Courtesy of Bridget Dandaraw-Seritt

Audio By Carbonatix

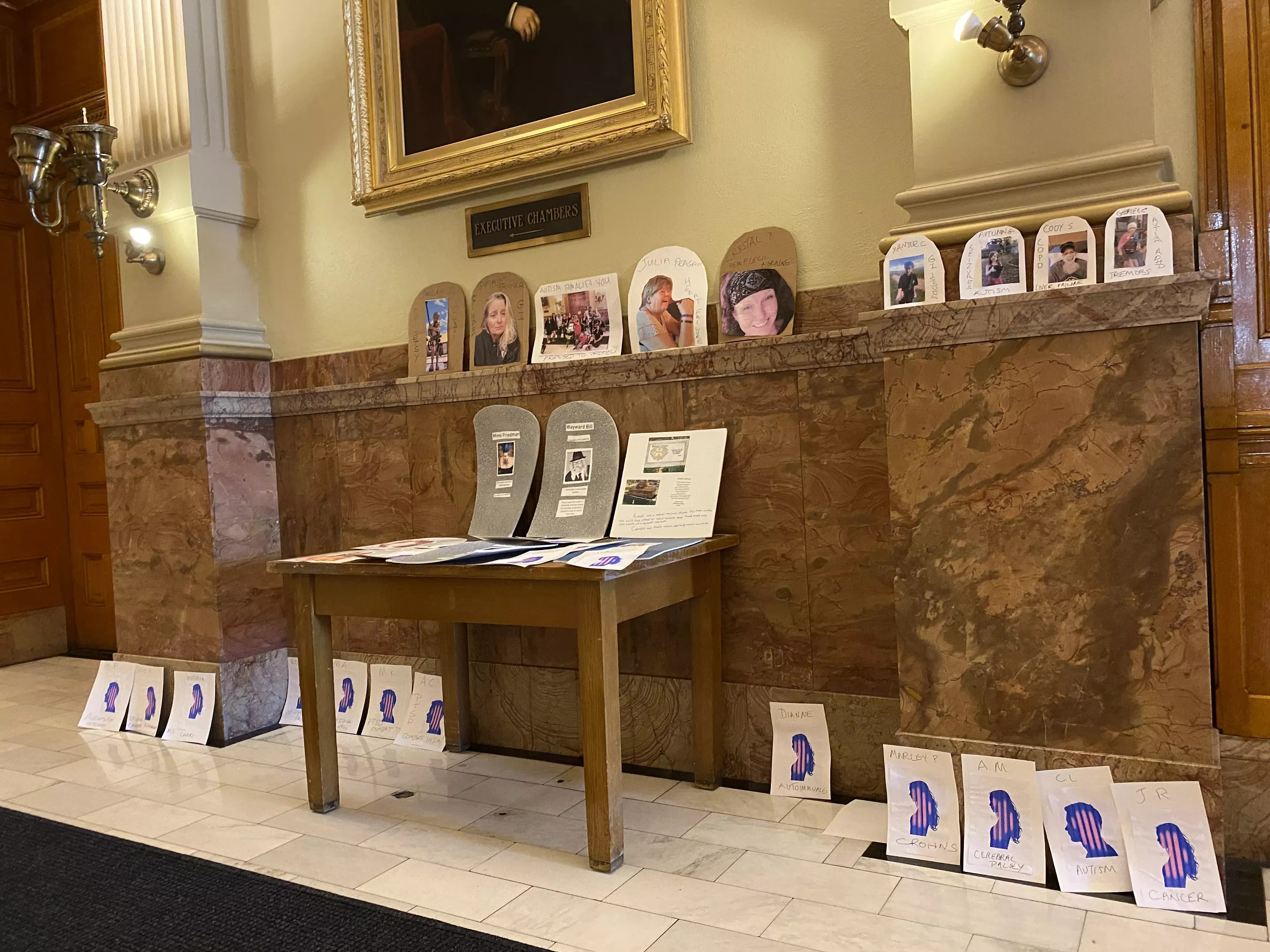

Medical marijuana patients staged a symbolic funeral in front of Governor Jared Polis’s office at the State Capitol on August 16, mourning what they view as the death of Colorado’s medical marijuana program.

