There was once a guy with a guitar who popped an erection while playing songs about his feelings.

That singer-songwriter knew his way around a fretboard and wanted to make sure the few in the crowd knew he did, too. He plucked solo after solo, demonstrating his mastery — no matter how many people fled the shop, no matter how many eyelids drooped. His voice was well-trained but grating. He squinted as he sang, as if God burned in a bush behind those closed eyes. The longer he played, the harder he got. An hour later, still looking like he’d downed a bottle of Viagra, he stepped off stage, as unsatisfied as the handful of people avoiding eye contact with him.

He — along with the other thousands of sincere men with guitars and emotions — offers a prophetic vision of hell. And who’s to blame for this coffee-shop scourge?

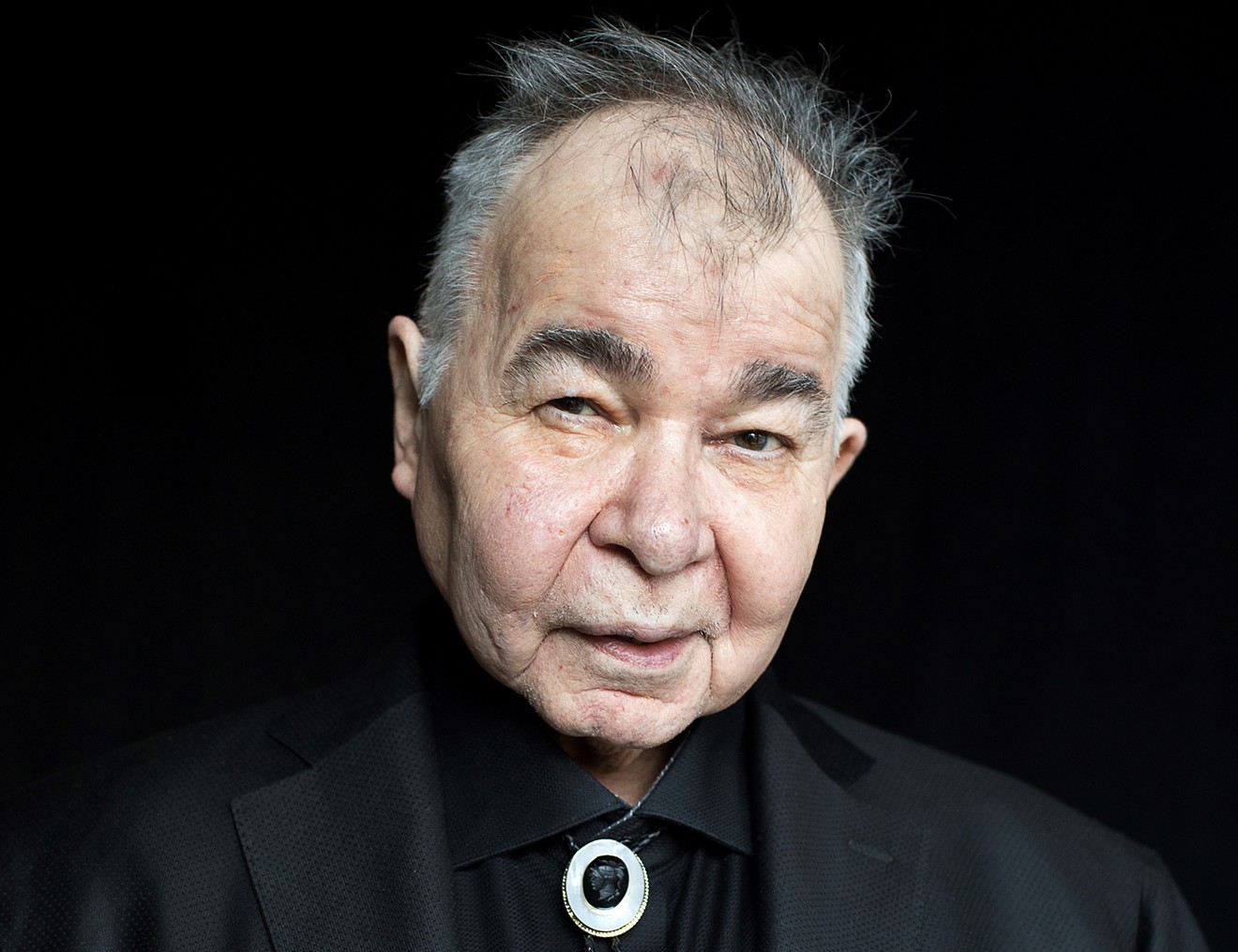

Maybe John Prine.

If you were at Red Rocks on Wednesday, September 18, as Prine made his way through nearly fifty years of songs, you’d understand what erect pickers aspire to.

