Audio By Carbonatix

A new report by student attorneys with the Civil Rights Clinic associated with the University of Denver’s Sturm College of Law paints a horrific picture of the protective-custody unit at the Buena Vista Correctional Facility, a Chaffee County complex overseen by the Colorado Department of Corrections. The unit is occupied by inmates, including those who identify as LGBTQIA+, most at danger of mistreatment and worse from fellow prisoners.

“Abused and Forgotten: Life Inside the BVCF Protective Custody Hallway,” released August 3, describes the module as “a terrifying and abysmal place for most of the people housed there. And it is well known in CDOC that if a person is forced to enter protective custody – for example, by becoming a target as a result of refusing their gang’s order to hurt a staff member – they will likely end up serving their sentence in the miserable hallway.”

“There’s nothing that gives you hope,” notes an inmate quoted by authors Sam Battey, Kate Rosner and G.C. “It’s Groundhog Day, a horrible version of Groundhog Day.”

CDOC spokesperson Annie Skinner rejects such characterizations. “While our department is always looking for ways to improve our outcomes, we deeply disagree with the narrative created by the authors of this report,” she states. But Laura Rovner, a DU professor and director of the Civil Rights Clinic, who oversaw the project, defends the findings, which contend that a facility intended to protect vulnerable inmates consistently restricts their ability to benefit from programs that can decrease their time behind bars while failing to prevent them from becoming victims of violence.

“One of the people we spoke to said, ‘My only options are to stay in protective custody and never get paroled or take sex-offender treatment in the general population and risk being assaulted,'” Rover notes. “And we also heard things like, ‘The cops used to ask me why I didn’t get away from gang life. And when I do, I get treated worse.'”

The Buena Vista Correctional Facility is part of the Buena Vista Correctional Complex, located at 15125 U.S. 24 in Buena Vista, a town in Chaffee County.

According to Rovner, the Civil Rights Clinic’s work “generally focuses on constitutional issues for people in prison, and a couple of years ago, we started getting a lot of complaints about the protective-custody unit at Buena Vista. We heard over and over again about dangerous conditions that were really degrading, and that there was no way of notifying people during emergencies. So we started looking into it in more depth, which was challenging, because our research coincided with COVID. But we did some open-records requests and corresponded with people who were or are in the unit, and we discovered some really troubling things.”

Protective-custody units were already on Rovner’s radar. By the 1990s, she says, most correctional systems at both state and federal levels had created such spaces “to house people who are especially vulnerable to prison violence – people who may have aided the government, gang members who’ve renounced their membership, people who’ve committed certain crimes that make them targets, people in the LGBTQIA+ community or people who are at high risk because of their physical characteristics.”

Colorado didn’t launch its first protective-custody unit until 2013, however, and even today, there are still only two in the state, the one at Buena Vista andone at the Arkansas Valley Correctional Facility in the Crowley County community of Ordway. While the Arkansas Valley protective-custody unit provides “programming that’s required for parole, including sex-offender treatment and drug-and-alcohol treatment,” Rovner says, the report reveals that that’s not the case at the Buena Vista unit – though it is available in the rest of the prison. As a result, “people who are classified as needing protective custody at Buena Vista are serving longer sentences, in some instances,” she adds.

