Audio By Carbonatix

As a disabled mother of two, including a thirteen-year-old autistic son, Autumn Brooks is used to going the distance for effective medication.

As long as it’s legal.

Brooks spent the better part of three years trying to make sure that her son Raven had legal access to medical marijuana at school. She started her campaign by educating herself on how cannabis affects autistic children, then advocated for autism to be added to Colorado’s list of acceptable conditions for medical marijuana use. After the Colorado Legislature did so in 2019, Brooks spent the next year securing a medical marijuana card for Raven and lobbying his school district to allow medical marijuana to be administered at the school.

With the help of other parents in the medical marijuana community, Brooks was eventually successful.

“On a weekly basis, we were evacuating his classroom because he was having a meltdown,” Brooks says of the days before Raven started taking a high-THC, low-CBD oil medication. “Then he was thriving, and it wasn’t just my son benefiting. His peers benefited, too.”

As Raven’s aggressive outbursts and self-injuring largely ended, his verbal communication increased. Even so, when it comes time to renew Raven’s medical marijuana card, Brooks plans to let it lapse, just as she recently did with her own, despite the pain relief that cannabis provides for her autoimmune disorders.

“If we go back to rules that work for him, then yes, we’d reapply,” Brooks says.

The new rules that pushed Brooks away from Colorado’s Medical Marijuana Registry resulted from the legislature’s 2021 passage of House Bill 1317, an expansive law that created new restrictions and mandates for medical marijuana and commercial marijuana concentrate. As a result of those rules and regulations, Colorado is now losing medical marijuana patients and doctors, many of whom believe they’re no longer welcome in a state that was once a pioneer in the use of medical marijuana.

Under the new law, presented by proponents as a guardrail to protect kids from potent legal marijuana products, physicians are required to include a THC dosage amount and form of THC consumption with medical marijuana recommendations. Physicians recommending medical marijuana can no longer diagnose patients on their own, either; an outside diagnosis from another doctor is now required.

The law also limits medical marijuana concentrate purchases, creates a new statewide tracking system for medical marijuana dispensary transactions, and adds more application restrictions for patients eighteen to twenty years of age, including mental health reviews. The new concentrate purchasing limit, cut from 40 grams to 8, would force Brooks and others who rely on highly concentrated cannabis oil to visit the dispensary more often, while stricter instructions related to dosage and consumption methods would restrict what they’re allowed to buy there.

“The reality is that the doctors don’t tell us how and what to use. We have to learn what works for us on our own. If I say a terminal or cancer patient finds they need high-potency oil, which is often the case, they’re not going to be able to get the amount they need. Cannabis is not a one-size-fits-all,” Brooks argues.

“Patients weren’t listened to the entire time as this was written,” she adds. “This whole process, we’ve been shut down.”

Autumn Brooks (middle row, fourth from left) and Michelle Walker (second from right) pose with their sons for a group photo at the State Capitol in 2019.

Melanie Rose Rodgers

It wasn’t always this way. For more than a decade, Colorado was viewed as an asylum state for medical marijuana patients and their families. The state’s voters had legalized medical marijuana in 2000 by passing Amendment 20, granting patients or their designated caregivers the right to grow their own cannabis. In 2001, Congress passed legislation barring the United States Department of Justice from using federal funds to interfere with state-legal medical marijuana programs, giving more breathing room to patients and their caregivers.

The caregiver model and looser federal enforcement enabled designated cannabis growers to cultivate plants for registered patients who were unable to grow their own. This created a home-growing landscape across Colorado that planted the seeds for stores that would serve as caretakers for multiple patients.

In 2009, U.S. Deputy Attorney General David Ogden issued a legal memorandum for U.S. attorneys regarding how to approach states with legal cannabis, suggesting that they take a hands-off approach toward complying businesses. Shortly after the release of the Ogden Memo, medical marijuana dispensaries began popping up all over metro Denver, partnering with patients who registered the dispensaries as their registered caregivers.

Even as advocates for recreational marijuana sales began pushing Amendment 64, Colorado’s reputation as a medical marijuana-friendly place grew. And then in 2013, Sanjay Gupta’s WEED documentary on CNN featured child patient Charlotte Figi, who used cannabidiol (CBD), a compound of cannabis, to treat a rare form of epilepsy.

The documentary and the story of Figi, who passed away in 2020, elevated the reputation of Colorado’s medical marijuana program, putting it on par with those of a few states that had been early adopters, such as California and Oregon.

Having heard stories about medical marijuana refugees who’d moved here, Michelle Walker came to Colorado in 2017 looking for treatment for her son, Vincent Zuniga, who suffers from severe autism. Like Brooks, Walker pushed the legislature to add autism to the list of accepted medical marijuana conditions, and she’s remained an active member of Colorado’s cannabis community ever since.