Prine writes simple songs with quirky lyrics and catchy melodies. He’s a storyteller — Raymond Carver with a guitar — singing in a gravelly timbre that has only grown rougher and better after decades of cigarettes and surgeries. His voice whittles down whatever calluses we’ve built over our souls. He helps us find meaning in the moment we’re living in, no matter how banal.

“Just come on home,” he sang.

Our cheeks turned wet.

“Sam Stone was alone when he popped his last balloon.”

We held back sobs.

And when he wrapped with that story of a son asking his father to see paradise in Muhlenberg County and belted out the chorus, “Well, I’m sorry, my son, but you’re too late in asking/Mister Peabody’s coal train has hauled it away,” my nostrils flared. I grit my teeth. I cried angry tears. Political tears.

“You should have seen the woman next to me. She was blubbering with a Kleenex,” one man said after the show as he made his way back to the parking lot.

Prine croaked out classics like the devastating “Hello in There” that he’s been singing since his self-titled debut album dropped in 1971. He wooed the crowd with the dirty love song “In Spite of Ourselves,” which he sang with the night’s openers, the folk group I’m With Her. He also served up several songs off his 2018 album, The Tree of Forgiveness, including the hilarious “Egg & Daughter Nite, Lincoln Nebraska, 1967 (Crazy Bone)” and “When I Get to Heaven,” the cheeriest song about dying ever sung.

His fans, young and old alike, belted along louder to the new stuff than the old, showing that his songwriting’s as relevant as ever. And for an artist whose fame peaked forty years ago, that’s a rarity.

When he set up “Donald and Lydia,” he told the audience, “I sang this song the first time I ever got up on a little stage in Chicago.”

“What year was that?” a fan shouted out.

“It was 1803,” Prine mumbled, causing an uproar.

We knew we were lucky to be there, and not just because he had rescheduled his first Red Rocks date after learning he was on the verge of having a stroke. He knew he was lucky to be there, too. The women in I’m With Her waxed about what “a dream come true” it was to open for Prine, and their joy as they accompanied him radiated to the upper seats. Even Prine’s bandmates, who looked at him with love all night long, are lucky for every night they back him.

Had it been Prine, his band, Red Rocks and the fans, it would have been a perfect night. But the Colorado Symphony and conductor Christopher Dragon were also there.

No doubt, the orchestra is a Denver institution for good reason. The musicians are talented. Watching Dragon conduct is one of the city’s great pleasures. Teaming up with pop stars, rock bands and folksingers has been a lucrative move for the Colorado Symphony. And often, it's been a smash.

But Dragon and his orchestra risked stampeding the evening with jaunty Aaron Copland-inspired Americana, pumped up with emotionalism unbecoming of Prine’s subtly. Only once — when the harpist teed up the intro for “When I Get to Heaven” and others in the orchestra delivered the dramatic flourishes the song calls for — did the Colorado Symphony add to the night. Mostly, the mob of musicians just stroked their strings and blew their reeds in the background, aspiring to grandeur but nearly sabotaging what makes Prine's music singular: the bare bones.

A lesser artist would have been drowned out the whole night. Yet despite the tsunami of sentimentalism from the orchestra, Prine mostly stayed afloat. He even seemed to like it, and what artist wouldn’t feel honored having a city’s orchestra play behind him? He referred to the musicians and Dragon as “my new friends.” He set up big expectations for “Hello in There,” when he said, “I heard the symphony play this song last night, and it really killed me. So hang on to your handkerchiefs.” But the sound mix, which favored the orchestra Peter-and-the-Wolfing big feelings over Prine, swallowed him. His poignant lyrics sank beneath the swells of the strings, and for a few bars in that song, he was lost.

I don’t blame the Colorado Symphony for any of this. No orchestra could have done any better — especially with a sound engineer putting the strings on steroids. But even if the mix was on point, Prine’s three-chord song structures don’t lend themselves to what an orchestra’s good at doing: playing big, broad, complicated scores, with surprising dynamics, feuding melodic lines and sweeping, evolving chords.

If anything, the Colorado Symphony’s tedious arrangements, rife with arpeggios on repeat, showed why so few folk artists use orchestral backing and why so few orchestras take on folk: It just doesn’t work. The contrast isn’t an artful revelation; it’s clunky.

Unwittingly, the contrast highlighted the ragged complexity of Prine and his band, surprising in timbre and pitch, despite their limited melodic and chordal variation. And when the orchestra players rested their instruments or bowed out, it only made Prine and his band that much better.

Sure, he brought his flaws. But he knows how to turn those into charms. At one point, he stopped a song to cough. “I have one of them sand bugs down in my throat,” he said. And at times, alone on the stage, his frets buzzed, giving his picking a clumsy quality that he played right through. But that just made us feel like we were around a campfire with friends.

“I hope you’re enjoying yourselves, because we’re having a ball,” he told us mid-set. Of course we were. But he gave us something more: Prine gave us his peace.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "12017618",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261320",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17261321",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]