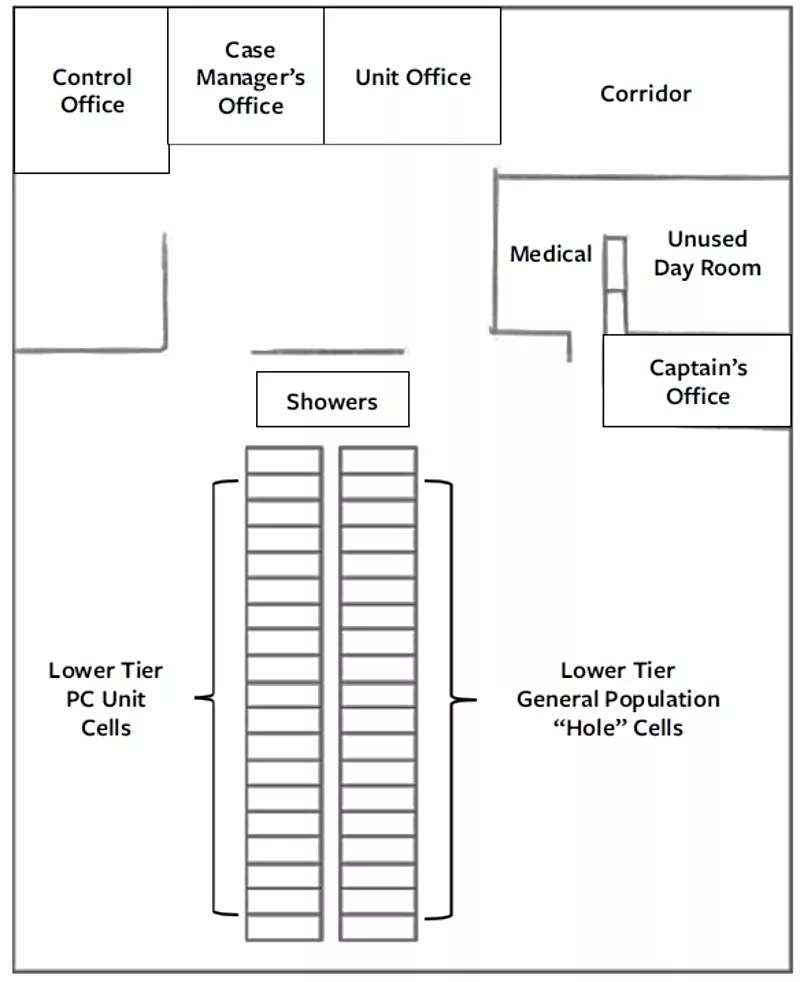

Another major theme of the report involves the section of the prison devoted to protective custody. “It used to be a disciplinary-segregation unit, and it has a layout typical of disciplinary-seg,” Rovner says. “There are these kind of box-car cells that are next to each other and all face out into the hallway – and that’s the entire unit. Normally, there’s a day hall, where people can go and gather. But this unit wasn’t envisioned as a place where people were going to be out of their cells for long periods of time, and a bunch of things flow from that.”

For one thing, she continues, “people don’t have any way to notify staff if someone is having an emergency; we heard about that from people who had seizures and a person who has diabetes and is insulin-dependent. And when there’s violence, there’s no way to let people know when they’re locked in their cells – no emergency-call buttons like there are in other prisons to let staff know that’s happening. People are literally banging on their cell doors, these solid-steel doors, to get the attention of staff, who are located at the end of this long, narrow hallway, for some reason. So it may take hours for them to be noticed, which is an incredibly dangerous situation that’s just waiting to have a bad outcome.”

The floor plan of the Buena Vista Correctional Facility protective-custody unit.

The problematic floor plan and the lack of programming opportunities, including vocational training, combine to create another problem. “People told us that because there’s nothing to do, there’s frequent physical violence that they attributed to boredom, frankly, and these incredibly cramped quarters,” Rovner points out. “People are only allowed out of their cells for a few hours a day, and there’s really nowhere to go, because you’re just in this hallway narrow enough to touch each side if your arms are outstretched. So either they play cards or they make hooch, prison wine – and that can lead to even more incidents, with no ability to let staff know if someone has been hurt.”

Such scenarios are even more concerning, Rovner believes, because “much of the physical violence in the unit goes unaddressed, and the staff has been verbally and sometimes physically abusive to people forced to live there. I don’t want to paint with too broad a brush, but there are a couple members of the staff who seem keenly aware that they have the ability to kick somebody out of protective custody – and if that happens, these people know they’re in real danger. We heard about situations where staffers have said someone is a child molester in front of other people in the unit, which is an incredibly dangerous thing to say within earshot of other incarcerated people. And there was another instance of a man who ended up getting pepper-sprayed, which triggered a mental health disorder – but instead of decontaminating him in a cold shower, which is what you’re supposed to do, they put him in a hot shower, which amplifies the effect of the pepper spray, and left him there.”

The report’s recommendations include “relocating protective custody to someone else in the facility, so that it doesn’t become a punitive experience for people who need it,” Rovner says. “We also ask that sex-offender treatment and drug-and-alcohol treatment be offered in all protective-custody units, and that specialized training be conducted for staff, since it’s incredibly important that they’re aware of the issues people in there are facing. And we’ve also called on the Department of Corrections’ inspector general to conduct a full investigation of the unit, so they can go even deeper than we were able to do.”

CDOC’s Skinner doesn’t address these specific suggestions, but does criticize how the report was released. “We are disappointed that despite the department’s efforts to make meaningful changes in collaboration with the clinic, they chose to issue a document without providing us the opportunity to comment or contribute factual information before publication,” she says.

Rovner pushes back on this assertion. She says the report team reached out to CDOC director Dean Williams in March 2021 to request a meeting to discuss concerns over the Buena Vista unit. When her group arrived for the scheduled sit-down on April 5, Williams was unavailable, but they shared information with numerous other department administrators and a representative from the Colorado Attorney General’s Office. Three follow-up efforts, on April 8, April 22 and April 30, yielded no results, and neither did an attempt to huddle again with Colorado Attorney General’s Office personnel in May, she says.

“Our invitation to CDOC officials to join us in a meeting with people incarcerated in the BVCF PC Unit is still outstanding,” Rovner stresses. “We remain available for such a meeting if CDOC is interested.”

She adds: “The report is the product of hundreds of hours of careful, painstaking work by Civil Rights Clinic student attorneys, who conducted interviews and corresponded with over forty people currently or formerly incarcerated in the BVCF PC unit, reviewed documents obtained from CDOC via open-records requests, and considered publicly filed documents in litigation involving protective custody in CDOC. We stand by the report, including its conclusions and recommendations.”

Click to read “Abused and Forgotten: Life Inside the BVCF Protective Custody Hallway.”