After putting her son on a high-CBD, low-THC medication, Walker says, she saw dramatic improvements in his emotional and cognitive abilities. But after HB 1317 passed, she briefly considered leaving the state, worried she’d be unable to find two doctors to agree to renew Vincent’s medical marijuana card.

“We’ve talked about all of our options, even going to another state again, which is ludicrous.”

“We’ve talked about all of our options, even going to another state again, which is ludicrous. We won’t be moving, but that being said, if we can’t get a medical card for our son, I’ll continue to medicate him,” Walker says. “I have two choices, and that’s either break the law or plan my son’s funeral. I’m not going to let special-interest politics dictate how to medically care for my son.”

While Walker admits she’s privileged to be able to afford two doctor diagnoses for her son, she says that the process puts extra stress on an already-fragile community, both medically and emotionally.

“We’re still in the throes of a pandemic, and immunocompromised children can’t be running around during flu and cold season. We were already at risk,” she says. “Autistic children are a handful after a bad experience. It will be hell if we have to go to an office again after Vincent’s had a bad experience. These are strenuous visits for families like mine.”

Even if you can afford the doctor visits, Brooks notes another problem: a lack of doctors willing to write recommendations at all.

Charlotte Figi became the unofficial face of Colorado’s medical marijuana program.

Courtesy of Paige Figi’s Facebook page

Dr. Laura Lasater spent over a decade at Denver Health before becoming a medical marijuana physician at Healthy Choices Unlimited clinics. Proud of her work in getting patients off opioid medication, often with the help of medical marijuana, Lasater reluctantly resigned on January 1, when HB 1317 was implemented.

Lasater says that she and other doctors worry they could lose their license to practice altogether if they follow the new law to the letter.

Before January 1, medical marijuana was recommended by Colorado doctors, not prescribed. According to Lasater, noting specific dosage and ingestion methods as required by HB 1317 would turn those recommendations into prescriptions, and doctors with prescription power must register with the Drug Enforcement Administration, which doesn’t allow them to prescribe Schedule I drugs. Even though it’s legal in Colorado, cannabis is still labeled a Schedule 1 drug federally.

A 2000 ruling by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that doctors in states with medical marijuana have the legal right to recommend marijuana but not prescribe it, and that’s what has Lasater and other doctors worried.

“I’m not willing to put my licenses on the line,” she says. “I’d be breaking the Colorado Medical Practice Act and Uniform Controlled Substances Act by prescribing the use of an illicit substance.”

Lasater isn’t alone in her concerns. Vibrant Health Clinic, a medical marijuana clinic in Colorado Springs, last month announced that it was closing after both of its doctors said they were unwilling to practice under HB 1317’s new rules. Dr. Robert Cohen, owner of Cohen Medical Centers, reports that one of his physicians resigned in January, as well.

Martha Montemayor, co-founder of Healthy Choices Unlimited, says that two of her three remaining doctors have joined a lawsuit filed against Governor Jared Polis, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, the Colorado Department of Revenue and that department’s Marijuana Enforcement Division over HB 1317’s implementation. She closed down her clinic for a week to learn how to comply with the new law, and she says she’s still unsure of the legislation’s long-term effects.

Montemayor’s doctors are currently filling in patient dosage and consumption requirements on forms required by HB 1317 with language referring back to the Colorado Constitution, which directs that medical marijuana use be up to the patient.

“Most of the doctors in our group right now are using language on patient certification that refers back to the constitution. This is a fine line we’re walking, because we’re using the constitution rather than the law in 1317, and that’s based on the fact that we believe this violates the state constitution,” Montemayor says.

Originally filed by nineteen-year-old epileptic patient Benjamin Wann, the lawsuit that Montemayor’s doctors joined claims that physicians are forced to violate language in the Colorado Constitution as well as other state laws in order to write marijuana prescriptions, and that Colorado’s new medical marijuana purchase tracking system violates patients’ right to privacy. Wann’s lawyers are currently seeking a preliminary injunction against HB 1317 in Denver District Court. The lead attorney, Alex Buscher, declined to comment on the case.

Despite their concerns, no Colorado doctors have lost their DEA or medical licenses because they’ve prescribed or recommended marijuana since January 1. In an email to Westword, DEA public information officer R. Steve Kotecki says that the agency “does not review individual states’ marijuana policies or comment on state legislation.” But he also points out that all forms of marijuana are still federally prohibited.

