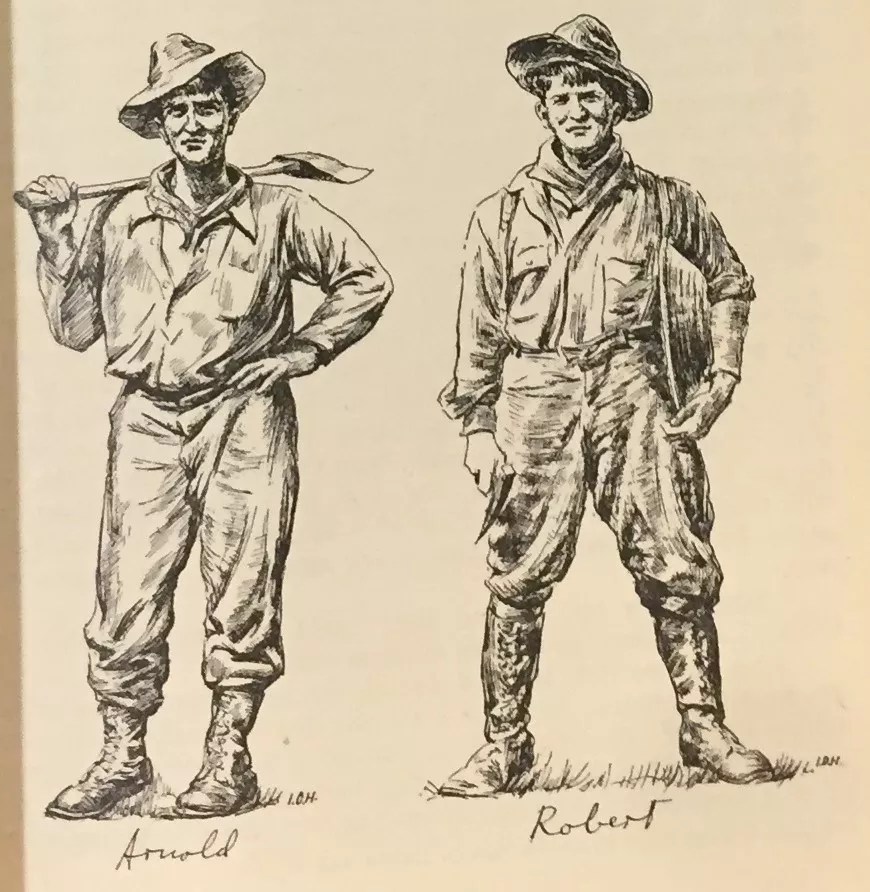

Irwin Hoffman’s sketch of his brothers Arnold and Robert, originally published in the book Free Gold.

Amanda Pampuro

Born in 1901 on Chelsea Street in East Boston, Irwin Hoffman was the youngest of four sons of Russian immigrants. Older brothers Arnold and Robert studied mining geology at Harvard and had successful careers. Irwin’s parents recognized his talent for drawing from a young age and sent him to the Boston School of the Museum of Fine Arts. Considered a portraiture prodigy, Hoffman sat in on classes at the school until he was actually old enough to enroll and then received a full scholarship. After graduation, he received the school’s Paige Traveling Scholarship and continued his studies exploring the European countryside and northern Africa.

In 1981, Hoffman recounted some of his experiences for the Boston Public Library. The text, Irwin Hoffman: An Artist’s Life, is one of few surviving resources describing his life.