Cards and cardboard gravestones with the faces and names of medical marijuana patients were placed on the ledges and a table outside of Polis’s office. The material represented what could be the result if House Bill 1317‘s changes to Colorado’s medical marijuana program are implemented, organizers said.

When they introduced the bill, lawmakers explained that they wanted to curb medical marijuana access for eighteen- to twenty-year-old patients; some suggested that group was responsible for a recent spike in youth use of potent marijuana concentrate, which could exacerbate mental health disorders.

But medical marijuana advocates believe that many more patients outside of this small age group will be bearing the brunt of the law.

The medical marijuana community had called on Polis to veto HB 1317 immediately after the bill’s passage, criticizing the changes the measure would bring to medical marijuana evaluations, recommendations and sales. The new law adds several layers of protocol for patients and physicians, including a required THC dosage amount and suggested consumption method, as well as a review of a patient’s mental health history before a recommendation is made.

Despite the pleas of MMJ advocates, Polis signed the bill into law in June. He’s now being sued by a nineteen-year-old patient for doing so, and complaints continue.

“We treat many different conditions with cannabis where pharmaceuticals haven’t been effective, and the limitations in 1317 are going to move cannabis out of the hands of patients for a number of reasons,” patient Bridget Dandaraw-Seritt said at the protest.

Patients worry that requiring doctors to include dosage and consumption rules with a medical marijuana recommendation effectively renders it a prescription, and doctors with prescription power must register with the Drug Enforcement Administration, which doesn’t allow prescribing Schedule I drugs. Doctors recommending medical marijuana will be limited to working within the respective scopes of their practices or would need recommendations to be approved by an additional physician, which could also reduce patient access, critics say.

Additionally, under the new law, all marijuana concentrate products, both medical and recreational, will fall under new packaging or labeling rules created by the state Marijuana Enforcement Division in 2023, which will likely raise the cost of marijuana concentrate. With medical marijuana still federally illegal, Dandaraw-Seritt thinks that HB 1317 puts patients in an untenable position.

“None of this is covered by insurance. It’s all out of pocket. Many patients are already spending hundreds of dollars just to stay alive or keep their loved ones alive,” she said. “It’s going to raise the costs of those grams to where I’m not able to afford it, and I’m going to have to go back to the underground market. We have people who rely on specific dosing, and the underground market can’t get its stuff tested.”

Under the law, there will also be a statewide tracking system for patient purchases, which are capped at 2 ounces of flower or 8 grams of concentrate, and new patients between the ages of eighteen and twenty will face additional obstacles to obtaining a medical marijuana card, as well as a 2-gram limit on concentrate purchases per day.

Dandaraw-Seritt, who suffers from autoimmune disorders and a genetic collagen processing disorder, says that she uses around 3 grams of concentrate per day and can’t drive, and she doesn’t see why someone in a similar position would need to surmount such obstacles to obtain medication.

Many of the new policies required by HB 1317 are still being fleshed out at MED rulemaking meetings, including concentrate packaging requirements and qualifications that would allow homebound patients to purchase more than the standard daily limit.

But some people aren’t waiting for this work to be done and have already moved out of the state, according to Dandaraw-Seritt. “We’ve already had four patients I know of who have moved. They’d rather live in a trailer in Oklahoma than get their medication from the underground market,” she said. “Oklahoma is definitely not one of the places I would’ve thought has better medical marijuana laws than we do, but at this point almost anywhere does.”

While Dandaraw-Seritt and her fellow protesters didn’t get a chance to meet with Polis, a member of his staff eventually collected the cards and cardboard gravestones, and said she would share them with the governor.