Dr. Eric Eisenbud, a physician for Cohen Medical and Relaxed Clarity clinics, says he doesn’t feel at risk for persecution by the feds, but takes exception to losing his ability to diagnose his patients, an ability no other licensed physicians have lost in Colorado. According to Eisenbud, a “considerable percentage” of his patients don’t have health insurance, which is why the lower prices and tax rates of medical marijuana play key roles in getting a medical card rather than buying recreational products.

“If you’re a new patient and are required to see a family-practice doctor to generate medical records, you have to find a doctor to pay that extra fee, which can be $150 to $200 without health insurance,” Eisenbud says. “Even with something that might be quite obvious, like multiple sclerosis, where someone has paralysis of the leg, a doctor can’t recommend cannabis alone.”

Figuring out dosage and the right medical marijuana product for new patients varies with the individuals and their ailments, according to medical marijuana physicians.

“Because there’s so much variability from patient to patient, when someone is starting to treat pain, they have to try certain products by themselves and do a systematic investigation,” Eisenbud explains. “Everyone reacts differently. It’s not like prescribing Valium to somebody, where you know what will happen and you know what the dosage is.”

Eisenbud says he believes that proponents of HB 1317 had good intentions in trying to protect children, but that lawmakers didn’t engage with the medical marijuana community enough before passing the bill. Nor did the CDPHE provide adequate guidance for doctors and patients after the bill passed, he adds.

The CDPHE, which is responsible for regulating Colorado’s medical marijuana program, sent a twenty-page letter to the Colorado Board of Health in December outlining doctors’ concerns regarding HB 1317. But according to a spokeswoman, the CDPHE doesn’t have any oversight of medical providers and can’t provide legal guidance to doctors.

“Throughout our Board of Health rulemaking stakeholder engagement process, we received stakeholder feedback that expressed many of the concerns you’ve listed. While we acknowledge the concerns, the registry is required to comply with the law and collect the information outlined in House Bill 21-1317. Although we are required to collect the information, we do not have any oversight of medical providers or medical practice and cannot provide legal guidance,” says Medical Marijuana Registry communications specialist Mariah LaRue, who then adds that the CDPHE can’t comment further on HB 1317 because of Wann’s ongoing lawsuit.