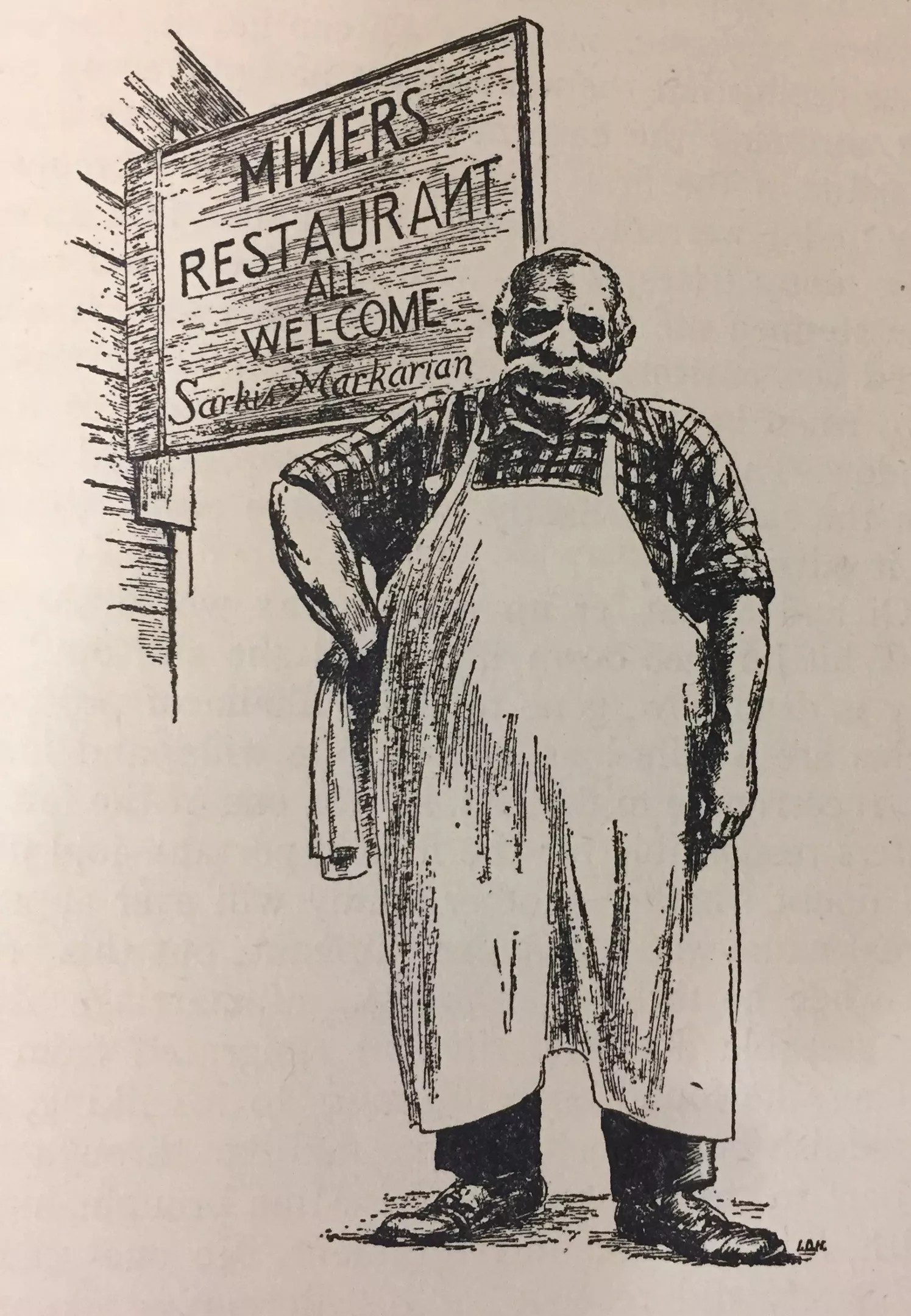

Illustration of Johnny Dillon, by Irwin Hoffman for Free Gold, a book on Canadian mining written by his brother Arnold.

Amanda Pampuro

Describing his studies, Hoffman told the Boston Public Library that Paris “was full of young artists and Russian refugees…everyone was acting crazy and having a swell time. … Days were devoted to copying at the Louvre and working in various ateliers…but even more time was devoted to raising a beard, a moustache, and a lot of hell.”

Illustration by Irwin Hoffman for Free Gold, a book on Canadian mining written by his brother Arnold.

Amanda Pampuro

By the 1940s, Hoffman had made a name for himself as an artist and journalist, documenting the lives and faces of America’s working class. His work is marked by a sense of classic rhythm, poignancy and simplicity. He painted mining in Mexico and Appalachia, and when one of his brothers wrote a history of Canadian mining titled Free Gold, Irwin provided the illustrations.

Until his death in 1989, Hoffman worked tirelessly out of a studio in New York. Lawrence postulates that the seventh Hoffman painting may have been hung over the door at the World’s Fair exhibition hall, like a title, to tell people what lay ahead. Questions remain about how the painting became separated from the rest, or how long it was stored in Engineering Hall.

Although those questions may never be answered, Hoffman did leave behind remarks about his process and the work that went into it.

“I went down every morning for two months and sketched in preparation for the murals I did for the San Francisco World’s Fair in 1938,” Hoffman said. “Words cannot explain the mysterious and unreal quality of the world underground. It is a mixture of the dramatic and the ominous; it is felt rather than visual.”