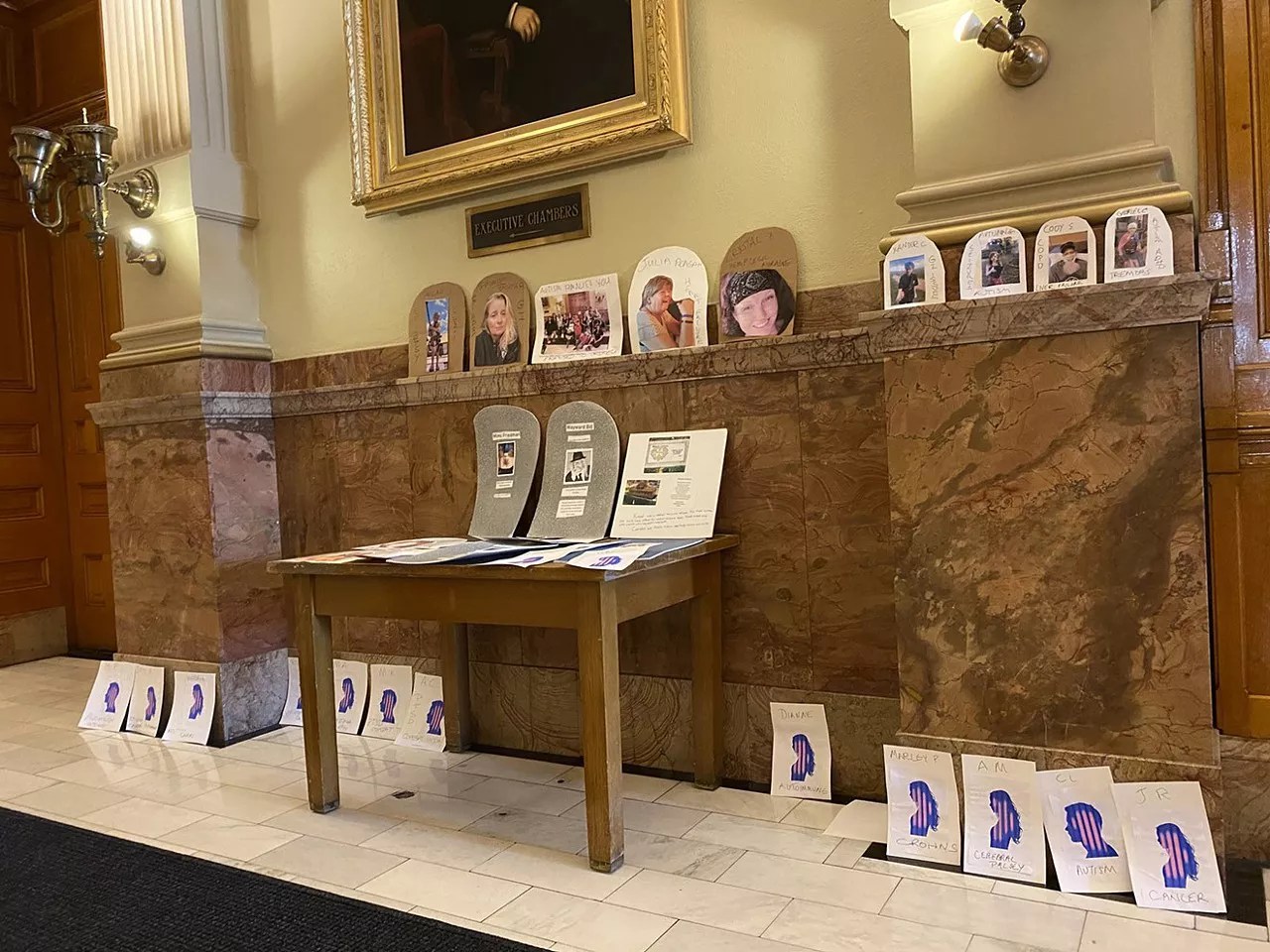

Medical marijuana patients left symbolic gravestones outside Jared Polis’s office to protest his signing of HB 1317.

Courtesy of Bridget Dandara-Seritt

Medical marijuana wasn’t the only product under fire. The battle over cannabis concentrate was brewing long before it became a focus of HB 1317.

Reports of proposed potency caps on the THC in regulated marijuana products had been leaking out of the Colorado Capitol for years before HB 1317 was introduced, and the first attempt in 2021 was much more aggressive than the version that ultimately passed. A draft by Representative Yadira Caraveo, a Democrat who’s a practicing pediatrician, that surfaced in February 2021 called for a 15 percent THC cap on all commercial pot products, and would have banned any form of certain infused products, such as medical marijuana suppositories and inhalers.

Colorado’s recreational cannabis industry, fresh off $1.75 billion in sales in 2020, immediately pushed back against the proposed legislation, but it soon became clear that the legislature wouldn’t end the session without new restrictions, according to Marijuana Industry Group Executive Director Truman Bradley.

Packaged as an attempt to curb youth use of extracted marijuana products, the official version of HB 1317 was introduced by House Speaker Alec Garnett and Caraveo. The bill, sponsored and championed by Democrats, received little opposition from legislators or the recreational marijuana industry – although the medical marijuana community protested the proposal right up until Polis signed it into law last June.

During discussion of the bill, proponents focused on the dangers of high-potency THC products, such as THC oil, wax, shatter, live resin and rosin, and their infiltration among Colorado teenagers.

Colorado health professionals had declared a state of emergency in youth mental health last year, listing marijuana use as one of several contributing factors. Although youth use of marijuana in the state has remained flat since recreational legalization, use of extracted marijuana products doubled from 2015 to 2019, according to the CDPHE. Most of these products are consumed by electronic and manual vaporization, also known as dabbing, and have been shown to impact developing brains in people 25 and under.

While recreational sales in Colorado are limited to those 21 and older, people between the ages of eighteen and twenty can apply for a medical marijuana card. Pointing to CDPHE data showing that there were around 4,000 patients in that age range and around 150 patients between eleven and seventeen, parents and health-care professionals told lawmakers that they were worried that patients under 21 were selling medical marijuana to children.

During public hearings on the bill and subsequent implementation meetings held by the MED, parents talked about how their children slowly became hooked on various forms of marijuana concentrate, which now ranges from 50 percent to upwards of 90 percent THC; some of those children had even attempted suicide, they said.

“It is still a drug. Over the years I’ve been a pediatrician in private practice, I’ve noticed more young people are using these products,” Caraveo said at a 2021 press conference, explaining that she wanted the state to start “treating medical marijuana more like any other medicine.”

Faced with a potency cap or the compromises of HB 1317’s rules and restrictions, the commercial pot lobby chose the latter.

“This is a tough one,” Bradley admits. “HB 1317 had a very aggressive implementation date, which was complicated by the holidays. I feel good that we were successful in increasing protection for kids, but patients need access.”

Dr. Peter Pryor left the emergency room to start a medical marijuana practice.

Thomas Mitchell

Bradley says he can understand why members of the medical marijuana community feel like they became collateral damage during the push to get HB 1317 through the legislature. And Brooks, Walker, Cohen and others definitely think they were scapegoated; lawmakers never engaged with them in good faith, they charge.

Part of the problem is that medical marijuana has become an increasingly smaller part of the state’s pot industry.

Since recreational sales began in Colorado on January 1, 2014, registered patient numbers have been on a slow decline, dropping from 111,020 to 86,460 by the end of 2021, according to CDPHE data. Despite the drop in patients, medical marijuana sales totals remained relatively constant, with users gravitating toward the stronger products, cheaper prices and lower taxes on the medical side. Still, commercial interest in medical has slowed significantly over the past seven years.

In 2014, there were 496 active medical marijuana dispensary licenses issued throughout Colorado, according to MED archives, compared to 142 recreational dispensary licenses. As of January 2022, there were 652 licenses for recreational stores and 420 for medical, while recreational growing operations now outnumber their medical counterparts 795 to 484.

Caregivers and the home-growing model have also fallen off since the state legislature and municipalities such as Denver and Pueblo passed laws restricting the amount of medical marijuana that could be grown for personal use. There were 3,174 registered caregivers in 2015, the first year the CDPHE began sharing such data. By the end of 2021, that number had dropped to 1,650.

Some local governments have also moved away from the medical marijuana industry altogether, with communities like Aurora, Broomfield, Fort Lupton, Grand Junction and Thornton opting in to recreational sales but not medical.

Jason Warf, director of the Southern Colorado Cannabis Council, doesn’t think that’s a coincidence. Warf, whose business members are mostly located in Colorado Springs (where only medical marijuana sales are allowed), says the recreational pot industry intentionally turned its back on medical patients in 2021.

“We have recreational businesses in our membership, too, and want to see everyone succeed, but the reality is that we had made an agreement industry-wide before the sessions started. We had wind that THC caps were coming, and we made a pact to oppose anything along those lines, period,” Warf says. “We have to put the blame back on ourselves. We have to find a way to be united next time, and we have to out the folks who don’t want to be part of that coalition.”

While Bradley doesn’t expect any more cannabis restrictions to be introduced in the legislature this year, Warf isn’t so sure: “We think 1317 was really just meant to lay the groundwork to circle back on,” he says.

Colorado Speaker of the House Alec Garnett was a big factor in passing HB 1317.

Jeffrey Beall/Wikipedia CC

As thanks for his work on HB 1317, Garnett was named Advocate of the Year by Smart Approaches to Marijuana (SAM), one of the country’s most prominent anti-marijuana legalization groups, which has called legalization “a public health nightmare.”

“It was a privilege to work alongside so many dedicated parents, educators and health-care providers to curb youth access to concentrates and advance critical research into how these high-potency products impact the developing brain,” Garnett says in a statement to Westword. “Too many young Coloradans have experienced devastating health impacts after consuming high-potency products. I’m proud of Colorado’s well-regulated and thriving marijuana industry, and I’m proud of how we are leading the way to learn more about high-potency products. The law we passed strikes a balance to protect access for patients and keep high-potency concentrates away from kids who shouldn’t have them.”

But concentrated cannabis products and dabbing aren’t usually a doctor’s first recommendation to a patient, according to Dr. Peter Pryor. He says he’d prefer that his patients medicate with edibles or oral cannabis medication, but he recognizes the immediate relief that smoking or dabbing can provide by entering the bloodstream faster.

Pryor says that the provisions of HB 1317 have pushed him between a state rock and a federal hard place. If he complies with the state, he worries he’s risking his medical and DEA licenses, but if he doesn’t follow the new rules, he believes he’s even more likely to face punishment. And if more medical marijuana doctors leave Colorado, his situation could become even tighter.

“A handful of new people are coming to me, saying their doctors’ offices are closed. It’s hard to know why all of these things are happening, but it seems frenetic and unsure from the top down,” Pryor adds.

A former emergency-room doctor, Pryor has been running his own medical marijuana practice, Doc Morrison, in Wheat Ridge since 2013. The new law has sidelined another Pryor priority: trying to legalize telemedicine for patient visits, another standard medical practice that marijuana doctors aren’t allowed to use in Colorado. As the state continues dealing with waves of COVID-19, he worries that Colorado’s medical marijuana program is going the wrong way for vulnerable patients, and has considered moving his practice to Montana.

“This has created all sorts of fear,” he says. “I’m at the point of doing what I think is best and writing what I think is best for my patient, whether it’s at risk of my license or not. The attitude feels like they’re trying to get rid of us. There’s definitely a different feeling in the air right now. That law has a lot of specific changes, all of which seem pretty threatening if you’re a medical marijuana doctor.”